Experiences of “Being Known” by the Healthcare Team of Young Adult Patients With Cancer

Purpose/Objectives: To explore how young adult patients with cancer experience “being known” by their healthcare team.

Research Approach: Qualitative, descriptive.

Setting: A university-affiliated hospital in Montreal, Quebec.

Participants: 13 patients with cancer aged 18–39 years.

Methodologic Approach: Semistructured interviews were conducted and analyzed using thematic content analysis.

Findings: Living with cancer and being labeled as a young adult were described, and participants reported being known in relation to two themes: being treated as “not a number” and being a patient within a culture of care.

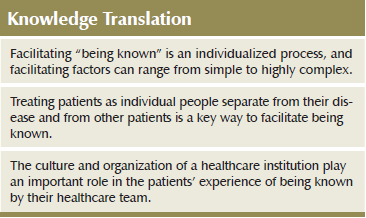

Conclusions: Being known was highly valued and was experienced and expressed in a unique way for each individual. However, the process often occurred from simple interventions related to the healthcare provider or the setting itself.

Interpretation: Although no standardized tools can be used to facilitate being known, the current study sheds light on how being known may be achieved and can be helpful in meeting the needs of young adult patients with cancer.

Jump to a section

Adolescents and young adults (AYAs) increasingly have been recognized as a subpopulation of patients with cancer who have been largely understudied and under-represented within the research community (Bleyer, 2007; Evan & Zeltzer, 2006; Fernandez et al., 2011; Haase & Phillips, 2004; Morgan, Davies, Palmer, & Plaster, 2010; Zebrack, Bleyer, Albritton, Medearis, & Tang, 2006; Zebrack, Mills, & Weitzman, 2007). Although the incidence of cancer within this age group is lower than in older adults, implications of the illness have been found to have a greater effect than in other oncology populations (David, Williamson, & Owen Tilsley, 2012; Fernandez et al., 2011; Zebrack, Chesler, & Kaplan, 2010).

Literature Review

Defining the Adolescent and Young Adult Population

No clear distinction between the “adolescent” and “young adult” age brackets is made within the reviewed literature, although significant differences in developmental tasks and healthcare concerns have been identified (Friedman, Bowden, & Jones, 2003). Broad definitions of the term AYA exist within the literature, ranging in age from 15–44 years (Bleyer, 2007; D’Agostino, Penney, & Zebrack, 2011; Fernandez et al., 2011; Zebrack et al., 2006). Because of the differences between adolescents and young adults within the AYA subpopulation, the current study focused solely on the experiences of young adults aged from 18–39 years within the adult cancer care system.

Young adulthood is recognized as a time of great transition. Normative developmental tasks include developing autonomy, entering the workforce, exploring sexuality and fertility, and creating a personal identity with a strong reliance on peers for support and a sense of belonging (Bleyer, 2007; D’Agostino et al., 2011; Morgan et al., 2010; Zebrack et al., 2007). Several studies have identified the unique psychosocial needs of AYA patients with cancer (Bleyer, 2007; D’Agostino et al., 2011; David et al., 2012; Evan & Zeltzer, 2006; Fernandez et al., 2011; Haase & Phillips, 2004; Kyngäs et al., 2001; Morgan et al., 2010; Zebrack et al., 2006, 2007, 2010), which include an individualized model of care and a greater sense of continuity throughout their cancer care trajectory (Bleyer, 2007; D’Agostino et al., 2011; David et al., 2012; Fernandez et al., 2011; Haase & Phillips, 2004; Kyngäs et al., 2001; Zebrack et al., 2007, 2010).

As defined for the general population of patients with cancer, individualized care occurs when the nurse knows the patient as a unique individual and tailors care to the patient’s experiences, behaviors, feelings, and perceptions (Radwin & Alster, 2002). Studies within the AYA population have identified the importance of this concept, which includes such notions as flexibility to provide for individual needs (Zebrack et al., 2006) and information tailored to fit medical and psychosocial needs specific to this population (D’Agostino et al., 2011). Studies also have identified certain helpful healthcare provider characteristics: knowing the patient as an individual; recognizing particular needs; showing a personal interest; and being compassionate, attentive, nonjudgmental, and able to establish a strong human connection (Luker, Austin, Caress, & Hallett, 2000; Plante & Joannette, 2009; Radwin, 2000; Thorne et al., 2010; Wilkinson, 1991; Zebrack et al., 2010).

Continuity of care has been identified as an important approach to addressing the many psychosocial needs expressed by the AYA population (Kyngäs et al., 2001; Morgan et al., 2010) and other populations (Dumont, Dumont, & Turgeon, 2005; Fillion et al., 2009; Luker et al., 2000; Radwin, 2000; Thygesen, Pedersen, Kragstrup, Wagner, & Mogensen, 2011; Whittemore, 2000). Defined as “the degree to which a series of discrete healthcare events is experienced as coherent, connected, and consistent with the patient’s medical needs and personal context” (Fillion et al., 2009, p. 213), continuity of care has been linked with better emotional functioning (Fillion et al., 2009) and positive patient–healthcare provider communication (Dumont et al., 2005; Fillion et al., 2009; Radwin, 2000; Thygesen et al., 2011; Whittemore, 2000). A literature review on continuity of care (Dumont et al., 2005) identified three main dimensions: informational, management, and relational. Many authors have found the relational aspect to be of particular importance (Dumont et al., 2005; Fillion et al., 2009; Luker et al., 2000; Phillips-Salimi, Haase, & Kooken, 2012; Radwin, 1996, 2000; Radwin & Alster, 2002). Providing patients with the opportunity to develop relationships with their healthcare providers can promote better communication, thereby increasing patient satisfaction and well-being (Bakker, Fitch, Gray, Reed, & Bennett, 2001; Carroll et al., 2010; Fillion et al., 2009; Luker et al., 2000; Radwin, 2000).

Being Known in the Adolescent and Young Adult Population

One of the most salient aspects of the human connection within individualized care and continuity of care has come to be understood as the concept of being known (Carroll et al., 2010; Luker et al., 2000; Radwin, 1996, 2000; Radwin & Alster, 2002; Suhonen, Valimaki, & Leino-Kilpi, 2009; Takemura & Kanda, 2003; Thorne et al., 2005; Thygesen et al., 2011; Whittemore, 2000). In a pivotal study by Thorne et al. (2005), being known was described as a sense of connection distinct from the physical disease that helped to define a patient as a unique human being. This connection included individual preferences, knowledge, intuitions, emotional needs, beliefs, and values, all of which were considered within a context of the person’s intrinsic worth. Because being known reflects a patient’s particular personhood, it was described in different ways by participants (Thorne et al., 2005). The difference in participant ages—ranging from younger than 30 years to older than 70 years—may have contributed to the considerable variation in findings. In addition, participants aged 18–39 years represented only 5% of the study sample, leaving a large gap in the understanding of this age group’s experiences of being known. By focusing on the specific age range of 18–39 years, the researchers in the current study hope to shed light on the experiences of members of the AYA population and what being known means to them.

Exploring being known, via concepts such as continuity of care and individualized care, may allow the needs of AYA patients to be better understood. Such needs include feeling visible (D’Agostino et al., 2011; Haase & Phillips, 2004), having a sense of connectedness with healthcare providers (Fernandez et al., 2011; Haase & Phillips, 2004; Zebrack et al., 2007, 2010), relating to their individual personalities and developing identities (D’Agostino et al., 2011; David et al., 2012; Fernandez et al., 2011; Morgan et al., 2010; Zebrack et al., 2007, 2010), and being understood and not judged for their decisions (Morgan et al., 2010; Zebrack et al., 2010). Therefore, for young adults undergoing treatment for cancer, being known by their healthcare team may help provide for their unique needs. The purpose of the current study is to explore how young adults with cancer experience being known by their healthcare team.

Methods

A qualitative, descriptive design with semistructured interviews was used, allowing for data to be explored in great scope and depth while taking a holistic approach (Polit & Beck, 2008). This design method is well suited to answering questions about approaches to care (Magilvy & Thomas, 2009). Inclusion criteria were being aged 18–39 years, undergoing treatment, and able to understand and speak English or French. Participants who declined to be audio recorded were excluded.

The current study was conducted at the Jewish General Hospital, a tertiary care, university-affiliated teaching hospital, in Montreal, Quebec. Convenience sampling (Polit & Beck, 2008) was used initially by recruiting patients from various cancer outpatient clinics in the hospital study site. Participants were approached by a trained member of the hospital staff in the clinic setting and given the opportunity to contact one of the researchers if interested in participating. Many of the initial participants recruited shared a diagnosis of hematologic cancer. Because the researchers were approaching data saturation, purposive sampling was used to round out the final sample and include a better representation of diagnoses within the age group. One-time, face-to-face, semistructured interviews were conducted by two separate researchers after training was completed and the development of similar interview style was established (see Figure 1). The interviews lasted about 30–60 minutes each, took place at the location of the participant’s choosing (i.e., a private room at the hospital or the participant’s home), and were audio recorded and transcribed, verbatim, within one week. Field notes recording verbal and nonverbal behaviors (Marrow, 1996; Polit & Beck, 2008) were written during interviews and as soon as possible after the interview.

Thematic content analysis was used because it details and systematically records themes and issues identified in interviews (Burnard, 1991). Each interview was coded and analyzed before the next interview was conducted. Common data were grouped into categories, which were distilled and analyzed for patterns and themes, and relationships between themes were considered (Polit & Beck, 2008). Data saturation was reached when no new data categories were identified during analysis of the interviews. An audit trail was kept, and investigator triangulation was used to enhance the confirmability of the researchers’ findings, as well as to ensure the dependability of the study over time (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Salient points, as interpreted by various research team members, were compared and discussed, and member checking was performed on a regular basis to reduce the risk of biased interpretation of data (Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

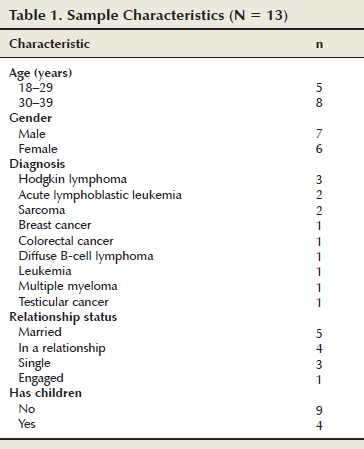

Ethical approval was granted by the Jewish General Hospital Research Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection. The current study’s population consisted of 13 participants aged 18–39 years. Participants were being followed in various stages of treatment or remission (see Table 1).

Findings

Cancer in Young Adulthood

A number of participants spoke directly about how being a young adult affected their experiences with their healthcare team, and they identified strongly with the young adult subpopulation. One participant said, “I just don’t feel that we are necessarily in the same situation [as other patients with cancer]. I mean, it’s the same sickness, but it’s not the same social context.” This group of participants used and appreciated specialized young adult patient services, such as support groups.

For some, individual factors played a more important role in their experience of cancer, and they did not identify with the young adult age group. One participant said, “I was ‘fitted’ in the young adults category, but didn’t really feel like I belonged.” This group described their experiences of being known more as patients in general and less as young adults.

One subgroup with a distinctly different perspective was comprised of patients who had children. They described how their cancer diagnosis and treatment took on a greater meaning within the context of being a parent to young children. “You’re fighting for your kids, and for yourself, but I mean, basically more for them than for you . . . and everything else loses in importance.”

Not a Number

A key aspect of care that facilitated participants being known was feeling as though they were “not a number”—being treated like a unique individual within the patient population and being recognized as a person separate from the disease. The components of this type of interpersonal care included being genuine, providing a sense of comfort, providing individualized communication, and including the patient as part of the team. This was emphasized by nearly every participant, and, as one participant expressed, “You’re not only a number, you’re someone.”

This component involved feeling that healthcare providers were not just performing the tasks required by their job but that they really cared and connected with the patient on a human level. One participant said, “It makes you feel like she’s not just giving you a treatment. She’s here and she cares about you.”

One participant highlighted his nurse’s ability to “just be there [for them], whether it’s in silence, or in conversations.” This was described further as always taking time to answer questions, actively listening, and never rushing appointments. Genuinely acknowledging the impact that cancer had on each individual situation also was integral to feeling known.

[Cancer is] a big event in our lives and they realize it, so it helps a lot. . . . Even if they see a lot of people, they’re concerned for every one of them. And, they really want you to be better.

This component occurred when healthcare providers were welcoming and friendly, smiled, and had casual conversations with patients. One participant said, “You have to be comfortable with your team, otherwise you’ll be lost.” This promoted the development of individualized relationships that led participants to feeling known by their team.

Basics, such as providing information in an understandable way, repeating when needed, and using direct and honest communication, were appreciated by many participants. One participant said, “She doesn’t go around the block to tell what’s going on. She’s straight up about it.” Tailoring information to each individual, by normalizing symptoms or addressing specific concerns, was important to feeling known. One participant said, “Not necessarily explain to me what’s about to happen, but, you know, feel what I need to hear and say it.”

Participants found healthcare providers recognizing their desire to stay positive and communicating in a way that fostered this helpful. One participant described the discussion of his initial diagnosis. “It was a serious, serious discussion but at the same time it was . . . a good discussion. When we left the office nobody was crying, everybody was happy.”

Another participant described how the use of humor lightened the atmosphere during a difficult procedure. “They always knew what to say to make you feel better.”

Participants feeling that they were a valued and integral part of their healthcare team was important. One participant said, “Even if I’m a patient, I’m a part of the team who fight[s] against my cancer.”

Collaborating with patients in decision-making and encouraging them to express concerns and ask questions facilitated this, as well as making exceptions or modifying care to meet specific needs. Collaboration with participants’ family and friends also was valued. One participant said, “There is an impact . . . not just on you, but on the . . . network of family and friends.” Another participant highlighted his wife’s role.

When you’re living together and you have kids together you’re almost getting to be the same person . . . If my spouse, my wife, is stronger she will be in a better mood to help me, encourage me, to support me.

Culture of Care

Participants also described several components that fostered becoming known by their healthcare team that could be attributed to the setting’s culture of care—the organizational attitudes and behaviors that reflect the approach to care.

Several participants remarked on the friendliness of the staff, which contributed to the overall positive atmosphere of the setting. “I’m sure in some places some people might be cold, but over here, I didn’t see anyone who was cold or not in a good mood. They’re always smiling.”

For some participants, the positive environment had deeper effects on their own mentality in the face of cancer. “I think one thing that makes me accept better what I have is that I’m very positive about it, you know. So I guess it’s encouraging when people around you have that spirit also.”

Having confidence in the competency of the staff enabled trusting relationships to develop with healthcare providers, laying the foundation for participants to feel known. “It’s like I can give myself for real into their hands and I’m fine. . . . There’s nothing I worry about because I can trust them.”

The concept of competency was important because patients wanted to feel that they were receiving the best possible treatment in a timely manner and that the team members knew what they were doing. Trust also was fostered by knowing that the team was working together. “It seems like they all have a good relationship with each other . . . because we’re all going in only one direction.” Another participant said, “They want to help each other, so by doing that, they help us even more.”

This component often was described as providing contact information, promptly returning phone calls, and being available for questions. “I knew she was always there for me. Like from the start, this is my number, this is where you call at night if anything happens. . . . That was helpful.”

The impact of not being accessible also was described. “One night the nurse said, ‘Okay, I’m going to come back later on,’ and she just never showed up. And I was calling and no one was coming . . . and yeah, you feel alone.”

Many participants discussed how seeing the same people over time helped with staying up to date on their case, remembering details, and following up with concerns.

Having one with whom you’ve shared all your experiences from day one to the last day really makes it easier because as soon as you have a problem they really know your case more than anybody else. So instead of sharing all your problems to different people, you have one specific person to whom you can go and talk to and to have more of a personal relationship.

When healthcare workers did not follow up or remember the patient’s case despite several meetings, the impact was undeniable. “You’re like waiting there for your . . . to know what’s going on with your life and they don’t even know why you’re here.”

Transferring information between professionals provided a sense of seamlessness in care. Several participants mentioned that when team members went on vacation, others easily took over their responsibilities. “The people that took over at the time [said], ‘I’m taking over, I know about this, I know about your file.’ So it felt nice.”

Discussion

Overall, participants described being satisfied with how well known they felt by their healthcare team, although this was experienced in different ways. Being known was clearly facilitated by two main elements: being treated like more than a number, and the culture of care that existed at the hospital. Although few previous studies have touched on the importance of a culture of care in facilitating being known, many have focused on the importance of being treated like an individual.

The researchers’ findings related to the importance of not being just a number are consistent with findings of previous studies on being known (Radwin, 1996; Thorne et al., 2005). Within the current study, many participants felt that they were treated like more than just a number; instead, they felt that they were seen as a person—distinct from their disease and from other patients. This concept of a human connection was central to the definition of being known in Thorne et al. (2005). However, Thorne et al. (2005) focused primarily on the importance of individualized communication in facilitating this connection. In Thorne et al. (2005), individualized communication took on a broader meaning, which included some aspects of care that were found to be important in the current study, such as being genuine. Although the current study sheds light on some of the nuances of holistic cancer care, it further illustrates the point that such care cannot be based on a standardized set of communication skills.

The important similarities that exist between the current study of young adult patients with cancer and other studies on being known in different and diverse populations were surprising. This age group has been represented in the literature as having unique medical and psychosocial needs (Bleyer, 2007; D’Agostino et al., 2011; David et al., 2012). However, the importance that young adults place on being treated as more than a number is consistent with previous studies in varied age groups (Radwin, 1996; Radwin & Alster, 2002).

One subgroup of participants within the current study who expressed common feelings was the patients with children, who felt they were fighting for their children as much as for themselves. Although being a parent to young children adding to the needs of patients is recognized, little is known about the ways in which healthcare providers can work with this population (Rauch, Muriel, & Cassem, 2002; Semple & McCance, 2010). Targeting this subgroup of the AYA population perhaps would elicit different experiences of coming to feel known by the healthcare team.

Although the researchers’ findings support the importance of providing tailored care, the impact of the culture of care in facilitating being known also was valuable to participants. Previous studies on being known have focused solely on the importance of the interpersonal relationship between patients and healthcare providers (Luker et al., 2000; Radwin, 1996; Thorne et al., 2005), and some studies have found that a close relationship is important to allowing nurses to learn about their patients (Luker et al., 2000; Radwin, 1996). In addition, Thorne et al. (2005) found that a technical orientation to the encounter between patient and healthcare provider was, in fact, seen as a barrier to the patient feeling known. In the current study, however, some participants expressed that a more professional relationship with a competent healthcare team was greatly important. The emphasis that patients place on their instrumental needs and the clinical expertise of their team has been well described by other studies and is consistent with the researchers’ findings (Bundgaard, Nielsen, Delmar, & Sorensen, 2012; Carroll et al., 2010; Fernandez et al., 2011). Therefore, the findings of the current study suggest that clinical competence and the culture of care of a setting play an important role in facilitating being known.

In the current study, patients felt that their team was competent when they knew the best clinical decisions were being made on their behalf, taking into account their specific wishes. This finding is consistent with a study by Liashenko (1997) that outlined the importance of knowing the case, the patient, and the person in order to make clinical decisions. When all three dimensions were well known, patients felt that a more effective relationship existed with their team (Liashenko, 1997). Liashenko’s (1997) findings suggest that the presence of being treated like more than just a number and a positive culture of care (e.g., competency of staff) could help strengthen the experience of being known.

Limitations

Limitations of the current study include the over-representation of participants diagnosed with a hematologic cancer. Recruitment was initially through convenience sampling and, despite the later use of purposive sampling to balance the distribution of diagnoses, a greater number of participants with hematologic cancers appear to be included in the researchers’ sample.

Many of the participants in the current study were assigned an infirmière pivot en oncologie (IPO), or oncology pivot nurse. IPOs, common in Quebec, play a central role in caring for patients and families (e.g., preventing and managing symptoms, developing individualized care plans, empowering patients and families) (Gilbert et al., 2011; Kavanagh & Loutfi, 2006; Plante & Joannette, 2009). Because of the nature of the IPO role and the overall satisfaction with being known expressed by participants, this satisfaction may be partially related to the continuity of care provided by the IPOs. The study findings may, therefore, not be generalizable to other settings in which the IPO role is not defined in the same way.

Implications for Nursing

Although defining the conditions that promote being known is complex, the findings of the current study do not point to being known as a necessarily complex process. Facilitating factors ranged from the very simple (e.g., remembering a participant’s name or diagnosis) to the more intricate (e.g., feeling that healthcare providers were like family members). This is consistent with previous studies, in which knowing the patient was found to be experienced uniquely by each person, and that no single behavior or pattern of behaviors was attributable (Radwin, 1996; Thorne et al., 2005).

Although many of the participants strongly identified with being a young adult, several did not feel it was a good fit. The age range was too wide, and some found identifying with participants on the older end of the spectrum difficult. Others felt too old to be considered a young adult. These findings suggest that the AYA grouping is based solely on age rather than actual commonalities. This could have clinical implications because grouping patients who fall into this wide age range in clinical settings and psychosocial support groups is common (D’Agostino et al., 2011; David et al., 2012; Evan & Zeltzer, 2006).

Along with the emphasis on interpersonal aspects of care, the cultural or organizational components had a strong influence on how patients can feel known. In the current study, participants provided examples of what that can look like.

Conclusion

The current study highlights the importance of being known and sheds light on the unique nature of the dynamics between healthcare providers and their patients. Although no standardized set of interventions exits that can be applied to facilitate being known, doing so does not need to be a complex process. Nurses can play an integral role in providing care and developing a culture of care that fosters being known without changing the fundamental philosophies already at the heart of nursing care.

References

Bakker, D.A., Fitch, M.I., Gray, R., Reed, E., & Bennett, J. (2001). Patient-health care provider communication during chemotherapy treatment: The perspectives of women with breast cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 43, 61–71.

Bleyer, A. (2007). Young adult oncology: The patients and their survival challenges. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 57, 242–255.

Bundgaard, K., Nielsen, K.B., Delmar, C., & Sorensen, E.E. (2012). What to know and how to get to know? A fieldwork study outlining the understanding of knowing the patient in facilities for short-term stay. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68, 2280–2288.

Burnard, P. (1991). A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Education Today, 11, 461–466.

Carroll, J.K., Humiston, S.G., Meldrum, S.C., Salamone, C.M., Jean-Pierre, P., Epstein, R.M., & Fiscella, K. (2010). Patients’ experiences with navigation for cancer care. Patient Education and Counseling, 80, 241–247. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.024

D’Agostino, N.M., Penney, A., & Zebrack, B. (2011). Providing developmentally appropriate psychosocial care to adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer, 117, 2329–2334.

David, C.L., Williamson, K., & Owen Tilsley, D.W. (2012). A small scale, qualitative focus group to investigate the psychosocial support needs of teenage young adult cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy in Wales. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 375–379. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2011.08.002

Dumont, I., Dumont, S., & Turgeon, J. (2005). Continuity of care for advanced cancer patients. Journal of Palliative Care, 21, 49–56.

Evan, E.E., & Zeltzer, L.K. (2006). Psychosocial dimensions of cancer in adolescents and young adults. Cancer, 107, 1663–1671.

Fernandez, C., Fraser, G.A.M., Freeman, C., Grunfeld, E., Gupta, A., Mery, L.S., . . . Schacter, B. (2011). Principles and recommendations for the provision of healthcare in Canada to adolescent and young adult-aged cancer patients and survivors. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 1, 53–59. doi:10.1089/jayao.2010.0008

Fillion, L., de Serres, M., Cook, S., Goupil, R.L., Bairati, I., & Doll, R. (2009). Professional patient navigation in head and neck cancer. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 25, 212–221. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2009.05.004

Friedman, M.R., Bowden, V.R., & Jones, E.G. (2003). Family developmental theory. Family nursing: Research, theory, and practice (5th ed.)(pp. 103–144). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Gilbert, J.E., Green, E., Lankshear, S., Hughes, E., Burkoski, V., & Sawka, C. (2011). Nurses as patient navigators in cancer diagnosis: Review, consultation and model design. European Journal of Cancer Care, 20, 228–236. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2010.01231.x

Haase, J.E., & Phillips, C.R. (2004). The adolescent/young adult experience. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 21, 145–149.

Kavanagh, M., & Loutfi, A. (2006). La governe de la lutte contre le cancer au Quebec. Bulletin du Cancer, 93, 835–836.

Kyngäs, H., Mikkonen, R., Nousiainen, E.M., Rytilahti, M., Seppänen, P., Vaattovaara, R., & Jämsä, T. (2001). Coping with the onset of cancer: Coping strategies and resources of young people with cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 10, 6–11.

Liashenko, J. (1997). Knowing the patient? In S.E. Thorne & V.E. Hayes (Eds.), Nursing praxis: Knowledge and action (pp. 23–37). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lincoln, Y., & Guba, E.G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Luker, K.A., Austin, L., Caress, A., & Hallett, C.E. (2000). The importance of ‘knowing the patient’: Community nurses’ constructions of quality in providing palliative care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 31, 775–782. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01364.x

Magilvy, J.K., & Thomas, E. (2009). A first qualitative project: Qualitative descriptive design for novice researchers. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 14, 298–300. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6155.2009.00212.x

Marrow, C. (1996). Using qualitative research methods in nursing. Nursing Standard, 11(7), 43–45. doi:10.7748/ns1996.11.11.7.43.c2478

Morgan, S., Davies, S., Palmer, S., & Plaster, M. (2010). Sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll: Caring for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 4825–4830. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.22.5474

Phillips-Salimi, C.R., Haase, J.E., & Kooken, W.C. (2012). Connectedness in the context of patient–provider relationships: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68, 230–245.

Plante, A., & Joannette, S. (2009). Montérégie Comprehensive Cancer Care Centre: Integrating nurse navigators in Montérégie’s oncology teams: One aspect of implementing the Cancer Control Program—Part 1. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 19(1), 13–18. doi:10.5737/1181912x1911318

Polit, D.E., & Beck, C.T. (2008). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Radwin, L.E. (1996). ‘Knowing the patient’: A review of research on an emerging concept. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 23, 1142–1146. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.12910.x

Radwin, L.E. (2000). Oncology patients’ perceptions of quality nursing care. Research in Nursing and Health, 23, 179–190.

Radwin, L.E., & Alster, K. (2002). Individualized nursing care: An empirically generated definition. International Nursing Review, 49, 54–63. doi:10.1046/j.1466-7657.2002.00101.x

Rauch, P.K., Muriel, A.C., & Cassem, N.H. (2002). Parents with cancer: Who’s looking after the children? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20, 4399–4402.

Semple, C.J., & McCance, T. (2010). Parents’ experience of cancer who have young children: A literature review. Cancer Nursing, 33, 110–118. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c024bb

Suhonen, R., Valimaki, M., & Leino-Kilpi, H. (2009). The driving and restraining forces that promote and impede the implementation of individualised nursing care: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46, 1637–1649. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.05.012

Takemura, Y., & Kanda, K. (2003). How Japanese nurses provide care: A practice based on continuously knowing the patient. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 42, 252–259. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02614.x

Thorne, S., Oliffe, J., Kim-Sing, C., Hislop, T.G., Stajduhar, K., Harris, S.R., . . . Oglov, V. (2010). Helpful communications during the diagnostic period: An interpretive description of patient preferences. European Journal of Cancer Care, 19, 746–754.

Thorne, S.E., Kuo, M., Armstrong, E.A., McPherson, G., Harris, S.R., & Hislop, T.G. (2005). ‘Being known’: Patients’ perspectives of the dynamics of human connection in cancer care. Psycho-Oncology, 14, 887–898. doi:10.1002/pon.945

Thygesen, M.K., Pedersen, B.D., Kragstrup, J., Wagner, L., & Mogensen, O. (2011). Benefits and challenges perceived by patients with cancer when offered a nurse navigator. International Journal of Integrated Care, 11, e130.

Whittemore, R. (2000). Consequences of not ‘knowing the patient’. Clinical Nurse Specialist, 14, 75–81. doi:10.1097/00002800-200003000-00010

Wilkinson, S. (1991). Factors which influence how nurses communicate with cancer patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 16, 677–688. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1991.tb01726.x

Zebrack, B., Bleyer, A., Albritton, K., Medearis, S., & Tang, J. (2006). Assessing the health care needs of adolescent and young adult cancer patients and survivors. Cancer, 107, 2915–2923. doi:10.1002/cncr.22338

Zebrack, B., Chesler, M.A., & Kaplan, S. (2010). To foster healing among adolescents and young adults with cancer: What helps? What hurts? Supportive Care in Cancer, 18, 131–135. doi:10.1007/s00520-009-0719-y

Zebrack, B.J., Mills, J., & Weitzman, T.S. (2007). Health and supportive care needs of young adult cancer patients and survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 1, 137–145.

About the Author(s)

Susanna K. Jacobsen, RN, MSc(A), and Gabrielle M. Bouchard, RN, MSc(A), are nurse clinicians; Jessica Emed, RN, MSc(A), is a clinical nurse specialist; and Karine Lepage, RN, MSc, and Erin Cook, RN, MN, are head nurses, all at the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal, Quebec. No financial relationships to disclose. Jacobsen can be reached at susanna.jacobsen@mail.mcgill.ca, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted September 2014. Accepted for publication December 12, 2014.)