The Perceived Value of Online Cancer Resources Among Loved Ones of People With Cancer

Objectives: To examine the experiences with, opinions of, and reactions to online cancer information of loved ones of people with cancer.

Sample & Setting: 10 loved ones of people with cancer recruited from a pool of participants who completed a survey about cancer website experiences.

Methods & Variables: Qualitative, semistructured interview questions concerned the perceived value of and reactions to online cancer information. Responses were analyzed using a grounded theory approach.

Results: Cancer websites play an important role, often serving as a first source of information. All participants said the Internet was helpful but could lead to negative emotions or misinformation. Future efforts should seek to mitigate the negative effects associated with the use of such websites.

Implications for Nursing: Healthcare providers should direct people with cancer and their loved ones to reputable websites that provide support in conjunction with information, or work toward developing their own in-depth resources.

Jump to a section

Loved ones of people with cancer are vulnerable, demonstrating lower quality of life and higher anxiety than those actually diagnosed with the disease (Kuenzler, Hodgkinson, Zindel, Bargetzi, & Znoj, 2011). Many loved ones receive less information about cancer than they need (Friðriksdóttir et al., 2011), which is concerning because they are often relied on to provide cancer information to the patient (Nagler et al., 2010). This lack of information, coupled with feelings of anxiety, may lead loved ones to seek out cancer information online (Kinnane & Milne, 2010), with research finding that 77% of loved ones had viewed online cancer information at least once (Lauckner, 2016). Among Internet-using caregivers for individuals with serious illness, 84% sought online health information, and 52% said this information helped them to cope with stress (Fox, Duggan, & Purcell, 2013). Seeking health information online has also been found to empower individuals to make healthcare decisions (Seçkin, 2010).

However, viewing online cancer information may also cause distress for loved ones (Klemm et al., 2003) as a result of seeing frightening content (Han & Belcher, 2001). Research in this area with patients’ loved ones is scarce, but a study of parents of children with cancer found that many avoided the Internet because of fear of what they might find, uncertainty over information accuracy, and the potential for information overload (Gage & Panagakis, 2012). In addition, an observational study of college students (N = 34) found that 44% of respondents felt confused when they last searched for health information, 26% felt frustrated, and 15% felt frightened (Buhi, Daley, Fuhrmann, & Smith, 2009). The literature suggests that loved ones of people with cancer will likely seek out online information about cancer, but the usefulness and effects of doing so are unclear. Using interviews with loved ones of people with cancer, this exploratory study used a grounded theory framework (Glaser, 1992) to examine experiences with, opinions of, and reactions to online cancer information.

Methods

Design and Participants

The results presented in this article are based on the second phase of a two-part mixed-methods study. The first phase involved a one-time quantitative survey that inquired about participants’ (N = 191) loved ones with cancer, as well as their frequency of viewing online cancer information and their most recent information-seeking experience (Lauckner, 2016). The survey was developed based on previous research and the author’s prior content analyses of cancer websites. Scales developed for the study had adequate internal reliability, and pretesting of the survey helped to address issues of clarity and cohesiveness. To ensure salience and to increase accuracy of recall, inclusion criteria required that participants had a loved one diagnosed with cancer in the previous year or self-identified as a cancer caregiver. There were no exclusion criteria. Participants were recruited over three months using convenience sampling from discussion boards on cancer- and caregiver-centered websites, a health communication research Listserv, social media posts, Listservs of cancer organizations in the Midwest, and a Relay for Life® event.

Phase two of this research consisted of a qualitative follow-up interview conducted with individuals who completed the initial survey and indicated their interest in participating in the interview by providing their email address. The final sample for this interview consisted of 10 participants who were available to speak with the author. The results and procedures described in the remainder of this article refer to these 10 individuals and their interview experiences.

Interview Protocol

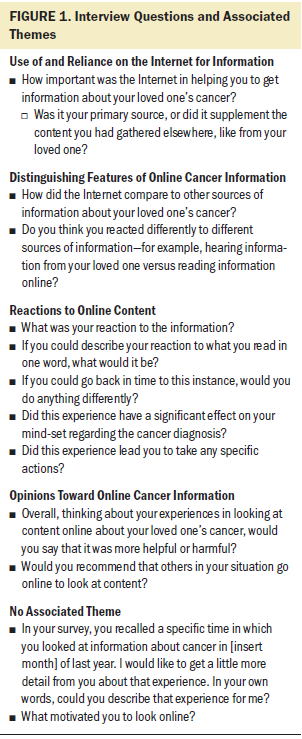

Participants who volunteered to complete the interview were emailed and encouraged to schedule a telephone interview with the author within three months of survey completion. The author read a consent form to the participant and obtained verbal consent to participate and be audio recorded. Using a semistructured protocol, participants responded to the questions in Figure 1, with occasional follow-up questions added. This protocol was developed based on the existing literature and was refined after an assessment of survey responses to probe findings.

Analysis

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. Responses were grouped according to interview prompt, and a grounded, qualitative content analytic approach (Glaser, 1992) was used to analyze responses on a question-by-question basis. The author analyzed transcripts for recurring themes that described common experiences and for interesting deviations from the norm. A panel of health communication and eHealth scholars, chosen for their experience in the subject area, reviewed the results for clarity.

Results

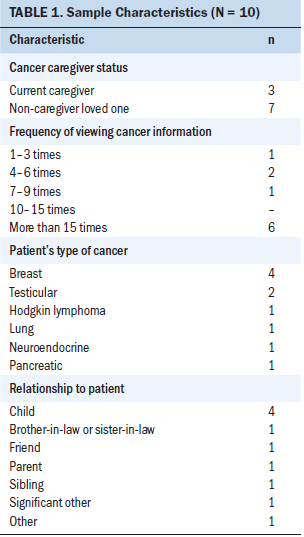

The characteristics of the sample are listed in Table 1. All participants were Caucasian women, with a mean age of 35.9 years (SD = 14.48). Themes associated with participants’ interview responses are presented.

Use of and Reliance on the Internet for Information

Several participants indicated that the Internet was their primary cancer information source. One participant said it was “definitely the primary source, because I didn’t really get that much information from health providers.” However, others said that the Internet was supplementary to healthcare provider–given information, and some stated that its role had changed over time. One participant said, “Initially [the Internet] was my primary source, before we actually had an appointment with the oncologist. . . . Then it became supplemental to the oncologist.” This initial dependence on the Internet was reported by many participants who said that the first place they sought information was online.

Distinguishing Features of Online Cancer Information

Many participants discussed differences between Internet and in-person sources. Several remarked that online information was more detailed and varied, as reflected in the following statement: “The only other place I got information was from healthcare providers . . . and that was all very generic and quite limited . . . whereas the Internet provided scientific information as well as practical information.” This mention of practical information suggests that more support-based content is available online. The Internet provided access to “different stories” and to information about “how to cope.” These responses imply that healthcare providers may stick to basic facts when they communicate with patients and loved ones, which is why many end up going online to fulfill their information and support needs.

Reactions to Online Content

A few participants said they felt more anxious when getting cancer information online compared to receiving it in a face-to-face format, either because of the volume of online information or the lack of a “human” element.

The nature of medical [information] is going to be, “Here are the facts about what we know about this particular medical issue.” . . . It’s just like a doctor who doesn’t have good bedside manner. . . . It’s a little scary to hear when they don’t filter it through the “Oh my God, this person’s terrified” kind of filter.

However, this was not a universal experience. Some participants said that, because of the situation, they were emotional no matter how they obtained information. Others preferred to go online because they could absorb information at their own pace without having to hide their reaction.

After viewing information, several participants felt sadness or fear. However, many also felt reassured or “cautiously optimistic.” This suggests that no universal response exists to reading online cancer information, but that individuals feel a mix of positive and negative emotions. This also likely varies depending on the nature of the diagnosis.

Opinions Toward Online Cancer Information

All participants said they would not do anything differently in terms of viewing online cancer information. Many remarked that, despite encountering information that induced anxiety, it was worth it to be informed. One participant stated, “Some of the information was hard to read, but I’m glad I did because I feel like it prepared me more.” Every participant recommended that others in their situation go online to find cancer information, but most added a caveat: Stick to reputable websites.

All participants said that the Internet was more helpful than harmful for finding information, although many recognized that it could be detrimental for those who are anxious about health issues or cannot judge the trustworthiness of websites. The Internet was primarily described as helpful because of its valuable information.

My dad died of bladder cancer in ’96. The only information I knew about my dad’s cancer was what I got from his physician. The Internet has provided me with much more detailed information about diagnoses and treatment and options and where to go and how to deal with side effects and what to expect . . . so I would say it’s been incredibly helpful.

Discussion

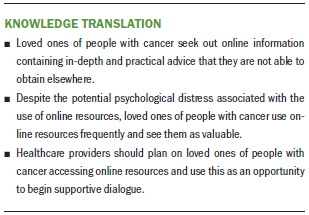

This research points to the pivotal role of websites in meeting the needs of loved ones of people with cancer. Most participants stated that the Internet was their primary and initial source of cancer information, whereas others said it played an important supplementary role. This supports previous research that has found that many parents of children with cancer used the Internet as a supplementary source after receiving the initial diagnosis from healthcare providers (Kilicarslan-Toruner & Akgun-Citak, 2013). Given that all the participants in the current study stated that the Internet was more helpful than harmful, websites appear to be valuable tools for this population.

Although some individuals felt anxious about what they read online, as has been determined previously (Klemm et al., 2003), they shared a sense that knowledge is power and were glad to educate themselves. Research has suggested that these loved ones then use this knowledge to inform treatment decisions and communicate with healthcare providers (Kinnane & Milne, 2010). Future research could explore methods of reducing distress for online information seekers, such as communicating in simple language, allowing opportunities to ask questions, and providing emotional support (Parker et al., 2001).

Limitations

This study had a small sample made up of Caucasian women. Consequently, the results may not reflect relevant cultural or gender-based experiences. Participants had a variety of cancer experiences, which improves generalizability, but this may have limited the emergence of themes according to specific cancer types or participant roles. Future research is planned to build on these preliminary findings with a larger and more diverse sample.

Implications for Nursing

Because loved ones of people with cancer appear to be determined to use online resources, nurses could guide them toward reputable and supportive websites to prevent negative experiences, such as www.cancer.gov (National Cancer Institute) or www.cancer.org (American Cancer Society). Healthcare providers could also evaluate eHealth literacy among loved ones to determine if they need support in navigating online materials (Lixin, Tatum, Greene, & Chen, 2017). In addition, providers could develop their own websites for loved ones or add content to their existing sites that combine potentially alarming cancer facts (e.g., mortality statistics) with supportive language to enhance coping. Future nursing research could seek to explore methods of communicating about online information-seeking in face-to-face settings to better address this behavior.

Conclusion

This research demonstrates the importance of online resources for loved ones of people with cancer. They are a valued source of information, despite the potential negative emotions that may result from reading such websites. Offering guidance and support regarding online cancer resources could have important benefits for patients and their loved ones in regard to coping with the illness and its treatment.

About the Author(s)

Carolyn Lauckner, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Health Promotion and Behavior at the University of Georgia in Athens. No financial relationships to disclose. Lauckner can be reached at clauck@uga.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted July 2017. Accepted December 8, 2017.)

References

Buhi, E.R., Daley, E.M., Fuhrmann, H.J., & Smith, S.A. (2009). An observational study of how young people search for online sexual health information. Journal of American College Health, 58, 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448480903221236

Fox, S., Duggan, M., & Purcell, K. (2013, June 20). Family caregivers are wired for health. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/2013/06/20/family-caregivers-are-wired-for-h…

Friðriksdóttir, N., Sævarsdóttir, T., Halfdánardóttir, S.Í., Jónsdóttir, A., Magnúsdóttir, H., Ólafsdóttir, K.L., . . . Gunnarsdóttir, S. (2011). Family members of cancer patients: Needs, quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression. Acta Oncologica, 50, 252–258. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2010.529821

Gage, E.A., & Panagakis, C. (2012). The devil you know: Parents seeking information online for paediatric cancer. Sociology of Health and Illness, 34, 444–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01386.x

Glaser, B.G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emergence vs. forcing. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Han, H.R., & Belcher, A.E. (2001). Computer-mediated support group use among parents of children with cancer—An exploratory study. Computers in Nursing, 19, 27–33.

Kilicarslan-Toruner, E., & Akgun-Citak, E. (2013). Information-seeking behaviours and decision-making process of parents of children with cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17, 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2012.03.001

Kinnane, N.A., & Milne, D.J. (2010). The role of the Internet in supporting and informing carers of people with cancer: A literature review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 18, 1123–1136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0863-4

Klemm, P., Bunnell, D., Cullen, M., Soneji, R., Gibbons, P., & Holecek, A. (2003). Online cancer support groups: A review of the research literature. Computers, Informatics, Nursing, 21, 136–142.

Kuenzler, A., Hodgkinson, K., Zindel, A., Bargetzi, M., & Znoj, H.J. (2011). Who cares, who bears, who benefits? Female spouses vicariously carry the burden after cancer diagnosis. Psychology and Health, 26, 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903418877

Lauckner, C. (2016). The emotions and action tendencies associated with viewing online cancer information among patients’ loved ones. Journal of Health Psychology, 21, 2525–2537. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315581063

Lixin, S., Tatum, K., Greene, G., & Chen, R.C. (2017). eHealth literacy and partner involvement in treatment decision making for men with newly diagnosed localized prostate cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 44, 225–233.

Nagler, R.H., Romantan, A., Kelly, B.J., Stevens, R.S., Gray, S.W., Hull, S.J., . . . Hornik, R.C. (2010). How do cancer patients navigate the public information environment? Understanding patterns and motivations for movement among information sources. Journal of Cancer Education, 25, 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-010-0054-5

Parker, P.A., Baile, W.F., de Moor, C., Lenzi, R., Kudelka, A.P., & Cohen, L. (2001). Breaking bad news about cancer: Patients’ preferences for communication. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 19, 2049–2056. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2001.19.7.2049

Seçkin, G. (2010). Cyber patients surfing the medical web: Computer-mediated medical knowledge and perceived benefits. Computers in Human Behavior, 26, 1694–1700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.018