Attachment Orientation and Relationships With Physicians and Nurses Among Israeli Patients With Advanced Cancer

Objectives: To examine the association between attachment orientation and relationships with physicians and nurses among Israeli patients with advanced cancer.

Sample & Setting: 52 patients with advanced cancer during active oncologic treatment.

Methods & Variables: Eligible patients who agreed to participate in the study completed the Experience in Close Relationships Scale, Working Alliance Inventory–Short Revised, and a list of topics, which were defined by the research team as central and common to patients’ coping.

Results: A correlation was found between avoidant attachment orientation and working alliance with nurses. In addition, patients’ attachment orientation was found to be correlated with the type of topics they chose to share with the staff.

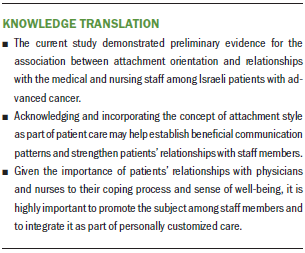

Implications for Nursing: Knowledge regarding the theoretical concepts of attachment orientation may assist nurses in providing tailored and beneficial communication patterns with patients.

Jump to a section

Relationships with medical and nursing staff have been found to be highly significant for the well-being and the coping process of patients with cancer (Halldorsdottir, 2008; Lelorain, Brédart, Dolbeault, & Sultan, 2012), particularly during advanced stages of the disease (Larson & Tobin, 2000). Open and direct communication with the staff was found to be related to reduced anxiety and a sense of comfort. In addition, it promoted understanding, trust, and agreement between patients and staff, thereby promoting adherence and better care (Li, Boquiren, Lo, & Rodin, 2011; Street, Makoul, Arora, & Epstein, 2009). The relationships between patients and staff can be defined and explored by the two theoretical concepts of working alliance and attachment style.

Working alliance (Bordin, 1979) is a concept from the field of psychotherapy that can be conceptualized as a specific aspect of the patient–staff relationship. The concept includes the following three elements (Bordin, 1979, 1980):

• Goals: Agreement and cooperation between the patient and caregiver regarding treatment goals

• Tasks: Agreement regarding the actions that need to be taken to accomplish treatment goals

• Emotional bond: Mutual liking and trust between the patient and caregiver

Working alliance in the medical context was found to be related to patients’ satisfaction, perceived competence of the medical staff, and adherence to treatment (Bennett, Fuertes, Keitel, & Phillips, 2011; Fuertes, Boylan, & Fontanella, 2009; Parchman, Zeber, & Palmer, 2010). Among patients with cancer, a strong working alliance with the medical staff was found to be related to high perceived social support and better coping with losses (Trevino, Fasciano, & Prigerson, 2013), to improved well-being at end-of-life stages (Zhang, Nilsson, & Prigerson, 2012), and to emotional acceptance of the terminal disease (Mack et al., 2009).

Another significant factor in patients’ coping is the attachment orientation. According to the theory of attachment style, a person’s attachment style begins to develop in the first year of life and is influenced by the nature of one’s relationship with his or her main caregivers. These relationships are internalized into models that embody the infant’s perception of the world and of him or herself, and from which adult behavioral styles are derived (Bowlby, 1988). Secure attachment is based on the belief that the world is a safe place and that other people will be available in times of need. It enables people to rely on and maintain social relationships during a crisis and to demonstrate constructive and flexible ways of coping with it. Anxious attachment refers to an overactivation of the attachment system. It includes intense efforts to maintain relationships with significant others who are perceived as distant, thereby causing the individual to worry about being rejected by them. Avoidant attachment refers to a subactivation of the attachment system. It includes efforts to avoid closeness and dependence in relationships with significant others because of a lack of trust and a need to maintain self-control (Bowlby, 1973, 1980; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2007). Attachment style usually is conceptualized by two dimensions, anxious and avoidant, with lower scores on each dimension reflecting a more secure orientation (Brennan et al., 1998).

From an emotional perspective, secure attachment can function as a buffer against the adverse effects of stressful events by using people’s high self-esteem and their ability to rely on social support (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2007). Among patients with cancer, secure attachment, which includes the sense that others will be available and supportive when needed, was found to be a significant factor in reducing stress (Lo et al., 2009) and depression (Lo et al., 2010), and was found to be related to post-traumatic growth (Schmidt, Blank, Bellizzi, & Park, 2012). Avoidant attachment was related to depression and reduced level of functioning, and anxious attachment was related to hopelessness and anxiety (Cicero, Lo Coco, Gullo, & Lo Verso, 2009; Porter et al., 2012).

Attachment orientation has been found to be related to the establishment of a good working alliance. People with secure attachment reported a stronger working alliance with their caregivers (Smith, Msetfi, & Golding, 2010). This correlation was found in the medical context as well. Patients with a secure orientation who were dealing with cancer had a better working alliance with their physicians (Calvo, Palmieri, Marinelli, Bianco, & Kleinbub, 2014), and patients with an insecure orientation demonstrated a lack of trust and satisfaction (Holwerda et al., 2013).

Given the importance of patient–staff relationships to patients’ coping and the significant role of attachment orientation, the authors decided to evaluate the association between attachment orientation and relationship with physicians and nurses among Israeli patients with advanced cancer. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this association has not been evaluated yet. This may increase understanding regarding patients’ interactions with the medical and nursing staff, particularly in the context of a life-threatening disease, and the factors that contribute to beneficial and communicative relationships. Specifically, the current study aimed to evaluate the following:

• The correlation between attachment orientation and working alliance with the medical and nursing staff among patients with advanced cancer

• The correlation between working alliance of patients with cancer and the type of topics they chose to share with the staff, assuming they would choose to share more personal issues with staff members to whom they feel closer

Methods

The research was carried out as a descriptive study. This design was selected because it is easy to implement as an initial evaluation, particularly among a population of patients with advanced cancer who may drop out because of various medical and emotional reasons.

Sample and Setting

The sample included patients with advanced cancer from the Department of Oncology at Rambam Health Care Campus in Haifa, Israel. The following were the inclusion criteria: 18 years of age or older, willingness to provide informed consent, ability to complete the study questionnaires, and Hebrew literacy.

Ninety-five patients were found to be eligible to participate in the study; 55 agreed to participate, 23 refused (because of physical weakness or other reasons), and 17 were disqualified because of language difficulties. From the patients who agreed to participate (n = 55), 52 completed all of the questionnaires and were included in the data analysis. No significant difference was found between patients who participated and those who did not (refused, disqualified, or did not complete all questionnaires) in the age variable (t[90] = –1.69). However, a difference was found in the gender variable (chi-square[1] = 4.79), with lower rates of women in the participant group than in the non-participant group (35% and 53%, respectively). No other comparison was performed to ensure the privacy of patients who did not consent to participate.

A power analysis revealed that, for an alpha of 0.05, the current sample size provided a power of 0.8 for medium effect size (Working Alliance Inventory [WAI] = 0.37) and a power of 0.9 for large effect size (WAI = 0.43).

Instruments

All participants completed an initial questionnaire, which included basic demographic items (e.g., gender, marital status) and medical questions (e.g., type of disease, stage of disease). The purpose of this questionnaire was to define the study’s sample and to examine possible differences in study variables because of these characteristics.

Working alliance: This variable was evaluated by WAI–Short Revised physician/nurse–patient version (Hatcher & Gillaspy, 2006; Munder, Wilmers, Leonhart, Linster, & Barth, 2010; Tracey & Kokotovic, 1989). This 12-item self-report questionnaire aims to evaluate the strength of the working alliance between patients and their physician or nurse. As mentioned previously, the theoretical model of Bordin (1979) described three components of the working alliance: goals (agreement regarding treatment goals), tasks (agreement regarding the actions needed to accomplish goals), and emotional bond (mutual liking and trust between the patient and caregiver). The questionnaire evaluates each scale of this model. The tool was found to be valid (r > 0.64) and reliable (alpha > 0.8) (Eveleigh et al., 2012; Hatcher & Gillaspy, 2006; Munder et al., 2010; Rotman, 1999). Several items were rephrased by the research team to better describe the medical context, similar to other studies (e.g., Pegman, Beesley, Holcombe, Mendick, & Salmon, 2011).

Attachment style: Attachment style was evaluated by the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR-M16) (Lo et al., 2009). This 16-item self-report questionnaire aims to evaluate a person’s attachment style. Its original version (ECR) includes 36 items rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1–7 (Brennan et al., 1998). It categorizes a person’s attachment style in romantic relationships according to two dimensions: avoidant and anxious. A score is calculated for each dimension. A low score on the two dimensions reflects a secure style. A high score on one of the dimensions reflects an anxious or avoidant style. Its modified version (ECR-M) was rephrased to refer to more general close relationships, rather than romantic ones, and was found to be validated among patients with advanced cancer (Lo et al., 2009). Its short version, which includes 16 self-report items (ECR-M16) (Lo et al., 2009), was found to be valid and reliable (p < 0.9), particularly among patients with advanced cancer (Lo et al., 2009; Philipp et al., 2017). In the current study, the short version was translated to Hebrew by the process of back translation to ensure as accurate a translation as possible (Shaw & Ahmed, 2004) and was based on a 10-item Hebrew version of the questionnaire, which was used in a previous study (Mikulincer & Florian, 2000).

Type of sharing: This variable was evaluated by a list of topics, which included 36 items divided into eight categories: fear of future suffering, concerns about the oncologic treatment, family members’ coping with the disease, symptom control, fear of death, use of complementary and alternative medicine, life expectancy, and integrating chemotherapy treatment with daily routine. These topics were selected as common issues with which patients with cancer deal, based on the authors’ experience in oncology. Patients rated the degree of sharing these topics with their physician or nurse during the past month on a scale of 1 (never) to 7 (always). In addition, they rated the frequency of thinking about these topics during the treatment period on the same scale. The last data were analyzed in a study by Bar-Sela et al. (2016).

Procedure

Health records of patients during active oncologic treatments were reviewed by the research team. Eligible patients were identified according to the inclusion criteria. The research team informed the relevant staff members (usually nurses) from the oncology division regarding these patients. During routine visits to the division as part of their treatment regimen, eligible patients were informed by staff members regarding the study. Patients who agreed to participate met the research coordinator, who explained in detail the study procedure and its questionnaires. The patients completed an informed consent form and the study’s questionnaires. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Rambam Health Care Campus.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was carried out with IBM SPSS Statistics, version 19.0. To reveal possible effects of the demographic and medical characteristics, analysis of variance was performed. Correlations between attachment orientation and working alliance with physicians and nurses was evaluated by Spearman (nonparametric) and Pearson (parametric) correlation. Because no significant differences were found between the two calculations, only Pearson correlation was reported, which is the more common measure. Correlation between working alliance and the type of topics discussed with the medical and nursing staff also was evaluated by Pearson correlation.

Results

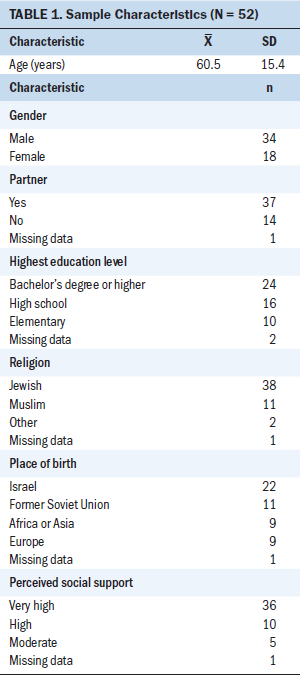

Fifty-two patients with advanced cancer completed the study. Most were male (n = 34) and Jewish (n = 38). Most had a partner (n = 37) and perceived their level of support as very high (n = 36). All patients were on active chemotherapy treatment, which lasted two to eight months. All demographic characteristics of the participants are detailed in Table 1.

No effect was found for the demographic variables, besides marital status. Patients in a relationship reported a stronger working alliance with their nurse in all its subscales, compared to single patients.

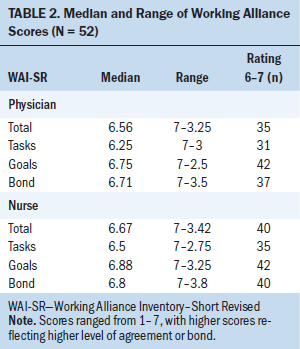

Participants reported high levels of working alliance, and more than half rated it as greater than 6 on a scale of 1–7 (see Table 2). These values were similar to those from previous studies with patients with cancer (Pegman et al., 2011) but higher than those of patients with less acute diseases, such as lupus (Bennett et al., 2011).

Regarding attachment orientation, the median score for anxious orientation was 2.4 (range = 1–6.5), with 69% of the patients on the lower range of the scale (1–3), reflecting a more secure pattern. The median score for avoidant orientation was 3.19 (range = 1–5.38), with 62% of the patients on the lower range of the scale. These values were similar to previous studies of patients with cancer (Fagundes, Jaremka, Malarkey, & Kiecolt-Glaser, 2014).

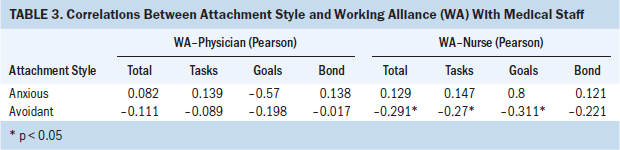

Correlations between attachment orientation and working alliance with the physician or nurse is shown in Table 3. No significant correlation was found in the anxious subscale. In the avoidant subscale, a significant correlation was found only with nurses, meaning that people who demonstrated a more avoidant attachment orientation had a weaker working alliance with the nurse.

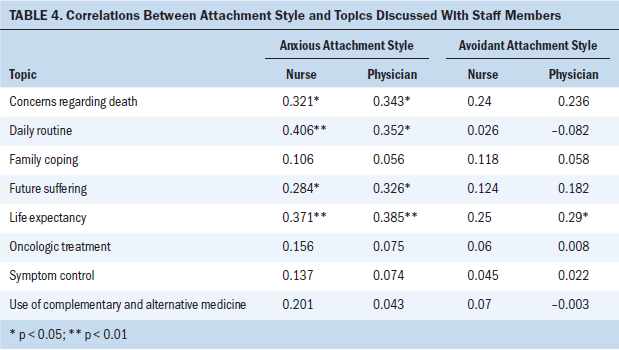

The correlation between attachment orientation and the type of sharing is detailed in Table 4. Anxious orientation was found to be related to the following topics: future suffering, concerns regarding death, life expectancy, and daily routine. Avoidant orientation was found to be related to life expectancy. In addition, avoidant orientation was found to be correlated close to significance in discussing life expectancy with nurses and concerns about death with physicians and nurses (p = 0.041, 0.048, and 0.045, respectively).

Discussion

The current study evaluated the association between patients’ attachment orientation and their relationships with the medical and nursing staff, as reflected in the working alliance and the type of topics they choose to share with them. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this issue has not been examined among patients with advanced cancer.

The current findings revealed a correlation between patients’ attachment orientation and working alliance with the staff; however, it was only significant among avoidant orientation and with nurses. This may be the result of the high levels of working alliance found in the study and the small variance in this variable, which made it difficult to find significant correlations with other variables. It also may be related to the process of coping with cancer, which can be traumatic and may mask temporally, or even permanently, personality patterns, including attachment orientation (Boulanger, 2002; Smith, Redd, Peyser, & Vogl, 1999). In addition, coping with a life-threatening disease may lead to increased dependence on the staff (Mechanic & Meyer, 2000; Seetharamu, Iqbal, & Weiner, 2007), resulting in higher levels of working alliance, as demonstrated in the current study. The finding that people with a more avoidant orientation had a weaker working alliance with the nurse can be interpreted as personality characteristics that are expressed more saliently with nurses, on whom patients feel less dependent. Specifically, for avoidant orientation, the expression is toward a more self-sufficient attitude and a distant relationship.

Finally, patients’ attachment orientation was found to be associated with the type of topics they chose to share with the medical and nursing staff. Anxious orientation was related to discussions about future suffering, concerns regarding death, life expectancy, and daily routine. Given anxious people’s tendency to perceive and interpret situations more negatively, to overactivate stress signals, and to be overoccupied with stress-evoking thoughts, it is likely that they need to share their concerns to reduce their distress and gain comfort. A person with a more secure orientation tends to cope more effectively, which may include turning to closer caregivers in times of need rather than the staff (Mikulincer & Florian, 2000).

Avoidant orientation was correlated to discussions about life expectancy with physicians. In addition, it was correlated close to significance to discussions about life expectancy with nurses and concerns regarding death with physicians and nurses. This means that these patients talked about difficult issues, unlike their usual coping strategy, which includes an emotional distance from any signs or thoughts related to stress (Halldorsdottir, 2008; Mikulincer & Orbach, 1995). This finding can be explained by patients’ direct and intense coping with death, which was found to be more difficult for avoidant people (Mikulincer, Florian, & Tolmacz, 1990). This situation challenges their regular strategies and makes them less effective. Suppressed thoughts and feelings are activated, and they turn to their caregivers for information. This act may help them regain a sense of control as they prepare themselves for the future to decrease dependency on others.

The results of this research should be approached with caution because of several limitations. First, the sample was relatively small. In addition, the data were collected by self-report questionnaires, with no observational tools and without taking the staff perspective into consideration. This may cause a positive bias because of patients’ difficulty in criticizing the staff and their desire to represent an ideal relationship with them. In addition, in a diverse and multicultural society, such as Israel, it is highly likely that the cultural aspect may have some influence on the findings. However, this was not evaluated in the current study.

Implications for Nursing

The finding of the current preliminary study may have important implications for nursing practice, which involves constant and direct interactions with patients as part of the daily routine work. Taking into account the theoretical concept of attachment orientation and acknowledging it as an integral part of their interactions with patients may promote nurses’ knowledge regarding emotional–interpersonal elements of personally customized treatment. It may assist them in better defining patients’ emotional needs and establishing more suitable communication patterns with them. This may promote patients’ sense of well-being and their adherence to their treatment.

Acknowledging these emotional elements is important, particularly in the current healthcare environment, which is characterized by an increased workload and fewer resources. In these conditions, nurses may be less concerned with the relational aspects of their routine care. However, considering these aspects is highly important and should be an integral part of nurses’ training and practice.

Conclusion

The current study provides partial support for the association between attachment orientation and relationships with the medical and nursing staff. These findings have implications regarding personally customized medical treatment for patients, which takes into account patients’ personality characteristics, in addition to genetic and clinical ones.

The current study may be useful in guiding nurses regarding the theoretical concept of attachment orientation, its dimensions, and expressions. Nurses will be able to recognize these aspects during their interactions with patients and to take them into consideration. Acknowledging these aspects by nurses may help promote a more beneficial communication, adjusted to patients’ needs. For example, patients with an avoidant orientation, who usually exhibit a more distant approach toward staff members, should be given encouragement to talk about their concerns.

Additional studies with larger samples and observational tools, rather than self-report measures, should further examine patient–staff interactions to evaluate ways to improve patient care and to adjust it to their needs, particularly when dealing with end-of-life issues. The impact of the staff’s attachment orientation on the communication patterns with patients should be evaluated as well. In addition, the cultural aspect should be examined to evaluate its effect on these communication patterns.

About the Author(s)

Gil Bar-Sela, MD, is the deputy director of the Division of Oncology at the Rambam Health Care Campus in Haifa; Rachel Gruber, MA, is a psychologist in the Department of Psychology at the University of Haifa; Inbal Mitnik, MA, is a medical psychologist and Doron Lulav-Grinwald, MA, is a clinical psychologist, both in the Division of Oncology at the Rambam Health Care Campus in Haifa; and Dan Koren, PhD, is the director of the clinical psychology program in the Department of Psychology at the University of Haifa, all in Israel. No financial relationships to disclose. Bar-Sela, Gruber, Lulav-Grinwald, and Koren contributed to the conceptualization and design. Bar-Sela, Gruber, Mitnik, and Koren completed the data collection. Bar-Sela and Koren provided statistical support and the analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. Bar-Sela can be reached at g_barsela@rambam.health.gov.il, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted January 2018. Accepted March 26, 2018.)

References

Bar-Sela, G., Yochpaz, S., Gruber, R., Lulav-Grinwald, D., Mitnik, I., & Koren, D. (2016). The association between the strength of the working alliance and sharing concerns by advanced cancer patients: A pilot study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 24, 319–325.

Bennett, J.K., Fuertes, J.N., Keitel, M., & Phillips, R. (2011). The role of patient attachment and working alliance on patient adherence, satisfaction, and health-related quality of life in lupus treatment. Patient Education and Counseling, 85, 53–59.

Bordin, E.S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 16, 252–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0085885

Bordin, E.S. (1980, June). Of human bonds that bind or free. Presidential address presented at the meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, Pacific Grove, CA.

Boulanger, G. (2002). Wounded by reality: The collapse of the self in adult onset trauma. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 38, 45–76.

Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss volume II: Separation, anxiety, and anger. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss volume III: Sadness and depression. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. London, England: Routledge.

Brennan, K.A., Clark, C.L., & Shaver, P.R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J.A. Simpson, & W.S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Calvo, V., Palmieri, A., Marinelli, S., Bianco, F., & Kleinbub, J.R. (2014). Reciprocal empathy and working alliance in terminal oncological illness: The crucial role of patients’ attachment style. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 32, 517–534.

Cicero, V., Lo Coco, G., Gullo, S., & Lo Verso, G. (2009). The role of attachment dimensions and perceived social support in predicting adjustment to cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 18, 1045–1052.

Eveleigh, R.M, Muskens, E., van Ravesteijn, H., van Dijk, I., van Rijswijk, E., & Lucassen, P. (2012). An overview of 19 instruments assessing the doctor–patient relationship: Different models or concepts are used. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 65, 10–15.

Fagundes, C.P., Jaremka, L.M., Malarkey, W.B., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. (2014). Attachment style and respiratory sinus arrhythmia predict post-treatment quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 23, 820–826.

Fuertes, J.N., Boylan, L.S., & Fontanella, J.A. (2009). Behavioral indices in medical care outcome: The working alliance, adherence, and related factors. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 24, 80–85.

Halldorsdottir, S. (2008). The dynamics of the nurse–patient relationship: Introduction of a synthesized theory from the patient’s perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 22, 643–652.

Hatcher, R.L., & Gillaspy, J.A. (2006). Development and validation of a revised short version of the working alliance inventory. Psychotherapy Research, 16, 12–25.

Holwerda, N., Sanderman, R., Pool, G., Hinnen, C., Langendijk, J.A., Bemelman, W.A., . . . Sprangers, M.A. (2013). Do patients trust their physician? The role of attachment style in the patient–physician relationship within one year after a cancer diagnosis. Acta Oncologica, 52, 110–117.

Larson, D.G., & Tobin, D.R. (2000). End-of-life conversations: Evolving practice and theory. JAMA, 284, 1573–1578.

Lelorain, S., Brédart, A., Dolbeault, S., & Sultan, S. (2012). A systematic review of the associations between empathy measures and patient outcomes in cancer care. Psycho-Oncology, 21, 1255–1264. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.2115

Li, M., Boquiren, V., Lo, C., & Rodin, G. (2011). Depression and anxiety in supportive oncology. In M.P. Davis, P.C. Feyer, P. Ortner, & C. Zimmermann (Eds.), Supportive Oncology (pp. 528–540). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Lo, C., Lin, J., Gagliese, L., Zimmermann, C., Mikulincer, M., & Rodin, G. (2010). Age and depression in patients with metastatic cancer: The protective effects of attachment security and spiritual wellbeing. Ageing and Society, 30, 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X09990201

Lo, C., Walsh, A., Mikulincer, M., Gagliese, L., Zimmermann, C., & Rodin, G. (2009). Measuring attachment security in patients with advanced cancer: Psychometric properties of a modified and brief experiences in close relationships scale. Psycho-Oncology, 18, 1045–1052. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1417

Mack, J.W., Block, S.D., Nilsson, M., Wright, A., Trice, E., Friedlander, R., . . . Prigerson, H.G. (2009). Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: The Human Connection Scale. Cancer, 115, 3302–3311. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24360

Mechanic, D., & Meyer, S. (2000). Concepts of trust among patients with serious illness. Social Science and Medicine, 51, 657–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00014-9

Mikulincer, M., & Florian, V. (2000). Exploring individual differences in reactions to mortality salience: Does attachment style regulate terror management mechanisms? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 260–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.2.260

Mikulincer, M., Florian, V., & Tolmacz, R. (1990). Attachment styles and fear of personal death: A case study of affect regulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.2.273

Mikulincer, M., & Orbach, I. (1995). Attachment styles and repressive defensiveness: The accessibility and architecture of affective memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 917–925. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.5.917

Munder, T., Wilmers, F., Leonhart, R., Linster, H.W., & Barth, J. (2010). Working Alliance Inventory-Short Revised (WAI-SR): Psychometric properties in outpatients and inpatients. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 17, 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.685

Parchman, M.L., Zeber, J.E., & Palmer, R.F. (2010). Participatory decision making, patient activation, medication adherence, and intermediate clinical outcomes in type 2 diabetes: A STARNet study. Annals of Family Medicine, 8, 410–417. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1161

Pegman, S., Beesley, H., Holcombe, C., Mendick, N., & Salmon, P. (2011). Patients’ sense of relationship with breast cancer surgeons: The relative importance of surgeon and patient variability and the influence of patients’ attachment style. Patient Education and Counseling, 83, 125–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.023

Philipp, R., Vehling, S., Scheffold, K., Grünke, B., Härter, M., Mehnert, A., . . . Lo, C. (2017). Attachment insecurity in advanced cancer patients: Psychometric properties of the German version of the Brief Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR-M16-G). Journal of Pain Symptom Management, 54, 555–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.026

Porter, L.S., Keefe, F.J., Davis, D., Rumble, M., Scipio, C., & Garst, J. (2012). Attachment styles in patients with lung cancer and their spouses: Associations with patient and spouse adjustment. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20, 2459–2466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1367-6

Rotman, A. (1999). Attachment styles in adulthood and the development of the working alliance [Master’s thesis; in Hebrew]. Department of Psychology, University of Haifa, Israel.

Schmidt, S.D., Blank, T.O., Bellizzi, K.M., & Park, C.L. (2012). The relationship of coping strategies, social support, and attachment style with posttraumatic growth in cancer survivors. Journal of Health Psychology, 17, 1033–1040. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105311429203

Seetharamu, N., Iqbal, U., & Weiner, J.S. (2007). Determinants of trust in the patient–oncologist relationship. Palliative and Supportive Care, 5, 405–409.

Shaver, P.R., & Mikulincer, M. (2007). Adult attachment strategies and the regulation of emotion. In J.J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 446–465). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Shaw, A., & Ahmed, M. (2004). Translating genetics leaflets into languages other than English: Lessons from an assessment of Urdu materials. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 13, 321–342. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOGC.0000035525.68249.52

Smith, A.E., Msetfi, R.M., & Golding, L. (2010). Client self rated attachment patterns and the therapeutic alliance: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.12.007

Smith, M.Y., Redd, W.H., Peyser, C., & Vogl, D. (1999). Post-traumatic stress disorder in cancer: A review. Psycho-Oncology, 8, 521–537.

Street, R.L., Jr., Makoul, G., Arora, N.K., & Epstein, R.M. (2009). How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Education and Counseling, 74, 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.11.015

Tracey, T.J., & Kokotovic, A.M. (1989). Factor structure of the working alliance inventory. Psychological Assessment, 1, 207–210.

Trevino, K.M., Fasciano, K., & Prigerson, H.G. (2013). Patient–oncologist alliance, psychosocial well-being, and treatment adherence among young adults with advanced cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 31, 1683–1689.

Zhang, B., Nilsson, M.E., & Prigerson, H.G. (2012). Factors important to patients’ quality of life at the end of life. Archives of Internal Medicine, 172, 1133–1142.