African American Women’s Recollected Experiences of Adherence to Breast Cancer Treatment

Purpose/Objectives: To explore African American women’s recollected experiences of breast cancer treatment.

Research Approach: Qualitative description and narrative analysis.

Setting: South Carolina Oncology Associates, an outpatient oncology clinic serving rural and urban populations.

Participants: 16 African American women with breast cancer previously enrolled in the control arm (n = 93) of a completed randomized, controlled trial.

Methodologic Approach: Feminist narrative analysis of in-depth individual interviews.

Findings: The authors identified three themes within the African American breast cancer survivors’ recollected experiences of treatment adherence: Embarking With Trust, Moving on Down the Road, and Being Actively Involved in Decision Making.

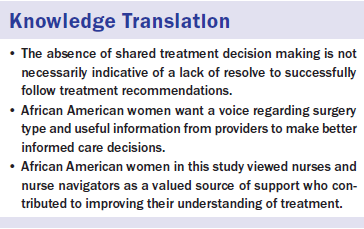

Interpretation: Although little evidence was presented of shared decision making with providers, patients were committed to completing the prescribed therapies. The narratives highlighted the value of in-depth examination of patients’ perspectives, particularly among minority and underserved groups. With the exception of voicing personal choice of surgical treatment, the women trusted providers’ recommendations with a resolve to “just do it.” Although trust may enhance treatment adherence, it may also reflect power differentials based on gender, race, education, and culture.

Implications for Nursing: Nurses should listen to patients describe their experience with cancer treatment and compare the themes from this study with their patients’ story. This comparison will help nurses support patients through various aspect of diagnosis and treatment.

Jump to a section

The breast cancer mortality rate among African American women is 42% higher than that of Caucasian women (Howlader et al., 2015), even with equivalent cancer stage and treatment (Albain, Unger, Crowley, Coltman, & Hershman, 2009; Berz et al., 2009). About 6,300 African American women die from breast cancer in the United States each year (American Cancer Society, 2016). Early discontinuation or failure to receive recommended treatment is highly associated with mortality (Hershman et al., 2011). Although improved treatment adherence could potentially decrease this mortality gap (Hassett & Griggs, 2009), limited research has been conducted on African American women’s adherence to radiation or parenteral chemotherapy (Magai, Consedine, Adjei, Hershman, & Neugut, 2008; Wells, Strickland, Dalton, & Freeman, 2014). For the purpose of this article, the authors defined treatment adherence as treatment completed as recommended (Gould & Mitty, 2010). Current literature suggests that the term compliance could be seen as pejorative and reflects a power differential between provider and patient. The authors used the term adherence to suggest that treatment is not something done to a patient but is a shared goal among patients and providers for patient-centered care.

Studies of radiation and chemotherapy adherence among African American patients with breast cancer have produced conflicting findings (Banerjee, George, Yee, Hryniuk, & Schwartz, 2007; Bickell et al., 2006; Hershman et al., 2009, 2010, 2011). In a retrospective review of breast cancer treatment among a predominantly African American sample (n = 93 of 107), 43% refused the recommended chemotherapy or radiation treatment (Rizzo et al., 2009). However, Sharma, Harris, Haffty, Yang, and Moran (2010) reported comparable levels of radiation treatment adherence among African American and Caucasian patients. In addition, Andic et al. (2011) reported similar treatment compliance rates among African American and Caucasian women with inflammatory breast cancer. Patient-identified barriers include financial concerns, communication barriers, negative interactions with providers, treatment knowledge deficits, and limited decision-making involvement (Darby, Davis, Likes, & Bell, 2009; Kreling, Figueiredo, Sheppard, & Mandelblatt, 2006; Rust & Davis, 2011; Sheppard, Adams, Lamdan, & Taylor, 2011; Sheppard et al., 2009; Song, Hamilton, & Moore, 2011).

Better understanding of African American women’s breast cancer treatment experiences is necessary for the provision of culturally tailored care aimed at enhancing treatment acceptance and adherence. Using a descriptive approach (Sandelowski, 2000), the authors explored African American patients’ recollections of their radiation and chemotherapy treatment for breast cancer in an effort to gain a better understanding of what might promote adherence.

Methodologic Approach

The multidisciplinary team contributed diverse content and methodologic expertise, including psychosocial oncology, African American health disparities, relational aspects of chronic illness, women’s health, and qualitative methodologies. The authors used a staged, purposive, convenience sampling strategy to recruit a heterogeneous mix of African American women across different levels of income, education, and geographic location. Women who were recruited came from a prior randomized, controlled trial where they indicated an openness to participating in future research (Heiney, Million Underwood, et al., 2012). University of South Carolina and Palmetto Health institutional review boards approved the original study and an amendment for this follow-up investigation. All participants provided signed consent for contact and authorization permitting medical record review. The authors conducted the interviews in the homes of women residing in South Carolina who were originally treated in a private oncology practice.

The authors used a staged sampling and recruitment process from participants in the control arm (n = 93) of the original study to eliminate any possible influence that participation in the prior intervention may have had on treatment adherence. Thirty-eight potential participants were identified who met the eligibility criteria for this study: (a) residency in a specified geographic area, (b) had received radiation or chemotherapy treatment at a regional oncology treatment center, (c) no evidence of new or recurrent cancer, and (d) medical record available for review. The 38 charts were reviewed to determine adherence level because the authors’ original intent was to identify patients who had discontinued therapy or had major gaps in therapy. Surprisingly, no patients had discontinued treatment (either chemotherapy or radiation) and only a few patients had missed from one to three radiation therapy treatments. All patients completed all chemotherapy as prescribed.

The staged recruitment contact with potential participants was through a personal letter sent to the individual’s home address on letterhead that featured the logo from the prior study. A total of 19 invitation letters were sent in batches of four or five at a time about a month apart. This recruitment letter included instructions for leaving a phone message if the woman did not want any further contact from the researchers; however, no opt-out requests were made. The project recruiter contacted potential participants by phone several days after each mailing, explained the study, and offered to answer any questions. If the woman was interested in being interviewed, the recruiter determined the preferred location and time and scheduled an appointment. A total of 17 participants from the original study initially agreed to participate; one subsequently declined. Interviews were conducted from December 2011 to August 2012. Because of the positive participant response and the quality of the interview data and indications of thematic saturation, enrollment was discontinued at that time.

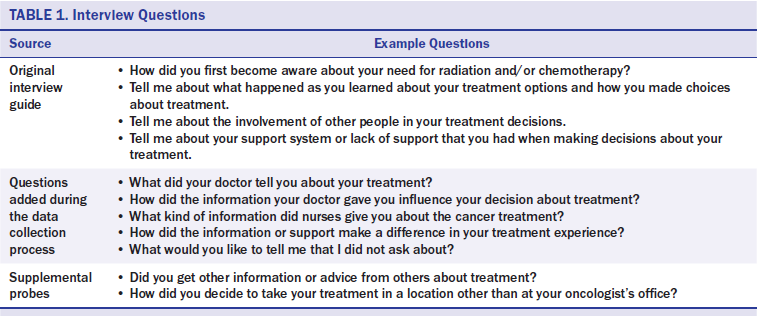

A semistructured, open-ended guide was developed specifically for this research. Given concurrent data collection and analysis, minor modifications were made after the initial interviews were analyzed (see Table 1). The two trained interviewers were African American women with experience in the community. One was doctorally prepared in nursing with an active clinical practice and the other was a public health researcher who conducted assessments during the original study (Heiney, Adams, Wells, Johnson, & King, 2012). The interviews ranged from 11–78 minutes (mean = 63.76, SD = 18.78). Following each session, the interviewer wrote field notes related to any salient aspects of the participant’s responses, demeanor, context, or setting, and also recorded any personal reflections on the process or content of the interview encounter (Patton, 2015). Professionals who were experienced with qualitative interview data transcribed the audiotapes; all identifying information was redacted from the transcripts. Based on previous research and clinical experience with this population of low socioeconomic status and low literacy, the authors did not conduct any postanalysis member checking (Oliver, Serovich, & Mason, 2005). For purposes of analysis, participants were identified by the research identification number. Pseudonyms were used when presenting the findings.

Participant Characteristics

The 16 African American women ranged in age from 27–72 years (SD = 8.85) and were, on average, 5.4 years post-breast cancer diagnosis prior to the interview (SD = 1.2, range = 3.8–7.6 years). Most of the participants (n = 9) were currently married. Seven had attended or completed high school, five had technical degrees, and four had advanced degrees. Reported income ranged from less than $20,000 (n = 7), $20,000–$39,999 (n = 3), and greater than $50,000 (n = 2). Occupations of the five who were currently employed were assembly line worker, small business owner, industrial worker, child support specialist, and administrator.

Data Analysis and Findings

The analytic approach was based on the principles and processes of feminist narrative research (Hilfinger Messias & DeJoseph, 2004, 2007; Riessman, 2008). Data analysis was an ongoing, iterative process involving multiple analysts’ reading and re-reading the data. Initially, each of the five analysts read and individually coded the same interview, identifying significant or salient phrases and words. The team subsequently met to review and discuss the content, range, commonalities, and distinctions within and across the initial open coding. Examples of initial codes include treatment plans, managing side effects, sources of support, and personal strategies.

As data collection proceeded, at least two investigators coded each interview transcript, concurrently expanding and refining the coding process and content. Following the initial coding of the 16 interviews, the authors identified and developed common themes across the interview data set (Hilfinger Messias & DeJoseph, 2004). In the following sections, the authors present representative data and interpretations of three themes related to treatment adherence: Embarking With Trust, Moving on Down the Road, and Being Actively Involved in Decision Making.

Embarking With Trust

In recounting their breast cancer diagnosis and treatment experiences, these African American women frequently reflected attitudes of acceptance and trust in providers’ expertise and recommendations. This acceptance often appeared to be more a reflection of acknowledgement of the inevitable. As Linda said, “Whatever it’s gonna be, it’s gonna be.” Rather than having actively questioned or inquired about treatment options, women embarked on the prescribed treatment with trust.

I know I have a good doctor, and I knew he would send me to where I needed to go. . . . He told me I had to go to the oncology treatment center. I went there, and they had things set up for me to have the radiation. So I said, “If this is going to help me.” I didn’t know much about it. (Ella)

Access to a specialized cancer treatment center offering coordinated treatment at the same site facilitated the women’s ability to comply with the prescribed treatment. Linda’s appreciation for the convenience of this type of one-stop service was representative.

I went to the doctor and they scheduled everything for me . . . and they [sat] me down and they talked to me and told me what all they were going to do, and [what treatment] I had to go and get.

Participants reported having both accepted and complied with the recommended breast cancer treatment. Minnie’s self-assessment reflected her sense of dutiful compliance. “So, I went for the treatment. I just had to accept what they were telling me.” Similarly, Daisy recounted, “I started the chemo because they told me I would need the chemo.” This willingness to comply with the prescribed treatment appeared to be associated with women’s inherent trust in their providers’ knowledge and expertise. Lissa noted she had no reason to question or second guess the prescribed treatment.

I didn’t question that really, because I knew that [the oncologist] had had other people to engage in figuring out what plan was best for me. But I trusted him. He was recommended by my surgeon. He had won several awards for the best oncologist in the [region]. I just did what the doctors and nurses told me to do.

These women did not report or recall having questioned or sought out information from other sources to validate the treatment recommendation and tended to attribute their survival to having been compliant with physicians’ treatment recommendations.

My mother, she died with breast cancer . . . [the surgeon] told me he wanted me to have the best treatment possible. He said that my mother was lost and he did not want to lose me, so that’s how I got to the [oncology treatment center]. . . . I’m convinced that that was the best thing that I could have [happened] to me. (Mae)

These narratives show little evidence of engaged, consensual treatment decision making with oncologists. Rather, most participants reported they had simply followed the doctor’s recommendation.

When I went to my oncologist, he explained how many treatments I would have. It wasn’t much of an option, because he basically told me the names of the drugs and why I would be taking these drugs and what they are trying to target. (Eddie)

Treatment adherence was a function of trust and deference to physicians’ authority rather than an actively engaged process in accordance with a woman’s expressed preferences or needs. Although taking ownership of her treatment plan, Frankie clearly acknowledged the impact of the oncologists’ recommendation.

I didn’t have to have chemo for that, but I had radiation. I didn’t have to have the radiation, but [the oncologist] said it would be better to have it. That was my decision, so I had that [radiation] . . . just, that’s what he thought should be done. He didn’t explain why.

In assuming the role of patients with breast cancer, women reported having accepted treatment recommendations without requesting options or explanations. Although some women reported their treatment recommendation had been the result of a team approach, they were not included in that team.

[The oncologist] told me that he would be getting with other oncologists, that he would not be the only one making the decision, as far as my treatment. So, it was five people that were intertwined with the decision of my treatment, which made me feel very good. So, when I came back in the office, he told me that he recommended six treatments of chemo, and that happened three weeks apart. (Lissa)

Although not having been actively engaged in treatment decision making, these African American breast cancer survivors did recognize and appreciate the health education they received. Daisy, who had a high school education, reported how her physician’s use of a metaphor was helpful in understanding why she needed treatment beyond surgery.

Dr. Jones said, “It’s just like a bag of apples, there can be one bad one in there and sometimes it sort of messes up the rest of them, and you have to clean the bag out first.” That’s why I had to take the treatment because, the cancer, [even though] they didn’t see any more of it, but to keep it from coming back.

Using more sophisticated medical terminology, Eddie, a college graduate, recalled the treatment rationale her oncologist provided.

He explained to me that I was staged at IIb and that I would be on a drug called [trastuzumab] to tackle the gene that was found during the staging.

Participants acknowledged and appreciated the role of the nurse navigators in providing assistance and information that helped them understand and follow their individual treatment plans.

I had a [nurse navigator] that, if I had any questions, she was right there for me. She gave me a notebook of anything that I might have questions on or anything and I didn’t understand, and I just read it, and that gave me a lot of information of what was going on. (Lydia)

Moving on Down the Road

This storyline reflected a personal resolve to continue moving on down the road during breast cancer treatment. Frankie’s comment was indicative of women’s resolve to just do what the physician recommended. “There wasn’t a lot of thought about it; whatever the [treatment team] said to do, I went in and did it.” Although not necessarily based on a clear understanding of the treatment rationale or plan, this resolve was a way to actively respond to a very personal threat.

Just because I . . . had cancer didn’t mean that I had to lay down and surrender to it. I gotta beat it, not let it beat me. Chemo was something I didn’t want to do, but [the oncologist] said it was a part of the treatment plan, so I did it. (Zora)

Not all the women had embraced their prescribed breast cancer treatment with resolve or zeal. Although less enthusiastic, Nancy was still compliant. “I know I needed the treatment. . . . [The knowledge] influenced me to go ahead and do what I had to do.” Etta described her initial reaction to the cancer diagnosis as “denial and a pity party” but later recognized the need to “go and do what had to be done.” Daisy reported “being upset” but remained committed to the prescribed treatment plan. “I was calm about it after I found out that I couldn’t change it.” Likewise, Ella recalled her personal resolve: “The cancer don’t have me. I was determined that [the cancer] wouldn’t take me.”

Another salient finding was that many women had assumed sole responsibility for the logistics required to adhere to the prescribed treatment plan (i.e., getting themselves to and from treatment locations). Diane reported very straightforwardly, “I just got off from work and went straight to radiation.” Shelley framed the personal responsibility of getting to and from the oncology center as complying with her doctor’s orders. “I drove myself there and back. . . . [The oncologist] would tell me to sit in the waiting room and make sure I had my thoughts collected right before I get on the road, and I did.” Rather than have her mobility restricted, Linda, whose cancer was in the right breast, drove “wheeling with my left hand.”

A Counter Narrative: Being Actively Involved in Decision Making

Although acceptance and adherence to the provider-recommended chemotherapy and radiation treatment plans was clearly a dominant narrative among these African American breast cancer survivors, some reported having made an active personal choice in relation to surgical treatment decisions. In analyzing these women’s narratives of their decision-making processes regarding how they had arrived at the decision to have a lumpectomy, the authors noted three common themes: (a) learning about surgical options from nurses and others, (b) listening to and trusting physicians’ explanations that mastectomy was not inevitable or necessarily the best choice, and (c) expressing an outright personal choice. Their engagement in surgical treatment decisions clearly contrasted with their trust and acceptance of providers’ recommendations for chemotherapy and radiation treatments. The African American women specifically reported having received helpful information from nurses about surgical recommendation options. Lydia recalled having sought out information from several sources.

The nurses gave me a lot of options that would better help me, whether I wanted to have [lumpectomy or mastectomy]. I didn’t want [mastectomy]. I just kept reading . . . and that’s how I decided that was the way I was going to go, and that’s what I wanted to do.

In making treatment decisions regarding breast surgery, several other participants also reported having received information and opinions from family members, friends, or acquaintances, which in some cases made complying with the doctor’s orders more complicated.

Several participants reported having been surprised to learn that mastectomy was not an inevitable consequence of having breast cancer and that they had the option to keep the affected breast. Leonora noted that, in discussing surgical treatment options, her provider challenged her assumption about the inevitability of having a mastectomy. “I was thinking, have [the mastectomy] done and get rid of it, but my doctor assured me that a lumpectomy would be a satisfactory way to go about it.” Five of the 16 participants specifically recalled having been given a choice regarding surgical options; all reported they had voiced their desire to have a lumpectomy to keep the breast.

[The surgeon] told me that I had a choice. He said, “You can either have the whole entire breast removed, or we can just remove the lump.” I don’t want [a mastectomy], but the doctor said, “I can’t tell [you] what to do exactly, but I will tell you this, most women in the past were just taking their breast off for no reason; they really didn’t have to take it off. It’s your choice.” I said, “I’ll go ahead and do the lumpectomy.” (Eddie)

However, that did not necessarily mean the decision was easy. Eddie also recalled the difficulty she had making a decision about mastectomy. “I didn’t know what to do because I [kept] hearing all these women say to just take my whole breast off.”

In contrast to their self-described acceptance of physician recommendations for radiation and chemotherapy, five women reported having informed a provider of their personal preference related to breast surgery. Shelly’s physician heeded her plea to “please save my breast if you can and if it’s not that much damage.” Similarly, Frankie was “pleased” when the doctor “told me he didn’t have to [remove the whole breast].” Lissa provided an explanation of the rationale for her not needing a mastectomy. “I feel confident that it didn’t go into my right breast. It just stayed defined to one area and just right here to the node area.” She also commented that, because medicine has come “far in 30, 40, 50 years,” mastectomy is no longer the only surgical option. This more knowledgeable and more active and engaged participation in treatment decisions contrasted with the same women’s reports of their trust in the physician’s chemotherapy and radiation treatment recommendations.

Two women reported having made another treatment-related decision regarding the location of radiation treatment facility; both made the choice based on proximity to their homes. Daisy chose where to have radiation.

[The oncologist] said I would have to take [radiation] every day for a month and my family didn’t want me driving to Smithville [for radiation]. So it was my choice to have it done here in Porterfield, where I could go [by] myself to the cancer place.

Shelly reported responding to the option to “either take radiation or chemotherapy.” In consultation with her family, her decision was based on location and accessibility to the radiation treatment site: “And I chose the radiation. [The oncologist] said either one was good. I just thought the radiation was better for me since I had to go and come by myself.”

These compelling narratives provide evidence of various processes the African American women engaged in as they made their own decisions regarding breast cancer treatment recommendations. Most did not report having actively participated in choosing or evaluating chemotherapy or radiation treatment options. They began their treatment journey with trust that the course recommended by the physician was one they should follow. As the diagnosis and need for treatment became a reality, they kept moving forward with the goal of completing treatment. In several cases, women reported being more personally assertive in voicing their personal preferences for lumpectomy, with the goal of breast preservation.

Discussion

African American women’s personal journeys in navigating breast cancer treatment recommendations are rarely depicted in the research literature. In this study, the authors incorporated a narrative analysis framework in eliciting and interpreting the recollected stories and reflections of breast cancer treatment among a diverse group of African American breast cancer survivors. Prior research suggests a high level of nonadherence to treatment in African American women (Albain et al., 2009). The current findings, which reflect the experiences and perspectives of African American breast cancer survivors in a specific geographic and cultural context, provide evidence that challenges this dominant assumption in the published literature studies (Gibson & Parker, 2003; Howard, Balneaves, & Bottorff, 2007; Kooken, Haase, & Russell, 2007).

In contrast to the findings from Torres, Dixon, and Richman (2016), the women in the current study did not perceive the physician’s age as a barrier to delivering quality care. In addition, the African American women in the current study reported greater reliance on providers instead of personal support systems when making treatment decisions than previously reported by Schubart, Farnan, and Kass (2015). Furthermore, the African American women interviewed did not identify spirituality or faith as a primary focus of reflections on treatment decision making. The current findings also indicated that these women did not appear to be active decision makers regarding chemotherapy and radiation treatment options. However, in accepting the recommended treatment plan, some did engage in an inner dialogue about how to get through treatment, resolving either to believe it was God’s plan or do what they had to do. They were receptive to information that enabled them to adopt and follow the recommended treatment plan but often relied on their own personal resources to get through treatment.

The authors embarked on this research to elicit patient stories about their breast cancer radiation and/or chemotherapy treatment experiences, particularly stories that described how they adhered to treatment. In contrast to patient care standards, which recommend shared treatment decision making between providers and patients, the authors found that the lack of shared decision making did not deter the participants from adhering to the prescribed treatment plan. In fact, it appeared to have contributed to enhancing their treatment adherence because of the trust they had in their providers’ knowledge and expertise in the field and their recognition that they did not have the requisite knowledge and expertise. Despite a wide range of personal responses, there was evidence across the participant sample of a similar shared philosophy of trusting their providers’ treatment recommendations as they kept moving on down the road to recovery.

Limitations

The study has several limitations, including sample size and lack of sample diversity in terms of adherent and nonadherent patients. Also, the study was conducted in one state in the southeastern United States and may not be transferable to other regions or ethnic groups.

Implications for Research and Practice

These findings make a major contribution to the field of interprofessional oncology care. Findings confirm the important role nurses and nurse navigators play in supporting patients throughout the treatment process. Implications include the need for nurses to provide ongoing information and support and assist patients in decisions about treatment and plans of care throughout the treatment and post-treatment trajectory. Patients in this study valued information differently. They also had different opinions about the timing of when they received information. Nurses should assess and reassess patient’s information needs and support as the patient progresses through cycles of treatment and different types of treatment.

Nurses, particularly nurse navigators who encounter patients soon after diagnosis, should determine patients’ perspective on treatment decisions and advocate for patients to be as active in the process as they want to be. Nurses should recognize that some patients are very comfortable in trusting the decision of the healthcare team, whereas others want to be more active participants in care planning. At the same time, nurses should reinforce the knowledge and skills of the care team so that the patient feels she can trust decisions that are made on her behalf.

Conclusion

Oncologists and nurse practitioners are highly educated professionals with very specialized knowledge; most oncologists in the United States are Caucasian and male. In view of the findings of the African American women’s trust in and deference to their oncologists, surgeons, nurse practitioners, and other healthcare providers, the authors recommend further investigation of the intersections of power and status differentials related to gender, race, class, and educational attainment underlying the patient–provider interactions related to cancer treatment recommendations (Weber, 2005; Weber & Parra-Medina, 2003). Other recommendations include conducting similar research on breast cancer treatment adherence among women of other ethnic or cultural groups in diverse geographic contexts, and exploring patients’ experiences and perspectives on the choice of newer oral chemotherapy treatment.

The authors gratefully acknowledge South Carolina Oncology Associates for facilitating the work on this project. The authors also acknowledge Susan Modugno, RN, BSN, OCN®, CCRC, for guidance on the chart review.

About the Author(s)

Heiney is the Dunn-Shealy professor of nursing, Hilfinger Messias is a professor, and Felder is an assistant professor, all in the College of Nursing, and Phelps is an associate clinical professor in the School of Medicine, all at the University of South Carolina; and Quinn is an assistant professor and the program director of graduate nursing in the College of Nursing and Public Health at South University, all in Columbia, SC. This research was funded by the ONS Foundation through an unrestricted grant. Heiney has previously consulted for and received honorarium from the Tree House Foundation. Quinn previously received payment from the University of South Carolina for writing and reviewing this article. Felder is currently funded by a Mentored Research Scientist Development Award to Promote Diversity from the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (K01CA193667). Heiney, Messias, Felder, and Quinn contributed to the conceptualization and design. Heiney and Quinn completed the data collection. Heiney provided statistical support. All of the authors provided the analysis and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Heiney can be reached at heineys@mailbox.sc.edu, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted April 2016. Accepted for publication June 2, 2016.