Patterns of Response in Parents of Children With Cancer: An Integrative Review

Problem Identification: To identify patterns of response of parents in relation to taking care of their child with cancer.

Literature Search: The search was performed using CINAHL® and Scopus in February 2013.

Data Evaluation: The selection process resulted in 18 articles with a wide range of methodologic approaches. The description of the research methods of each study and the relevance of the results in comparison to the purpose of this review were established as assessment criteria.

Synthesis: The results of the studies were analyzed using Meleis’s Transition Theory, identifying a vast number of patterns of response developed by the parents. These patterns of response were analyzed, compared, and split into four themes.

Conclusions: Using this methodology, a wide range of behaviors, attitudes, and competencies associated with the circumstance of parents caring for a child with cancer could be identified.

Implications for Practice: Knowledge of the patterns of response will enable nurses to lead parents through a healthy transition process in caring for their children with cancer.

Jump to a section

After receiving the diagnosis of a serious illness in a child, parents are faced with the loss of the child’s health and the risk of the child dying. Young, Dixon-Woods, and Heney (2002) state that the cancer diagnosis of a child is the beginning of a process that will trigger a major transition in the family. Family members will have to reorganize themselves, and plans and expectations have to be adapted to the circumstances of having a child with cancer (Silva, 2009). The child’s condition means that an adult takes on the responsibility for monitoring, managing, and providing the more complex care needed. The mother is usually the main caregiver when a child is diagnosed with cancer (Relvas, 2007; Wegner & Pedro, 2010).

According to Young et al. (2002), becoming the parent of a child with cancer implies a transition process, which involves redefining one’s own identity. Parents will undergo experiences that lead to the reconstruction of their identity. Transition Theory provides a framework for understanding this process as a whole (Meleis, 2010; Meleis, Sawyer, Im, Messias, & Schumacher, 2000). Previous studies by the authors of the current article have revealed that parents caring for a child with cancer go through a transition that involves the redefinition of their identities (Cerqueira & Barbieri, 2012; Silva, 2009; Silva & Barbieri-Figueiredo, 2011).

Meleis et al. (2000) state that such a transition can take different paths; therefore, recognizing the signals that mark the direction of a transition is important. Early recognition of whether the parent and patient are undergoing a healthy process or are in a vulnerable state enables preventive action to steer them toward a successful transition. According to this theory, the progress of a transition can be observed and monitored through a set of expected results called patterns of response. This concept refers to a set of behaviors one would expect to see in a healthy transition (Meleis et al., 2000).

A vast body of scientific research has been published about children with cancer and their families, revealing a deep and extensive knowledge of the topic. The current authors felt it was important to review this literature with the goal of identifying the patterns of response of parents who care for a child with cancer. This integrative review was done following the five stages recommended by Whittemore and Knafl (2005): (a) problem identification, (b) literature search, (c) data evaluation, (d) data analysis, and (e) presentation.

The process was guided by the following initial question: “What are the patterns of response of parents undergoing the experience of taking care of a child with cancer with regard to their daily demands?”

Literature Search

The goal of this review was to gather as much information as possible from credible and high-quality sources, and empirical studies and theoretical works were included as outlined in an integrative review (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

The search terms emerged from the authors’ knowledge of the area of study and population involved. These terms were initially identified in Portuguese. Then, the respective descriptors were identified in English using the National Library of Medicine and the Virtual Health Library. Boolean search terms used included (“parental role” OR “paternal role” OR “maternal role” OR “famil* role” OR “parental skill*” OR “paternal skills*” OR “maternal skill*” OR “famil* skill*” OR “parental competence*” OR “paternal competence*” OR “maternal competence*” OR “parental care” OR “paternal care” OR “maternal care” OR “parental caring” OR “paternal caring” OR “maternal caring”) AND (child* OR minor* OR infant* OR adolescen* OR pediatric*) AND (cancer OR neoplasm* OR tumor* OR oncolog*) AND (nurse* OR nursing).

The review question guided the following inclusion criteria: (a) the article deals with the experience of taking care of a child with cancer; (b) the issue is discussed from the perspective of the child’s parents, family, or legal guardian; and (c) the research depicts the items of interest are the experiences linked to the active treatment phase. As such, the following exclusion criteria were defined: (a) experiences linked to the palliative or terminal phase of the illness, (b) experiences during the survivor phase, (c) minutes from scientific conferences, (d) editorials, and (e) opinion articles.

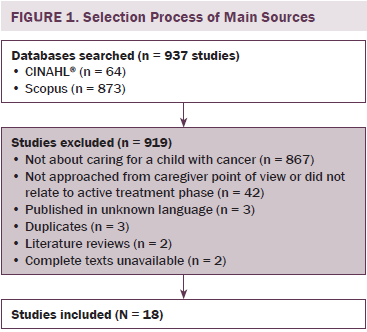

The search was carried out using the CINAHL® and Scopus databases. No time limits were established in the search. The search was carried out in February 2013 and included all the results in the databases up to that date. Using the terms selected for the search, a total of 937 sources were found (see Figure 1). All articles written in Portuguese, Spanish, French, or English were considered.

Data Evaluation

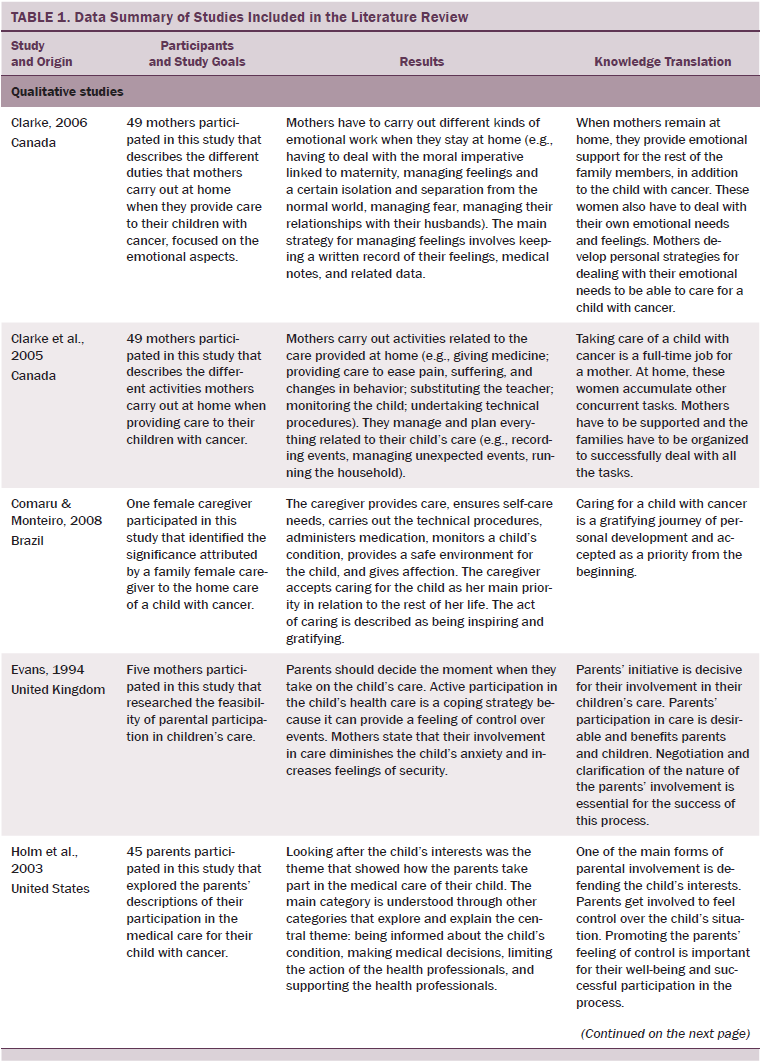

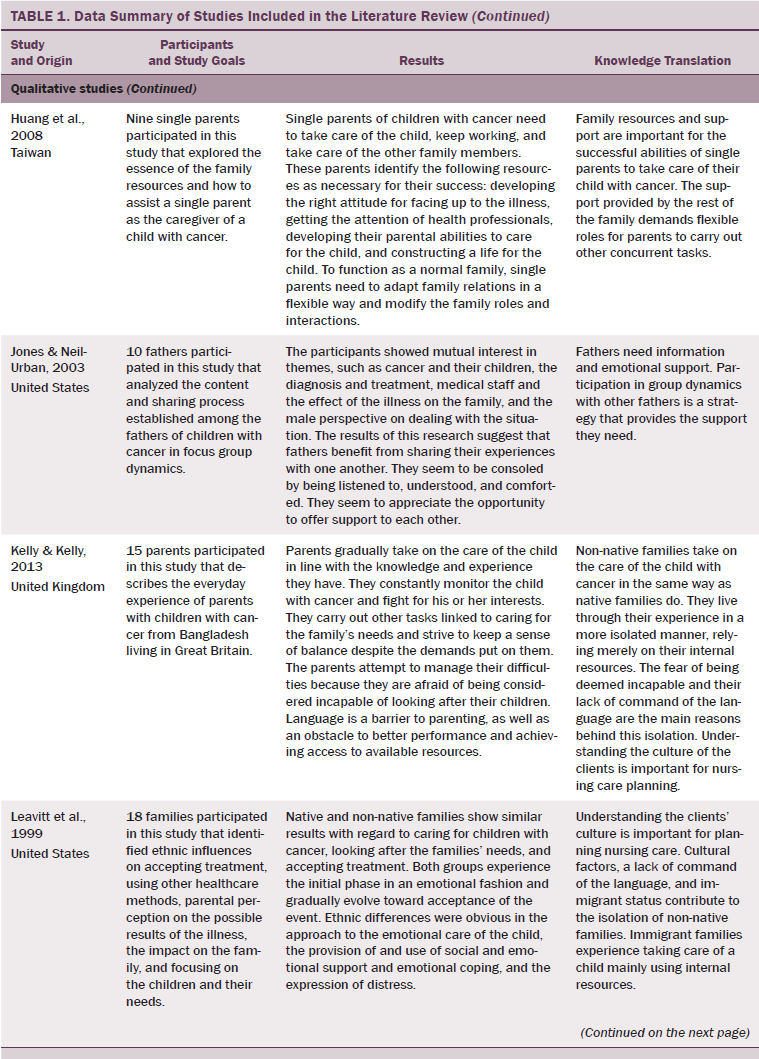

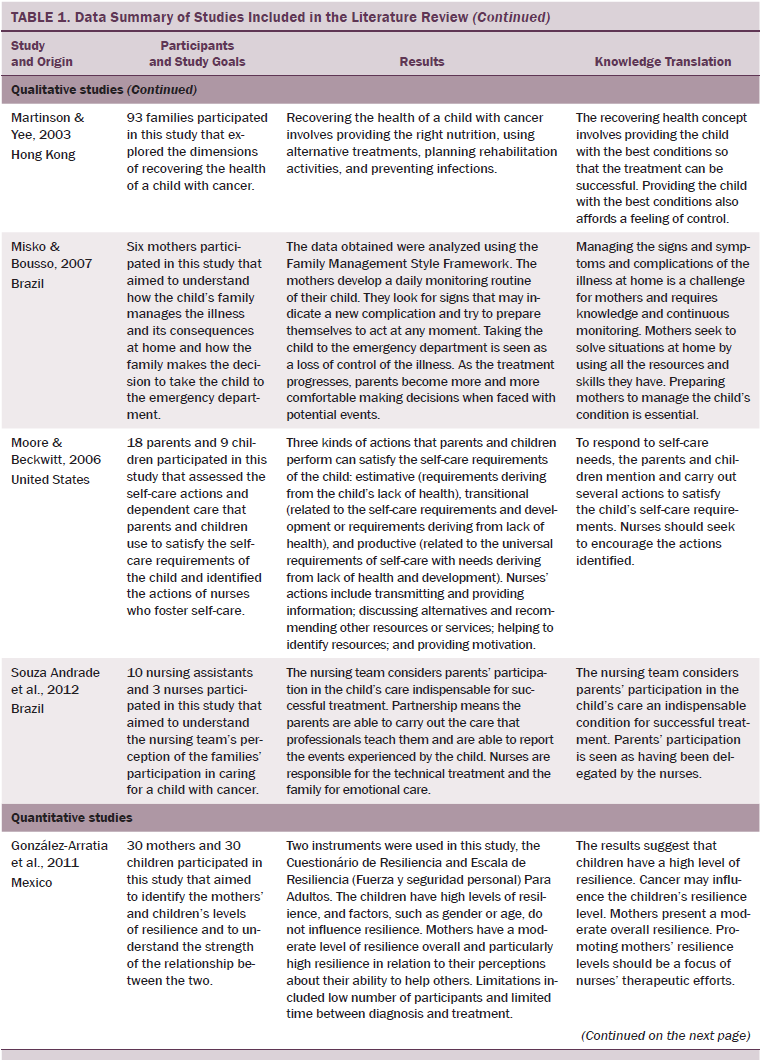

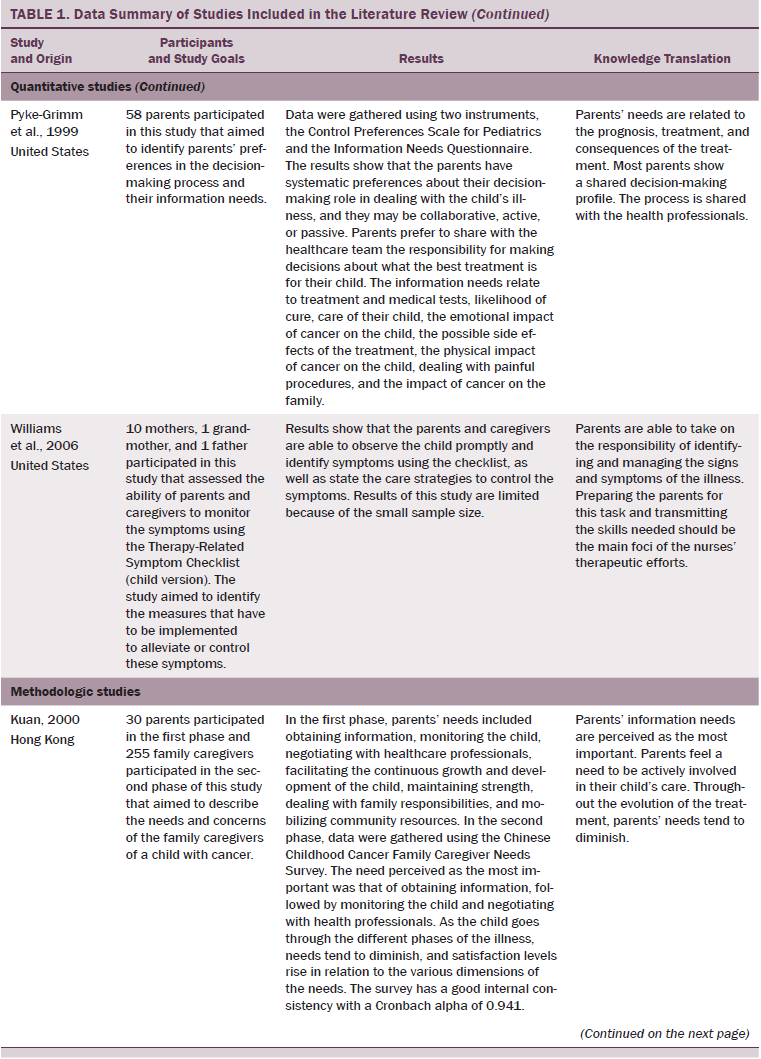

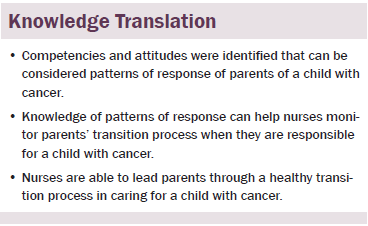

The application of inclusion and exclusion criteria resulted in 18 primary sources in this integrative review. The diversity of sources made it impossible to build an instrument that would allow for the systematic assessment of an array of predefined items. To overcome this issue, the three researchers decided to establish, as assessment criteria, the description of the research methods of each study and the relevance of the results, in accordance with the purpose of this review. Both criteria were evaluated with a two-point scale (1 = low, 2 = high) (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). The reviewers individually assessed each source and decided, by consensus, to include the 18 sources presented in Table 1.

Data Analysis

Taking into account the goals of this integrative review and the diversity of the material gathered, the next step was to organize, codify, and categorize primary sources in accordance with the intended analysis. The strategy was to organize the sources using their methodologic nature as the criterion, which resulted in three subgroups: qualitative, methodologic, and quantitative studies. This strategy facilitated the analysis of the sources and the extraction of data.

To ensure methodologic rigor in data extraction, a set of variables were defined (i.e., methodologic nature of the sources, context of care, subjects involved, main results, knowledge translation, and patterns of response) to guide the selection of content to be drawn from each source. The theoretical and operational definition of each of the variables were followed to facilitate extraction and agreement among the reviewers (Brown, Upchurch, & Acton, 2003).

Data were extracted from each source and reduced to a single-page matrix, highlighting the data under analysis (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). Then, the sources and variables under analysis were placed together into one table according to their methodologic nature, aggregating data for ease of analysis. This allowed for the quick and easy viewing of the sources, the variables under analysis, the methodology used, the results, and conclusions with nursing implications.

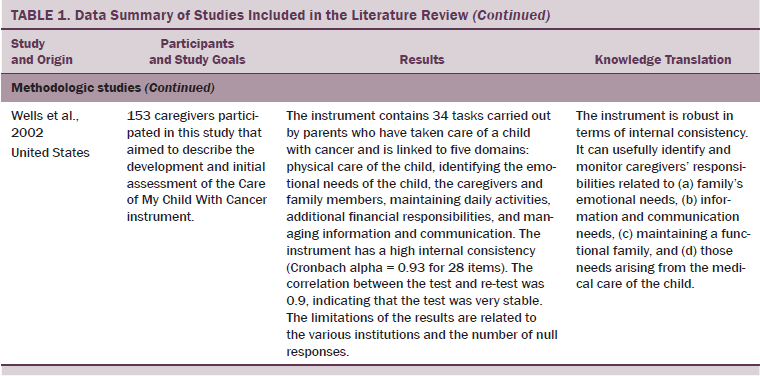

The results, extracted from each source, were reviewed and analyzed. This procedure was undertaken using the Transition Theory as the framework for identifying patterns of response of the parents of a child with cancer (Meleis, 2010; Meleis et al., 2000). An extensive list of behaviors, competencies, and attitudes was identified, which can be considered patterns of response. These were then compared to seek out relationships among them. Four thematic groups emerged through this process: (a) caring for one’s child with cancer, (b) becoming a partner in caring for one’s child, (c) caring for the family, and (d) living with one’s child with cancer (see Figure 2).

Findings

Caring for One’s Child With Cancer

The theme of caring for one’s child with cancer was underpinned by data from 14 primary sources and reflected the highest number of responses by parents. In the context of the normal growth and development of a child, parents look after the different needs of the child. Previous knowledge of the child can be used to their advantage upon diagnosis because it allows the child’s needs, as well as the resources required to satisfy them, to be identified. The new circumstances after a cancer diagnosis may make it necessary to learn and develop new techniques and skills to carry out self-care activities (Comaru & Monteiro, 2008; Moore & Beckwitt, 2006). The illness and its treatment will become part of the child’s life for an indefinite period of time. Parents develop behaviors to help with the child’s acceptance of the new condition; seek emotional balance, socialization, and integration at school; and develop personal resources (Clarke, Fletcher, & Schneider, 2005; Comaru & Monteiro, 2008; Huang, Mu, & Chiou, 2008; Kelly & Kelly, 2013; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999; Souza Andrade et al., 2012; Wells et al., 2002).

In the context of symptom management, care takes on great importance because changes in the child’s condition may put his or her life at risk. Several behaviors developed by the parents to manage symptoms were identified in the literature, such as identifying changes in the physical condition of the child, making decisions related to care, implementing a broad array of care techniques, monitoring signs resulting from the illness or treatment, accompanying the child during medical procedures, keeping a record of events, and interacting with the healthcare team (Clarke, 2006; Clarke et al., 2005; Comaru & Monteiro, 2008; Holm, Patterson, & Gurney, 2003; Huang et al., 2008; Kelly & Kelly, 2013; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999; Misko & Bousso, 2007; Souza Andrade et al., 2012; Wells et al., 2002).

The child’s condition and treatment must be managed during hospital visits and at home. Parents ensure that the child receives continuous care, allowing them to remain at home as long as possible and receive all necessary attention (Leavitt et al., 1999). To provide the child with access to the necessary resources, parents seek out and use available community resources (Huang et al., 2008; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999; Moore & Beckwitt, 2006; Wells et al., 2002).

Many of the cytotoxic drugs used in the treatment of cancer have toxic effects on hematopoietic progenitor cells, which may result in immunosuppression and blood clotting disorders (Biagi, Bollard, Rousseau, & Brenner, 2003). These are causes of concern and receive close attention from the parent. Parents seek to protect the child from contracting infections. They reduce the child’s exposure to crowded places, keep the home environment clean, control the child’s visitors, and protect the child from infection (Comaru & Monteiro, 2008; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999; Martinson & Yee, 2003).

During cancer treatment, a child may experience symptoms like nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, mucositis, pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and frequent mood changes (Hockenberry et al., 2010). These conditions can lead to changes in the child’s appetite and, as a consequence, changes in nutritional intake, which may result in weight loss and nutritional deficits (Montgomery et al., 2013). A decrease in the energy intake may contribute to an energy deficit with increased metabolic rate and altered physical activity (Brinksma et al., 2012).

Planning a child’s diet and encouraging him or her to eat the food he or she needs is a responsibility of the parents. Providing a diet in accordance with a child’s energy needs becomes an extremely important issue for parents because they understand that restoring and maintaining a child’s physical health is essential. Involving the parents in a child’s care makes them feel useful and more confident in their abilities (Comaru & Monteiro, 2008; Huang et al., 2008; Kelly & Kelly, 2013; Kuan, 2000; Martinson & Yee, 2003).

The restoration and maintenance of the child’s physical condition is important to parents because they understand that the continuity of treatment and well-being of the child is essential. They feel a need to do more for the child’s health, and some do so by using complementary therapies in association with conventional medical treatment. These measures are often closely linked to diet and include supplementary ingredients (e.g., vitamins), certain medicinal foods, and plants (Comaru & Monteiro, 2008; Huang et al., 2008; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999; Martinson & Yee, 2003; Williams, Schmideskamp, Ridder, & Williams, 2006).

Parents make it their mission to defend a child’s rights and interests. This results from the emotional relationship between them and from the clear perception that the child is vulnerable, exposed to risks, and unable to defend him or herself alone. Parents defend a child’s interests and protect him or her from any harm that might result from the action of the healthcare professionals by seeking the best care for the child and selecting what they believe to be the best resources available (Holm et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2008; Kelly & Kelly, 2013; Kuan, 2000; Souza Andrade et al., 2012).

Despite the parents’ involvement in providing the complex care arising from the illness and treatment, healthcare professionals become a constant presence in the child’s life. The relationships established between these professionals and the child should make the process easier and promote positive feelings for the child. The parents try to make the child feels comfortable in the presence of professionals by establishing a relationship of trust with them (Martinson & Yee, 2003).

Becoming a Partner in Caring for One’s Child

The theme of becoming a partner in caring for one’s child was supported by data from 10 primary sources. The parents who take responsibility for caring for their children accompany them at the hospital and at home. This results in close and constant contact with the healthcare professionals and with a child’s treatment and needs. At the beginning, the parents may not know much about the illness and its treatment. Progressive involvement in the child’s care, involvement with healthcare professionals, and the need for more knowledge about the illness and its treatment promote the search for information. The knowledge gained helps the parents feel like they are somewhat in control of the situation because they are able to interpret and predict events, giving them firmer ground to make decisions and allowing them to believe they can provide the best possible care (Holm et al., 2003; Jones & Neil-Urban, 2003; Kelly & Kelly, 2013; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999; Misko & Bousso, 2007; Moore & Beckwitt, 2006; Souza Andrade et al., 2012; Wells et al., 2002).

As the illness and its treatment advance, the parents become more and more aware of their children’s needs and prepare to take over care. In the hospital, parents and healthcare professionals may share responsibilities for decisions about treatment and care. When the child returns home, parents have to make decisions and provide the care based on their knowledge and experience. They become conscious of their role in the caregiving team and gradually adapt their position and functions in relation to the rest of the team (Evans, 1994; Holm et al., 2003; Jones & Neil-Urban, 2003; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999; Misko & Bousso, 2007; Souza Andrade et al., 2012). Sharing the provision of health care and making sure of continuity of care across the different settings are two behaviors associated with the care partnership between parents and healthcare professionals (Clarke et al., 2005; Misko & Bousso, 2007; Souza Andrade et al., 2012). Trust is essential for a successful relationship between parents and healthcare providers. Behaviors expressed by parents include trusting the care team, recognizing the competence of these professionals, and fostering relationships with the care team (Holm et al., 2003; Kuan, 2000; Pyke-Grimm, Degner, Small, & Mueller, 1999).

Caring for the Family

The theme of caring for the family was based on data from nine primary sources. A diagnosis of cancer in a child disrupts the family’s functional balance. The needs of each of its members have to be looked after, particularly if other children are involved. The social and financial commitments also have to be safeguarded. Parents, in addition to having to take care of a child with cancer, have to maintain a balanced family and care for their other children. Restoring the balance means being able to identify changes that the child’s illness has caused in each of the family members and in the family unit. To promote the family’s equilibrium, parents develop behaviors, such as identifying the needs of the different members, carrying out everyday chores, giving emotional support to those in need, managing the family finances, establishing new routines, redefining roles, and adjusting short- and long-term family plans (Clarke, 2006; Clarke et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2008; Jones & Neil-Urban, 2003; Kelly & Kelly, 2013; Leavitt et al., 1999; Martinson & Yee, 2003; Wells et al., 2002).

When the family has other children, those children are an added source of worry for the parents (Kuan, 2000). The parents try to maintain their role with the other children despite the circumstances giving rise to frequent physical separations (Leavitt et al., 1999).

They seek to identify the needs of their children as they always did, seeing what has changed for the children, monitoring their reactions to the events, and obtaining the resources that the children need (Jones & Neil-Urban, 2003; Kelly & Kelly, 2013; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999; Wells et al., 2002).

In some cases, the extended family and friends are considered resources to help overcome the parents’ difficulties. The physical distance that separates family members and cultural traditions can be obstacles blocking this collaboration and support. Taking care of a child with cancer, maintaining family balance, and taking care of the other children are demanding tasks that are tiring and often difficult to manage. The support received from extended family members may alleviate the parents’ workload and make it easier for the caregiver, spouse, and children to restore equilibrium. Parents are the people who best know the needs of each family member and know the routines and tasks that have to be carried out, and they are able to identify what they need from the extended family and friends (Huang et al., 2008; Kelly & Kelly, 2013; Kuan, 2000).

Living With One’s Child With Cancer

The theme of living with one’s child with cancer emerged from the data produced by 13 primary sources. The diagnosis of a serious childhood illness is an unexpected event that can change one’s plans and aspirations. The future of the child, as well as his or her physical, cognitive, emotional, and social development, is potentially compromised. Parents fear for the child’s life because they recognize the uncertainties of disease course and treatment (Misko & Bousso, 2007). The treatment is lengthy and involves side effects that have to be controlled. Parents and the child learn to live under these new conditions and develop strategies to carry on with their lives. Parents state that immersing themselves in the child’s care can help this process (Evans, 1994; Huang et al., 2008).

As soon as the parents become aware of the child’s diagnosis and the treatment needed, one of them usually takes on the responsibility of remaining by his or her child’s side and providing the care needed. Accepting responsibility to be the child’s caregiver is associated not only with the affective bond between the two, but also to parental accountability (Evans, 1994; Huang et al., 2008; Jones & Neil-Urban, 2003; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999; Souza Andrade et al., 2012). Parents’ knowledge and experience in taking care of the child helps them in this task. However, difficulties arise from a combination of factors related to the child, the caregiver, and the context surrounding the illness. In data analyzed in this integrative review, parents mention difficulties related to the child and the care they need and the variability of everyday tasks (Evans, 1994; Jones & Neil-Urban, 2003).

Knowledge about the disease and its treatment, the experience that is acquired throughout this process, and the success of the treatment are conditions that gradually help restore equilibrium. Analysis of the primary sources highlighted behaviors and attitudes (e.g., identifying changes in their lives, accepting the illness, integrating the unpredictability of the illness into daily life, integrating one’s needs, adopting healthy lifestyles, managing one’s emotions, reformulating one’s values, communicating feelings of belonging) that can be linked to this process (Clarke, 2006; Evans, 1994; González-Arratia, Nieto, & Valdez, 2011; Huang et al., 2008; Jones & Neil-Urban, 2003; Kelly & Kelly, 2013; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999; Misko & Bousso, 2007; Wells et al., 2002).

Confidence in their own performance is essential for parents’ well-being and for them to continue performing their role. According to the literature reviewed, confidence is a feeling that results from a combination of factors, such as experience in caring, the ability to make decisions in unexpected situations, the ability to act in defense of the child, and the ability to readily take on responsibility for caring for their child (Holm et al., 2003; Leavitt et al., 1999; Misko & Bousso, 2007).

Parents report that the experience of taking care of a child with cancer leads to the mobilization of capacities that they did not know they possessed and the development of new skills. These circumstances lead to a positive appraisal of themselves and their abilities (Clarke, 2006; González-Arratia et al., 2011).

Data show that parents need to feel they have control over the events related to their child and need to feel confident about the success of the treatment. These feelings are important to help them face their everyday difficulties and to transmit confidence to the child. The coping strategies linked to this issue involve keeping a positive attitude and implementing spiritual practices and habits that boost confidence (Huang et al., 2008; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999).

Discussion

Childhood cancer is a reality that has long been the focus of research by healthcare professionals. Numerous studies have been published on the subject, and the results of different methodologic and theoretical approaches have been disseminated, highlighting a complex reality. The goal of this integrative review was to identify patterns of response presented by parents who care for a child with cancer. The decision to undertake an integrative review of the literature was because of the vast number of studies available and because this approach provided a method that would allow the authors to bring together different kinds of data selected in line with predefined criteria. Using this methodology, identifying a vast range of behaviors, attitudes, and competencies associated with the circumstance of a parent caring for a child with cancer was possible. Parents’ responses were analyzed in terms of their meaning.

The theme of caring for one’s child with cancer was the category with the highest number of patterns of response identified. This finding results from the fact that a substantial part of the studies are centered on the child with cancer, his or her needs, and the care provided to him or her, which results from the centrality that the child with cancer and the related treatment acquires at diagnosis. The child becomes more vulnerable and dependent on others to satisfy his or her needs. This condition gives rise to the need for an adult to take responsibility for being the child’s caregiver, which includes monitoring, managing, and providing the necessary care (Silva & Barbieri-Figueiredo, 2011).

A child with cancer has normal developmental needs, but the circumstance of growing up within the context of a chronic illness adds a set of specific needs. The data revealed that caring for a child with cancer requires parents to develop technical, relational, and emotional skills (Comaru & Monteiro, 2008; Holm et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2008; Kelly & Kelly, 2013; Kuan, 2000; Leavitt et al., 1999; Souza Andrade et al., 2012; Wells et al., 2002).

The theme of becoming a partner in caring for one’s child identified behaviors related to parents taking on the role of the child’s caregiver. They seek the knowledge that allows them to share decisions about the course and treatment options and to carry out most of the care. The parents’ role in caring for a sick child is a consequence of (a) reduced time of hospitalization, (b) implementation of care models centered on the family, and (c) the child’s needs (Smith, Coleman, & Bradshaw, 2006). Studies carried out about the parents’ involvement in taking care of a child with cancer show that adopting this attitude benefits the child and the parents (Mendes & Martins, 2012). The child feels safer and less anxious when care is administered by his or her parent (Kuan, 2000). Parents feel useful and more secure when they are the ones to care for their ill child (Martinson & Yee, 2003; Mendes & Martins, 2012).

The theme of caring for the family resulted from the circumstances of the family caregiver being a parent. The issue was approached from the perspective of illness’s effect on the family as a unit and how the different members dealt with their different needs and roles. Several parental patterns of response were identified in terms of keeping the family functioning smoothly and performing the parental role with other children. Qualitative studies made a major contribution to this dimension, owing to the detailed and wide-ranging description of the results, which revealed a variety of patterns of response. Studies of this topic showed that women are the main caregiver of the child with cancer and seek to continue performing other roles related to maintaining the family (James et al., 2002; Moreira, 2007; Wegner & Pedro, 2010).

The theme of living with one’s child with cancer results from the condition of becoming the caregiver of a son or daughter with cancer. Parents seek to integrate this circumstance gradually into their daily lives and individual needs. They are exposed to daily challenges that test their skills and competencies. Some of the parents’ responses fit in with the findings of the authors’ previous study (Silva, 2009), particularly related to the fact that having a child with cancer can stretch parents to their limits, leading to the discovery of new capacities and weaknesses. Learning new skills and gaining mastery of the new situation increase self-esteem and lead to a positive self-image. Data also reveal that parents feel a need to have control over the illness and, as such, develop responses that allow them to maintain this feeling. Silva (2009) stated that, in an adverse context marked by unpredictability and the possibility of losing a child, parents develop skills that allow them to manage the situation in their daily lives with a degree of optimism and confidence.

One issue to highlight is the fact that, despite the cultural diversity that the review included, patterns of response of parents of a child with cancer present striking similarities predominantly in the theme of caring for a child with cancer.

The findings suggest that caring for a child with cancer is a process that involves instrumental, cognitive, relational, and emotional responses. Additional research is needed to determine which patterns lend themselves to the development of indicators, allowing the monitoring of the transition experienced by parents of a child with cancer.

Implications for Practice and Conclusion

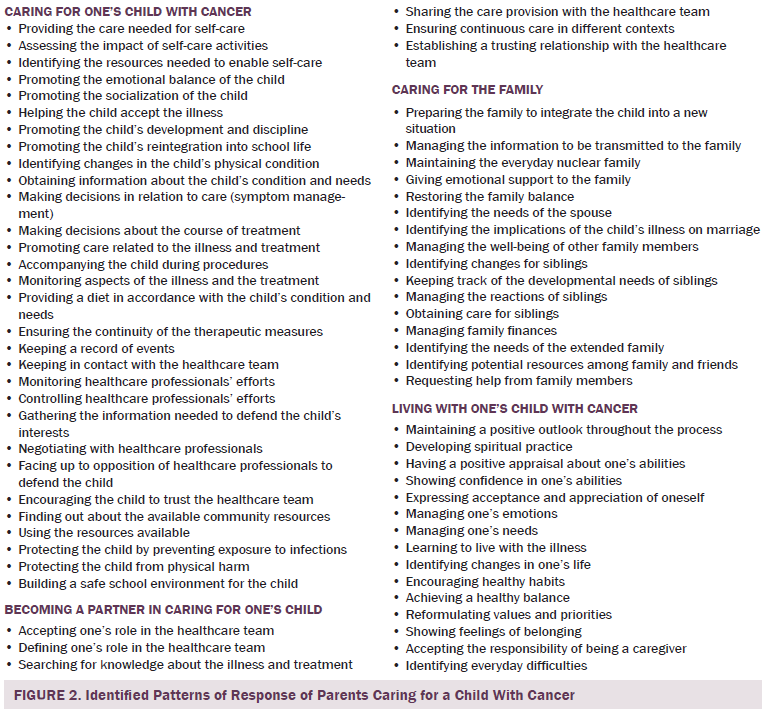

An extensive list of behaviors, competencies, and attitudes was identified in this integrative review, which can be considered patterns of response of parents of a child with cancer. Knowledge of these patterns of response can help nurses monitor parents’ transition process when they are responsible for their child with cancer. Monitoring this process allows nurses to quickly identify vulnerable or at-risk parents and act accordingly to guide them toward a healthy transition. Developing additional knowledge about the patterns of response is still necessary for nursing therapeutics to be developed, implemented, and evaluated (Meleis, 2010).

References

Biagi, E., Bollard, C., Rousseau, R., & Brenner, M. (2003). Gene therapy for pediatric cancer: State of the art and future perspectives. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology, 2003(1), 13–24. doi:10.1155/S1110724303209025

Brinksma, A., Huizinga, G., Sulkers, E., Kamps, W., Roodbol, P., & Tissing, W. (2012). Malnutrition in childhood cancer patients: A review on its prevalence and possible causes. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 83, 249–275. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.12.003

Brown, S.A., Upchurch, S.L., & Acton, G.J. (2003). A framework for developing a coding scheme for meta-analysis. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 25, 205–222. doi:10.1177/0193945902250038

Cerqueira, C., & Barbieri, M.C. (2012). La Teoria de las Transiciones de Meleis en el análisis de la “experiencia de cuidar un niño con câncer” [Abstract]. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/1Tlq1Go

Clarke, J.N. (2006). Mother’s home healthcare: Emotion work when a child has cancer. Cancer Nursing, 29, 58–65.

Clarke, J.N., Fletcher, P.C., & Schneider, M.A. (2005). Mothers’ home health care work when their children have cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 22, 365–373. doi:10.1177/1043454205281834

Comaru, N.R., & Monteiro, A.R. (2008). O cuidado domiciliar à criança em quimioterapia na perspetiva do cuidador familiar. Revista Gaucha de Enfermagem, 29, 423–430.

Evans, M.A. (1994). An investigation into the feasibility of parental participation in the nursing care of their children. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 20, 477–482. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb02384.x

González-Arratia, N.I., Nieto, D., & Valdez, J.L. (2011). Resiliencia en madres e hijos con cáncer. Psicooncología, 8, 113–123. doi:10.5209/rev_PSIC.2011.v8.n1.9

Hockenberry, M.J., Hooke, M.C., Gregurich, M., McCarthy, K., Sambuco, G., & Krull, K. (2010). Symptom clusters in children and adolescents receiving cisplatin, doxorubicin, or ifosfamide [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 37, E16–E27. doi:10.1188/10.ONF.E16-E27

Holm, K.E., Patterson, J.M., & Gurney, J.G. (2003). Parental involvement and family-centered care in the diagnostic and treatment phases of childhood cancer: Results from a qualitative study. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 20, 301–313. doi:10.1177/1043454203254984

Huang, I., Mu, P., & Chiou, T. (2008). Parental experience of family resources in single-parent families having a child with cancer. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17, 2741–2749. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02447.x

James, K., Keegan-Wells, D., Hinds, P.S., Kelly, K.P., Bond, D., Hall, B., . . . Speckart, B. (2002). The care of my child with cancer: Parents’ perceptions of caregiving demands. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 19, 218–228. doi:10.1177/104345420201900606

Jones, J.B., & Neil-Urban, S. (2003). Father to father: Focus groups of fathers of children with cancer. Social Work in Health Care, 37, 41–61. doi:10.1300/J010v37n01_03

Kelly, P., & Kelly, D. (2013). Childhood cancer-parenting work for British Bangladeshi families during treatment: An ethnographic study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50, 933–944. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.11.004

Kuan, H.Y. (2000). Identifying the needs of Chinese family caregivers of children with cancer in Hong Kong (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Hong Kong Polytechnic University, China.

Leavitt, M., Martinson, I.M., Liu, C., Armstrong, V., Hornberger, L., Zhang, J., & Han, X. (1999). Common themes and ethnic differences in family caregiving the first year after diagnosis of childhood cancer: Part II. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 14, 110–122.

Martinson, I.M., & Yee, K.H. (2003). Parental involvement in restoring the health of a child with cancer in Hong Kong. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 20, 233–244. doi:10.1177/1043454203254037

Meleis, A.I. (Ed.). (2010). Transitions theory. New York, NY: Springer.

Meleis, A.I., Sawyer, L., Im, E.O., Messias, D.H., & Schumacher, K. (2000). Experiencing transitions: An emerging middle range theory. Advances in Nursing Science, 23, 12–28.

Mendes, M.G.R.S., & Martins, M.M.F.P.S. (2012). Parceria nos cuidados de enfermagem em pediatria; do discurso à ação dos enfermeiros. Revista de Enfermagem Referência, 6, 113–121. doi:10.12707/RIII1144

Misko, M.D., & Bousso, R.S. (2007). Manejando o câncer e suas intercorrências: A família decidindo pela busca ao atendimento de emergências para o filho. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 15, 48–54.

Montgomery, K., Belongia, M., Mulberry, M.H., Schulta, C., Phillips, S., Simpson, P.M., & Nugent, M.L. (2013). Perceptions of nutrition support in pediatric oncology patients and parents. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 30, 90–98. doi:10.1177/1043454212471726

Moore, J.B., & Beckwitt, A.E. (2006). Self-care operations and nursing interventions for children with cancer and their parents. Nursing Science Quarterly, 19, 147–156. doi:10.1177/0894318406286594

Moreira, P.L. (2007). Tornar-se mãe de criança com câncer: Construindo a parentalidade (Unpublished master’s thesis), Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Pyke-Grimm, K.A., Degner, L., Small, A., & Mueller, B. (1999). Preferences for participation in treatment decision making and information needs of parents of children with cancer: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 16, 13–24. doi:10.1177/104345429901600103

Relvas, A.P. (2007). A mulher na família: Em torno dela. In A.P. Relvas & M. Alarcão (Eds.), Novas formas de famílias (pp. 229–337). Coimbra, Portugal: Quarteto.

Silva, C.C., & Barbieri-Figueiredo, M.C. (2011). A Pessoa que vive a experiência de cuidar de um filho com cancro. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Enfermeiros Pediátras, 11, 25–32.

Silva, C.M.C. (2009). A pessoa que cuida da criança com cancro (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universidade do Porto, Portugal.

Smith, L., Coleman, V., & Bradshaw, M. (2006). Family-centred care. In A. Glasper & J. Richardson (Eds.), A textbook of children’s and young people’s nursing (pp. 77–88). London, England: Churchill Livingstone.

Souza Andrade, N.K., Valença, C.N., Lima, G.A.F., Cavalcante, R.D., Scales, L.K.O., & Germano, R.M. (2012). The perception of nursing staff about the participation of familiy in care for child with cancer. Revista de Enfermagem da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, 6, 1790–1797. doi:10.5205/reuol.2931-23598-1-LE.0608201207

Wegner, W., & Pedro, E.N.R. (2010). Os múlltiplos papéis sociais de mulheres cuidadoras-leigas de crianças hospitalizadas. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem, 31, 335–342. doi:10.1590/S1983-14472010000200019

Wells, D.K., James, K., Stewart, J.L., Moore, I.M., Kelly, K.P., Moore, B., . . . Speckhart, B. (2002). The care of my child with cancer: A new instrument to measure caregiving demand in parents of children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 17, 201–210. doi:10.1053/jpdn.2002.124114

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52, 546–553. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Williams, P.D., Schmideskamp, J., Ridder, E.L., & Williams, A.R. (2006). Symptom monitoring and dependent care during cancer treatment in children: A pilot study. Cancer Nursing, 29, 188–197.

Young, B., Dixon-Woods, M., & Heney, D. (2002). Parenting in a crisis: Conceptualising mothers of children with cancer. Social Science and Medicine, 55, 1835–1847. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00318-5

About the Author(s)

Cerqueira is an associate professor, and Pereira and Barbieri Figueiredo are coordinator professors, all at the Higher School of Nursing of Porto in Portugal. No financial relationships to disclose. Cerqueira, Pereira, and Barbieri Figueiredo contributed to the conceptualization and design and analysis. Cerqueira and Barbieri Figueiredo completed the data collection and contributed to the statistical support and manuscript preparation. Cerqueira can be reached at carlacerqueira@esenf.pt, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted February 2015. Accepted for publication May 12, 2015.