Perceptions of Distress in Women With Ovarian Cancer

Purpose/Objectives: To explore women’s experience of distress by asking “What do women with ovarian cancer want their spouse or significant other, family, friends, and healthcare providers to know about their experience of distress during diagnosis and treatment?”

Research Approach: Modified Glaserian grounded theory.

Setting: An urban setting in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States.

Participants: 12 women, aged 21–71 years, diagnosed with and treated for ovarian cancer.

Methodologic Approach: Constant comparative analysis of data obtained by audio recorded interviews.

Findings: Although individual experiences differed, abstraction and conceptualization of the data supported a theory of existential assault. Participants found that the diagnosis was shocking and came “out of the blue like lightning.” Their responses included seeking the best physician and treatment available, described as “no stone left unturned.” Information about the disease was welcomed and unwelcomed as they shared the experience of “knowing what I don’t want to know and not knowing what I want to know,” and then had the added experience of sharing that information with those in their social network. Interpersonal interactions were described as “watching you watching me—we are both afraid,” and “talking yet not talking about death,” resulting in relationship changes and the realization that “now I have to take care of me.”

Conclusions: Participants experienced diagnosis with and treatment for ovarian cancer as an existential assault that, with the potential for an early death, affected the individual and her relationships.

Interpretation: Previous studies have suggested that women diagnosed with and treated for ovarian cancer experience distress. This study reports women’s perceptions of their own distress.

Jump to a section

The diagnosis of ovarian cancer is unexpected and devastating for women and their families. Diagnosis may be complicated and delayed with the initial symptoms attributed to nonspecific physical and emotional conditions, such as fatigue, gastrointestinal and genitourinary alterations, menstrual irregularities, depression, and stress (Goff, Mandel, Muntz, & Melancon, 2000). Only 15% of women are diagnosed at an early stage when ovarian cancer is most responsive to treatment; 61% are diagnosed when the cancer is distant or metastasized. The relative five-year survival rate for all stages of ovarian cancer is 46%. Ovarian cancer is the fifth-leading cause of cancer-related death among women, but it accounts for only 5% of all cancer diagnoses in women in the United States (American Cancer Society, 2014).

Background and Significance

Results of research have suggested that women with ovarian cancer experience distress at multiple time points in the disease trajectory (Cain et al., 1983; Dawson, 1993; Lobchuk & Bokhari, 2008; Matulonis et al., 2008; Norton et al., 2004, 2005; Portenoy, Kornblith, et al., 1994; Portenoy, Thaler, et al., 1994). Qualitative studies have reported women’s perspectives related to ovarian cancer diagnoses (Ferrell et al., 2005; Ferrell, Smith, Cullinane, & Melancon, 2003a, 2003b; Fitch, Deane, Howell, & Gray, 2002; Ponto, Ellington, Mellon, & Beck, 2010; Power, Brown, & Ritvo, 2008; Reb, 2007; Schulman-Green et al., 2012), including the challenges of late diagnosis and the treatment regimen (Ferrell et al., 2003b), communication difficulties with healthcare providers (Fitch et al., 2002), and concerns about the effect of the diagnosis on their loved ones (Ferrell, Smith, Ervin, Itano, & Melancon, 2003). In a systematic literature review, Arden-Close, Gidron, and Moss-Morris (2008) examined psychological distress, specifically anxiety and depression, and concluded that emotional distress was a part of the experience for many women with ovarian cancer, particularly younger women and women diagnosed at a later stage.

The diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer may initiate profound effects to physiological, psychological, psychosocial, and spiritual domains in affected women and their families. In studies of women with ovarian cancer, distress was infrequently defined and often ambiguously interpreted and measured as anxiety and depression. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s ([NCCN’s], 2014) definition of distress was rarely used in studies with this population. To better understand and develop supportive interventions to decrease distress, considering the experience from the perspective of women is important. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore women’s experience of distress by asking, “What do women with ovarian cancer want their spouse or significant other, family, friends, and healthcare providers to know about their experience of distress during diagnosis and treatment?”

Methods

This study, approved by the institutional review boards of Virginia Commonwealth University and Bon Secours Richmond Health System, used Glaserian grounded theory methodology (Glaser, 1965, 1992, 2005, 2012; Glaser & Strauss, 1967) with modifications to identify a theory that was reflected in and emerged from the data. Modifications included an initial literature review of distress in women with ovarian cancer, the use of an interview guide inclusive of a research question, and convenience rather than theoretical sampling.

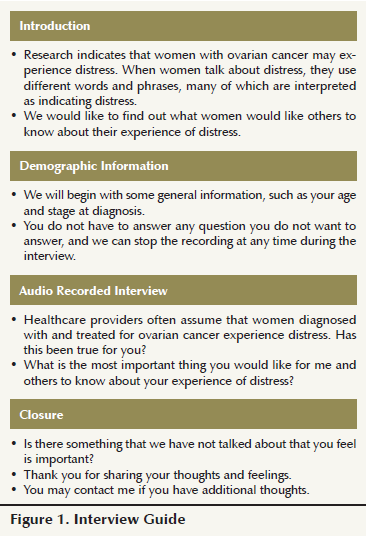

Participants were recruited from gynecologic oncology offices located in the central Virginia area, as well as from an email contact list for an oncology support group. Women were included if they had been diagnosed and treated for ovarian cancer, spoke English, and were aged 18 years or older. Twelve of 15 individuals who responded to the recruitment brochures met criteria, consented, were enrolled into the study, and completed the interview process. Interviews occurred from February to August 2013 in a location chosen by the participant (i.e., a library, medical interview room, or coffee shop). An interview guide was used to begin and end the conversation (see Figure 1). The guide provided an initial structure to the data collection; however, as the interviews progressed, participants voluntarily shared significant content without requiring interview prompts.

Data Collection and Analysis

Constant comparative method provided for concurrent data collection and analysis. The professionally transcribed interviews were converted to Microsoft Word® documents that were then compared with the audio recording for accuracy and for nonverbal contributions, such as tapping on the table, pauses, or variations in tone of voice. Coding was done by the investigator with peer review of interviews one, five, and nine to evaluate accuracy, potential bias, and consistency in the process. Memos were compiled throughout the data collection and analysis process. Substantive line-by-line coding, followed by abstraction and conceptualization, were used to develop theoretical codes that were hand sorted along with the memos into groups of like variables and then further grouped into subcategories. The investigator constantly returned to the data, reflecting on the process, memoing, and bracketing so as to capture all aspects of the grounded theory developmental process. Systematic record keeping and reflective journaling contributed to the rigor of this research study.

The audio recorded interviews provided rich, candid details of the participants’ diagnoses and treatment as well as the emotional impact on themselves and those around them. Data contributed by the 12 women provided sufficient content for constant comparative analysis with saturation (i.e., no new categories or theoretical codes emerging), beginning with interview 10 and confirmed throughout interviews 11 and 12.

Findings

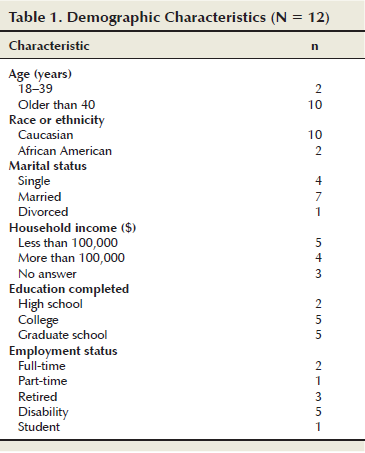

Findings were grounded in the data and reflected the experience of participants, who ranged in age from 21 to 71 years, with a wide variety of diagnostic stages and treatment (see Table 1).  Six common themes or subcategories emerged across all the interviews and resulted in a conceptualization of the experience as an existential assault. Participants spoke freely and, at times, paused, hesitated, and wiped away a tear, which indicated the depth of their emotional experience. One stated, “And we felt like this death sentence had been, you know, uh, you know, proclaimed.” A husband’s reported first response was, “I don’t want to lose you.” A dream shared by another illustrated feelings of isolation from those around her and the threat of death.

Six common themes or subcategories emerged across all the interviews and resulted in a conceptualization of the experience as an existential assault. Participants spoke freely and, at times, paused, hesitated, and wiped away a tear, which indicated the depth of their emotional experience. One stated, “And we felt like this death sentence had been, you know, uh, you know, proclaimed.” A husband’s reported first response was, “I don’t want to lose you.” A dream shared by another illustrated feelings of isolation from those around her and the threat of death.

I’m sitting on the beach and I’m reading a book. . . . I am the only person on the beach. . . . I put my book down and I walk up to the edge of the waves. . . . I get far enough out that I can lay on my back and float. . . . The ocean is just rocking me. . . . After a little while I decide to turn around and tread water. . . . I look back at the beach and where it had been unpopulated . . . everybody I’ve ever known my whole life is on the beach. Then the scary part happens. There’s a fin . . . another fin . . . the fins start circling around me. I start waving my arms at all the people on the beach . . . [they] just smile and wave back at me and, of course, the fins are circling, and so I wave more frantically; the sharks are circling . . . death is circling . . . they don’t get it. . . . Then I wake up in a cold sweat, and that’s what it feels like to have cancer . . . everybody is that close going on with their lives . . . they can’t know what it feels like because they’re on the beach and it’s not happening to them.

Past experiences with death were included in all interviews. Several participants had “almost died” during the prediagnosis or treatment phase. Two had lost their mothers to cancer, whereas others had lost close family members. They had heard horror stories, knew that survivors of ovarian cancer were rare, and were sometimes careful to limit their own exposure to harsh realities. Although some women engaged in extensive personal research and found comfort in the process, others limited their exposure to too much information and found comfort and hope in the uncertainties that accompanied the diagnosis and treatment. Despite a small sample size, differences were noted when age-appropriate developmental tasks were expressed by the participants. For example, the two youngest women mentioned concerns about reproductive issues and one of the older participants discussed the items on her “bucket list.”

Through constant comparison analysis, abstraction, and conceptualization of the data, the beginning of a theory has emerged. Participants related the common experience of an existential assault with six subcategories: (a) Out of the Blue Like Lightning; (b) No Stone Left Unturned; (c) Knowing What I Don’t Want to Know and Not Knowing What I Want to Know; (d) Watching You, Watching Me—We Are Both Afraid; (e) Talking Yet Not Talking About Death; and (f) Now I Have to Take Care of Me.

Out of the Blue Like Lightning

Diagnosis was shocking and unexpected, accompanied by uncharacteristically rapid medical attention with multiple tests, referrals, immediate surgery, and, at times, frank discussions of options and plans of care. The experience was incongruent with personal perspectives of a healthy self. One stated, “I’m healthy except for the part where you tell me I’m dying.” Nonverbal cues from healthcare professionals, such as the urgency of the medical response, tone of voice, facial expressions, and avoidance of eye contact, all communicated the seriousness of the illness. One participant recalled being given the diagnosis via telephone, and mentioned, “I could tell by his voice that it was serious.”

Contributing to the shock of the experience was the knowledge that their initial symptoms or concerns were incorrectly diagnosed or dismissed. Even those who knew something was wrong and had seen other doctors found the diagnosis of ovarian cancer to be shocking. Several related that a time lapse occurred between when they heard the diagnosis and when they were able to understand the implications, with one stating, “It didn’t register so [the physician] repeated it.”

No Stone Left Unturned

The focus shifted quickly to identifying treatment options. Going for a second, third, or multiple opinions; joining clinical trials; and researching on the Internet was an effort made by participants to find the right physician and the right treatment. One chose to seek a second opinion when she felt the physician “had given up on me.” Knowing that they were doing everything that could be done was comforting for the participant and her family. The comparative lack of information, resources, and media attention for ovarian cancer, compared to breast cancer, created concern for some that they were not getting the best information and latest treatments available. When medical resources were exhausted, these participants were willing to consider unconventional alternatives and sought treatments at different hospitals with different physicians and looked for information on Internet sites. One reflected, “I’ve not left any stones unturned that I know of.”

Knowing What I Don’t Want to Know and Not Knowing What I Want to Know

All participants were aware of the seriousness of the diagnosis, but did not always know how it would affect their lives. One succinctly stated, “I may not be here in five years.” Another poignantly asked, “Do I live like I’m going to live or like I’m going to die?” Diagnosed before age 50, she had already experienced a recurrence and related her dilemma of leasing or buying a car, renting or buying a home, and choosing to go on her dream vacation or investing her finances for retirement. Daily routines and relationships were affected by the seriousness of the diagnosis. Life was now experienced in three- or six-month increments waiting for the results of the latest test, hoping for remission and not recurrence. This continual state of uncertainty created ambiguity on personal and relationship levels. One woman said, “I don’t always know what I need or want . . . sometimes I need time alone to think . . . sometimes I need distraction.”

The need to know the truth about the diagnosis existed alongside the need to retain hope for remission or even cure. One participant wondered, “How do I live with knowing I’m never really going to be okay? I mean, you’re okay today, but you live with that threat. It’s like living with a cloud over your head, you know?” Paradoxically, the uncertainty brought hope and stress described as an “emotional roller coaster . . . never knowing if you are going to get better or worse.” Even good news, at times, contributed to feelings of stress because of the awareness that eventually the news would not be good: “I’m wondering when the next shoe will drop.” One participant expressed the challenge of existing between the certainties and uncertainties.

So you have this terrible disease that’s probably going to shorten your life and shorten it a lot. . . . And so there’s this incredible pressure on all of your decisions about now that you know, you know how valuable time is. So you . . . your decisions . . . are supercharged with meaning and pressure.

In general, participants wanted to focus on positive thoughts and avoid negative ones. One, with graduate education, shared that she knew it was superstitious and not rational, but felt that worry seemed to prevent bad things from happening. “I worried about breast cancer, but didn’t get it, but I never worried about ovarian cancer, and I got it.” The overall preference was to “hang on to hope” with a degree of fear that if they talked about death, it made it more real. Another participant reflected on the dilemma faced by physicians.

know doctors don’t want to give people false hope because that’s just as bad . . . and I don’t know how you balance that with . . . is it better to know that there’s . . . okay, you have three months to live and deal with that, um, or give people, you know, hope and say, “We’re not sure. We don’t know.” I don’t know which is worse, to say, “I don’t know,” or say, “Okay, this is what you have.”

Watching You Watching Me—We Are Both Afraid

The impact on the participants’ social network introduced additional complexity. One spoke about the times she would observe her family looking at her. “You know, it’s like sometimes I’d catch them and they’d look at me like, you know . . . and I’m thinking . . . ‘I’m not dead.’” Several realized that the reactions of others were rooted in their own fears of death. For example, one participant stated,

I’ve learned . . . when people encounter people with cancer, they start processing their own mortality. My son’s girlfriend wouldn’t let him microwave food because she was afraid they would get cancer. Everything, suddenly everything was about them getting cancer. . . . And suddenly they were going for all this testing and all. And I’m sitting there thinking [pause], “I’m the one with the cancer” [laughs].

Women experienced intensified distress related to witnessing the effect of the diagnosis on those they loved. For example, one participant noted that the “hardest part is the pain this causes those I love.” All were concerned for those around them and found it hard to watch others suffer because of their illness. The negative effects the diagnosis had on others led participants to withhold information to prevent bringing pain to or increasing fear for their loved ones. Even those with positive, supportive relationships found it necessary to gauge their conversations based on the ability of those around them to respond. Not only were they dealing with their own fears and questions, they were also dealing with the fears and questions of those around them. “They can’t do anything about it anyway, and then I would have to take care of them” was the way one participant explained her preference for not sharing information with her husband and children about her advanced and recurrent cancer. She found it difficult and stressful to respond to social courtesies that required her to provide updates in the midst of uncertainty. She was able to continue her work responsibilities by not sharing her personal experiences and expressed that “a smile hides much.”

Interactions with healthcare providers were significant because participants not only gathered information about the diagnosis and treatment, but also observed the provider’s verbal and nonverbal cues.

We watch your every move. So if you are giving an exam and you go, “Hmm,” that has tremendous meaning for me. When you all walk in the room together with lots of paperwork, I know what that means before you open your mouth. Like, so you have to be really aware. I know you’re just getting through your day, and you’ve got messages and people waiting on you, and your spouse is calling you, and it’s just, you’re just working. . . . But remember this is the most important thing that has ever happened to your patients, and we watch your everything. And then we go home and we think about it a lot. We try to figure out what you didn’t tell us. So you need to be really careful about that, to not send unintended messages, or if you are sending a subtle message to be aware that you’re doing that too.

Talking Yet Not Talking About Death

The certainties and uncertainties of death were both spoken and unspoken, sometimes identified by what was not said, by humorous comments, through nonverbal cues, such as volume or tone changes, hesitancies, and the struggle to find the right words. One cautiously verbalized, “I’m going to . . . you know. . . . This is it.” Another credited her ever-present sense of humor with prolonging her life, indicating that others would die sooner “because of their attitude.” Demonstrating a preference to avoid conversations about death, one participant, referring to Internet chat websites, noted, “When women are talking about things like that, I go to another subject because it doesn’t apply to me.” However, this same participant shared freely the story of her sister’s recent death and her own personal measures to find treatments despite being told by physicians that no more treatments were available. Another observed that “almost every day someone dies on those bulletin boards, you know. ‘So-and-so earned her wings.’ . . . It happens almost every single day.” Another noted, “Friends can say the wrong thing unintentionally.” She had learned to answer the ever-present social courtesy of, “How are you?” with, “I’m hanging in there.” This tactic allowed for varying depths of conversation depending on her or the other person’s readiness for honesty.

The ability to talk about death depended on both the personal internal readiness of the participant and also on the response and readiness of those around her. This created a complex dynamic because, ultimately, every conversation postdiagnosis was within the context of ovarian cancer. The readiness of others to approach difficult conversations influenced the intimacy of relationships. Family members or friends who were not able to adjust to the new normal were sometimes relegated to a more distant social position. These people often were identified as actually adding to the measure of stress experienced. Participants found it easier to minimize contact with those individuals. One reflected on the intricacies.

Every time I discuss it, I have to hand him death again. . . . And so I’m stuck between do I not share or do I hand him death again. . . . It’s a big responsibility [pause]. There are some people around you that can’t go there. . . . They can’t, you can’t have a real conversation with them about dying, about the path there and what you’re afraid of and what you’re okay with and how you want . . . they just can’t. They’re not ready, they’re not there, and I think it’s helpful to sort of understand that some people can and some people can’t.

One participant had already planned her own funeral, which was “by invitation only.” Her funeral arrangements were discussed with five identified close friends because her family was not ready to have such frank conversations. During the interview, she quickly changed the subject to her personal action plan for finding the best physicians and treatments, demonstrating her own tenuous ability to talk about her own death. Another, who was close to the five-year survival date and had just learned of her recurrence, said with emphasis. “I don’t allow anyone to take my hope.” Her determination to avoid any “negativity” was reflected in her statement.

But you just give people grace because they don’t know what to say and they . . . they’re nervous about it. I’m not nervous about it; they’re nervous about it. My family can get nervous about it, so they say things and ask me things and I’ll say, “Today I’m whole, so let’s live in the day. Today I’m whole. Today I’m well.” Let’s live today, you know. But we do have, um, my daughter and myself, you know when we ride in the car now, which we didn’t do before, we just hold hands . . . you know, so I’m okay with that, but today I’m whole; I’m well.

Other participants who commented on the topic chose to put their lives in perspective and reflected, “I’ve had a good life” and, “Everyone has to die someday.”

Now I Have to Take Care of Me

Over time, the participants discovered the need to focus on self-care. This self-advocacy was reflected in the comment, “It’s either me in control or cancer in control.” Speaking about attending a support group, one explained her decision not to attend by stating, “This is the time for me, and I can’t be me if I’m a part of we.” Reflecting on the changes in her life, another noted that “I took better care of others but now I am taking care of myself.” And another said, “So I would spend . . . I believe I would spend more time taking care of them to get them over what I’m going through than me, and I want to be focused on me [fingers pound on table].” Coming to the realization that “now I have to take care of me” was a source of tension and of discomfort because many of the women had been in the caretaker role and responsible for maintaining connections within the family. Often, no one else was prepared to assume those informal duties.

Participants employed a variety of methods for taking care of themselves. One stressed, “It is important for you to know your doctor and for your doctor to know you,” and she had changed physicians to find one who contributed positively to her emotional as well as physical well-being. Surrounding themselves with positive influences and controlling stress was part of their personal action plans. For some this included eliminating negative relationships described as “getting rid of those who had given up on me” or even quitting a stressful job. Having future plans, improving nutrition, and getting a massage were mentioned as self-care activities. The Internet provided options that several explored, particularly as the success of traditional medical intervention waned. Clinical trials offered hope and provided the opportunity to help someone else if they did not personally benefit. Each participant mentioned prayer or meditation even if religion was not part of their value system. One stated,

Um . . . What do they say, “There’s no atheists in foxholes.” . . . I’m surprised that there are any, ah, um, atheists in cancer. And I don’t know that they go to God, you know, depending on where you are beforehand. And I have not been a religious person in a long, long, long time and you know I started out from a place of, um . . . agnosticism, like I have no idea. . . . But there are definitely some moments where you might shoot a prayer out to whoever, whatever, however, and make the deals that you make.

This new focus on self was beneficial because participants needed to advocate for themselves and pursue additional, even experimental, treatments.

Discussion

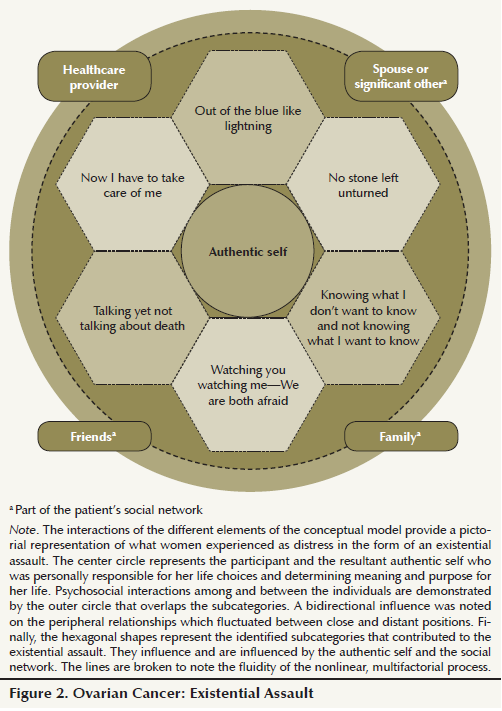

The purpose of grounded theory method is to identify a theory based on substantive data that helps others better understand phenomena. In this study, the core variable that emerged across all interviews was the experience of existential assault. An existential assault is an unanticipated threat of death that alters normal life expectations. Participants described an assault on their very existence. The diagnosis altered each participant’s future as they considered the potential for an untimely death. The conceptual model that resulted from this grounded theory study is multifactorial and dynamic, beginning with the diagnosis of ovarian cancer for a woman (see Figure 2). The subcategories are fluid and interrelated and do not stand in isolation of one another but interact and combine to lead to the emergence of the authentic self. The authentic self, as extrapolated from analysis of data collected, is an individual who is self-aware and assumes personal responsibility for life choices. In response to the perceived existential assault, study participants expressed a realization that they needed to be responsible for choices in a way that brought a sense of meaning and purpose to their lives. Participants appeared to gain a realization that being true to oneself was perhaps the most powerful and authentic way for them to approach living with their diagnosis. From the initial unexpected diagnosis experienced as “out of the blue like lightning,” the participants and those around them looked for a cure or remission seeking second, third, or fourth opinions as evidenced by “no stone left unturned.” The participants expressed “knowing what I don’t want to know, and not knowing what I want to know” when they talked about the poor prognostic outcomes, their hope for remission, and the loss of living a normal life. Relationships with others quickly became differentiated as close or distant, depending on the ability of others to process the realities of the participant’s experience and their ability to respond. Cues were given and received as “watching you watching me—we are both afraid.” Important conversations occurred in response to the ability of each person to accept the implications of both the diagnosis and the treatment. Participants were observed as “talking yet not talking about death” when they sometimes started talking about death, but then avoided the topic. Participants expressed the realization that “now I have to take care of me,” which evolved in the midst of the experience. In a concept analysis of the variable authenticity, Starr (2008) determined that the defining attributes included the process of self-discovery, realizing and acting on personal potential, and accepting the responsibility for life choices. Although the diagnosis of ovarian cancer was not a voluntary life choice, these participants demonstrated an assumption of responsibility for choices thrust on them by the diagnosis. In doing this, they seemed to reach a place of self-discovery, realizing and acting on their personal potential as reflected within the six subcategories. Therefore, the self who emerged because of living with and responding to the diagnosis of and treatment for ovarian cancer contributed to the emergence of an authentic self.

In the midst of personal processing of existential issues, the social network was an integral part of the picture, contributing both support and additional or intensified distress. Data analysis revealed that individuals within the participant’s social network (spouse or significant other, family, and friends) also were affected by the diagnosis and treatment. This created a dynamic duality where the participant had to process her experience at both a personal and relationship level, whereas those around her were similarly processing their (as well as her) experience.

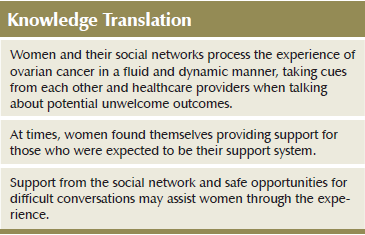

Implications for Nursing

Social support for women diagnosed with and treated for ovarian cancer has been hypothesized to lead to improved health outcomes. Lutgendorf et al. (2005) examined correlations of biomarkers and social support, finding that women with benign disease, greater social support, and less distress had higher levels of natural killer cell activity. Lobchuk and Bokhari (2008) found lower levels of anxiety and depression in women with ovarian cancer who reported greater perceived support. Findings from the current study suggest that the support network may, at times, add to the distress women experience. In this study, some women provided support for their own social network, that is, they ended up supporting the people who were their support system. Although some participants related this to their role as caregiver in the family, others related it to their personal action plans.

Study findings may inform nursing practice by providing insight into the perceptions of women living with ovarian cancer. For example, one participant observed that nurses are “there to make sure you are okay” and several others credited nurses for providing information and support. Some practical nursing actions might include (a) normalizing difficult conversations through the routine use of instruments such as the Distress Thermometer (NCCN, 2014) or documents such as The Five Wishes (http://agingwithdignity.org), (b) ensuring that the patient is not alone when receiving an unfavorable diagnosis or test results, (c) promoting self-care activities and positive coping skills, (d) supporting efforts to identify reliable second opinions and alternative treatments, as well as clinical trials, (e) providing support and resources for the social network, and (f) increasing nurse self-awareness and listening skills so that unintended nonverbal communication is minimized.

Finding a new normal with truth, but also hope, is a major task for women living with ovarian cancer who do not always know what they want or need, but also have concern for how their experience is affecting others around them. Because nurses are identified as trusted healthcare providers, they have a unique opportunity to support women who have been diagnosed with and treated for ovarian cancer, particularly when they are armed with information, such as has emerged from the reported study findings.

Research Implications

Future studies that examine the experience for women living with ovarian cancer hold potential to further contribute to the science of nursing care and practice as it relates to this patient population. Several research suggestions resulting from the current study include exploration of the nurse’s role in communicating life-threatening diagnoses, supporting patient’s self-management and self-advocacy, and contributing opportunities to discuss difficult topics in a safe environment for women and their social network. In addition, future studies should examine the effects of age and development stage, disease stage and treatment or recurrence, ethnicity or culture, and financial or occupational status on distress in women diagnosed with and treated for ovarian cancer.

Conclusions

The current study provides information about the experience of distress from the perspective of women diagnosed with and treated for ovarian cancer. Participants provided both direct and indirect answers to the research question with great depth and personal meaning. Limitations include a small sample size and divergence from Glaserian methodology. Adherence to Glaserian methodology would not have included a preresearch literature review, would not start with a research question and an interview guide, and would have used theoretical sampling, which may have led to interviews with individuals in the social network and healthcare providers. The proposed theory of existential assault emerged using constant comparative analysis and abstraction and conceptualization of substantive data. For these participants, distress was experienced largely within a psychological, psychosocial, and existential context. The imposed ambiguities about their own end-of-life expectations were further complicated by the experience of their social network. In summary, although participants were hesitant or even avoided talk about their own early death, it was a recurring theme across all interviews. An existential assault changed their perception of what was important and was experienced at the personal and relationship levels.

References

American Cancer Society. (2014). Ovarian cancer. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.org/cancer/ovariancancer/index

Arden-Close, E., Gidron, Y., & Moss-Morris, R. (2008). Psychological distress and its correlates in ovarian cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 17, 1061–1072. doi:10.1002/pon.1363

Cain, E.N., Kohorn, E.I., Quinlan, D.M., Schwartz, P.E., Latimer, K., & Rogers, L. (1983). Psychosocial reactions to the diagnosis of gynecologic cancer. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 62, 635–641.

Dawson, T. (1993). Ovarian cancer: The experiences of women after treatment. Journal of Cancer Care, 2, 39–44.

Ferrell, B., Cullinane, C.A., Ervin, K., Melancon, C., Uman, G.C., & Jaurez, G. (2005). Perspectives on the impact of ovarian cancer: Women’s views of quality of life. Oncology Nursing Forum, 32, 1143–1149.

Ferrell, B., Smith, S.L., Cullinane, C., & Melancon, C. (2003a). Psychological well being and quality of life in ovarian cancer survivors. Cancer, 98, 1061–1071. doi:10.1002/cncr.11291

Ferrell, B., Smith, S.L., Cullinane, C., & Melancon, C. (2003b). Symptom concerns of women with ovarian cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 2, 528–538. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00148-9

Ferrell, B.R., Smith, S.L., Ervin, K.S., Itano, J., & Melancon, C. (2003). A qualitative analysis of social concerns of women with ovarian cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 12, 647–663. doi:10.1002/pon.681

Fitch, M.I., Deane, K., Howell, D., & Gray, R.E. (2002). Women’s experiences with ovarian cancer: Reflections on being diagnosed. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 12(3), 152–168.

Glaser, B.G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12, 436–445.

Glaser, B.G. (1992). Basics of grounded theory analysis: Emerging versus forcing. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B.G. (2005). The grounded theory perspective III: Theoretical coding. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B.G. (2012). Stop, write: Writing grounded theory. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press.

Glaser, B.G., & Strauss, A.L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company.

Goff, B.A., Mandel, L., Muntz, H.G., & Melancon, C. (2000). Ovarian carcinoma diagnosis results of a national ovarian cancer survey. Cancer, 89, 2068–2075. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20001115)89: 10<2068::AID-CNCR6>3.0.CO;2-Z

Lobchuk, M.M., & Bokhari, S.A. (2008). Linkages among empathic behaviors, physical symptoms, and psychological distress in patients with ovarian cancer: A pilot study. Oncology Nursing Forum, 35, 808–814. doi:10.1188/08.ONF.808-814

Lutgendorf, S.K., Sood, A.K., Anderson, B., McGinn, S., Maiseri, H., Dao, M., . . . Lubaraoff, D.M. (2005). Social support, psychological distress, and natural killer cell activity in ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23, 7105–7113. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.10.015

Matulonis, U.A., Kornblith, A., Lee, H., Bryan, J., Gibson, C., Wells, C., . . . Penson, R. (2008). Long-term adjustment of early-stage ovarian cancer survivors. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, 18, 1183–1193. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01167.x

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2014). NCCN Guidelines: Distress Management [v2.2014]. Retrieved from http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cml.pdf

Norton, T.R., Manne, S.L., Rubin, S., Carlson, J., Hernandez, E., Edelson, M.I., . . . Bergman, C. (2004). Prevalence and predictors of psychological distress among women with ovarian cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22, 919–926. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.07.028

Norton, T.R., Manne, S.L., Rubin, S., Hernandez, E., Carlson, J., Bergman, C., & Rosenblum, N. (2005). Ovarian cancer patients’ psychological distress: The role of physical impairment, perceived unsupportive family and friend behaviors, perceived control, and self-esteem. Health Psychology, 24, 143–152.

Ponto, J.A., Ellington, L., Mellon, S., & Beck, S.L. (2010). Predictors of adjustment and growth in women with recurrent ovarian cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 37, 357–364. doi:10.1188/10.ONF.357-364

Portenoy, R.K., Kornblith, A.B., Wong, G., Vlamis, V., Lepore, J.M., Loseth, D.B., . . . Hoskins, W.J. (1994). Pain in ovarian cancer patients. Cancer, 74, 907–915. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19940801) 74:3<907::AID-CNCR2820740318>3.0.CO;2-#

Portenoy, R.K., Thaler, H.T., Kornblith, A.B., Lepore, J.M., Friedlander- Klar, H., Kiyasu, E., . . . Norton, L. (1994). The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale: An instrument for the evaluation of symptom prevalence, characteristics and distress. European Journal of Cancer, 30A, 1326–1336.

Power, J., Brown, L., & Ritvo, P. (2008). A qualitative study examining psychosocial distress, coping, and social support across the stages and phases of epithelial ovarian cancer. Health Care for Women International, 29, 366–383. doi:10.1080/07399330701876521

Reb, A.M. (2007). Transforming the death sentence: Elements of hope in women with ovarian cancer [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 34, E70–E81. doi:10.1188/07.ONF.E70-E81

Schulman-Green, D., Bradley, E.H., Nicholson, N.R., George, E., Indeck, A., & McCorkle, R. (2012). One step at a time: Self-management and transitions among women with ovarian cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39, 354–360. doi:10.1188/12.ONF.354-360

Starr, S.S. (2008). Authenticity: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 43(2), 55–62.

About the Author(s)

Judith DellaRipa, PhD, RN, FNP-BC, is an advanced practice nurse at Bon Secours Richmond Health System in Virginia; Annemarie Conlon, PhD, MBA, MSW, LCSW, is an assistant professor in the School of Social Work at Virginia Commonwealth University in Richmond; Debra E. Lyon, PhD, RN, FAAN, is the Kirbo Endowed Chair in the Department of Adult and Elderly Nursing in the College of Nursing at the University of Florida in Gainesville; Suzanne A. Ameringer, PhD, RN, is an associate professor in the Department of Family and Community Health Nursing in the School of Nursing at Virginia Commonwealth University; Debra Lynch Kelly, PhD, RN, OCN®, is an assistant professor in the Department of Adult and Elderly Nursing in the College of Nursing at the University of Florida; and Victoria Menzies, PhD, RN, PMHCNS-BC, is an associate professor in the School of Nursing at Virginia Commonwealth University. No financial relationships to disclose. DellaRipa can be reached at dellaripa1@comcast.net, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted October 2014. Accepted for publication January 9, 2015.)