Survivorship Care Plans and Treatment Summaries in Adult Patients With Hematologic Cancer: An Integrative Literature Review

Problem Identification: Survivorship care plans (SCPs) and treatment summaries (TSs) have been recommended by the Institute of Medicine as ways to facilitate the delivery of holistic survivorship care. An integrative literature review was undertaken to identify current use of SCPs and TSs to meet the needs of survivors of hematologic cancer.

Literature Search: Databases searched for eligible articles were CINAHL®, the Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE®, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, and PubMed.

Data Evaluation: Four articles that reported on experience, dissemination, or components of SCPs or TSs were included. Hematology-specific literature was limited, and no randomized, controlled trials or literature reviews were found for the cohort of survivors of hematologic cancer.

Synthesis: Content analysis was used to summarize the findings.

Conclusions: High-quality evidence evaluating the effectiveness of SCPs and TSs on hematologic cancer survivorship follow-up care is lacking. Nurses have established expertise in health promotion, information, support, and resource provision; they can develop and disseminate SCPs and TSs to facilitate communication among the survivor, specialist, and primary care provider.

Implications for Research: Well-designed, randomized, controlled trials on SCPs and TSs are required, particularly for cancers not well represented in the literature.

Jump to a section

Survivorship, as defined by the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (2014), is the experience of living with, through, and beyond a diagnosis of cancer, including the impact on family, friends, and caregivers. Survivorship care is recognized as a priority in the cancer care continuum and has largely been driven by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition (Hewitt, Greenfield, & Stovall, 2005). A key recommendation of this report was the provision of a survivorship care plan (SCP) and treatment summary (TS) for all survivors (Palmer et al., 2014). Following the release of the report, many countries around the world developed and initiated national cancer initiatives (McCabe, Faithfull, Makin, & Wengstrom, 2013). Survivorship care should include the following components (Grant & Economou, 2008; Landier, 2009; Rechis, Arvey, & Beckjord, 2013). •

Coordination of care among providers to communicate overall health needs

• Monitoring, information about, and promotion of healthy living behaviors and disease prevention (e.g., guidelines for diet and exercise, alcohol consumption, tobacco cessation, sun protection, and healthy weight management)

• Prevention, screening, and intervention for recurrence, as well as long-term and late effects; early detection of new cancers or second malignancies by adherence to recommended surveillance guidelines (e.g., colonoscopies, mammograms, Papanicolaou tests, skin checks); and awareness of comorbidities

• Psychosocial well-being assessment, support, management, and information provision for physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs

Routine follow-up care focuses largely on surveillance for recurrence and the monitoring of physical side effects, neglecting supportive care, health promotion, late-effects monitoring, and surveillance for new cancers (de Leeuw & Larsson, 2013). Awareness of the suboptimal communication that occurs between healthcare professionals, including primary care providers (PCPs), and patients is increasing; important information is often not provided at treatment completion (Dicicco-Bloom & Cunningham, 2013; McCabe & Jacobs, 2012). In addition, patients with cancer frequently experience multiple health problems earlier than the general population (Panek-Hudson, 2013). As such, a need exists for comprehensive early and ongoing approaches to management; these should take advantage of teachable moments at the end of active treatment to promote and support patient participation in maximizing recovery by the adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviors (Alfano, Ganz, Rowland, & Hahn, 2012; Grant & Economou, 2008; Hewitt et al., 2005; Panek-Hudson, 2013).

The provision of SCPs or TSs has been seen as an important element of communication with survivors and multidisciplinary healthcare providers. What appears to be an obvious solution to ensuring optimal follow-up and recommendation adherence is hampered by the complexity of cancer types and treatment. This problem is particularly evident within hematologic cancers, which are made up of diverse blood, immune, and bone marrow diseases that make standardization of inclusions very difficult (Rechis et al., 2013). This survivor cohort lacks clear guidelines for follow-up care (Earle, 2007; Phillips & Currow, 2010; Rechis et al., 2013).

The three main types of hematologic cancer are leukemia, lymphoma, and myeloma (American Society of Hematology, 2015). Each cancer type has distinctive and complex treatment regimens that commonly involve high-dose chemotherapy agents, as well as targeted therapy, radiation therapy, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Carey et al., 2012); these regimens often take place at different institutions. Unfortunately, a number of long-term and late physical, practical, and psychosocial effects that commonly include fear of recurrence, fatigue, and issues related to nutrition, exercise, fertility, relationships, finances, employment, and insurance can result from these largely aggressive treatments (Allart, Soubeyran, & Cousson-Gélie, 2013; Hall, Lynagh, Bryant, & Sanson-Fisher, 2013). Patients with hematologic cancer require SCPs or TSs that reflect disease-specific differences instead of those designed for patients with more common cancers (e.g., breast, prostate, colorectal) that follow similar patterns of survivorship and are widely available.

Patients with hematologic cancer are understudied and underrepresented in survivorship care (Swash, Hulbert-Williams, & Bramwell, 2014), despite internationally increasing five-year relative survival rates (Sant et al., 2014). The hematology focus of this integrative review will add to the limited body of knowledge available regarding this cohort of survivors.

This review undertook an analysis of the literature primarily to examine the common attributes of SCPs and TSs developed for patients with hematologic cancer, including (a) resources (e.g., human, templates) required to develop SCPs and TSs, (b) potential benefits and limitations of SCPs and TSs, and (c) outcome measures that have been used to evaluate SCPs and TSs, as well as the findings of those measures.

Methods

The integrative review method was chosen because it allows for an in-depth evaluation of the issues encompassing the empirical, theoretical, and clinical approaches within a structured systematic methodology (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). The method is structured according to five stages: problem formulation, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

Problem Formulation

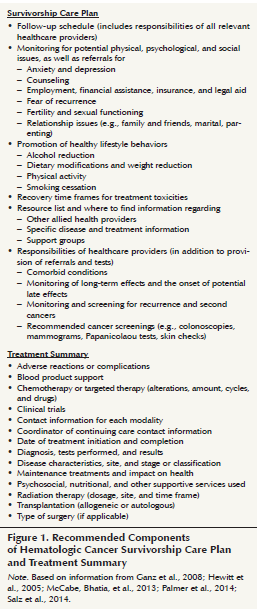

In the current review, an SCP is defined as a personalized document that guides and coordinates follow-up care (e.g., recommended surveillance, screening, health-promoting behaviors) in addition to providing information, education, and resources for the management of potential long-term and late effects of cancer treatment (Hausman, Ganz, Sellers, & Rosenquist, 2011; Salz et al., 2014). Within cancer survivorship, a TS specifically refers to comprehensively summarized information regarding disease, procedures, and treatments received for a particular cancer (Hausman et al., 2011; Jabson & Bowen, 2013). The aim of these tools is to provide written communication from the treatment team to survivor, as well as clear delineation of responsibility of care to current and future healthcare providers (Earle, 2006; McCabe, Bhatia, et al., 2013). A number of components have been proposed for inclusion in SCPs and TSs based on recommendations from the IOM (Hewitt et al., 2005). An overview of relevant components for survivors of hematologic cancer are listed in Figure 1 and have been adapted from the published literature.

Much of the responsibility for the creation and dissemination of SCPs and TSs rests with the treating team (Earle, 2007; Hausman et al., 2011; Hewitt, Bamundo, Day, & Harvey, 2007; McCabe, Faithfull, et al., 2013; Salz et al., 2014; Stricker et al., 2011). However, the development of such individualized tools is time consuming, particularly if treatment occurs across multiple sites and if a lack of integration or absence of electronic records exists (Earle, 2007; McCabe, Bhatia, et al., 2013; Parry, Kent, Forsythe, Alfano, & Rowland, 2013; Rechis et al., 2013; Salz et al., 2014). Nurses have been suggested as the logical choice to create and deliver SCPs and TSs, not only to free up specialists’ time but also because of their well-established role in providing holistic, individualized information to patients (Jackson, Scheid, & Rolnick, 2013; Marbach & Griffie, 2011).

Templates can reduce the time required to complete SCPs and TSs, providing that the required information is readily accessible. The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and Lippincott’s NursingCenter.com provide three-page downloadable templates (McCabe, Partridge, Grunfeld, & Hudson, 2013). Once the pertinent information is provided, Internet-based SCP tools, such as the Journey Forward Survivorship Care Plan Builder and the LIVESTRONG® Care Plan (Hausman et al., 2011), deliver a comprehensive summary and a detailed long-term follow-up plan of care. However, their use is limited by the length (14 pages) of the tool (McCabe, Partridge, et al., 2013). For survivors and healthcare professionals outside of the United States, the available educational and supportive care resources may not be applicable. Hill-Kayser et al. (2013) studied use and satisfaction of the LIVESTRONG Care Plan and found that a majority (93%, n = 276) of responding survivors had rated the provision and amount of information as good to excellent. About 65% (n = 186) of responding survivors had not been given information contained in the SCP by healthcare providers after treatment completion. In addition, psychosocial concerns or risks were often not addressed, thereby necessitating later delivery after a healthcare professional had performed a follow-up needs assessment (Belansky & Mahon, 2012). Ganz, Casillas, & Hahn (2008) and Stricker et al. (2011) proposed that a dedicated survivorship visit would be ideal to assess patient needs and to deliver SCPs and TSs; however, they did not stipulate when that visit should take place.

The majority of studies regarding SCPs and TSs are largely descriptive or exploratory and have not established evidence showing that the use of SCPs and TSs improves survivor outcomes (Grant & Economou, 2008; McCabe, Faithfull, et al., 2013). A randomized, controlled trial of patients with breast cancer by Grunfeld et al. (2011) compared SCP provision to PCPs with usual care (no SCP); the study showed no difference in patient-reported outcomes between the two groups. However, this study has been criticized (Jefford, Schofield, & Emery, 2012; Stricker, Jacobs, & Palmer, 2012) because control PCPs received a comprehensive discharge letter that may have contained recommendations for follow-up care. Both groups may have received similar information, albeit in different formats, so results should be viewed with caution because of potential contamination of the control group. Because published literature in hematologic cancer survivorship is rare, the focus of this integrative review was to identify SCPs and TSs used with survivors of hematologic cancer to facilitate the development of tools that can be used with this unique survivor cohort.

Literature Search

The primary search took place from January 2000 to July 2014 and used the CINAHL®, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, MEDLINE®, PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, and PubMed electronic databases. Combinations of the following search terms were used: survivorship care plan OR treatment summary OR follow-up care plan OR post-treatment plan OR written follow-up instructions AND survivorship OR cancer survivor AND cancer OR neoplasm OR oncology AND hematology OR leukemia OR lymphoma OR multiple myeloma. A hand search of reference lists from full texts was also employed. Searches were restricted to the English language, humans, and adults. Inclusion criteria were (a) studies that reported on SCP and TS use during the post-treatment phase of hematologic cancer survivorship and (b) studies that reported usage perceptions of SCPs and TSs experienced by healthcare providers and survivors. Exclusion criteria were (a) studies with less than a 25% cohort of patients with hematologic cancer or hematologist viewpoint; (b) studies that reported perceptions of, rather than experiences with, SCP and TS use; (c) studies reporting SCPs and TSs from child, adolescent, adult survivors of a childhood cancer, or non-cancer populations; and (d) opinion papers, letters, editorials, commentaries, conference abstracts, conference proceedings, or case studies.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"19466","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"409","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"365"}}]]

Data Evaluation Stage

Abstract titles were reviewed to assess eligibility. A summary of the selection process (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009) is provided in Figure 2. The initial search yielded 697 abstracts. Duplicate articles were removed, and abstracts were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Abstracts that did not provide cancer or provider type were sought for further screening. Twenty full-text articles were retrieved; of those, four articles were reviewed. Documented methodologic characteristics included author information, study design and intervention, sample characteristics (e.g., participant details, response rate, years post-treatment), outcome measures, results, limitations and comments, and level of evidence as developed by Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt (2011) (see Table 1). Because of variations in study population and methodologies used, meta-analysis was not possible.

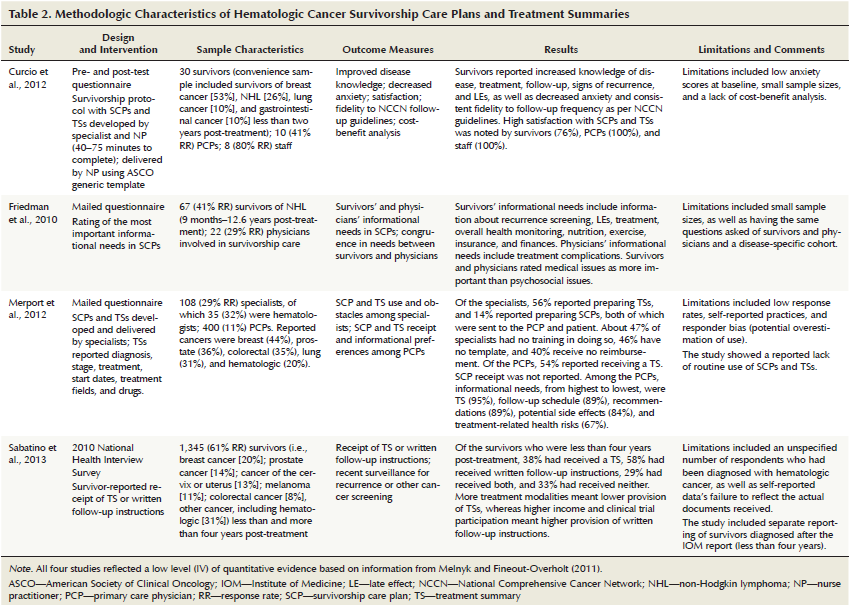

The hematology component in the majority of studies was low. No systematic reviews on studies related to SCPs and TSs were identified. The four included studies were all from the United States. They assessed survivor and clinician views on the experience of receiving or disseminating SCPs and TSs. Included articles used various terms to describe treating clinicians. For clarity in this article, the term “specialist” will refer to the following treating consultants: hematologist and medical or radiation oncologist. The research studies all used quantitative approaches and reflected a low level (IV) of quantitative evidence. Reviewed studies were related to the survivorship phase of the cancer trajectory. Characteristics of reviewed articles are detailed in Table 2.

Data Analysis and Presentation

Sabatino et al. (2013) reported a subset of survivors (n = 407) who were within four years of diagnosis—a time frame corresponding with the IOM report’s recommendation that all survivors receive SCPs and TSs. Survivors were asked if they had ever received a SCP or TS. The authors found that 38% (n = 155) of survivors acknowledged receipt of a TS, and that 58% (n = 236) had received written follow-up instructions. Written follow-up instructions were received more often by those patients who were part of a clinical trial (85%, n = 346) and by those who were reported as having a higher income (67%, n = 274). Survivors who had undergone hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were included; however, numbers were not reported.

Curcio, Lambe, Schneider, and Kahn (2012) studied survivors and clinicians. Survivors of hematologic cancer accounted for 26% (n = 8) of the overall survivor cohort studied (n = 30). Survivors were highly satisfied with the provision of SCPs and TSs and reported an increase in knowledge. Anxiety levels decreased, although levels were not high at baseline and may have decreased naturally with time. Survivor satisfaction may have been related to the survivorship visit and follow-up telephone call rather than SCP provision. PCPs were reported as being satisfied (100%, n = 10) with SCPs and TSs. The authors reported that PCPs appreciated the content, which aided communication and was useful in providing clarification of the survivor’s follow-up plan.

Friedman, Coan, Smith, Herndon, and Abernethy (2010) studied survivors of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (n =67) and physicians (n = 22) involved in survivorship care. Informational needs in the SCP were reported as being congruent between the PCP and survivor. All respondents rated medical content as more important than psychosocial issues, perhaps reflecting survivor expectations in the current model of survivorship follow-up. In addition, survivors ranked the plan to monitor overall health the sixth most important element of the SCP as compared to physicians who ranked it 13th. This led the authors to conclude that survivors view follow-up as part of general health maintenance, whereas physicians separate cancer survivorship care and non-cancer–related care.

Merport, Lemon, Nyambose, and Prout (2012) evaluated clinician (n = 108) use and PCP (n = 400) receipt of SCPs and TSs. About 54% (n = 216) of PCPs received a TS. However, the study reported that only 42% (n = 46) of specialists, including hematologists, prepared a TS. SCP preparation by specialists was low at 14% (n = 15); however, the authors reported that all SCPs were sent to survivors and PCPs. Barriers identified in this study included the lack of a template and of training given to healthcare professionals regarding the development of SCPs and TSs, as well as specialists’ perceived absence of financial reimbursement for their time spent developing and delivering SCPs and TSs. The absence of support from treating clinicians may mean that development and dissemination remain low, with the possibility that SCPs stay medically focused.

These four studies all showed a lack of routine use of SCPs and TSs, although survivors and PCPs reported that they valued the tools and the direction for survivorship follow-up care that they provided.

Discussion

Published hematology research regarding SCPs and TSs is limited. No randomized, controlled trials or literature reviews exist for this understudied cohort of survivors, despite the belief that SCPs and TSs are beneficial to complex and rare survivor groups (e.g., hematology) (Shalom, Hahn, Casillas, & Ganz, 2011) in which health problems may take many years to develop (Sabatino et al., 2013). With the increased risk of psychosocial, physical, and economic long-term and late effects from disease and cancer therapy, patients often experience difficulties accessing post-treatment follow-up, which may lead to poorer overall health outcomes (Friedman et al., 2010).

Within the literature that reported the development and dissemination of the SCP and TS (Curcio et al., 2012; Merport et al., 2012), a lack of information regarding resources used by the specialist to develop the SCP and TS was observed (Merport et al., 2012). Similarly, information concerning how generic templates were tailored by the specialist and nurse practitioner to different survivors was not provided (Curcio et al., 2012). Details on any evidence-based guidelines for follow-up care used in SCPs (Merport et al., 2012) and the clinical expertise of the health professionals creating SCPs and TSs was equally lacking.

Standardized templates linked to electronic health records that would directly populate TSs have been proposed to provide health providers with diagnosis and treatment information (Merport et al., 2012; Salz et al., 2014); doing so would be particularly relevant when survivors have had treatment across a number of sites (Merport et al., 2012). Sabatino et al. (2013) found low TS and SCP delivery when survivors had more than one treatment modality. The long duration of treatment that occurs in some hematologic cancer regimens can make difficult the finding and summarizing of modifications and issues that have occurred during the entire treatment phase. Guidelines and templates for SCPs and TSs specific to hematologic cancers are necessary because generic cancer templates cannot convey all of the appropriate information required, adding to the complexity of this issue (Friedman et al., 2010). Curcio et al. (2012) and Sabatino et al. (2013) noted that the provision of SCPs and TSs soon after treatment completion is required to assess the need for information and resources.

Friedman et al. (2010) argued that providing extra information to survivors could overload and dilute the impact of the most important information that needs to be conveyed. This view is supported by Cox and Faithfull (2013) who reported that clinicians consider late-effects information to affect psychological adjustment and increase the amount of late effects through autosuggestion. However, these authors reflect the perception of clinicians rather than patients, and, as Hill-Kayser et al. (2013) argued, this paternalistic approach is no longer acceptable. Providing tailored SCPs and TSs to survivors empowers individuals to learn about their disease and treatment and assume responsibility for future surveillance and disease management, facilitating engagement in a future healthy lifestyle (Jackson et al., 2013). This is particularly vital for younger survivors, given the expectation of a longer survivorship period (Jabson & Bowen, 2013).

Multidisciplinary collaboration has been suggested (Shalom et al., 2011) as a strategy for developing SCPs and TSs. Interdisciplinary education must acknowledge the value of each provider’s contribution within the team. Recommendations clearly detailing provider responsibility can help to ensure that survivors are not over- or undertested and that they adhere to evidence- or consensus-based recommendations (Curcio et al., 2012). However, caution must be exercised when using consensus-based recommendations.

Nurses can be a key component in implementing care plans and providing comprehensive information, education, and resources, particularly in preventive health and screening (Curcio et al., 2012). Shalom et al. (2011) revealed that nurse practitioner-developed SCPs may not be read by PCPs—100% (n = 15) of PCPs reported that they would not act on expensive testing recommendations. Consequently, specialists must reinforce the importance of nurses as an essential component of survivorship care planning (Hewitt et al., 2007).

SCPs and TSs should be developed in conjunction with a robust model of hematologic cancer survivorship follow-up care that will address the issues and barriers related to implementation. Many professional organizations are calling for SCP development for accreditation. However, cancer programs that develop SCPs solely to meet professional requirements may be reluctant to make the organizational changes necessary to actually deliver the SCPs to survivors and PCPs (Birken, Mayer, & Weiner, 2013). Institutions and specialists perceiving a lack of financial reimbursement and support for the additional time required to prepare and deliver SCPs and TSs may be disinclined to support widespread implementation (Earle, 2007; McCabe, Partridge, et al., 2013; Salz et al., 2014).

The authors acknowledge several limitations of the current review. The search revealed a small number of articles meeting inclusion criteria. All studies reviewed had low sample numbers and response rates, particularly those studies that explored PCP experiences of SCPs and TSs. The numbers of survivors of hematologic cancer were limited, decreasing the applicability of findings to survivors of hematologic cancer. The reliance on self-reported practices in all four of the studies and a lack of comparison groups restrict the conclusions that can be drawn. Study participants may have had more experience with SCPs and TSs, as well as a bias toward or against SCP and TS implementation. This lack of standardization makes comparing studies and drawing conclusions regarding benefits to survivors difficult. In addition, an inherent bias in interpretation may be related to the evaluator.

Implications for Nursing

This integrative review identified published literature on SCPs and TSs and their applicability to survivors of hematologic cancer. Treatment advances in hematologic cancer mean that patients are living longer (Sant et al., 2014); however, the extended recovery trajectory involves a heavier symptom burden and post-treatment complications because of the aggressive nature of the hematologic disease and the treatment required. These hematologic cancers are unlike the other cancers that are often used as benchmarks (e.g., breast cancer, prostate cancer) (Parry, Morningstar, Kendall, & Coleman, 2011).

Nurses can influence and guide the development of relevant survivorship care recommendations, thereby facilitating a paradigm shift to encompass all aspects of the cancer trajectory. Nurses with advanced research skills (e.g., PhD prepared) would be well placed to take the lead in adopting and translating follow-up guidelines for patients with hematologic cancer into evidence-based and disease-specific templates. Nurses are in a unique position to provide and disseminate SCPs and TSs comprising individualized and relevant resources, information, and education to ensure that the needs of survivors of hematologic cancer are met. Nurses must also support and empower survivors to take control of and, ultimately, self-manage their ongoing needs.

The current review revealed a lack of high-quality evidence related to the care of survivors of hematologic cancer. Addressing the specific and ongoing concerns of these patients, along with disseminating this information to survivors and clinicians, particularly in primary care, is important. As survival rates continue to increase, the successful integration of hematologic cancer survivorship care into the cancer continuum is vital.

Conclusion

Further research will need to account for the inclusion of each component of the SCP, the survivor’s desire for this knowledge and information, and the best way to develop and deliver SCPs and TSs that are specific to hematologic cancer. Research is required regarding the models of care that are most suitable for delivering SCPs and TSs to survivors of hematologic cancer, including their perspectives on follow-up provision. Nurse-led hematology survivorship clinics that facilitate shared care between the treating team and PCPs may be the most appropriate model to deliver SCPs and TSs. This may help to achieve the best outcomes for patients transitioning into the survivorship period but requires further evidence-based research. Methods that will optimize communication and clarity with provider responsibility, decreasing overuse or underuse of surveillance and screening tests, are fundamental aspects of this research. Research in how best to decrease the amount of time needed to prepare SCPs and TSs and the ideal time to effectively deliver SCPs and TSs is necessary. Well-designed, pragmatic, randomized, controlled trials are required to inform clinical practice. As the amount of outcome-based research increases, so too will the understanding of providing optimal survivorship care.

References

Alfano, C.M., Ganz, P.A., Rowland, J.H., & Hahn, E.E. (2012). Cancer survivorship and cancer rehabilitation: Revitalizing the link. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 904–906. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.37.1674

Allart, P., Soubeyran, P., & Cousson-Gélie, F. (2013). Are psychosocial factors associated with quality of life in patients with haematological cancer? A critical review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 241–249. doi:10.1002/pon.3026

American Society of Hematology. (2015). Blood cancers. Retrieved from http://www.hematology.org/Patients/Cancers

Belansky, H., & Mahon, S.M. (2012). Using care plans to enhance care throughout the cancer survivorship trajectory. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 90–92. doi:10.1188/12.CJON.90-92

Birken, S.A., Mayer, D.K., & Weiner, B.J. (2013). Survivorship care plans: Prevalence and barriers to use. Journal of Cancer Education, 28, 290–296. doi:10.1007/s13187-013-0469-x

Carey, M., Anderson, A., Sanson-Fisher, R., Lynagh, M., Paul, C., & Tzelepis, F. (2012). How well are we meeting haematological cancer survivors’ preferences for involvement in treatment decision making? Patient Education and Counseling, 88, 87–92. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2011.12.014

Cox, A., & Faithfull, S. (2013). ‘They’re survivors physically but we want them to survive mentally as well’: Health care professionals’ views on providing potential late effect information. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21, 2491–2497. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1806-7

Curcio, K.R., Lambe, C., Schneider, S., & Khan, K. (2012). Evaluation of a cancer survivorship protocol: Transitioning patients to survivors. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 400–406. doi:10.1188/12.CJON.400-406

de Leeuw, J., & Larsson, M. (2013). Nurse-led follow-up care for cancer patients: What is known and what is needed. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21, 2643–2649. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1892-6

Dicicco-Bloom, B., & Cunningham, R.S. (2013). The experience of information sharing among primary care clinicians with cancer survivors and their oncologists. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 7, 124–130. doi:10.1007/s11764-012-0253-7

Earle, C.C. (2006). Failing to plan is planning to fail: Improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 24, 5112–5116. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5284

Earle, C.C. (2007). Long term care planning for cancer survivors: A health services research agenda. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 1, 64–74. doi:10.1007/s11764-006-0003-9

Friedman, D.R., Coan, A.D., Smith, S.K., Herndon, J.E., II, & Abernethy, A.P. (2010). Informational needs assessment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors and their physicians. American Journal of Hematology, 85, 528–532. doi:10.1002/ajh.21725

Ganz, P.A., Casillas, J., & Hahn, E.E. (2008). Ensuring quality care for cancer survivors: Implementing the survivorship care plan. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 24, 208–217. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2008.05.009

Grant, M., & Economou, D. (2008). The evolving paradigm of adult cancer survivor care. Oncology, 22, 13–22, 27.

Grunfeld, E., Julian, J.A., Pond, G., Maunsell, E., Coyle, D., Folkes, A., . . . Levine, M.N. (2011). Evaluating survivorship care plans: Results of a randomized, clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29, 4755–4762. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8373

Hall, A., Lynagh, M., Bryant, J., & Sanson-Fisher, R. (2013). Supportive care needs of hematologic cancer survivors: A critical review of the literature. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 88, 102–116. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.03.008

Hausman, J., Ganz, P.A., Sellers, T.P., & Rosenquist, J. (2011). Journey forward: The new face of cancer survivorship care. Jounal of Oncology Practice, 7(Suppl. 3), e50s–e56s. doi:10.1200/JOP.2011.000306

Hewitt, M., Greenfield, S., & Stovall, E. (Eds.). (2005). From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Hewitt, M.E., Bamundo, A., Day, R., & Harvey, C. (2007). Perspectives on post-treatment cancer care: Qualitative research with survivors, nurses, and physicians. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 2270–2273. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.10.0826

Hill-Kayser, C.E., Vachani, C.C., Hampshire, M.K., Di Lullo, G., Jacobs, L.A., & Metz, J.M. (2013). Impact of internet-based cancer survivorship care plans on health care and lifestyle behaviors. Cancer, 119, 3854–3860. doi:10.1002/cncr.28286

Jabson, J.M., & Bowen, D.J. (2013). Cancer treatment summaries and follow-up care instructions: Which cancer survivors receive them? Cancer Causes and Control, 24, 861–871. doi:10.1007/s10552-013-0163-7

Jackson, J.M., Scheid, K., & Rolnick, S.J. (2013). Development of the cancer survivorship care plan: What’s next? Life after cancer treatment. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17, 280–284. doi:10.1188/13.CJON.280-284

Jefford, M., Schofield, P., & Emery, J. (2012). Improving survivorship care. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 1391–1392. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.40.5886

Landier, W. (2009). Survivorship care: Essential components and models of delivery. Oncology, 23, 46–53.

Marbach, T.J., & Griffie, J. (2011). Patient preferences concerning treatment plans, survivorship care plans, education, and support services. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38, 335–342. doi:10.1188/11.ONF.335-342

McCabe, M.S., Bhatia, S., Oeffinger, K.C., Reaman, G.H., Tyne, C., Wollins, D.S., & Hudson, M.M. (2013). American Society of Clinical Oncology statement: Achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, 631–640. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854

McCabe, M.S., Faithfull, S., Makin, W., & Wengstrom, Y. (2013). Survivorship programs and care planning. Cancer, 119, 2179–2186. doi:10.1002/cncr.28068

McCabe, M.S., & Jacobs, L.A. (2012). Clinical update: Survivorship care—Models and programs. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 28, e1–e8. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2012.05.001

McCabe, M.S., Partridge, A.H., Grunfeld, E., & Hudson, M.M. (2013). Risk-based health care, the cancer survivor, the oncologist, and the primary care physician. Seminars in Oncology, 40, 804–812. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2013.09.004

Melnyk, B.M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2011). Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: A guide to best practice (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Merport, A., Lemon, S.C., Nyambose, J., & Prout, M.N. (2012). The use of cancer treatment summaries and care plans among Massachusetts physicians. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20, 1579–1583. doi:10.1007/s00520-012-1458-z

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D.G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535

National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship. (2014). Defining cancer survivorship. Retrieved from http://www.canceradvocacy.org/news/defining-cancer-survivorship

Palmer, S.C., Jacobs, L.A., DeMichele, A., Risendal, B., Jones, A.F., & Stricker, C.T. (2014). Metrics to evaluate treatment summaries and survivorship care plans: A scorecard. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22, 1475–1483. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-2107-x

Panek-Hudson, Y. (2013). Survivorship care—Time for innovation? Australian Journal of Cancer Nursing, 14, 7–12.

Parry, C., Kent, E.E., Forsythe, L.P., Alfano, C.M., & Rowland, J.H. (2013). Can’t see the forest for the care plan: A call to revisit the context of care planning. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, 2651–2653. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.48.4618

Parry, C., Morningstar, E., Kendall, J., & Coleman, E.A. (2011). Working without a net: Leukemia and lymphoma survivors’ perspectives on care delivery at end-of-treatment and beyond. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 29, 175–198. doi:10.1080/07347332.2010.548444

Phillips, J.L., & Currow, D.C. (2010). Cancer as a chronic disease. Collegian, 17, 47–50. doi:10.1016/j.colegn.2010.04.007

Rechis, R., Arvey, S.R., & Beckjord, E.B. (2013). Perspectives of a lifelong cancer survivor—Improving survivorship care. Nature Reviews. Clinical Oncology, 10, 117–120. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.212

Sabatino, S.A., Thompson, T.D., Smith, J.L., Rowland, J.H., Forsythe, L.P., Pollack, L., & Hawkins, N.A. (2013). Receipt of cancer treatment summaries and follow-up instructions among adult cancer survivors: Results from a national survey. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 7, 32–43. doi:10.1007/s11764-012-0242-x

Salz, T., McCabe, M.S., Onstad, E.E., Baxi, S.S., Deming, R.L., Franco, R.A., . . . Oeffinger, K.C. (2014). Survivorship care plans: Is there buy-in from community oncology providers? Cancer, 120, 722–730. doi:10.1002/cncr.28472

Sant, M., Minicozzi, P., Mounier, M., Anderson, L.A., Brenner, H., Holleczek, B., . . . De Angelis, R. (2014). Survival for haematological malignancies in Europe between 1997 and 2008 by region and age: Results of EUROCARE-5, a population-based study. Lancet Oncology, 15, 931–942. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70282-7

Shalom, M.M., Hahn, E.E., Casillas, J., & Ganz, P.A. (2011). Do survivorship care plans make a difference? A primary care provider perspective. Journal of Oncology Practice, 7, 314–318. doi:10.1200/JOP.2010.000208

Stricker, C.T., Jacobs, L.A., & Palmer, S. C. (2012). Survivorship care plans: An argument for evidence over common sense. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 30, 1392–1393. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7940

Stricker, C.T., Jacobs, L.A., Risendal, B., Jones, A., Panzer, S., Ganz, P.A., . . . Palmer, S.C. (2011). Survivorship care planning after the Institute of Medicine recommendations: How are we faring? Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 5, 358–370. doi:10.1007/s11764-011-0196-4

Swash, B., Hulbert-Williams, N., & Bramwell, R. (2014). Unmet psychosocial needs in haematological cancer: A systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 22, 1131–1141. doi:10.1007/s00520-014-2123-5

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52, 546–553. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

About the Author(s)

Karen Taylor, MNurs, GradDipOnc, BN, RN, is a survivorship cancer nurse coordinator at the Western Australia Cancer and Palliative Care Network in Perth and a PhD candidate in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at the University of Notre Dame Australia in Fremantle, and Leanne Monterosso, PhD, BNurs (Hons1), GCert Teach, FACN, is a professor in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at the University of Notre Dame Australia and in the School of Nursing and Midwifery at Edith Cowan University in Joondalup and an honorary professor in the School of Health Professions at Murdoch University in Perth. No financial relationships to disclose. Taylor can be reached at karen.taylor@health.wa.gov.au,with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted October 2014. Accepted for publication December 12, 2014.)