Treatment Decision-Making Involvement in Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer

Problem Identification: Involvement in treatment decision making (TDM) is considered a key element of patient- and family-centered care and positively affects outcomes. However, for adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer, little is known about the current state of knowledge about their perspective on and involvement in TDM or the factors influencing AYAs’ TDM involvement.

Literature Search: Integrative review focused on AYAs aged 15–21 years, their involvement in TDM, and factors influencing their involvement using the MEDLINE®, PsycINFO®, CINAHL®, and Web of Science databases.

Data Evaluation: 4,047 articles were identified; 21 met inclusion criteria.

Synthesis: Five factors were identified: AYAs’ preferred, actual, and perceived involvement; age and cognitive maturity; disease and illness factors; information and communication; and relationships, roles, and perspectives of parents and healthcare providers. AYA involvement in TDM varies depending on the magnitude and timing of the decision. AYAs’ role in decision making is situational and may evolve with time.

Implications for Research: Research is needed to understand AYAs’ preferences for TDM, the type and degree of their involvement, and the interactions between factors that contribute to or impede TDM.

Jump to a section

Although cancer survival rates generally have improved for pediatric and adult patients, survival rates for adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer have not kept pace. This lack of progress is most evident for those aged 15–25 years (Albritton et al., 2006; Bleyer, Ulrich, & Martin, 2012), who are confronted not just by cancer, but also by normal developmental challenges, the progression of which is affected by dependence on family and healthcare providers (HCPs), and by parental protectiveness (Coyne & Gallagher, 2011).

An important reason for the poorer outcomes in this age group is nonadherence to cancer treatment. Nonadherence rates as high as 60% have been reported (Alsous et al., 2017; Bhatia et al., 2014; Smith, Rosen, Trueworthy, & Lowman, 1979), which can lead to cancer relapse (Bhatia et al., 2015; Butow et al., 2010). Participation of AYAs in treatment decision making (TDM) may support adherence to medical treatment (Butow et al., 2010).

A core principle of patient- and family-centered care is empowering patients and families and building their confidence so they can make decisions about their health care (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012). AYAs with cancer are increasingly encouraged to be involved in TDM by organizations such as the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (Coccia et al., 2014). Professional organizations, government agencies, and ethical and legal perspectives promote the inclusion of children and adolescents in TDM. However, guidelines about when and how to involve children and adolescents in TDM are mostly opinion-based, with little empirical support, and evidence suggests they are infrequently followed (Unguru, Sill, & Kamani, 2010).

Understanding AYAs’ preferences is key to changing healthcare delivery to improve participation in decision making, satisfaction with the process of decision making, adherence to the therapeutic plan, and, ultimately, outcomes. To understand AYAs’ involvement in TDM and factors that influence how they approach TDM, the authors conducted an integrative review of the literature. Because most pediatric oncology units primarily care for patients aged 21 years or younger, in this review, the authors focused on the AYA age group (15–21 years). The aims of the review were to determine the following:

• The current state of knowledge about AYAs aged 15–21 years with cancer and their perspective on and involvement in TDM

• Factors influencing the AYAs’ TDM involvement, such as their age, developmental stage, and phase in the continuum of care

• Their TDM involvement within the context of their family and with their HCPs

Background

Cancer treatment for AYAs requires families to make challenging decisions throughout the disease trajectory, including at the time of diagnosis, during disease recurrence, during therapeutic changes, and at the time of end-of-life care (Stewart, Pyke-Grimm, & Kelly, 2012). Current recommendations are that children should be involved in decisions when they are able to do so and choose to participate (Joffe et al., 2006; Masera et al., 1997; Spinetta et al., 2003).

A key aspect of the phenomenon of AYA TDM is the triangular relationship among the patient, HCP, and parents. Parents sometimes assume a gatekeeper role, deciding what the child may be told to protect him or her from upsetting information (Young, Dixon-Woods, Windridge, & Heney, 2003). Stewart et al. (2012) reported variability in the degree to which parents involved their child in TDM. Parents focused on whether participation in TDM was in their child’s best interest, allowing more involvement in older children and less involvement when they prioritized sparing the child from distress.

Older children and AYAs commonly defer to parents or physicians for TDM for multiple reasons, including feeling pressured, wishing to avoid conflict, and deferring to others’ knowledge or experience (Knopf, Hornung, Slap, DeVellis, & Britto, 2008). HCPs may not be able to accurately estimate the cognitive development of AYAs and, therefore, their ability to participate in or understand issues related to TDM (Coyne & Gallagher, 2011). The imbalance of power between AYAs and parents and clinicians means that AYA participation in TDM is likely under external control. In a study of the attitudes of pediatric oncologists, de Vries, Wit, Engberts, Kaspers, and van Leeuwen (2010) found that some physicians do not believe adolescents are capable of meaningful participation, do not always provide adolescents with necessary information, and believe that proxy consent from parents is sufficient. However, the American Academy of Pediatrics (2012) policy statement advocating for patient- and family-centered care makes recommendations to support effective partnerships among children, parents and families, and HCPs.

When children and AYAs participate in TDM, they may benefit in multiple ways, including improved sense of control and autonomy and improved adherence to medical treatment (Barakat, Schwartz, Reilly, Deatrick, & Balis, 2014; Butow et al., 2010; Coyne, Amory, Kiernan, & Gibson, 2014; Coyne & Gallagher, 2011; Kelly, Mowbray, Pyke-Grimm, & Hinds, 2017; Ruhe, Badarau, et al., 2016; Snethen, Broome, Knafl, Deatrick, & Angst, 2006). Participation in TDM could be overly demanding (Ruhe, Badarau, et al., 2016). However, research results about why, how, and under what circumstances AYAs make cancer-related treatment decisions are unavailable. There are no reviews to the authors’ knowledge that examine the research literature as a whole to guide practice and further research on AYAs’ preferences and involvement in TDM or influencing factors.

Methods

Whittemore and Knafl’s (2005) methodology for conducting an integrative review served as the framework for this article. TDM was defined as decisions surrounding treatment or research aimed at curing or delaying cancer progression, or a decision about diagnostic, therapeutic, procedure, or supportive care choices. Older children were defined as ages 7–14 years.

A systemic search of the research literature was undertaken using the following databases: MEDLINE®, CINAHL®, PsycINFO®, and Web of Science. All databases were searched from their inception (PsycINFO, 1880; Web of Science, 1900; MEDLINE, 1946; CINAHL, 1981) through June 8, 2017. An initial scoping search led to the exclusion of Sociological Abstracts because it did not yield any unique, relevant articles. Reference lists of relevant articles were examined to find additional references. A combination of database index terms and keywords was used to ensure maximum recall of relevant articles, targeting three main concepts of the search: TDM, AYA age group, and childhood cancer. Non-English articles were excluded. The search strategy had three main concepts: cancer and related diseases; TDM, including patient participation and informed consent; and the AYA age group. Each concept was searched using a combination of database index terms and extensive keywords.

Articles identified by the search strategy underwent further screening according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The following inclusion criteria were used:

• Original quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses that included AYAs aged 15–21 years with cancer

• Studies that had a majority of participants with cancer if they included other chronic illnesses

• Procedures, methods, and analysis clearly described

• Studies that examined AYAs’ involvement in or perspective of TDM regarding their cancer treatment

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

• Studies limited to survivors or studies focused solely on fertility preservation

• Nonsystematic reviews, editorials, or case reports

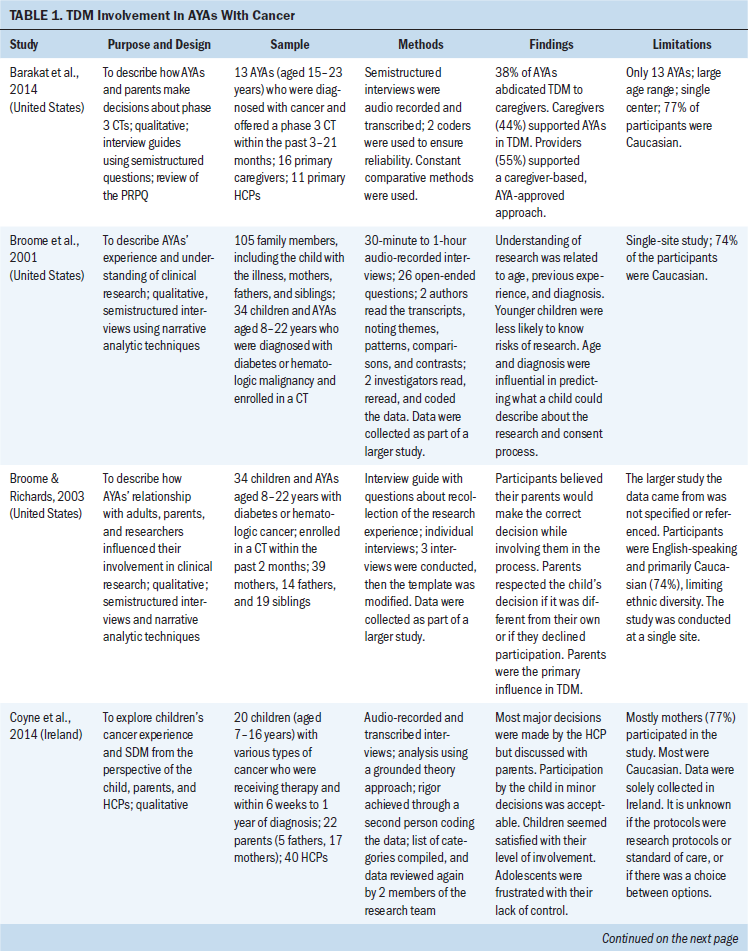

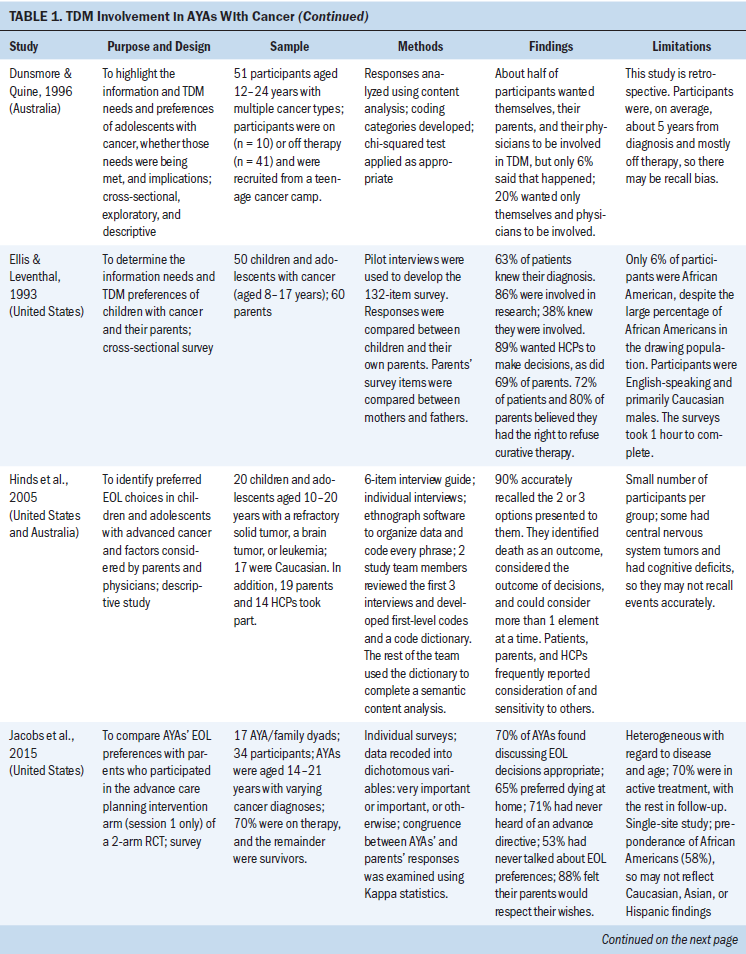

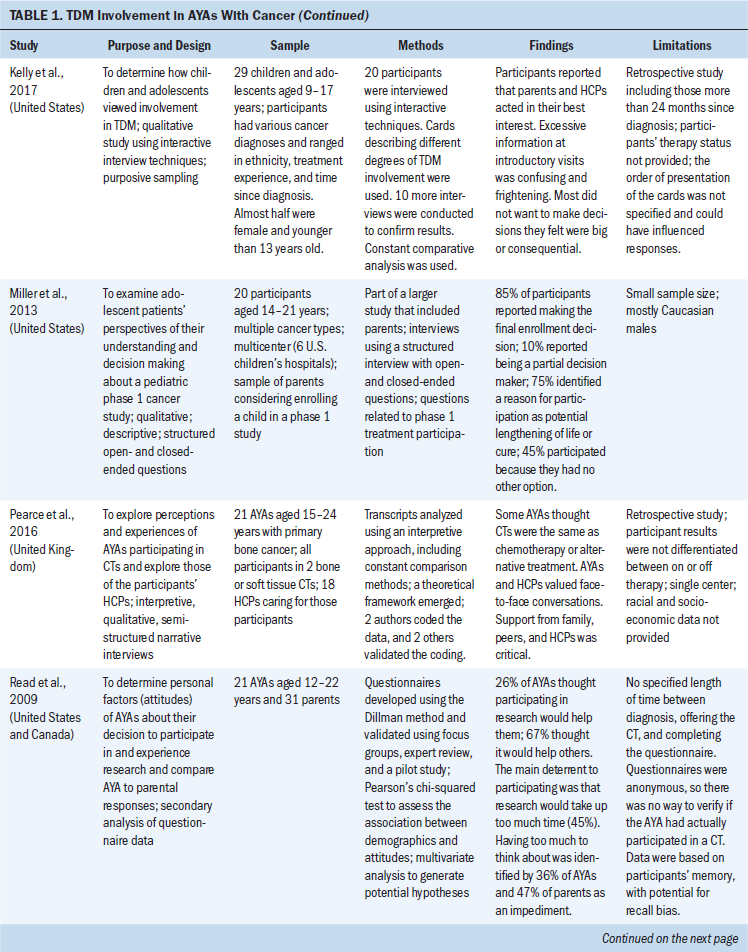

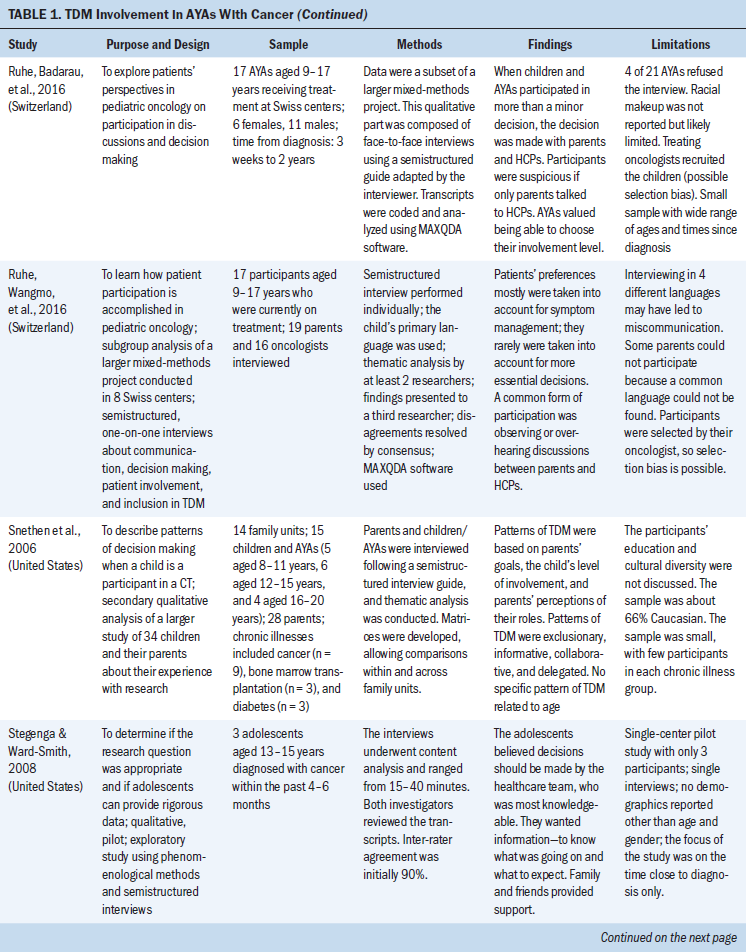

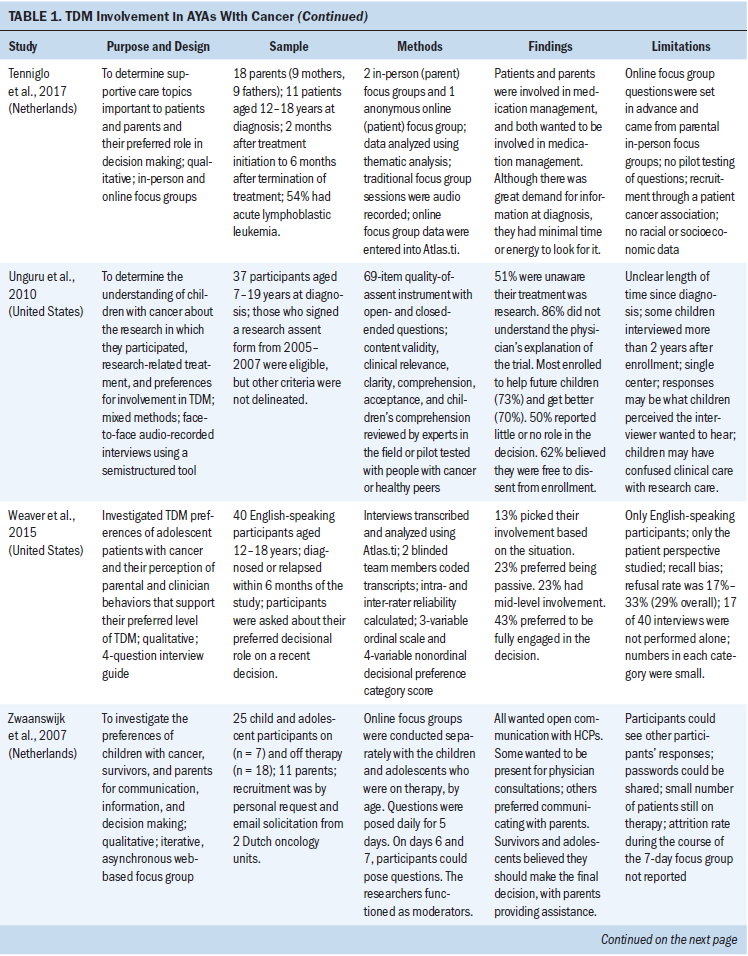

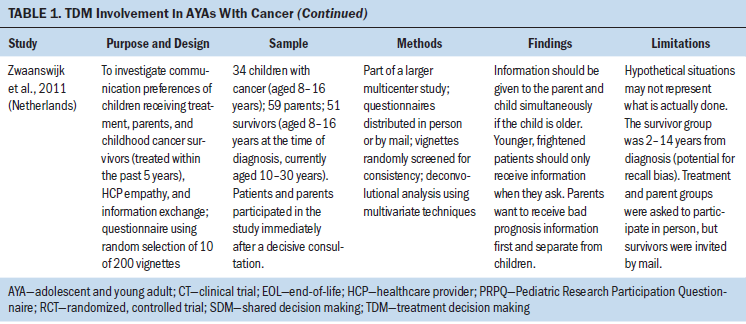

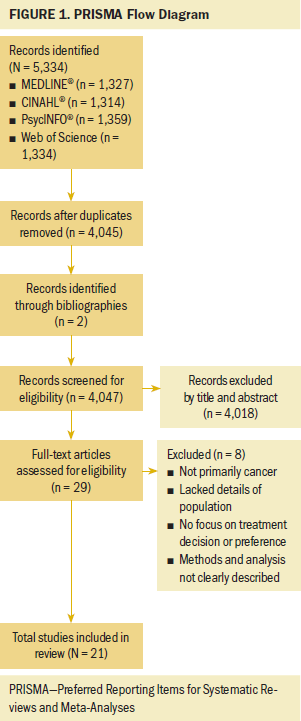

Data extraction included reviewing the articles for the purpose statement and description of design, sample characteristics, variables measured, data collection, analysis, main findings, and limitations (see Table 1). PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis) was used as a guide for reporting the studies (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009). Factors were identified to synthesize the findings. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to assess the methodological quality of the articles (Pace et al., 2012; Pluye, Gagnon, Griffiths, & Johnson-Lafleur, 2009). This tool allows analysis of multiple study types, including mixed methods; qualitative; randomized, controlled; nonrandomized; and observational descriptive. Articles are scored from 0–4, with 0 indicating no criteria met and 4 indicating all criteria met. Two of three authors (K.P.G., K.P.K., R.R.) scored each article using the MMAT. Differences of opinion were discussed until consensus was achieved. Data analysis entailed developing categories of findings and identifying important factors by collapsing similar results and comparing findings between studies.

Results

The search identified 4,047 possible studies. After removal of duplicates and further review of abstracts and full study reports in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 21 articles met the inclusion criteria and were selected for critical review: 15 were qualitative, and 6 were quantitative. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flowchart. Two articles were secondary data analyses. The years of publication ranged from 1993–2017. Two articles exclusively reported on AYAs (age 15–24 years), and 19 articles included children aged 14 years and younger in addition to the target group of AYAs. Across the 21 studies, age ranged from 7–24 years. The studies took place in the United Kingdom (n = 2), the Netherlands (n = 3), Switzerland (n = 2), Australia (n = 2), Canada (n = 1) and the United States (n = 13). Two of the 21 studies were multisite and conducted in two different countries. The 21 studies included participants who were receiving treatment for cancer, no longer receiving therapy (survivors), or diagnosed with a different chronic illness. The types of decisions described in the studies were primarily related to research participation (phase 1, 2, or 3 trials) (n = 8), end-of-life decisions in which there may have been an option to participate in a phase 1 clinical trial (n = 2), and TDM in general (i.e., at diagnosis, treatment, relapse, and supportive care) (n = 11).

The MMAT study quality scores ranged from 2–4 (0–4 scale). Three studies were assessed to be of high quality (score = 4), 15 as moderate quality (score = 3), and 3 as lower quality (score = 2). All 21 studies were included so as to be comprehensive in examining the scope and depth of the phenomenon (Noblit & Hare, 1988).

The following five major factors were identified from the 21 studies, reflecting the AYAs’ involvement in TDM or influencing factors:

• AYAs’ preferred, actual, and perceived involvement

• Age and cognitive maturity

• Disease and illness factors

• Information and communication

• Relationships, roles, and perspectives of parents and HCPs

The factors relate to the degree of involvement in TDM (factor 1) and those influencing TDM (factors 2–5).

Preferred, Actual, and Perceived Involvement

Older children and AYAs with cancer did not always participate in TDM at their level of preference and comfort (Unguru, 2011; Zwaanswijk et al., 2007), and they varied in their preference for involvement in TDM, from none at one end of the spectrum, to making most of the decisions at the other. No matter the AYA’s role in decision making, the family was usually involved to some extent.

Responses ranged from completely deferring decision making to others, to independently making decisions. In 3 of the 21 studies, older children and AYAs described how they preferred to have their physician or parents decide about their treatment (Ellis & Leventhal, 1993; Stegenga & Ward-Smith, 2008). Ellis and Leventhal (1993) reported that most wanted the physician to make all decisions. Some older children and AYAs believed there was no real decision to make because the only choice was to proceed with life-saving therapy (Coyne et al., 2014). Similarly, Barakat et al. (2014) found that the majority of AYAs had little or no role in TDM about phase 3 clinical trials. Unguru et al. (2010) also reported that older children and AYAs perceived they had little or no role in the decision to participate in research. Five studies identified older children and AYAs’ preference to collaborate with their parents and providers (Dunsmore & Quine, 1996; Kelly et al., 2017; Ruhe, Badarau, et al., 2016; Unguru et al., 2010; Zwaanswijk et al., 2011); most wanted to be informed (Zwaanswijk et al., 2007) but did not want the sole responsibility for making decisions (Dunsmore & Quine, 1996; Unguru et al., 2010).

Some older children and AYAs preferred to be or were fully engaged in the decision (Weaver et al., 2015) or made the final decision with parental assistance (Zwaanswijk et al., 2007). Two studies reported that older children and AYAs wanted to be either more informed or more involved than they actually were in decision making (Dunsmore & Quine, 1996; Unguru et al., 2010). Having autonomy in decision making related to clinical trials was very important to most AYAs in a study conducted by Pearce et al. (2016). In seven articles, altruistic motives were a reason for participating in clinical research (Barakat et al., 2014; Broome, Richards, & Hall, 2001; Hinds et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2013; Pearce et al., 2016; Read et al., 2009; Unguru et al., 2010).

Investigators reported situations when older children and AYAs did not want to assume responsibility for making the decision, such as at or close to the time of diagnosis (Stegenga & Ward-Smith, 2008; Weaver et al., 2015). At diagnosis, there was often an urgency to start treatment while older children and AYAs were too ill to participate in discussions or decision making (Barakat et al., 2014; Zwaanswijk et al., 2007). There were also situations when they did not want to surrender the control of TDM, such as at the end of life (Hinds et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2013). Barakat et al. (2014) reported that AYAs recalled minimal or no role in clinical trial TDM, although their parents recalled substantial efforts to involve the AYAs. AYAs and parents had markedly different memories of the same event, and AYAs experienced regret for not being as involved as they would have preferred.

Age and Cognitive Maturity

Eight studies reviewed showed that age and cognitive maturity were factors influencing whether older children and AYAs were involved in TDM. Five studies reported that increased age and maturity was associated with increased decision involvement (Barakat et al., 2014; Coyne et al., 2014; Ellis & Leventhal, 1993; Unguru et al., 2010; Zwaanswijk et al., 2011). Unguru et al. (2010) reported that age was associated with the types of decisions, roles performed, and physicians’ willingness to discuss decision making, with older children being more likely to be involved in TDM. In the study by Zwaanswijk et al. (2011), parents, patients, and survivors uniformly recommended that children (aged younger than 12 years) not be involved in TDM (odds ratio [OR] = 0.1, confidence interval [CI] [0.0, 0.2]), but preferred that adolescents (older than 12 years) be involved (OR = 18.2, CI [6.8, 48.4]). Patient age was the main factor associated with information and preferences to participate in decision making. Ellis and Leventhal (1993) found that older children and AYAs believed that the patient should be aged at least 16 years to participate in making minor treatment decisions. Barakat et al. (2014) reported that cognitive and emotional maturity facilitated involvement in phase 3 clinical enrollment decisions.

In contrast, several studies showed that age was not associated with family decision-making patterns, such as exclusionary, informative, collaborative, and delegation (Snethen et al., 2006). Weaver et al. (2015) also found no correlation between age, time on treatment, new or relapsed disease, and decision-making preference, although their study consisted of only 40 participants. In their study of 51 older children and AYAs with cancer, Dunsmore and Quine (1996) found that age was not correlated with decision making.

It was not possible to determine from the studies if preferences for TDM were based on age, experience with cancer and cancer treatment, or other factors. Younger patients may have been diagnosed with cancer for a longer period of time than older, recently diagnosed AYAs, so they may have acquired experience beyond their years.

Disease and Illness Factors

Fifteen articles reported findings relating older children and AYAs’ disease and illness factors to TDM involvement. Their symptoms, the seriousness of the condition, and the urgency of the decision were barriers to their participation in TDM (Barakat et al., 2014; Broome et al., 2001; Zwaanswijk et al., 2007). Prognosis also determined whether older children and AYAs were included in TDM. Parents did not want them to participate if they had a moderate (OR = 0.5) or unclear (OR = 0.2) prognosis (Zwaanswijk et al., 2011). Barakat et al. (2014) highlighted acute emotional or physical stress as a limiter of AYAs’ involvement and participation in decision making. These studies demonstrate that the emotional or physical state of older children and AYAs can influence the actual TDM role they assume.

Additional factors influenced older children and AYAs’ choice or actual participation in TDM. They classified decisions as minor (delivery of care, decisions about pain management and antiemetics) or major (decisions about treatment protocols) (Coyne et al., 2014; Ruhe, Wangmo, et al., 2016; Tenniglo et al., 2017). They also considered major decisions not to be decisions at all because there was only one obvious choice and refusal was not an option (Coyne et al., 2014). Decision-making involvement was situational; older children and AYAs preferred to participate in minor or supportive care decisions if they felt well but left most major decisions to the HCP (Ruhe, Wangmo, et al., 2016; Weaver et al., 2015). Kelly et al. (2017) also reported that most older children and AYAs did not want to make big decisions.

TDM involvement was often dependent on the stage in the disease trajectory. In one study by Miller et al. (2013), 85% of older children and AYAs reported they made the final decision about a phase 1 cancer study. They had all experienced the standard diagnosis and management, so they would be classified as experienced, no matter their chronological age. Other researchers found decision making shifted from the parents or HCP to older children and AYAs later in the disease trajectory (Hinds et al., 2005).

Information and Communication

In 17 studies, older children, AYAs, and families referred to information seeking, information exchange, and communication with the healthcare team in the context of decision making. Limited knowledge of the disease and treatment were important barriers to participation in decision making (Coyne et al., 2014; Stegenga & Ward-Smith, 2008; Zwaanswijk et al., 2007). Ellis and Leventhal (1993) found that, although most older children and AYAs with cancer wanted the doctor to make all decisions, those who had less understanding of their diagnosis were less likely to want to be involved in making decisions than those with more understanding (p = 0.039). Alternatively, Coyne et al. (2014) reported that adolescents identified receiving information as an important determinant of their participation in shared decision making, and that they were unsatisfied with their participation in decision making, claiming they were limited by parents and HCPs. Ruhe, Wangmo, et al. (2016) found that parents actively limited information that could be upsetting or related to prognosis, thereby limiting the knowledge older children and AYAs needed to participate in TDM.

In Zwaanswijk et al.’s (2011) study, 60% of older children and AYAs felt it was important to receive information even if they did not want it at the time. They also thought the patient should participate in medical decision making. Pearce et al. (2016) reported that AYAs thought effective communication, information availability, and the opportunity to ask questions were important for them to participate in trials. A trusting relationship with their HCPs allowed for good communication and encouraged trial participation.

In contrast, Stegenga and Ward-Smith (2008) found that receiving information and being informed was important to older children and AYAs, but not necessarily linked to decision making. They studied adolescents within six months of diagnosis, finding that their desire for information was not a desire for control but simply a desire to understand; they believed the healthcare team should make the decisions.

Relationships, Roles, and Perspectives

Eighteen studies discussed how the relationship or role of the parent or HCP influenced older children and AYAs’ involvement in TDM. Ruhe, Wangmo, et al. (2016) reported that physicians and parents regulate older children and AYAs’ participation in decision making. They sometimes controlled the amount, type, and timing of information given to the child.

The most frequently reported factor by older children and AYAs, parents, and physicians in making decisions was consideration of and sensitivity to others (Hinds et al., 2005). They relied on their parents to protect them and trusted them to make decisions in their best interests (Broome & Richards, 2003). They trusted HCPs because they assumed they were experts (Coyne et al., 2014). They wanted support or preferred shared decision making with family and clinicians (Coyne & Gallagher, 2011; Zwaanswijk et al., 2007).

Snethen et al. (2006) described four family patterns of decision making in the context of clinical trials. Parents whose goal was to protect older children and AYAs and excluded them from participation in TDM were identified as exclusionary. Parents who preferred to have their older children and AYAs understand the issues and the meaning of the decisions were identified as informative. Parents whose children tended to be older compared to the members of other groups and who advocated active participation by AYAs were identified as collaborative. Finally, parents who approved the choice to be made but turned over the actual decision to the AYAs were identified as delegators.

Collectively, these findings highlight the complexity of the triadic relationship among the provider, parent, and AYAs. Their involvement in TDM was related to many variables, including age, experience with illness, and their progress along the continuum of care.

Discussion

The findings from these studies demonstrate that, for older children and AYAs, their actual TDM involvement varies based on their chronological and developmental stage, disease state, previous experience with disease, type and magnitude of the decision, and decisional and family context. Preferences for their level of involvement in TDM varies during cancer treatment for many reasons (e.g., stage of illness, seriousness of condition, type of decision); therefore, participation appears to be an ongoing process that varies with the situation (Coyne & Harder, 2011).

Even though the findings included older children, the discussion will focus on how they pertain to AYAs. In this integrative review, five factors were identified about AYAs’ involvement in or perspectives of TDM regarding their cancer treatment. Treatment decision making is situational because AYAs are comfortable making some decisions but not others; parents and HCPs have varying degrees of involvement. Decisions that AYAs are more comfortable with include minor decisions about care delivery (Coyne et al., 2014), whereas for decisions of tremendous consequence, such as those at the time of diagnosis, they are more likely to defer to their parents or providers.

Decision making is a process that evolves during an AYA’s disease trajectory. AYAs enter the illness journey with little or no understanding of their disease, with their experiences providing a rapid education. Later in the course of the disease, when many of these AYAs experience complications and face a decision about alternative treatment or end-of-life care, they have become knowledgeable and more assertive about their involvement in decision making (Bluebond-Langner, Belasco, & DeMesquita Wander, 2010; Hinds et al., 2005; Lyon, McCabe, Patel, & D’Angelo, 2004; Miller, 2009; Miller et al., 2013; Miller & Harris, 2012; Miller, Reynolds, & Nelson, 2008).

Early in the disease trajectory, the degree of involvement by AYAs in their own TDM is determined primarily by the attitudes of the HCPs and parents, not by the AYA’s ability (Coyne, 2008; Martenson & Fägerskiöld, 2008). Even when AYAs are competent to make treatment decisions, they still want support and prefer shared decision making with family and clinicians (Coyne & Gallagher, 2011; Pearce et al., 2016; Zwaanswijk et al., 2007).

This review identified contradictory findings regarding the association of age with TDM. Bluebond-Langner et al. (2010) argued that relying on chronological age or developmental stage to determine how to involve young people with cancer in decision making is unreliable because of the marked inter-individual differences in rate and stage of development and treatment experience. Recently diagnosed patients—no matter what age—may still be in the passive, early state of decision making. If they are experiencing substantial suffering or stress, even the most mature adolescents are likely to rely on relatives or other proxy decision makers (de Vries et al., 2010). In a systematic review, Day, Jones, Langner, and Bluebond-Langner (2016) also reported that adolescents’ ability to participate in TDM and discussions, as determined by their HCP, is determined by their maturity or disease experience and not their age. In the studies reviewed, researchers did not provide information about the distribution of experience of their samples, so this interaction cannot be identified. Future studies must assess the complexity of the patient experience in addition to the participants’ chronological age.

How information is provided and the degree to which parents and HCPs directly communicate with AYAs is an important factor in determining involvement in and experience of TDM (Stegenga & Ward-Smith, 2008; Zwaanswijk et al., 2007). For some, receiving information and communication defines their level of involvement in decision making. For adolescents, lack of information is a barrier to active decision making. Adolescents living with chronic illness value clear and straightforward technical information (Britto, Cote, Horning, & Slap, 2004; Britto et al., 2007; Dunsmore & Quine, 1996; Knopf et al., 2008). Less than 20% of adolescents preferred patient-led decision making; the majority do not want to direct decision-making authority or make the final decision (Britto et al., 2004; Knopf et al., 2008). Knopf et al. (2008) suggested this may be because of their recognition of how complex and life-threatening the decisions really are. This finding is supported by Kelly et al. (2017), who suggested that, during cancer treatment, older children and AYAs may prefer information exchange and communication to being involved in actually making treatment decisions.

TDM is not one-dimensional. The findings suggest there is an interaction among age, previous cancer experience, and decision making. Studies support the finding that TDM patterns change with time and as individuals become experienced with their disease. Many of these studies examine characteristics of AYAs or decision making in one dimension, rather than identifying the many factors that modify the situation. For instance, an 18-year-old who is newly diagnosed with cancer may be naive, but a 10-year-old may be very experienced, having lived with cancer for the past five years. Important dimensions that must be considered in studying or advocating for AYA involvement in TDM include age, the normal developmental progression of AYA decision making, experience with the illness, low-risk decisions versus high-risk decisions, and decisions with a clearly identified best option versus no best option.

Any effort to involve AYAs in TDM must take into account the parents’ perspectives and their role in the care and treatment of their children. Bluebond-Langner et al. (2010) reported that parents feel strongly that the responsibility for the decision rests with them. More research is needed to determine how AYAs with cancer interact with their family to make treatment decisions (e.g., how each negotiate their roles, given findings suggesting that decision making by AYAs and their family is a dynamic, social process).

Limitations

The findings of this integrative review should be considered in light of several limitations. For example, most of the included studies involved participants who were younger and older than the target AYA age range. Because most of these studies did not report findings for subsamples, it was not possible to determine how the reported results were similar or different with respect to age or condition. Another limitation was the lack of consistency in how TDM was defined, making it challenging to interpret and compare findings across studies. Many of the studies were retrospective, with participant recall of their TDM experiences, potentially leading to recall bias. Other methodological concerns included weaknesses across methods (i.e., whether quantitative studies had adequate sample sizes and whether qualitative studies were conducted with adequate rigor). Finally, most of the studies had inadequate representation of minority groups.

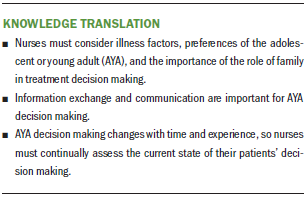

Implications for Nursing

The findings of this integrative review provide nurses with a comprehensive summary of the state-of-the-science with respect to AYAs’ experience of TDM and influencing factors. In caring for AYAs, nurses must consider multiple factors, such as age, disease, treatment trajectory, and relationships with parents and HCPs when encouraging AYAs to participate in decision making. Nurses must also be mindful that the AYAs’ role in TDM may be situational and evolve with time to become more active. Recognizing the role of family in TDM is essential. This information could be incorporated into a teaching curriculum for HCPs of AYAs who have cancer or used to develop an assessment tool for AYA decision making.

Future research investigating understanding of AYAs’ voice and preferences for TDM, the actual involvement of AYAs in the decision-making process, and the interactions among factors that contribute to or impede this process is warranted. Studies including relevant outcomes of TDM participation are lacking, particularly related to congruence between desired and actual TDM roles. Important next questions include the following:

• How do AYAs want to be involved in TDM?

• In what types of decisions do AYAs want to be involved?

• How do AYAs negotiate their role and involvement in decision making?

• When does a transition of decision-making authority take place from the parents to the AYAs?

Conclusion

The findings of this review suggest that AYAs’ role in decision making evolves with time to become more active but is situational. The findings highlight the importance of the role of family and relationship with the HCP throughout their continuum of care. Barriers and facilitators to shared TDM include the AYAs’ preferences, age, disease, and relationships with family and providers. Involvement in decision making can be particularly challenging for AYAs with cancer because of their diagnosis of a chronic, potentially life-threatening illness, family influence, developmental stage, and desire to transition to an independent young adult. Additional research would help to identify important areas to focus interventions, in turn moving forward the science directed to the care of AYAs with cancer.

About the Author(s)

Kimberly A. Pyke-Grimm, PhD, RN, CNS, is a clinical nurse specialist and nurse scientist at the Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford in Palo Alto, CA; Linda S. Franck, PhD, RN, FAAN, is a professor in the School of Nursing and Department of Family Health Care Nursing at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF); Katherine Patterson Kelly, PhD, RN, is a nurse scientist in the Department of Nursing Science, Professional Practice, and Quality at the Children’s National Health System in Washington, DC; Bonnie Halpern-Felsher, PhD, FSAHM, is a professor in the Department of Pediatrics at Stanford University in California; Robert E. Goldsby, MD, is a professor of clinical pediatrics at the UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital in California; Ari Kleiman, MLIS, is a clinical research librarian at the UCSF Medical Center Institute for Nursing Excellence in California; and Roberta S. Rehm, PhD, RN, FAAN, is a professor in the School of Nursing and Department of Family Health Care Nursing at UCSF. This research was funded by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (F31 NR015951) from the National Institutes of Health and National Institute of Nursing Research and a predoctoral award from the American Cancer Society. Franck has previously consulted for Proctor and Gamble. Kelly has previously consulted for the GetWell Network. Rehm has previously received support from the International Family Nursing Association. Pyke-Grimm, Franck, Halpern-Felsher, Goldsby, and Rehm contributed to the conceptualization and design. Pyke-Grimm, Kelly, and Kleiman completed the data collection. Pyke-Grimm provided statistical support. Pyke-Grimm, Franck, Kelly, Halpern-Felsher, and Rehm provided the analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. Pyke-Grimm can be reached at kpykegrimm@stanfordchildrens.org, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted April 2018. Accepted July 4, 2018.)

References

Albritton, K., Caligiuri, M., Anderson, B., Nichols, C., Ulman, D., Adams, H., . . . Zebrack, B. (2006). Closing the gap: Research and care imperatives for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Report of the Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Progress Review Group. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/types/aya/research/ayao-august-2006.pdf

Alsous, M., Abu Farha, R., Alefishat, E., Al Omar, S., Momani, D., Gharabli, A., . . . Rihani, R. (2017). Adherence to 6-mercaptopurine in children and adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. PLOS ONE, 12(9), e0183119. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183119

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2012). Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics, 129, 394–404. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3084

Barakat, L.P., Schwartz, L.A., Reilly, A., Deatrick, J.A., & Balis, F. (2014). A qualitative study of phase III cancer clinical trial enrollment decision-making: Perspectives from adolescents, young adults, caregivers, and providers. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 3, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2013.0011

Bhatia, S., Landier, W., Hageman, L., Chen, Y., Kim, H., Sun, C.L., . . . Relling, M.V. (2015). Systemic exposure to thiopurines and risk of relapse in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A Children’s Oncology Group study. JAMA Oncology, 1, 287–295. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0245

Bhatia, S., Landier, W., Hageman, L., Kim, H., Chen, Y., Crews, K.R., . . . Relling, M.V. (2014). 6MP adherence in a multiracial cohort of children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A Children’s Oncology Group study. Blood, 124, 2345–2353. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-01-552166

Bleyer, A., Ulrich, C., & Martin, S. (2012). Young adults, cancer, health insurance, socioeconomic status, and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Cancer, 118, 6018–6021. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.27685

Bluebond-Langner, M., Belasco, J.B., & DeMesquita Wander, M. (2010). “I want to live, until I don’t want to live anymore:” Involving children with life-threatening and life-shortening illnesses in decision making about care and treatment. Nursing Clinics of North America, 45, 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cnur.2010.03.004

Britto, M., Cote, M., Horning, R., & Slap, G. (2004). Do adolescents with chronic illness want to make decisions about their treatment. Journal of Adolescent Health, 34, 120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.11.079

Britto, M.T., Slap, G.B., DeVellis, R.F., Hornung, R.W., Atherton, H.D., Knopf, J.M., & DeFriese, G.H. (2007). Specialists understanding of the health care preferences of chronically ill adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 40, 334–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.020

Broome, M.E., & Richards, D.J. (2003). The influence of relationships on children’s and adolescents’ participation in research. Nursing Research, 52, 191–197.

Broome, M.E., Richards, D.J., & Hall, J.H. (2001). Children in research: The experience of ill children and adolescents. Journal of Family Nursing, 7, 32–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/107484070100700103

Butow, P., Palmer, S., Pai, A., Goodenough, B., Luckett, T., & King, M. (2010). Review of adherence-related issues in adolescents and young adults with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 4800–4809. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2009.22.2802

Coccia, P.F., Pappo, A.S., Altman, J., Bhatia, S., Borinstein, S.C., Flynn, J., . . . Sundar, H. (2014). Adolescent and young adult oncology, version 2.2014. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 12, 21–32.

Coyne, I. (2008). Children’s participation in consultations and decision-making at health service level: A review of the literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45, 1682–1689.

Coyne, I., Amory, A., Kiernan, G., & Gibson, F. (2014). Children’s participation in shared decision-making: Children, adolescents, parents and healthcare professionals’ perspectives and experiences. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18, 273–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2014.01.006

Coyne, I., & Gallagher, P. (2011). Participation in communication and decision-making: Children and young people’s experiences in a hospital setting. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20, 2334–2343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03582.x

Coyne, I., & Harder, M. (2011). Children’s participation in decision-making: Balancing protection with shared decision-making using a situational perspective. Journal of Child Health Care, 15, 312–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367493511406570

Day, E., Jones, L., Langner, R., & Bluebond-Langner, M. (2016). Current understanding of decision-making in adolescents with cancer: A narrative systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 30, 920–934. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216316648072

de Vries, M.C., Wit, J.M., Engberts, D.P., Kaspers, G.J., & van Leeuwen, E. (2010). Pediatric oncologists’ attitudes towards involving adolescents in decision-making concerning research participation. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 55, 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.22510

Dunsmore, J., & Quine, S. (1996). Information, support, and decision-making needs and preferences of adolescents with cancer: Implications for health professionals. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 13(4), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1300/J077V13N04_03

Ellis, R., & Leventhal, B. (1993). Information needs and decision-making preferences of children with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 2, 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.2960020407

Hinds, P.S., Drew, D., Oakes, L.L., Fouladi, M., Spunt, S.L., Church, C., & Furman, W.L. (2005). End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 23, 9146–9154. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2005.10.538

Jacobs, S., Perez, J., Cheng, Y.I., Sill, A., Wang, J., & Lyon, M.E. (2015). Adolescent end of life preferences and congruence with their parents’ preferences: Results of a survey of adolescents with cancer. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 62, 710–714. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25358

Joffe, S., Fernandez, C.V., Pentz, R.D., Ungar, D.R., Mathew, N.A., Turner, C.W., . . . Kodish, E. (2006). Involving children with cancer in decision-making about research participation. Journal of Pediatrics, 149, 862–868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.027

Kelly, K.P., Mowbray, C., Pyke-Grimm, K., & Hinds, P.S. (2017). Identifying a conceptual shift in child and adolescent-reported treatment decision making: “Having a say, as I need at this time.” Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 64. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.26262

Knopf, J.M., Hornung, R.W., Slap, G.B., DeVellis, R.F., & Britto, M.T. (2008). Views of treatment decision making from adolescents with chronic illnesses and their parents: A pilot study. Health Expectations, 11, 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00508.x

Lyon, M.E., McCabe, M.A., Patel, K.M., & D’Angelo, L.J. (2004). What do adolescents want? An exploratory study regarding end-of-life decision-making. Journal of Adolescent Health, 35, 529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.009

Martenson, E.K., & Fägerskiöld, A.M. (2008). A review of children’s decision-making competence in health care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 17, 3131–3141. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01920.x

Masera, G., Chesler, M.A., Jankovic, M., Ablin, A.R., Ben Arush, M.W., Breatnach, F., . . . Spinetta, J.J. (1997). SIOP Working Committee on psychosocial issues in pediatric oncology: Guidelines for communication of the diagnosis. Medical and Pediatric Oncology, 28, 382–385.

Miller, V.A. (2009). Parent-child collaborative decision making for the management of chronic illness: A qualitative analysis. Families, Systems and Health, 27, 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017308

Miller, V.A., Baker, J.N., Leek, A.C., Hizlan, S., Rheingold, S.R., Yamokoski, A.D., . . . Kodish, E. (2013). Adolescent perspectives on phase I cancer research. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 60, 873–878. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24326

Miller, V.A., & Harris, D. (2012). Measuring children’s decision-making involvement regarding chronic illness management. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 37, 292–306. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsr097

Miller, V.A., Reynolds, W.W., & Nelson, R.M. (2008). Parent-child roles in decision making about medical research. Ethics and Behavior, 18, 161–181.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D.G. (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 1006–1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

Noblit, G.W., & Hare, D.R. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A.C., Salsberg, J., Jagosh, J., & Seller, R. (2012). Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49, 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002

Pearce, S., Brownsdon, A., Fern, L., Gibson, F., Whelan, J., & Lavender, V. (2016). The perceptions of teenagers, young adults and professionals in the participation of bone cancer clinical trials. European Journal of Cancer Care. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12476

Pluye, P., Gagnon, M.P., Griffiths, F., & Johnson-Lafleur, J. (2009). A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46, 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.01.009

Read, K., Fernandez, C.V., Gao, J., Strahlendorf, C., Moghrabi, A., Pentz, R.D., . . . Kodish, E. (2009). Decision-making by adolescents and parents of children with cancer regarding health research participation. Pediatrics, 124, 959–965. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-2878

Ruhe, K.M., Badarau, D.O., Brazzola, P., Hengartner, H., Elger, B.S., & Wangmo, T. (2016). Participation in pediatric oncology: Views of child and adolescent patients. Psycho-Oncology, 25, 1036–1042. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4053

Ruhe, K.M., Wangmo, T., De Clercq, E., Badarau, D.O., Ansari, M., Kuhne, T., . . . Elger, B.S. (2016). Putting patient participation into practice in pediatrics—Results from a qualitative study in pediatric oncology. European Journal of Pediatrics, 175, 1147–1155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-016-2754-2

Smith, S.D., Rosen, D., Trueworthy, R.C., & Lowman, J.T. (1979). A reliable method for evaluating drug compliance in children with cancer. Cancer, 43, 169–173.

Snethen, J.A., Broome, M.E., Knafl, K., Deatrick, J.A., & Angst, D.B. (2006). Family patterns of decision-making in pediatric clinical trials. Research in Nursing and Health, 29, 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20130

Spinetta, J.J., Masera, G., Jankovic, M., Oppenheim, D., Martins, A.G., Ben Arush, M.W., . . . Eden, T. (2003). Valid informed consent and participative decision-making in children with cancer and their parents: A report of the SIOP Working Committee on psychosocial issues in pediatric oncology. Medical and Pediatric Oncology, 40, 244–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpo.10262

Stegenga, K., & Ward-Smith, P. (2008). The adolescent perspective on participation in treatment decision making: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 25, 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454208314515

Stewart, J.L., Pyke-Grimm, K.A., & Kelly, K.P. (2012). Making the right decision for my child with cancer: The parental imperative. Cancer Nursing, 35, 419–428.

Tenniglo, L.J.A., Loeffen, E.A.H., Kremer, L.C.M., Font-Gonzalez, A., Mulder, R.L., Postma, A., . . . Tissing, W.J.E. (2017). Patients’ and parents’ views regarding supportive care in childhood cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25, 3151–3160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3723-7

Unguru, Y. (2011). Making sense of adolescent decision-making: Challenge and reality. Adolescent Medicine, 22, 195–206.

Unguru, Y., Sill, A.M., & Kamani, N. (2010). The experiences of children enrolled in pediatric oncology research: Implications for assent. Pediatrics, 125, e876–e883. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3429

Weaver, M.S., Baker, J.N., Gattuso, J.S., Gibson, D.V., Sykes, A.D., & Hinds, P.S. (2015). Adolescents’ preferences for treatment decisional involvement during their cancer. Cancer, 121, 4416–4424. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29663

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52, 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Young, B., Dixon-Woods, M., Windridge, K.C., & Heney, D. (2003). Managing communication with young people who have a potentially life threatening chronic illness: Qualitative study of patients and parents. BMJ, 326, 305. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7384.305

Zwaanswijk, M., Tates, K., van Dulmen, S., Hoogerbrugge, P.M., Kamps, W.A., Beishuizen, A., & Bensing, J.M. (2011). Communicating with child patients in pediatric oncology consultations: A vignette study on child patients’, parents’, and survivors’ communication preferences. Psycho-Oncology, 20, 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1721

Zwaanswijk, M., Tates, K., van Dulmen, S., Hoogerbrugge, P.M., Kamps, W.A., & Bensing, J.M. (2007). Young patients’, parents’, and survivors’ communication preferences in paediatric oncology: Results of online focus groups. BMC Pediatrics, 7, 35.