Integrative Review of Facility Interventions to Manage Compassion Fatigue in Oncology Nurses

Problem Identification: Oncology nurses are regularly exposed to high-stress situations that may lead to compassion fatigue, and many institutions have implemented interventions to reduce burnout in nurses, but knowledge on the feasiblity, effectiveness, and nurses’ experience of interventions is lacking.

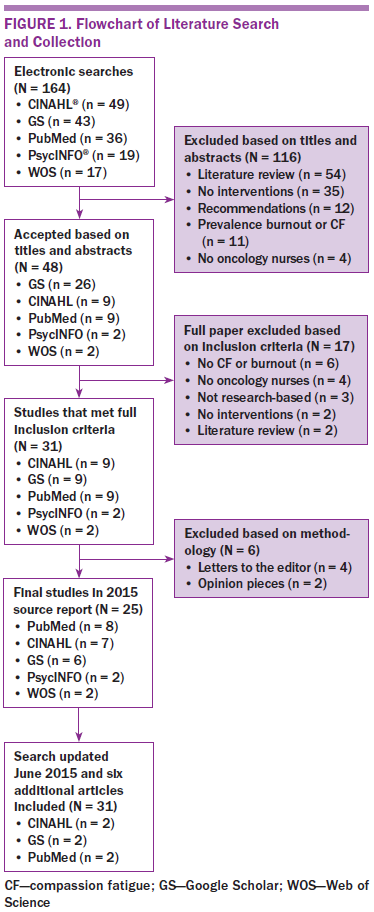

Literature Search: Electronic search of literature published from 1992–2015 was performed to evaluate in-facility interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nurses. Databases used included CINAHL®, PubMed, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and PsycINFO®.

Data Evaluation: The goal was to evaluate the effectiveness, feasibility, and nurses’ experience of interventions to manage compassion fatigue. The study designs, methods, and limitations were independently screened by the authors.

Synthesis: Of 164 studies, 31 met eligibility criteria.

Conclusions: The majority of the studies were conducted in Western countries, which suggests the need for additional research in other settings to determine effective interventions that address compassion fatigue and stress cross-culturally. Quantitative and qualitative studies failed to gain high scores in terms of quality. Limited conclusions can be drawn from small studies that report on outcomes with many confounding variables, such as turnover rate or general health of nurses, from a single institution.

Implications for Research: Lack of empirical precision in evaluating the effectiveness, feasibility, and nurses’ experiences of interventions indicates a need for future, more rigorously designed experimental studies. Because of the global increase in the number of patients being diagnosed and living with cancer, oncology nurses should be able to recognize and manage compassion fatigue.

Jump to a section

Although oncology nursing can be a worthwhile and gratifying career, the highly stressful incidents oncology nurses experience in caring for patients may affect their psychological well-being (Quinal, Harford, & Rutledge, 2009; Zander, Hutton, & King, 2010). Oncology nurses are likely to experience compassion fatigue by repeated exposure to patients who are undergoing numerous and repeated traumas associated with oncology, such as the aggressive side effects of chemotherapy and severe pain experienced in the end stages of cancer (Kash et al., 2000; Potter et al., 2010). This is further compounded by nurses’ lack of technical and theoretical tools to assess patients’ physical and emotional responses, making them feel powerless and potentially leading to compassion fatigue (Lupo et al., 2012). Compassion and empathy often attract nurses to oncology, but empathy for patients with cancer may also result in harmful emotional and physical aftereffects in nurses (McSteen, 2010). The psychological trauma experienced by healthcare workers is currently a subject of interest. The definitions of burnout, secondary stress syndrome, secondary stress in traumatology, secondary victimization, secondary traumatic stress, secondary survivor, compassion fatigue, and vicarious traumatization are used interchangeably, which is sometimes confusing (Coetzee & Klopper, 2010; Najjar, Davis, Beck-Coon, & Doebbeling, 2009).

The symptoms of secondary traumatic stress disorder (STSD) are the same as those of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and can occur as a consequence of helping those with PTSD (Figley, 2003). In his formal definition of compassion fatigue, Figley (2005) likened compassion fatigue to STSD in workers in clinical practice who first witness pain, suffering, and distress. Compassion fatigue is explained as a situation of fatigue stemming from encounters with compassion stress (Figley, 1995), and it surfaces suddenly and without warning, leaving the sufferer feeling confused and helpless (Figley, 2005). The central element in compassion fatigue is a healthcare workers’ capacity for empathy, which enables him or her to enter into a beneficial affiliation with patients (Sabo, 2011). Compassion fatigue has also been said to comprise secondary trauma and burnout (Adams, Figley, & Boscarino, 2007). Compassion fatigue in healthcare professionals may result in occupational hazards related to tiredness and anxiety, including administering incorrect medications, failing to observe patients’ deteriorating condition, failure to ensure patient safety, and reducing quality of care (Boyle, 2011; Kash et al., 2000; Medland, Howard-Ruben, & Whitaker, 2004; Potter et al., 2010).

In the current article, oncology nurses are defined as professional nurses with or without additional oncology qualifications who are currently employed in oncology units, wards, palliative units, or hospices. Occupational grief of oncology nurses is frequently associated with stress, burnout, and attrition. Nurses display significant grief-related symptoms that may, with time, lead to burnout or compassion fatigue (Popkin et al., 2011). Hospice nurses, in particular, are skilled in supporting family members with bereavement, but they frequently ignore their own bereavement. They can become like family to patients, but the cumulative consequence of multiple deaths, coupled with an inability to address each individual death, can be traumatic and devastating, producing chronic stress that renders nurses susceptible to compassion fatigue (Carter, Dyer, & Mikan, 2013; Macpherson, 2008).

Globally, the number of individuals being diagnosed and living with cancer is growing, which further burdens overwhelmed oncology healthcare workers. In addition, the rapid advances in treatment modalities for cancer and the increased survival of patients with cancer expands the need for competent, empathetic, and up-to-date nursing care (van Rooyen, le Roux, & Kotzé, 2008). The literature shows that the impact of compassion fatigue on oncology healthcare professionals results in decreased quality of nursing care, absenteeism, and decreased retention of staff, which is compounded by reduced numbers of nurses trained in oncology (Gillespie, 2013; Girgis, Hansen, & Goldstein, 2009; Medland et al., 2004; Potter et al., 2010).

Only a paucity of evidence-based interventions has been shown to be effective for either the prevention or treatment of compassion fatigue or burnout in healthcare professionals caring for people with cancer (Emanuel, Ferris, von Guten, & von Roenn, 2011). In addition, the formal training of oncology healthcare professionals does not include any solid basis of psychosocial awareness, knowledge, or skills to facilitate emotional coping (Le Blanc, Hox, Schaufeli, Taris, & Peeters, 2007).

Giarelli, Denigris, Fisher, Maley, and Nolan (2016) reiterated the reality of compassion fatigue experienced by oncology nurses and further displayed the necessity of prevention strategies to assist oncology nurses in assessing their own risk of developing and managing compassion fatigue.

The aim of the current study was to identify and assess the evidence regarding the effectiveness, feasibility, and nurses’ experience of in-facility interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nurses. The review questions included the following:

• What is the effectiveness of an in-facility inter-vention to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nurses?

• What is the feasibility of an in-facility intervention to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nurses?

• What are nurses’ experiences of an in-facility intervention to manage compassion fatigue?

Design

The review was performed using the integrative review method described by Whittemore and Knafl (2005), comprising problem identification, a literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation.

Search Methods

A preliminary search of CINAHL®, MEDLINE®, PubMed, and Google Scholar was conducted to ascertain relevant keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. The following search terms were used: compassion fatigue, burnout, secondary traumatic stress, secondary survivor, vicarious traumatization, countertransference, psychosocial interventions, strategy, plan, coping skills, treatment, coping strategies, self-care, support; and in-facility interventions; and in-facility psychosocial support interventions; and nurses, oncology nurses, hospice nurses, palliative nurses.

A systematic search of Cochrane Library, JBI Library, DARE, CINAHL®, PubMed, EBSCO Host, SABINET, and PsycINFO® was conducted to help define the MeSH terms. Information was retrieved from English literature published from 1992 to July 2015.

Eligibility Criteria

Selection criteria included English articles published in the past 25 years (compassion fatigue was first described in 1992) on in-facility psychosocial interventions or strategies for oncology nurses to manage burnout, secondary stress syndrome, secondary victimization, secondary traumatic stress, secondary survivor, vicarious traumatization, and compassion fatigue. Also included were quantitative and qualitative studies conducted in in-facility settings (i.e., hospitals, clinics, and hospices), as well as systematic, integrative, and thematic reviews. Searches also included studies of oncology nurses who may or may not have had specialist oncology training, hospice nurses, and palliative care nurses who worked full time (20–40 hours per week) in units or wards, outpatient chemotherapy units, inpatient adult and pediatric oncology wards, and hospices. Excluded were studies dealing only with other healthcare professionals and studies of interventions conducted outside of facilities.

An intervention was defined as a plan of action, program, or strategy aimed at addressing the psychosocial needs of oncology nurses to manage compassion fatigue and burnout. Psychosocial interventions of included studies were based within a healthcare facility and included any intervention focused on psychological or social factors rather than biologic factors. Psychosocial interventions could include health education, social support, stress relief, and physiologic elements, such as exercise (Aycock & Boyle, 2009).

Outcomes of the review measure the effectiveness, feasibility, and nurses’ experience of the interventions. The effectiveness of the interventions was measured by their success. The feasibility of the intervention was evaluated with an analysis of its use, cost-effectiveness, and necessary resources (including cost and time). Qualitative descriptions indicated whether the participants and the stakeholders were satisfied with the interventions.

Literature Search

Two reviewers independently screened the retrieved articles for eligibility. The initial search resulted in 164 articles, which were further examined by reviewers. One hundred and sixteen studies were excluded after an examination of the titles and abstracts. Of the 48 articles retained, 17 studies were excluded by the two researchers after a full-text assessment against inclusion criteria. Six of the remaining 31 were excluded because of methodology (opinion pieces and letters to the editor), with 25 articles remaining. A final search resulted in the addition of six studies. A total of 31 articles were included in the current review (see Figure 1).

Data Evaluation

Two reviewers independently appraised the studies. Any disagreements would have been discussed with a third reviewer, which was unnecessary. The quality of the qualitative studies was assessed using a rating system developed by Cesario, Morin, and Santa-Donato (2002), which has also been used by other reviewers (Maree & Schmollgruber, 2014). This tool assesses descriptive vividness, methodologic congruence, analytical preciseness, theoretical connectedness, and heuristic relevance.

The mixed-methods studies were assessed using the criteria outlined by O’Caithain, Murphy, and Nicholl (2008). The six categories evaluated in relation to these criteria were success of the study, mixed-methods design, quantitative component, qualitative component, integration, and inferences made.

The quality of quantitative articles was assessed using criteria proposed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project (2009) (i.e., selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and dropouts, intervention integrity, and analysis appropriate to question). The quality of the systematic reviews was assessed using Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (2015). These criteria included a priori design, duplicate study selection and data extraction, literature search, list of studies, scientific quality of the studies, methods for combining the findings of the studies, publication bias, and conflict of interest.

Data Synthesis

Data were extracted using the tool developed by Sparbel and Anderson (2000). The data extracted were author(s), journal, year, study design, methodology, participants, instruments, data collection, reliability, validity, analyses, interventions, outcomes, and the quality or level of evidence.

Search Results

A total of 164 publications were identified for potential inclusion in this review. Publications were found in Google Scholar (n = 43), PubMed (n = 36), CINAHL (n =49), PsycINFO (n = 19), and Web of Science (n = 17). Of the 164 publications, 139 were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria. The majority of publications were published in the United States (42%), followed by Europe (17%) and Canada (10%), among others.

Description of the Studies

A total of 31 publications were selected for final inclusion. Eight were qualitative studies, of which five were descriptive, two were explorative, and one was a case study on the formulation of an emotional safety policy. Fifteen were quantitative studies, of which two were randomized, controlled trials, five were quasiexperimental, and eight were nonexperimental/descriptive. Six were mixed-methods studies, and two were reviews (one systematic review and one thematic review).

Methods for collecting data included questionnaires (n = 22), interviews (n = 6), focus groups (n = 4), record reviews (n = 2), observation (n = 2), narrative writing, storytelling (n = 2), and anecdotal evidence (n = 1).

Questionnaires were the most common method for collecting data, followed by interviews and focus group discussions. The following questionnaires were used: Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) (n = 7, Dutch version and Turkish version), Link Burnout Inventory Questionnaire (LBI) (n = 1), Professional Quality of Life scale (ProQOL) (n = 4), team-building questionnaire (n =1), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (n = 1), Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (n = 1), Perceived Stress Scale (n = 1), Beck Depression Inventory (n = 1), Hogan Grief Reaction Checklist (n = 1), Inventory of Social Support (n = 1), Stress Self-Assessment Checklist (n = 1, Turkish version), Ways of Coping inventory (n = 1), nurses stress scale (n = 1), nurses coping with stress questionnaire (n = 2, one French version), and self-reported practice scale (n = 1). The majority of studies were conducted at single sites; only one study resulted from collaborative research between researchers from the United States and Israel.

Levels of evidence for the various studies were noted as follows. Levels of evidence for qualitative studies were either level QII: fair or level QIII: poor. Levels of evidence for quantitative studies were either moderate or weak. Mixed-methods studies were either fair or good, and the systematic review and thematic review were both of medium quality (see Table 1).

Purposive sampling was used for selection in all the studies. Sample sizes varied from 6–664 participants. The mean sample size was 94 for quantitative studies, 13 for qualitative studies, and 64 for mixed-methods studies. Participants in two studies included multidisciplinary oncology team members, and the number of oncology nurses was not indicated.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"31991","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"758","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"1061"}}]]

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"31996","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"758","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"1062"}}]]

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"32001","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"757","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"1063"}}]]

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"32006","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"756","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"1063"}}]]

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"32011","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"755","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"1060"}}]]

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"32021","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"759","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"1063"}}]]

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"32026","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"755","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"1062"}}]]

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"32031","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"758","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"1062"}}]]

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"32036","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"511","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"1062"}}]]

Effectiveness of In-Facility Interventions

To evaluate the effectiveness of the interventions, the current reviewers looked to see if any of the authors had conducted evaluations (e.g., pre-/post-test evaluations) showing an improvement in outcomes (i.e., a decrease in compassion fatigue or burnout). The systematic review identified 12 articles that reported interventions using multiple measurement tools. The outcomes reported in the systematic and thematic reviews were “variable and inconclusive” (Carton & Hupcey, 2014, p. 291).

Of 31 articles, four had not conducted an evaluation of the intervention, either because the studies were pilot studies and evaluations were still to be conducted, or because they were simple surveys consisting of open-ended questions. Nine studies showed that burnout had decreased.

Two studies showed that STSD and compassion fatigue decreased with the intervention (Potter et al., 2013; Saint-Louis, 2010); however, three studies reported that the interventions had no effects on compassion fatigue and burnout (Bruneau & Ellison, 2004; Hilliard, 2006; Moody et al., 2013). Reasons for interventions not showing any difference included preexisting high levels of burnout in participants who encountered additional stress in attending the intervention (Moody et al., 2013), participants not having time to practice relaxation skills learned in the intervention (Bruneau & Ellison, 2004), and the intervention not addressing the issues of compassion fatigue (Hilliard, 2006).

Four studies reported that general health (i.e., sleep and self-care) had improved (Carter et al., 2013; Edmonds et al., 2012; Houck, 2014; van Westrhenena & Fritz, 2013), and three studies reported that death anxiety and end-of-life stress had decreased after the intervention (Leung et al., 2012; Morita et al., 2007; Popkin et al., 2011). Two studies showed heightened team building, self-reflection, and camaraderie (Hilliard, 2006; Wittenberg-Lyles, Goldsmith, & Reno, 2014).

One study reported that the intervention had reduced the staff turnover rate from 12.5% to 7.5% during the fiscal year (Fetter, 2012). Single studies described benefits of learning of coping strategies, participatory approach to decision making, problem solving, and improving family and social life.

Experiences of In-Facility Interventions

Of the 31 studies, seven had not conducted an evaluation of the experiences by the participants. Eighteen studies showed that the participants were satisfied with the interventions, which they had found positive, useful, and enjoyable. Four studies noted that participants reported less stress after the intervention. Two studies reported that participants felt better able to offer emotional support to patients and relatives, and to accept grief and closure. Thirteen studies described participants’ experiences of rejuvenation, feelings of being appreciated, coping with job difficulties, and the value of peer support groups.

Themes identified in the thematic analysis were meaning, interventions and strategies, and commitment, which collectively contributed to effective coping. Meaning, in this context, referred to interventions that were shown to be successful and that reinforced self-reflection of one’s practice, which, in turn, created further enrichment of meaning (Zander & Hutton, 2009).

Feasibility of In-Facility Interventions

The current authors assessed the feasibility of interventions in all 31 articles. The timing and number of interventions varied, including one-off sessions (n = 5), retreats that lasted from four hours to one day (n =5), and multiple sessions (2–10) varying from three weeks to six months (n = 18). The studies included a wide range of interventions, and no program was predominantly featured. Content of interventions was extensive and diverse: relaxation (i.e., yoga and massage) was most used (n = 10), followed by self-care and self-reflection (n = 6) and emotional and experiential exchanges in small groups (n = 5). Other interventions included coping skills and stress management, role playing, debriefing, problem solving, bereavement care, journals, music therapy, sleep hygiene, mobile phone to cope with stress, play therapy, spiritual care, mindfulness, storytelling, short essays, humor, work–life balance, meaning of life, wellness plans, short films, psychodrama techniques, and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Studies reported barriers related to time constraints (n = 3), lack of funding (n = 1), nursing shortage (n = 1), and cancellation of intervention sessions (n = 1). One study acknowledged that no sustainability plan existed for the intervention. The majority of studies indicated that the interventions were useful, enjoyable, and satisfactory. Two studies described cultural diversity of participants and cultural acceptance of the intervention (Huggard & Nichols, 2011; van Westrhenena & Fritz, 2013). One study reported that financial constraints limited the rewards that could have been given in the intervention. Five studies acknowledged funding that was provided by scholarships, grants, or donations. Two studies proposed that policies were needed to support healthcare professionals in the prevention and management of burnout, which would make it easier to retain employees and increase employee productivity. The studies also recommended written policies on protective and preventive strategies to promote wellness and prevent burnout in employees. The majority of studies cited the need for management to promote or encourage group meetings or support groups to enhance personal resources for coping or to create a balance between professional and personal life, which would prevent or reduce compassion fatigue in oncology nurses.

Evaluations of feasibility in conducted studies took into account nurses’ satisfaction and, in a few cases, cost. Overall feasibility related to invervention use and integration into the health system was lacking.

Discussion

This integrative review was undertaken to increase the knowledge regarding in-facility interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nurses. The studies reviewed were predominantly from the United States, Europe, and Canada. Only four studies were published on interventions for compassion fatigue from 1992–2005. Twenty-seven studies were published on compassion fatigue interventions from 2006–2015. This increase in interest in managing compassion fatigue may be related to the books and articles on compassion fatigue written by Figley (1995, 2003, 2005).

Study Design

Thirteen quantitative studies were of weak quality because they were pilot studies, had small sample sizes, or had no randomization, no control groups, or no blinding, therefore limiting the potential for inferences and generalizability (Moody et al., 2013; Traeger et al., 2013). About half the interventions had a pre-/post-test design. The majority of qualitative articles were descriptive. Quantitative and qualitative studies failed to gain high scores in terms of quality. Activities or interventions were planned and conducted, and evaluations were conducted retrospectively (Fillion, Dupuis, Tremblay, De Grâce, & Breitbart, 2006; Medland et al., 2004; Popkin et al., 2011; Wittenberg-Lyles et al., 2014).

Bruneau and Ellison (2004) noted that, because of the enjoyable and helpful nature of the program, it would be problematic to limit entrance into the program. However, they also noted that the program did no harm.

Homogeneity of Participants

The homogeneity of oncology nurses (most were female) may compromise the validity of the review (Moody et al., 2013). Participation in the studies was predominately voluntary, and selection bias could have occurred because of the self-selection of participants who may have experienced work-related stress and hoped to find assistance from the study (Leung et al., 2012; Potter et al., 2013). Conversely, time demands of multisession activities may have overwhelmed participants and precluded participation (Potter et al., 2013). Other potential barriers to attendance, which could account for the small samples, include not being released from work to attend multisession interventions and financial restrictions (Macpherson, 2008; Traegar et al., 2013).

Heterogeneity of Study Interventions

The reviewed studies were heterogeneous, with a range of interventions producing knowledge on stress, burnout, compassion fatigue, and coping strategies among nurses. The interventions were not standardized; only four studies were directed by guidelines, and seven were guided by theoretical frameworks. Despite an absence of frameworks in the design of the interventions, interventions were clinically driven and informed by participants following needs analysis and preferences tailored to meet the nurses’ requests (Traeger et al., 2013). The majority of the studies reported on single interventions.

Moody et al. (2013) and Medland et al. (2004) proposed the inclusion of additional stress-reduction activities to establish a more robust intervention. Although quality ratings for the interventions tended to be low, all the articles emphasized the importance of recognizing and managing compassion fatigue, particularly in oncology nurses.

Heterogeneity of Outcomes

The majority of the studies used the standardized MBI or ProQOL instruments to assess compassion fatigue. However, evaluation was brief in some studies (Traeger et al., 2013). Seventeen studies showed pre- and post-test results that demonstrated some sustainability of the intervention.

A review of article authorship revealed that, in most cases, the authors confined their output to a single paper. Maree and Schmollgruber (2014) explained that research on cancer nursing tends to be a “fact-finding academic exercise” for qualification instead of research aimed at advancing health for patients with cancer and their families (para. 31).

Of the interventions that were evaluated for effectiveness, the majority showed a reduction in burnout, compassion fatigue, death anxiety, and staff turnover (Bruneau & Ellison, 2004; Lupo et al., 2012; Saint-Louis, 2010), which positively influenced patient care (Bruneau & Ellison 2004; Potter et al., 2013).

Participants reported satisfaction with the inter-ventions, that they learned effective coping skills, were better equipped to deal with intrusive thoughts, and had more positive feelings, making it easier for them to cope and lessening behavioral avoidance (Potter et al., 2013).

Only two of the studies were conducted in non-Western countries, suggesting the need for additional research in other countries to determine effective interventions that address compassion fatigue and stress cross-culturally (Carton & Hupcey, 2014; van Westrhenena & Fritz, 2013).

Most of the studies dealt with one-off interventions, and only a few of the interventions were conducted during an extended period of time. Successful interventions need to be conducted for longer periods for greater sustainability (Potter et al., 2013; Traeger et al., 2013). Several studies recommended institutional support to ensure that all participants were able to attend the interventions (Altounji, Morgan, Grover, Daldumyan, & Secola, 2013; Bruneau & Ellison, 2004; Lupo et al., 2012; Traegar et al., 2013).

Limitations

The current authors actively sought to access all related literature, but small samples in many of the studies limited the possibility of statistically documenting the entire impact of the intervention(s), limiting the scope for inferences and generalizability (Moody et al., 2013; Traeger et al., 2013). Interviews were conducted during short periods, and long-term effects were not explored (Leung et al., 2012). Almost half the articles reported a brief evaluation or no evaluation postintervention, which calls for further investigation to evaluate whether interventions (including one-off interventions) affectburnout, compassion fatigue, and STSD. Some interventions may have only short-term “feel good factors” (Le Blanc et al., 2007, p. 222). Limited conclusions can be drawn from the small studies that reported on outcomes with many confounding variables, such as turnover rate or general health of nurses, from a single institution. Although the current review focused on compassion fatigue, many research studies did not clearly distinguish between compassion fatigue and burnout. Therefore, the search terms of the current study included burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and vicarious traumatization.

Implications for Research

Additional research, including longitudinal control studies and studies on healthcare provider grief, is indicated (Carton & Hupcey, 2014; Wittenberg-Lyles et al., 2014). Lack of empirical precision in evaluating the effectiveness, feasibility, and nurses’ experience of the interventions indicates a need for future, more rigorously designed experimental studies. Most of the studies dealt with one-off interventions, with only a few of the interventions conducted during longer time periods, more of which is needed for greater sustainability (Potter et al., 2013).

Implications for Nursing

Compassion fatigue is a recognized issue in oncology. A number of related in-facility interventions have been carried out, but they have consisted of a variety of single, unevaluated interventions. The quality of many of the studies is weak; therefore, the evidence presented in this article does not advance the management of compassion fatigue. It could be of use, however, to researchers; educators, to promote compassion satisfaction; and administrators, to encourage coping among oncology nurses related to their professional and personal lives.

[[{"type":"media","view_mode":"media_original","fid":"32041","attributes":{"alt":"","class":"media-image","height":"211","typeof":"foaf:Image","width":"366"}}]]

Conclusion

The physical and emotional demands of the patient–nurse relationship, the oncology unit, and the daily challenges of nursing patients with cancer generate significant stress in oncology nurses (Gillespie, 2013; Potter et al., 2010). This integrative review identified 31 articles that provided insight into interventions seeking to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nurses.

The majority of interventions that were evaluated for effectiveness showed a reduction in burnout, compassion fatigue, death anxiety, and staff turnover. Most studies cited the need for management to promote or encourage group meetings or support groups to enhance personal resources for coping or to create a balance between professional and personal life that would prevent or reduce compassion fatigue in oncology nurses. Participants experienced rejuvenation, feelings of being appreciated, better coping with job difficulties, and the value of peer support groups.

About the Author(s)

Wentzel is a lecturer and Brysiewicz is a professor, both in the School of Nursing and Public Health at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Durban, South Africa. This research was funded by a grant (R24TW008863) from the Office of the U.S. Global AIDS Coordinator and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health (NIH OAR and NIH ORWH). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the government. Both authors contributed to the conceptual design, analysis, and manuscript preparation. Wentzel completed the data collection and provided statistical support. Wentzel can be reached at wentzel@ukzn.ac.za, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted July 2016. Accepted for publication September 20, 2016.

References

Absolon, P., & Krueger, C. (2009). Compassion fatigue nursing support group in ambulatory care gynecology/oncology nursing. Journal of Gynecologic Oncology Nursing, 19, 16–19.

Adams, R.E., Figley, C.R., & Boscarino, J.A. (2007). The compassion fatigue scale: Its use with social workers following urban disaster. Research on Social Work Practice, 18, 238–250. doi:10.1177/1049731507310190

Altounji, D., Morgan, H., Grover, M., Daldumyan, S., & Secola, R. (2013). A self-care retreat for pediatric hematology oncology nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 30, 18–23. doi:10.1177/1043454212461951

Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews. (2015). AMSTAR checklist. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/2omAua0

Aycock, N., & Boyle, D.A. (2009). Interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nursing. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 13, 183–191. doi:10.1188/09.CJON.183-191

Boyle, D.A. (2011). Countering compassion fatigue: A requisite nursing agenda. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 16, 2.

Bruneau, B.M., & Ellison, G.T. (2004). Palliative care stress in a UK community hospital: Evaluation of a stress-reduction programme. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 10, 296–304. doi:10.12968/ijpn.2004.10.6.13272

Carter, P.A., Dyer, K.A., & Mikan, S.Q. (2013). Sleep disturbance, chronic stress, and depression in hospice nurses: Testing the feasibility of an intervention [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40, E368–E373. doi:10.1188/13.ONF.E368-E373

Carton, E.R., & Hupcey, J.E. (2014). The forgotten mourners: Addressing health care provider grief—A systematic review. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 16, 291–303. doi:10.1097/NJH.0000000000000067

Cesario, S., Morin, K., & Santa-Donato, A. (2002). Evaluating the level of evidence of qualitative research. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecological and Neonatal Nursing, 31, 708–714. doi:10.1177/0884217502239216

Coetzee, S.K., & Klopper, H.C. (2010). Compassion fatigue within nursing practice: A concept analysis. Nursing and Health Sciences, 12, 235–243. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2010.00526.x

Delvaux, N., Razavi, D., Marchal, S., Brédart, A., Farvacques, C., & Slachmuylder, J.-L. (2004). Effects of a 105 hours psychological training program on attitudes, communication skills and occupational stress in oncology: A randomised study. British Journal of Cancer, 90, 106–114. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601459

Edmonds, C., Lockwood, G.M., Bezjak, A., & Nyhof-Young, J. (2012). Alleviating emotional exhaustion in oncology nurses: An evaluation of Wellspring’s “Care for the Professional Caregiver Program.” Journal of Cancer Education, 27, 27–36. doi:10.1007/s13187-011-0278-z

Effective Public Health Practice Project. (2009). Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/2oUNeYm

Emanuel, L., Ferris, F.D., von Guten, C.F., & von Roenn, J.H. (2011, June 6). Combatting compassion fatigue and burnout in cancer care. Retrieved from http://wb.md/2omoTrr

Fetter, K.L. (2012). We grieve too: One inpatient oncology unit’s interventions for recognizing and combatting compassion fatigue. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 559–561. doi:10.1188/12.CJON.559-561

Figley, C.R. (2003). Compassion fatigue: An introduction. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/2jC8hIV

Figley, C.R. (2005). Compassion fatigue: An expert interview with Charles R. Figley. Retrieved from http://wb.md/2nAZc9F

Figley, C.R. (Ed.). (1995). Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis Group.

Fillion, L., Dupuis, R., Tremblay, I., De Grâce, G.R, & Breitbart, W. (2006). Enhancing meaning in palliative care practice: A meaning-centered intervention to promote job satisfaction. Palliative and Supportive Care, 4, 333–344.

Giarelli, E., Denigris, J., Fisher, K., Maley, M., & Nolan, E. (2016). Perceived quality of work life and risk for compassion fatigue among oncology nurses: A mixed-methods study [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 43, E121–E131.

Gillespie, M.R. (2013). Compassion fatigue and cancer nurses: A national survey of cancer nurses in New Zealand [Master’s dissertation]. Eastern Institute of Technology, Taradale, New Zealand. Retrieved from http://repository.digitalnz.org

Girgis, A., Hansen, V., & Goldstein, D. (2009). Are Australian oncology health professionals burning out? A view from the trenches. European Journal of Cancer, 45, 393–399. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.029

Hilliard, R.E. (2006). The effect of music therapy sessions on compassion fatigue and team building of professional hospice caregivers. Arts in Psychotherapy, 33, 395–401.

Houck, D. (2014). Helping nurses cope with grief and compassion fatigue. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18, 454–458. doi:10.1188/14.CJON.454-458

Huggard, J., & Nichols, J. (2011). Emotional safety in the workplace: One hospice’s response for effective support. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 17, 611–617. doi:10.12968/ijpn.2011.17.12.611

Italia, S., Favara-Scacco, C., Di Cataldo, A., & Russo, G. (2008). Evaluation and art therapy treatment of the burn-out syndrome in oncology units. Psycho-Oncology, 17, 676–680. doi:10.1002/pon.1293

Kash, K.M., Holland, J.C., Breitbart, W., Berenson, S., Dougherty, J., Ouellette-Kobasa, S., & Lesko, L. (2000). Stress and burnout in oncology. Oncology, 14, 1621–1633.

Kravits, K., McAllister-Black, R., Grant, M., & Kirk, C. (2010). Self-care strategies for nurses: A psycho-educational intervention for stress reduction and the prevention of burnout. Applied Nursing Research, 23, 130–138. doi:10.1016/j.apnr.2008.08.002

Kushnir, T., Rabin, S., & Azulai, S. (1997). A descriptive study of stress management in a group of pediatric oncology nurses. Cancer Nursing, 20, 414–421.

Le Blanc, P.M., Hox, J.J., Schaufeli, W.B., Taris, T.W., & Peeters, M.C. (2007). Take care! The evaluation of a team-based burnout intervention program for oncology care providers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 213–227. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.213

Leung, D., Fillion, L., Duval, S., Brown, J., Rodin, G., & Howell, D. (2012). Meaning in bone marrow transplant nurses’ work: Experiences before and after a “meaning-centered” intervention. Cancer Nursing, 35, 374–381. doi:10.1097/NCC.0b013e318232e237

Lupo, F.N., Arnaboldi, P., Santoro, L., D’Anna, E., Beltrami, C., Mazzoleni, E.M., . . . Didier, F. (2012). The effects of a multimodal training program on burnout syndrome in gynecologic oncology nurses and on the multi-disciplinary psychosocial care of gynecologic cancer patients: An Italian experience. Palliative and Supportive Care, 11, 199–203. doi:10.1017/S1478951512000247

Macpherson, C.F. (2008). Peer-supported storytelling for grieving pediatric oncology nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 25, 148–163. doi:10.1177/1043454208317236

Maree, J., & Schmollgruber, S. (2014). An integrative review of South African cancer nursing research published from 2002–2012. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/2p3lFsO

McSteen, K.L. (2010). Compassion fatigue in oncology nursing: A witness to suffering. Oncology Nurse Advisor, 17–22.

Medland, J., Howard-Ruben, J., & Whitaker, E. (2004). Fostering psychological wellness in oncology nurses: Addressing burnout and social support in the workplace. Oncology Nursing Forum, 31, 47–54. doi:10.1188/04.ONF.47-54

Moody, K., Kramer, D., Santizo, R.O., Magro, L., Wyshogrod, D., Ambrosio, J., . . . Stein, J. (2013). Helping the helpers: Mindfulness training for burnout in pediatric oncology—A pilot program. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 30, 275–284.

Morita, T., Murata, H., Hirai, K., Tamura, K., Kataoka, J., Ohnishi, H., . . . Uchitomi, Y. (2007). Meaninglessness in terminally ill cancer patients: A validation study and nurse education intervention trial. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 34, 160–170. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.10.021

Najjar, N., Davis, L.W., Beck-Coon, K., & Doebbeling, C.C. (2009). Compassion fatigue: A review of the research to date and relevance to cancer-care providers. Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 267–277. doi:10.1177/1359105308100211

O’Caithain, A., Murphy, E., & Nicholl, J. (2008). The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 13, 92–98. doi:10.1258/jhsrp.2007.007074

Onan, N., Isıl, Ö., & Barlas, G.Ü. (2013). The effect of a new coping intervention on stress and burnout in Turkish oncology nurses. Journal of Marmara University Institute of Health Sciences, 3, 121–130. doi:10.5455/musbed.20130814120535

Popkin, K., Levin, T., Lichtenthal, W.G., Redl, N., Rothstein, H.D., Siegel, D., & Coyle, N. (2011). A pilot music therapy-centered grief intervention for nurses and ancillary staff working in cancer settings. Music and Medicine, 3, 40–46. doi:10.117/1943862110391471

Potter, P., Deshields, T., Berger, J.A., Clarke, M., Olsen, S., & Chen, L. (2013). Evaluation of a compassion fatigue resiliency program for oncology nurses. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40, 180–187. doi:10.1188/13.ONF.180-187

Potter, P., Deshields, T., Divanbeigi, J., Berger, J., Cipriano, D., Norris, L., & Olsen, S. (2010). Compassion fatigue and burnout: Prevalence among oncology nurses [Online exclusive]. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 14, E56–E62. doi:10.1188/10.CJON.E56-E62

Quinal, L., Harford, S., & Rutledge, D.N. (2009). Secondary traumatic stress in oncology staff. Cancer Nursing, 32, E1–E7. Sabo, B. (2011). Reflecting on the concept of compassion fatigue. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 16, 1.

Saint-Louis, N.M. (2010). A narrative intervention with oncology professionals: Stress and burnout reduction through an interdisciplinary group process [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Sparbel, K.J., & Anderson, M.A. (2000). Integrated literature review of continuity of care: Part 1, conceptual issues. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 32, 17–24. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2000.00017.x

Traeger, L., Park, E.R., Sporn, N., Repper-DeLisi, J., Convery, M.S., Jacobo, M., & Pirl, W.F. (2013). Development and evaluation of targeted psychological skills training for oncology nurses managing stressful patient and family encounters [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 40, E327–E336. doi:10.1188/13.ONF.E327-E336

van Rooyen, D., le Roux, L., & Kotzé, W.J. (2008). The experiential world of the oncology nurse. Health SA Gesondheid, 13(3), 18–30.

van Westrhenena, N., & Fritz, E. (2013). The experiences of professional hospice workers attending creative arts workshops in Gauteng. Health Education Journal, 72, 34–46. doi:10.1177/0017896911430545

Villani, D., Grassi, A., Cognetta, C., Cipresso, P., Toniolo, D., & Riva, G. (2012). The effects of a mobile stress management protocol on nurses working with cancer patients: A preliminary controlled study. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics, 173, 524–528. doi:10.3233/978-1-61499-022-2-524

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52, 546–553.

Wittenberg-Lyles, E., Goldsmith, J., & Reno, J. (2014). Perceived benefits and challenges of an oncology nurse support group [Online exclusive]. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18, E71–E76.

Zander, M., Hutton, A., & King, L. (2010). Coping and resilience factors in pediatric oncology nurses. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 27, 94–108. doi:10.1177/1043454209350154

Zander, M.A., & Hutton, A. (2009). Paediatric oncology nursing: Working and coping when kids have cancer—A thematic review. Neonatal, Paediatric, and Child Health Nursing, 12(3), 15–27.