A Motivational, Gender-Sensitive Smoking Cessation Resource for Family Members of Patients With Lung Cancer

Purpose/Objectives: To gather feedback on an innovative gender-sensitive booklet that draws on emotional connections and relationship factors to motivate smoking cessation.

Research Approach: Qualitative, descriptive.

Setting: Six provinces in Canada.

Participants: 30 family members of patients with lung cancer who were currently smoking or had recently quit.

Methodologic Approach: Parallel booklets for women and men were developed using language and images to emphasize family relationships and gender considerations to motivate smoking cessation. Participants were provided with the women’s and men’s versions of the resource, and they were asked to review the gender-specific version of the booklet that was relevant to them. Semistructured telephone interviews were conducted, and transcriptions were analyzed for themes.

Findings: Three themes were evident in the data, including “new perspectives: appreciating the effects of smoking on relationships,” “reconsidering smoking cessation: relatioal motivation,” and “gendered connections: recognizing themselves in the booklet.” Although participants voiced other important reasons for smoking cessation, family relationships appeared to bolster motivation for stopping smoking. The majority of participants recommended that the dual-format booklet be available in healthcare settings.

Conclusions: A gender-sensitive approach that focuses on relationship factors represents an acceptable way to engage relatives of patients with lung cancer in discussions to support smoking cessation.

Interpretation: Approaches to supporting smoking cessation among relatives of patients diagnosed with lung cancer should draw on positive relationship bonds and caring connections to motivate cessation.

Jump to a section

Lung cancer causes more deaths among women and men of all ethnicities than any other type of cancer in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011) and worldwide, and most of these deaths are caused by smoking (World Health Organization, 2015). Tobacco use is the most important and modifiable risk factor influencing the prevalence and occurrence of lung cancer (World Health Organization, 2015). The majority of patients diagnosed with lung cancer have a history of smoking cigarettes (Park et al., 2012). Tobacco use tends to cluster in families (McBride & Ostroff, 2003). The intergenerational effects of smoking are significant, and children of adults who smoke are as many as four times more likely to smoke (den Exter Blokland, Engels, Hale, Meeus, & Willemsen, 2004; Vuolo & Staff, 2013). For this reason, lung cancer and tobacco use may be viewed as a family health issue.

Patients with lung cancer often quit around the time of their diagnoses; however, these patients who have recently quit are highly vulnerable to relapsing (Park et al., 2012) and less likely to quit or stay quit when family members continue to smoke (Schnoll et al., 2002). The family members of patients diagnosed with lung cancer may state that they feel more motivated to quit smoking (Butler, Rayens, Zhang, & Hahn, 2011); however, previous research indicates that a lung cancer diagnosis in the family does not consistently motivate family members who smoke to quit (Bottorff, Robinson, Sullivan, & Smith, 2009; Robinson, Bottorff, Smith, & Sullivan, 2010; Robinson, Bottorff, & Torchalla, 2011; Sarna et al., 2006). In a study with patients undergoing thoracic surgery and their partners, most patients set a quit date to stop smoking before surgery, but only half of the family members set quit dates (McDonnell et al., 2014).

Family members rationalize their continued smoking by distancing and disputing the link between smoking and cancer, or by asserting the argument that smoking and quitting is a matter of individual choice (Robinson et al., 2010). This is particularly problematic given the known risks associated with continued smoking in the family (Bottorff et al., 2009; Zang & Wynder, 1996). Smoking cessation of patients’ family members not only offers health benefits for the individuals who quit, but also may result in recovery benefits for patients with lung cancer by reducing exposure to secondhand smoke, reducing risk of relapse, decreasing worry about relatives who smoke (Bottorff et al., 2009; McDonnell et al., 2014), and reducing tension among family members caused by continued smoking (Bottorff et al., 2009).

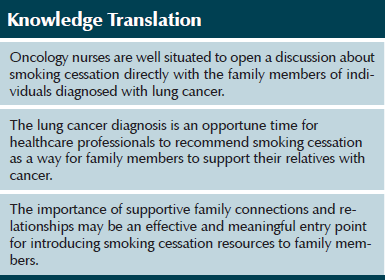

A lung cancer diagnosis represents an opportunity for health professionals to address smoking cessation among patients with lung cancer and their family members who smoke (McBride & Ostroff, 2003; Robinson et al., 2010). Smoking is considered an individual behavior; therefore, most smoking cessation interventions target the individual smoker and do not take family dynamics into consideration. In addition to family relationships, important links between cigarette smoking and gender roles and identities have been described in a small field of research. For example, men often take up smoking because it is viewed as manly and exemplary of traditional masculine strength and autonomy, whereas women often initiate or continue smoking to deal with negative feelings, control stress, and enact freedom from feminine stereotypes of the “good girl.” These gender-related influences need to be considered when designing interventions to assist women and men in reducing and quitting smoking. Increasing evidence supports gender-sensitive and gender-specific approaches in the development of smoking cessation resources (Bottorff et al., 2014; Okoli, Torchalla, Oliffe, & Bottorff, 2011; Torchalla, Okoli, Hemsing & Greaves, 2011).

The purposes of this study were (a) to gather feedback on, and evaluate the acceptability of a new, evidence-based and gender-sensitive resource for family members who continue to smoke after a relative is diagnosed with lung cancer and (b) to identify opportunities for healthcare providers to make use of this new resource to promote smoking cessation among relatives of patients with lung cancer.

Methods

This study adhered to a qualitative methodology known as interpretive description, an approach suited to research questions with clinical and practice-based implications (Thorne, Kirkham, & O’Flynn-Magee, 2008). Interpretive description, an inductive and constructivist method, allowed the research to extend beyond a description of smoking patterns in families that include a patient with lung cancer to generate an explanation and interpretation of this phenomenon and to apply those understandings in the context of nursing practice.

Booklet Development

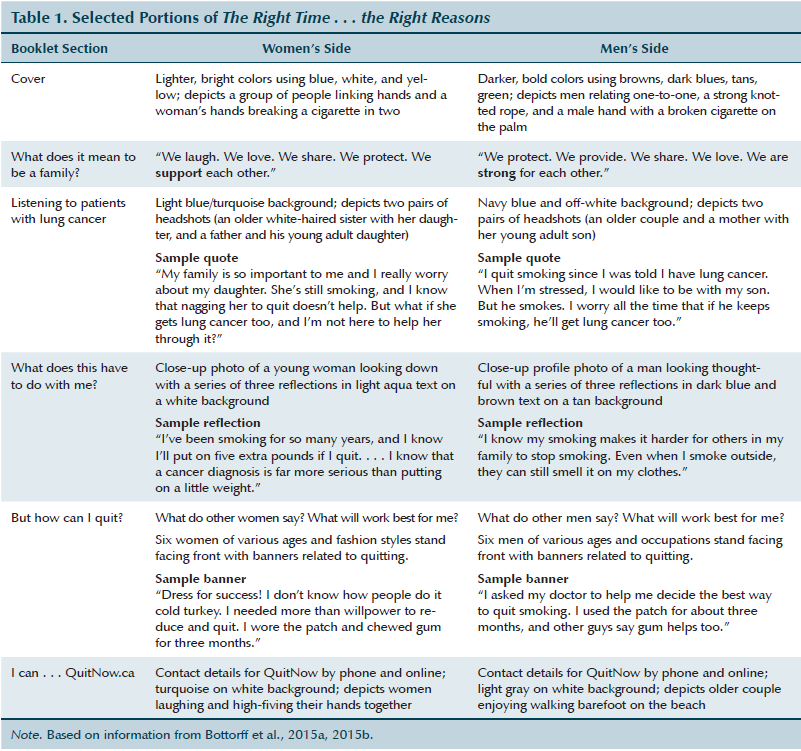

Previous research findings and emerging evidence related to gender influences and smoking cessation (Bottorff et al., 2009, 2014) informed the development of a gender-sensitive booklet to motivate smoking cessation among family members of patients with lung cancer. The gender-tailored resources were combined in a two-sided booklet, one side for women and one side for men, and conveyed the dynamics related to family smoking in the context of lung cancer. The authors chose gender-specific language and images based on extended family relationships as the underlying force to motivate smoking cessation. The guiding principles included using first-person voices of patients with lung cancer and family members, making use of engaging and interactive content that reflected the reality and diversity of people’s everyday family lives, avoiding shame and blame, and incorporating strength-based positive messages that generate emotional connections. The resource was purposely designed to evoke emotions that families experience when they have members with lung cancer, address misconceptions about smoking within the context of families that have a member with a cancer diagnosis, and illustrate how family members can support and strengthen their relationships by eliminating tobacco. During regular team meetings, the booklets were refined based on feedback from expert reviewers (e.g., tobacco control experts, healthcare professionals who work with patients with lung cancer and their families). Select components of the booklet are shown in Table 1.

Recruitment and Data Collection

Eligible participants were individuals aged 19 years or older who were related to a person with a lung cancer diagnosis, were current smokers or smokers who recently quit, and were able to read and speak English fluently. The majority of participants (n = 30) were recruited using social media and online classified advertisements in Canada. Ethical approval was granted by the Behavioural Research Ethics Board at the University of British Columbia in Kelowna, Canada.

The participants received a copy of the consent form via mail or email, depending on their preference. After providing informed consent and completing a demographic and smoking history questionnaire, participants received a copy of the gender-sensitive booklet in the mail. About one week later, participants completed an audio-recorded telephone interview. The interviews were semistructured and lasted about 45 minutes. Open-ended interview questions focused on feedback about the booklet, and participants were invited to share their personal experiences with lung cancer, family relationships, and smoking history and patterns. A series of rating questions using a five-point Likert-type scale were also included to obtain quantitative feedback about the booklet. Upon completion of the study, conducted from July 2013 to April 2014, participants received a $50 honorarium to thank them for their time.

Data Analysis

An interpretive thematic analysis was conducted on transcribed interviews (Thorne et al., 2008). The research team developed a coding framework based on the readings of multiple interview transcripts and meetings to discuss the codes. Employing iterative debate and constant comparative strategies, the team reached consensus on the patterns they identified and constructed within and across the data. Qualitative data were coded using NVivo 10. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize sample characteristics and ratings on the booklet.

Findings

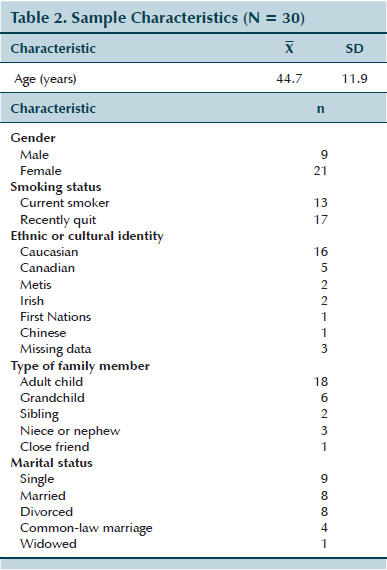

The sample consisted of 21 women and 9 men (see Table 2). Participating family members included adult children, adult grandchildren, nieces or nephews, siblings, and close family friends of a person with lung cancer. With the exception of one, the participants’ family members with lung cancer had died prior to the study.

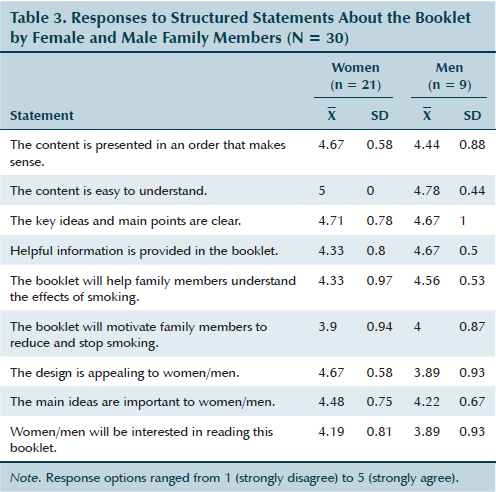

Overall, the participants endorsed the booklet and rated it positively in terms of content, design, and influence as a cessation aid (see Table 3). Three major themes were identified from participants’ reactions to the booklet, including “new perspectives: appreciating the effects of smoking on relationships,” “reconsidering smoking cessation: relational motivation,” and “gendered connections: recognizing themselves in the booklet.”

New Perspectives: Appreciating the Effects of Smoking on Relationships

The lung cancer diagnosis and death in the family significantly affected family members; however, many participants said reading the booklet helped them to truly consider, for the first time, the perspective of the patient regarding smoking by close relatives. The booklet allowed family members to step out of their own shoes and consider the influence of smoking on relationships in a new way. For example, a 20-year-old man who quit smoking and whose grandfather had died of lung cancer explained,

I just mostly thought about the pleasure of smoking instead of the adverse effects it would have on my relationships. And how hard it is for other people to quit when I keep smoking. . . . The part that affected me the most was the part with the mother who was concerned about her son after she had gotten cancer. My mom does that a lot—she worries when I smoke.

Several participants reflected on how their family members with cancer likely perceived their smoking in the past. A 48-year-old woman who had recently quit smoking reflected on her mother’s experience in relation to one of the true-or-false statements that said, “People with lung cancer worry about their family members who smoke.” She said,

A lot of the time, I think the focus is on the sick person and how they’re doing rather than what they’re thinking, right? So I think, if I’m still smoking, then she would probably be worrying about me too. . . . But you’re not really thinking about how she’s worrying about everybody else, so I think [that question is] really good too.

Participants discussed how the booklet led them to reflect on how they would think and feel if they were diagnosed with lung cancer. The vulnerability experienced by family members was particularly salient among those who had young children. For example, a 48-year-old mother described her concern about exposing her children to the same experience she went through learning about her father’s lung cancer.

For me, if I was to have lung cancer, then I think it would be important for me to talk to my kids about it. Whereas my dad didn’t talk to us about it, and I would really hate to be in that position. I always smoke outside, and my kids aren’t around it. I kind of thought that that was taking care of that part, so I wasn’t putting anybody at risk by smoking that way. But I look at it differently now, I guess. I look at it like, it is something I am doing to put myself at risk.

Family members indicated that reading the booklet made them feel more connected to their families, evoked empathy for the point of view of patients, and gave them insight into family conflicts about their continued smoking. A 20-year-old man described how the booklet helped him to understand his parents’ angry attitude toward his past smoking. He said,

Afterwards, I thought about [the booklet], and I understand why so much anger and stuff would happen because of smoking and lung cancer. . . . I understand why I used to argue with my mom and dad so much because of smoking. And now I just understand that they were worried about how bad it is for you.

Reading the booklet invited reflection on self and others that changed how the participants conceptualized the patients’ thoughts and feelings, their own vulnerability, and their relationships with other family members, such as children and spouses. The relationship-oriented nature of the booklet seemed to bring feelings of worry to the forefront, allowing family members to reconsider the tension and defensiveness related to their continued smoking.

Reconsidering Smoking Cessation: Relational Motivation

The participants stated that the booklet changed the way they thought about family interconnections and was a novel approach that motivated smoking cessation. The relationship focus of the booklet emphasized positive family connections as opposed to stigmatizing smoking, and this thematic lens prompted the participants to perceive their own smoking as less of an individual choice or health-risk behavior and more of an interconnected activity that affected their families. For example, a 31-year-old woman who smoked and was the stepdaughter of a person with lung cancer said, “We’re already bombarded with all the dangers on the cigarette packs. This is getting you to think about your family and what’s important.”

A few of the participants who were current smokers indicated that the booklet motivated them to reduce the number of cigarettes they smoked each day. Others stated that the booklet motivated them to reflect on their smoking or bolstered their prior decision to quit. A 23-year-old woman who was a current smoker described how the relationship focus of the booklet motivated her. She said,

I found it did help me to want to reduce. It prompted me to think more about my family and how it affects them. It kind of started to make me associate it in a little more of a gross way rather than like, shameful, which is helpful because I find the shame . . . it really makes me feel guilty, so I’m less inclined to quit. Whereas if I look at it in a way of how much better everything and everyone around me would be if I did quit, it’s kind of more of a motivating factor.

A 43-year-old man who was a current smoker also stated that the booklet motivated him to reduce and prompted him to think about his smoking “more and more.” He attributed the booklet’s positive influence to its overall effect, saying it provided him with “all the negative factors associated with [smoking] and how much it’s costing me and the potential cost to my family.”

A 33-year-old man who was a current smoker said that the booklet inspired him to feel a sense of responsibility to his family, and prompted a “yearning to be close to them in terms of emotional and spending time with one another.” A 45-year-old woman who had lost a parent to lung cancer and continued to smoke talked about how the booklet resonated with her. She referred to a narrative in the booklet about a woman diagnosed with lung cancer who goes out for dinner with her husband and he leaves to go outside and smoke. She found this meaningful because she said she could relate to how one individual’s smoking results in “people sitting alone and missed opportunities to make memories . . . so much missed time.”

Instead of focusing on smoking as a negative habit associated with guilt, the booklet seemed to gently encourage the participants to reflect on themselves as part of a positive, larger whole—the family—and reconsider smoking cessation in light of the benefits of quitting within that larger context.

Most participants suggested that the best time to discuss smoking cessation with relatives who smoke would be at the time a family member is diagnosed with lung cancer. Independent of smoking status, participants conveyed a sense of urgency for the distribution of the booklet. A 21-year-old woman who recently quit smoking described why the booklet would be more helpful earlier in the cancer experience trajectory.

I think that the most effective [time] would be as soon as they find out, like as soon as they’re given the diagnosis, and they know that it’s cancer. That’s when they should be given [the booklet] because after that, once treatment starts, it’s too stressful. Whereas if they find out right away and get this, then it’s like, “Wow, I need to stop.”

A 48-year-old woman who recently quit smoking offered the same opinion and said, “I would say the earlier on, the better. The sooner, the better because, I don’t know, it’s hard because at the beginning, you’re looking for a lot of information about what’s going on.”

The participants agreed the booklet should be distributed in healthcare settings. Some emphasized the importance of receiving the booklet directly from a healthcare provider, and others advised the booklet be displayed and available in waiting rooms or with other brochures to avoid being “too pushy.”

Gendered Connections: Recognizing Themselves in the Booklet

The majority of participants thought it was a good idea to have gender-specific versions of the booklet because of differences in the ways women and men think and respond to issues related to smoking and lung cancer. For example, a 50-year-old woman stated, “Of course it’s the same issue, but as we know, men and women look at things differently. . . . Women look at it emotionally, and men look at it strength-wise.” A 20-year-old man said, “I think it’s useful because, like, pressures that affect women might not affect men. . . . So it’s good to have different perspectives.” A 62-year-old woman who recently quit smoking spoke about the different ways men and women deal with addiction.

Well, you know, an addiction is an addiction, and men and women have different ways of dealing with addiction. Yeah, I think it’s a better idea to have [the booklet] divided. Men, and I don’t know how they do it, but men have a tendency to say, “That’s it; I quit,” and they throw the cigarettes out the car window or the truck window or whatever, and they’re done with it. Whereas women, we don’t, we’re not able to just chuck things out the window.

Many participants expressed the view that they could relate better to the information presented in the gender-specific version because of their own gender identities. A 30-year-old woman who had quit smoking said, “Obviously I liked the women’s side more, I think because it spoke more to me.” Similarly, a 36-year-old man who was a current smoker said, “I liked the men’s side better. Not to be biased, but, yep, I’m a man, so it’s more, or it more directly helps me, you know.”

Participants often strongly identified with a specific representation of a patient or family member depicted in the booklet. In these instances, the persuasive power of the booklet was magnified. A 56-year-old woman who was a current smoker and had lost her mother to lung cancer remarked how the booklet matched her experience. She said, “I think, because of my mom and because of how close I was to her [pause] and her being my best friend, I related to the woman, right?” A 43-year-old woman who had quit smoking referred to a specific representation of family in the booklet, saying, “That part about the mother and daughter, I think about that all the time. That was probably my biggest reason for quitting, was my child. That’s a huge thing when you’re making a book, to talk about family like that.”

When the representation of gender failed to connect with a participant’s experience, it diminished the message. A 48-year-old woman, who was a single parent and had quit smoking, critiqued the booklet’s language for linking the family provider role with men only. Despite this lack of connection for her, she approved of the gender-specific approach saying, “It’s good because . . . among our group of friends, the men have a way higher success rate of quitting.”

Perhaps the strongest testimony supporting the power of gender-specific messaging came from a 23-year-old woman who was a current smoker. She said, “I did relate to the women’s [side] better, being a woman myself. It was kind of empowering to see all these other women that had quit.”

Although most participants found it was effective to have a gender-specific booklet, a few were puzzled about the reason. These participants focused more on medical facts about lung cancer, expressing the view that lung cancer affects men and women in similar ways, negating the need for separate booklets. In addition, because the booklet was distributed in Canada, a bilingual country where documents are usually printed in English and French, some participants assumed the opposite side of the booklet was a French version and therefore ignored that side.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate a gender-sensitive booklet that emphasizes relationship factors and emotional connections among family members to motivate smoking cessation. This resource provides a novel approach to smoking reduction and cessation and demonstrates how motivational health messaging using an evidence-based narrative grounded in the everyday experience of men and women may be helpful in motivating family members of patients with lung cancer to quit. Emphasizing family ties and mutual support may be effective in softening family members’ reticence to quit and opening up space for smoking cessation as a way to protect and preserve family relationships.

The findings reinforce the need for less reliance on individualistic approaches to smoking cessation that have dominated the field and to consider the important role that relationships play in influencing smoking behaviors. The success of an individual’s efforts to quit smoking is strongly influenced by the smoking behaviors of spouses and other family members (Bottorff et al., 2005).

Although denormalization of smoking and messages that smoking causes cancer has contributed to reduced smoking rates, patients with cancer and their family members who smoke are at risk for feelings of guilt and shame, poor psychological adjustment, and concealment of smoking (Shin et al., 2014). The approach used in the booklet to engage family members did not appear to trigger feelings of shame and guilt or other sensitivities related to smoking and lung cancer. Minimizing those feelings is likely to be important in reducing resistance to talking about smoking and enhancing psychosocial well-being and mutual support for smoking cessation in a family context.

This gender-sensitive booklet is a motivational tool and not a “how to quit” resource; however, information about how other women and men have reduced and quit smoking is included. The booklet, therefore, provides a valuable complement to other cessation tools and approaches. Programs to support smoking cessation among patients with cancer and their family members are likely to be strengthened by a gender-sensitive approach (Bottorff et al., 2014), as well as by considerations of the influence of gender relations on smoking behaviors (Bottorff, Haines-Saah, Oliffe, & Sarbit, 2012). Further research is necessary to develop tailored smoking cessation programs for patients and their families that are gender-sensitive, as well as stigma-reducing, in their approaches to maximize family support for cessation.

The current study is not without limitations. The sample size was relatively small and consisted of more females than males. In addition, because a convenience sample was used, a selection bias was possible. All but one participants’ family members had died, which could have resulted in a recall bias given the time gap between the lung cancer experience and the study. It would be beneficial to collaborate with healthcare providers to evaluate the efficacy of the booklet in a clinical setting.

Implications for Practice and Conclusions

Family members of people diagnosed with lung cancer are among the most committed smokers. In fact, they often actively dispute the link between smoking and lung cancer (Robinson et al., 2010, 2011). People with lung cancer worry about relatives who smoke and often intervene to get family members to quit (Bottorff et al. 2009). However, this often creates tension within the family, putting relationships at risk at the time when enhanced support is most needed (Bottorff et al., 2009). The benefits of intervening with family members who smoke include supporting quit efforts by people with lung cancer, reducing exposure to secondhand smoke, eliminating smoking-related distress for people with lung cancer, enhancing family support and cohesion, and preventing smoking-related cancer among relatives. The question of how nurses can best support families and encourage smoking cessation at this challenging time remains.

The study participants’ responses offer some clues for the implementation of the booklet in practice. The positive reception to the booklet provides evidence that capitalizing on relationships is motivating in terms of altering smoking behavior, which suggests that an approach to smoking cessation conversations with family members could benefit from a relationship focus consistent with the resource. For example, the conversation could be framed from the perspective of relatives’ desire to support their ill family member. A healthcare provider could say, “Family members often want to be helpful at a time like this but don’t know what to do. We recommend that [the person with lung cancer] stop smoking because this helps the treatment be as effective as possible. One thing you can think about to support their efforts and relieve them of worry is to stop smoking as well. Here’s a booklet that explains how you can be supportive about quitting smoking.”

Nurses need to interact directly with family members about smoking cessation and avoid working through the person with lung cancer or inadvertently putting the person with lung cancer in the middle. The booklet is a motivational resource and should be supported with additional resources that help people determine the best way for them to quit.

References

Bottorff, J.L., Haines-Saah, R., Kelly, M.T., Oliffe, J.L., Torchalla, I., Poole, N., . . . Phillips, J.C. (2014). Gender, smoking and tobacco reduction and cessation: A scoping review. International Journal of Equity in Health. Retrieved from http://www.equityhealthj.com/content/13/1/114

Bottorff, J.L., Haines-Saah, R., Oliffe, J.L., & Sarbit, G. (2012). Gender influences in tobacco use and cessation interventions. Nursing Clinics of North America, 47, 55–70. doi:10.1016/j.cnur.2011.10.010

Bottorff, J.L., Kalaw, C., Johnson, J.L., Chambers, N., Stewart, M., Greaves, L., & Kelly, M. (2005). Unraveling smoking ties: How tobacco use is embedded in couple interactions. Research in Nursing and Health, 28, 316–328. doi:10.1002/nur.20085

Bottorff, J.L., Robinson, C.A., Sarbit, G., & Torchalla, I. (2015a). The right time. The right reasons: Men related to people with lung cancer talk about reducing and quitting smoking. Retrieved from http://itag.ubc.ca/wp-content/files/Right-Time-Right-Reasons-Men1.pdf

Bottorff, J.L., Robinson, C.A., Sarbit, G., & Torchalla, I. (2015b). The right time. The right reasons: Women related to people with lung cancer talk about reducing and quitting smoking. Retrieved from http://itag.ubc.ca/wp-content/files/Right-Time-Right-Reasons-Women1.pdf

Bottorff, J.L., Robinson, C.A., Sullivan, K.M., & Smith, M.L. (2009). Continued family smoking after lung cancer diagnosis: The patient’s perspective [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 36, E126–E132. doi:10.1188/09.ONF.E126-E132

Butler, K.M., Rayens, M.K., Zhang, M., & Hahn, E.J. (2011). Motivation to quit smoking among relatives of lung cancer patients. Public Health Nursing, 28, 43–50. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00916.x

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). United States cancer statistics: 2011 top ten cancers. Retrieved from http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/uscs/toptencancers.aspx

den Exter Blokland, E.A., Engels, R.C., Hale, W.W., III, Meeus, W., & Willemsen, M.C. (2004). Lifetime parental smoking history and cessation and early adolescent smoking behavior. Preventive Medicine, 38, 359–368. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.008

McBride, C.M., & Ostroff, J.S. (2003). Teachable moments for promoting smoking cessation: The context of cancer care and survivorship. Cancer Control, 10, 325–333.

McDonnell, K.K., Bullock, L.F., Kozower, B.D., Hollen, P.J., Heath, J., & Rovnyak, V. (2014). A decision aid to improve smoking abstinence for families facing cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41, 649–658. doi:10.1188/14.ONF.649-658

Okoli, C.T., Torchalla, I., Oliffe, J.L., & Bottorff, J.L. (2011). Men’s smoking cessation interventions: A brief review. Journal of Men’s Health, 8, 100–108. doi:10.1016/j.jomh.2011.03.003

Park, E.R., Japuntich, S.J., Rigotti, N.A., Traeger, L., He, Y., Wallace, R.B., . . . Keating, N.L. (2012). A snapshot of smokers after lung and colorectal cancer diagnosis. Cancer, 118, 3153–3164. doi:10.1002/cncr.26545

Robinson, C.A., Bottorff, J.L., Smith, M., & Sullivan, K. (2010). “Just because you’ve got lung cancer, doesn’t mean I will”: Lung cancer, smoking and family dynamics. Journal of Family Nursing, 16, 282–301. doi:10.1177/1074840710370747

Robinson, C.A., Bottorff, J.L., & Torchalla, I. (2011). Exploring family relationships: Directions for smoking cessation. In E.K. Svavarsdóttir & H. Jonsdottir (Eds.), Family nursing in action (pp. 137–159). Reykjavik, Iceland: University of Iceland Press.

Sarna, L., Cooley, M.E., Brown, J.K., Williams, R.D., Chernecky, C., Padilla, G., & Danao, L.L. (2006). Quality of life and health status of dyads of women with lung cancer and family members. Oncology Nursing Forum, 33, 1109–1116. doi:10.1188/06.ONF.1109-1116

Schnoll, R.A., Malstrom, M., James, C., Rothman, R.L., Miller, S.M., Ridge, J.A., . . . Goldberg, M. (2002). Correlates of tobacco use among smokers and recent quitters diagnosed with cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 46, 137–145. doi:10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00157-4

Shin, D.W., Park, J.H., Kim, S.Y., Park, E.W., Yang, H.K., Ahn, E., . . . Seo, H.G. (2014). Guilt, censure, and concealment of active smoking status among cancer patients and family members after diagnosis: A nationwide study. Psycho-Oncology, 23, 585–591. doi:10.1002/pon.3460

Thorne, S., Kirkham, S.R., & O’Flynn-Magee, K. (2008). The analytic challenge in interpretive description. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3, 1–11.

Torchalla, I., Okoli, C.T., Hemsing, N., & Greaves, L. (2011). Gender differences in smoking behaviour and cessation. Journal of Smoking Cessation, 6, 9–16. doi:10.1375/jsc.6.1.9

Vuolo, M., & Staff, J. (2013). Parent and child cigarette use: A longitudinal, multigenerational study. Pediatrics, 132, e568–e577. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-0067

World Health Organization. (2015). Cancer fact sheet no. 297. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs297/en/index.html

Zang, E.A., & Wynder, E.L. (1996). Differences in lung cancer risk between men and women: Examination of the evidence. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 88, 183–192. doi:10.1093/jnci/88.3-4.183

About the Author(s)

Joan L. Bottorff, RN, PhD, FCAHS, FAAN, is a professor in the School of Nursing at the University of British Columbia in Kelowna, Canada, and in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Australian Catholic University in Melbourne, Australia; Carole A. Robinson, RN, PhD, is an associate professor in the School of Nursing at the University of British Columbia; Gayl Sarbit, PhD, is a knowledge broker, Raquel B. Graham, BA, is a research assistant, and Mary T. Kelly, MA, is a research coordinator, all in the Institute for Healthy Living and Chronic Disease Prevention at the University of British Columbia; and Iris Torchalla, PhD, R.Psych, is a scientist in the Centre for Health Evaluation and Outcome Sciences at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. This study was supported in part by the Canadian Institute of Health Research. Bottorff can be reached at joan.bottorff@ubc.ca, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted November 2014. Accepted for publication January 16, 2015.)