Wearing the Mask of Wellness: The Experience of Young Women Living With Advanced Breast Cancer

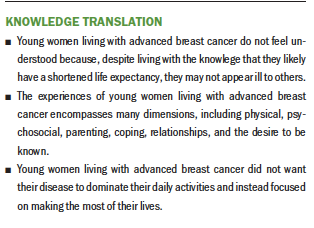

Purpose: To describe and interpret the lived experiences of young women with advanced breast cancer.

Participants & Setting: 12 women, aged 25–39 years with advanced breast cancer, were recruited from private Facebook groups for women with breast cancer.

Methodologic Approach: Van Manen’s hermeneutic phenomenologic method was used. Data were collected through one or more semi-structured interviews over a six-month period. Analysis was conducted using NVivo, version 11.

Findings: The participants’ multidimensional experiences were described by the overarching theme of wearing the mask of wellness in the presence of life-threatening illness.

Implications for Nursing: This study provides insight into the experiences of young women living with advanced breast cancer. Because these women may not appear ill to the general population, their needs and struggles are not well understood. The results of this study can be a baseline for additional research and clinical interventions.

Jump to a section

Young adult women with breast cancer often face a disease that is clinically more aggressive and has lower survival rates compared to those who are older (Korde et al., 2015; Partridge et al., 2014). When most young women are diagnosed, they are still developing their identities, finding their place in the world, establishing their careers, developing their relationships, and building their families (Chen, Parmar, & Gartshore, 2014; Cleeland et al., 2014; Shaha & Bauer-Wu, 2009). Limited research on the specific needs of this group of women exists, and even less literature studies the day-to-day experiences of young adult women living with an advanced-stage disease. This article describes a hermeneutic qualitative study of the meaning of living with advanced breast cancer for a cohort of young women. Findings are presented and implications for additional research and clinical interventions are discussed.

Background

Young women with advanced breast cancer are likely to experience vulnerabilities that differ from those experienced by older women, particularly in terms of the psychological and emotional burdens of living with an advanced disease. In addition, the physical and functional challenges that accompany this disease and its treatment can further exacerbate emotional burdens. Often, these young women are living with, and enduring, a disease that is likely to claim their lives prematurely and unexpectedly.

Breast cancer is one of the most common cancers in women younger than age 40 years (National Cancer Institute, 2018). Excluding accidental deaths, breast cancer is the leading cause of death for women aged 20–39 years, and studies indicate that additional research with this population is needed across all aspects of the cancer continuum (DeRouen et al., 2015; National Cancer Institute, 2018; Siegel, Miller, & Jemal, 2016). In addition, younger women often present with more advanced disease. For these women, the five-year survival is only 36% (Mariotto, Etzioni, Hurlbert, Penberthy, & Mayer, 2017). The frequency of advanced stage at presentation has also increased over the past 35 years in the United States (Johnson, Chien, & Bleyer, 2013).

At diagnosis, about 4%–6% of women already have metastatic disease (Cardoso et al., 2017; Krigel, Myers, Befort, Krebill, & Klemp, 2014; National Cancer Institute, n.d.), and about 30% of women with early-stage breast cancer will go on to develop metastatic breast cancer (O’Shaughnessy, 2005). For those with metastatic disease, treatment no longer focuses on curing the cancer but on providing palliative care, controlling symptoms, and improving quality of life (Harding et al., 2013; Krigel et al., 2014). Although advances in the treatment and management of metastatic breast cancer can extend lives and improve quality of life for some, it remains incurable for most (Harding et al., 2013). To date, no national database for tracking statistics related to this disease exists (Mariotto et al., 2017).

In addition, the uncertainty of a metastatic breast cancer diagnosis presents significant challenges for women and their families and affects their lives on a personal, familial, social, and economic level (Di Lascio & Pagani, 2017). Women with metastatic breast cancer and their families are also likely to experience challenges related to managing physical symptoms and may encounter psychosocial issues that can affect their quality of life (Mayer et al., 2010). Emerging research supports the belief that a significant number of women with metastatic disease feel ignored, invisible, voiceless, and misrepresented as women who have “lost the battle” against breast cancer (Danesh, Belkora, Volz, & Rugo, 2014; Mayer et al., 2010).

A survey of the literature revealed that the challenges and needs of young women living with advanced breast cancer are not well understood. Much of the research focusing on women with advanced breast cancer incorporates a wide range of ages and stages. Although women may have common and shared experiences of living with advanced breast cancer, these experiences can be specific to their age, life stage, and familial responsibilities. According to the limited research available, younger women with advanced breast cancer face unique challenges in their daily lives, while also sharing some of those suffered by older women (DeSanto-Madeya, Bauer-Wu, & Gross, 2007; Shaha & Bauer-Wu, 2009). Many women in this population continue to live and work, as well as to fulfill typical roles, responsibilities, and other commitments for extended periods of time following diagnosis. Although some women may remain independent for relatively long periods of time, others may experience accumulating symptom burden and deterioration of function rapidly. Additional studies described this population as feeling forgotten and alone, with persistently unrecognized and unmet needs, including physical, informational, psychosocial, and existential (Haylock, 2010a, 2010b; Lynn, 2005; Singer et al., 2015).

The purpose of this study was to describe and to interpret the lived experiences of young women with advanced breast cancer from their perspective, as well as to determine what shared experiences exist among this population.

Methods

This longitudinal, qualitative study, guided by van Manen’s (1984, 1990) hermeneutic phenomenologic approach, aimed to understand the meaning of the experience for young women living with advanced breast cancer. Van Manen’s approach facilitates the engagement of participants in a personal exploration of the meaning of a phenomenon in a way that allows hidden aspects of their experiences to emerge (Lopez & Willis, 2004; van Manen, 1984).

Participants and Setting

A purposive sample of women aged 25–39 years with advanced breast cancer (stages III and IV) was recruited for this study from private Facebook groups specifically for women with breast cancer. Inclusion criteria were: (a) women aged 25–39 years; (b) with a diagnosis of advanced breast cancer, stage III or IV; (c) able to effectively communicate in English; and (d) willing and able to provide informed consent to participate in the study. Participants receiving hospice care were excluded.

Procedures

Flyers recruiting participants were posted in two outpatient settings at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, MA, and UMASS Memorial Health Care in Worcester, MA, and on private Facebook pages that provide support for women with breast cancer. Enrollment continued until thematic saturation was achieved, and no new codes or themes appeared in the data (Creswell, 2014). Data collection took place over a six-month period. The intent was to conduct two interviews two to six weeks apart; however, not all participants were able to complete the second interview for various reasons, including worsening symptoms. Participants were also provided with journals where they could write additional thoughts that were stimulated by or arose from the first interview (van Manen, 1984, 1990). The first interview focused on exploring daily life experiences. The second interview drew on insights from the initial interview and focused primarily on additional elaborating on experiential or circumstantial changes related to living with advanced breast cancer. A third interview was conducted two to six months after the second encounter to validate findings with participants (member checking). During the third discussion, the developed themes were reviewed orally with participants on the telephone, or via Skype or FaceTime, to ensure congruence with their experience.

Interviews were digitally audio recorded, and professionally transcribed field notes, observations, and procedural and personal reflections were documented by the researcher. Field notes enhanced the transparency of analytic insight (Willis, Sullivan-Bolyai, Knalf, & Zichi-Cohen, 2016). In addition, the researcher met with advisors frequently to review developing themes for data inter-rater reliability.

Data Sources

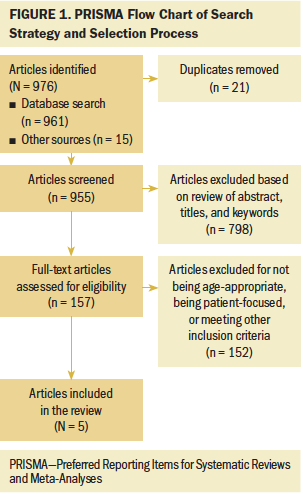

A demographic information form was completed by all participants and gathered the following data: age, date of diagnosis, previous treatment, date of metastatic disease diagnosis, current treatment, marital status, socioeconomic status, level of education, employment, faith tradition, and spiritual practices. All interviews took place via telephone, Skype, or FaceTime based on participant preference. Participants were asked various questions regarding their experience of living with advanced breast cancer, and probes were used, as needed, to gain more detail, clarifications, or examples (see Figure 1).

Data Analysis

The goal of hermeneutic analysis is to provide descriptions that capture and communicate the meaning of the lived experience from the participant’s perspective and to provide insights into commonalities among the experiences of all participants (van Manen, 1984, 1990). Data gathering and analysis were conducted concurrently in line with van Manen’s method, using new insights from the participants’ initial interview to inform subsequent interviews. In addition to manual coding, the researcher analyzed the data using NVivo, version 11, for Mac, a qualitative data software tool that permits organizing, categorizing, and accessing data, such as transcripts, journal entries, and field notes.

Findings

Sample Characteristics

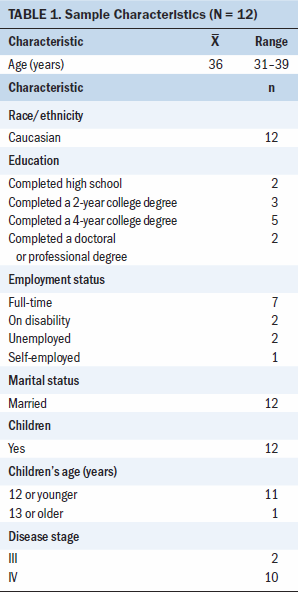

Sixteen women responded to the Facebook posts that advertised the study. Two were ineligible based on age, and two others did not reply to follow-up emails. Twelve women from 10 different states enrolled in the study. Additional demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Five participants were initially diagnosed with stage II breast cancer, and four were initially diagnosed as stage III. Of the twelve participants, three were diagnosed with de novo metastatic breast cancer, meaning that they already had metastatic disease at diagnosis. None of the women were receiving palliative care at the time of the study. Twelve women participated in the first interview, nine participated in a second interview that took place about two to six weeks later, and six participated in a third follow-up interview two to six months later to review the findings and established themes. Three participants wrote journal entries that they returned to the researcher at the conclusion of the interviews.

Overarching Theme

The overall meaning of the experience for the young women in this study was interpreted as wearing the mask of wellness in the presence of a life-threatening illness. The overarching theme was comprised of five major themes as described by the participants:

• Wanting to be known as the person I am

• I’m still Mom

• Living is more than surviving

• Getting through it

• Being connected to others

Each theme represented a different facet of the overall phenomenon of the experience of young women living with advanced breast cancer. Wearing the mask of wellness in the presence of a life-threatening illness was defined as the dichotomy of appearing young and healthy to others and continuing to carry out daily routines, including parenting and maintaining relationships, while being continually aware of living with a potentially terminal illness that could shorten time with one’s children and significant others. The desire to be known as a person apart from the disease, but also to be understood as living with this disease, was described by many participants.

That’s one of the things that people don’t understand about having stage IV cancer. I think a lot of people think [your] appearance should be bald and super thin and kind of sickly looking. When I tell people, “I’ll always have stage IV cancer,” they look at me. “No, you don’t.” I’m like, “I look normal. I know.” You can look normal. People don’t realize that. (Dina)

Wearing the mask of wellness in the presence of a life-threatening illness represents a multidimensional experience that captures different aspects of young women living with advanced breast cancer. Each dimension of the phenomenon is presented in one of the five themes.

Theme 1: Wanting to Be Known as the Person I Am

Wanting to be known as the person I am is the ambivalent and sometimes conflicting feeling of wanting to be known in all of one’s complexity, including as an individual and as someone who is living with a life-threatening illness. Perceiving others as making assumptions about one’s physical or psychological health, either as a person who looks well or who has a disease, can be isolating. Participants wanted not only to be known as a person with a disease but also as a person apart from the disease. Participants discussed looking “normal,” as opposed to when they were receiving curative treatments and experienced alopecia, weight loss, pallor, and fatigue. To the young women in this study, this discrepancy between perception and reality often caused others not to understand or to remember what they were struggling with on a daily basis. The majority of the participants alluded to this experience of no longer being “known” in the same way as they had been prior to their diagnosis of stage III or IV cancer. A mother of three explained:

Well, when people find out I have cancer, I’m told [that] I don’t look like I have cancer because I don’t look like I’m dying right this second, thankfully. Because it went to my bones, I got to keep my breasts. There’s no need to cut them off when [the cancer is] already out of them. After I finished four rounds of Taxotere®, [my] hair grew back in. So, I think it’s important that people get educated on the fact that just because I don’t look like I have cancer anymore, I still have cancer. It’s still important socially and for your mental health that people still . . . I don’t want to be treated like a cancer patient. (Amy)

Although some of the young women in this study often appeared healthy and “normal” to others because they did not have the expected physical appearance of a patient with cancer, their experiences were anything but normal. The participants reported that when they were fatigued or suffering from pain, they would have welcomed assistance, but they often were not be seen by others as being in need. However, these women did not want to be viewed solely as their disease. These women wore the mask of wellness to maintain their sense of self. An additional psychological issue identified by the young women was that they are living with the knowledge that it is likely that their lives will be shortened by the disease.

Theme 2: I’m Still Mom

I’m still Mom reflects the desire to continue parenting one’s children despite the difficulties and challenges faced as a result of stage III or IV disease. Participants expressed that the hardest part of being a young woman with advanced breast cancer was motherhood. Being a mother was the top priority for the women in this study; however, they were hindered in carrying out their role as a mother because of physical side effects and uncertainty about the future. They also wanted to find supportive resources, create good memories, and protect their children from the collateral damage of their illness. As one participant described:

I mean, literally, when you’re a cancer patient and you have your own kids, the cancer stuff is secondary. You still have to take care of your kids. So, in a way, it makes it a little bit easier, maybe psychologically, because you still have to live your normal life. But logistically, it’s a nightmare. (Laura)

These women wore the mask of wellness by continuing to assume care for their children and trying to normalize their lives while also preparing them for the future.

Theme 3: Living Is More Than Surviving

The experiences of daily life were captured by the theme of living is more than surviving. Daily life experiences reflect the multidimensional aspect of this theme, which is defined as trying to live as fully as possible within the constraints of the disease.

Many participants described how life went on and how they tried to keep their lives as normal as possible despite their diagnosis, as well as how they tried to continue enjoying life. The young women saw life as being more than surviving. Knowing that they needed to embrace their new normal, they chose to live purposely. For one young woman, this meant continuing to do everything that she did before her metastatic diagnosis:

I mean, I think the whole, “life goes on,” thing is a big part of it. If I knew I was going to die in two weeks, maybe I would have a different plan or perspective or routine, but I don’t plan on that. So, I just keep . . . I do as much as I can. I rest a little more if I have to, but staying busy and doing the normal things is what makes you—it gives you some normalcy and sense of control. Like, “Oh, I can still get up and go to work and act like a perfectly normal person, and just live [laughter].” Not just survive. (Laura)

This theme incorporated what daily life and its struggles are like for these young women as they strive for a sense of normalcy. Each was focused on living with their illness and, for some, living their normal life despite the disease. In addition, this theme illustrated another aspect of wearing the mask of wellness: working, volunteering, caring for children and families, and engaging in life in many of the ways that they did prior to diagnosis. By keeping busy and focused on maintaining their normal lifestyle, aspects of living with advanced breast cancer remained hidden from others.

Theme 4: Getting Through It

The theme of getting through it focused on the elements of coping with advanced breast cancer, including emotional and behavioral components. Maintaining a sense of control and maximizing experiences were important aspects of this theme. For those young women who had initially been diagnosed with early-stage disease and had hoped for cure, the diagnosis of metastatic disease was unexpected and incredibly difficult. Being aware that the intent of treatment for metastatic cancer was no longer curative was shocking for some participants. One participant explained:

It was overwhelming. And then I got really—I wouldn’t say angry—frustrated. Because it’s like, those are the things that you did because there is a chance that you’re going to get better. But I’m not going to get better. (Mary)

This theme provided a deeper understanding of the complexities of coping and comprised a multitude of emotions and behaviors. For most young women, their feelings were motivated by concerns for their children and the desire to extend their lives as much as possible. For one young woman, “getting through it” was not a choice.

Wanting to make sure [that] I’m doing everything right, and the extra pressure of having to make sure I’m here for the kids, is also—it’s a very heavy responsibility. It’s doing everything I can. I don’t have a choice. I can’t give up. I can’t stop and that’s a good thing. It is definitely a good thing that they’re here to push me because I would have given up already. (Amy)

Theme 5: Being Connected to Others

Being connected to others reflected the need for and challenges regarding relationships with others while living with advanced breast cancer. Most participants expressed feelings of isolation in their relationships, which were the result of not knowing anyone else with a similar experience of being a young woman with children and having cancer. Being connected to others is defined as the experience of being in relationships with others, the desire for new relationships, and changes in relationships that may occur for young women living with advanced breast cancer.

For one participant, knowing that no matter what happened to her, her children would be supported and cared for helped to lessen her worries and provided reassurance.

I have such a good family [and] such a good support system that I know that if something does happen, my kids are going to be taken care of. I don’t have to worry, “Okay, is someone going to teach them this? Is someone going to teach them that?” Because I know that there are people that are going to do that. And so, I mean, that really helps out. (Amy)

Discussion

The overarching theme analyzed from these findings, wearing the mask of wellness in the presence of a life-threatening illness, captured the experiences of all the women in this study. The theme provided new insight about the experiences of being a young women with advanced breast cancer that was not present in the literature and, according to the accounts of this study’s participants, is not well understood by clinicians. This description of the meaning of the overall phenomenon adds to the baseline knowledge of what life is like for these women on a daily basis. This study revealed a previously poorly understood dichotomy between how young women with advanced breast cancer are perceived and how they actually feel. These women desire to feel understood and known as individuals who are living with a life-threatening illness; however, they do not want to be forced into the patient role. The experiences of these women have important implications for healthcare providers in terms of developing appropriate interventions, approaches, and interactions for their patients. This was particularly apparent in those who had been initially diagnosed with an early-stage breast cancer and had undergone treatment with curative intentions. The women undergoing curative treatments “looked” like someone with cancer compared to their experience of having metastatic disease where they appeared healthy.

The mask of wellness is similar to the “mask of aging” metaphor, in which older adults experience a disconnection between how they feel and how they appear. Rozario and Derienzis (2009) conducted a qualitative study that examined the mask of aging in older adults. According to the results of their study, older adults continued to see themselves as not old even in the face of advanced age and comorbid conditions. In this study of young women, an opposing disconnection was revealed. The young women appeared young and healthy; however, internally, they carried the knowledge and experiences of an advanced breast cancer diagnosis.

In addition, the theme of wanting to be known as the person I am was consistent with the earlier work of Knox et al. (2017), who used a hermeneutic approach to understand the experience of living with advanced cancer. Their sample consisted of 10 young adult men and women with different advanced cancers. Themes included feeling lost and stranded, as well as themes of being isolated and having developmental and existential concerns. The themes established by Knox et al. (2017) echo the themes developed by this study. The sense of isolation described by the young women in this study included the feeling that others did not understand them or their circumstances. Their circumstances differed from those who may have been older and also living with advanced cancer. Most of the women in this study did not know other individuals in their situation who were managing households, small children, work responsibilities, and existential concerns related to their likely shortened life span.

Although the findings of Knox et al. (2017) provide some insight into the experiences of living with advanced cancer, the heterogeneous nature of the sample makes it difficult to extrapolate to specific populations without additional research. This study supports Knox et al.’s findings by extending and refining the experiences related to a specific group of young women living with advanced breast cancer.

Existential, physical, and psychosocial needs have been the foci of most prior research. Previous studies have addressed aspects of living with advanced cancer and support identifying the ways that some are living with an advanced cancer diagnosis to provide better care for patients (Chen et al., 2014; Cleeland et al., 2014; DeSanto-Madeya et al., 2007; Novartis Oncology, 2014). However, none of these studies focused exclusively on the experiences of young women with advanced breast cancer within the context of their daily lives.

The descriptions and experiences of wearing the mask of wellness and living with the knowledge that the future and life expectancy are uncertain is a significant finding and one that merits additional research. The findings of this study augment the existing body of knowledge and add new insights into the personal perspectives of daily living for young women with advanced breast cancer.

Limitations

As with other qualitative studies, the findings of this study are limited because they are not readily generalizable to larger populations. This was a homogeneous sample, with the majority of participants being well educated and Caucasian, and the experiences described by these participants may not reflect the experiences of women of color or women who are less educated. Because the flyer for recruitment was only accessible on social media, participants were required to use a computer or cell phone with Internet access.

In addition, the time frame for interviews and follow-up presented limitations. Because of disease- and treatment-related concerns, as well as the demands of daily life, scheduling the second interview two to six weeks after the first interview was not realistic for all participants. Similarly, the short interval between the first two interviews limited the ability for participants to perceive changes in their experiences as they occurred over time. An extended timeline may have provided better self-reflection and understanding.

Implications for Nursing

Insights about the experience of young women living with advanced breast cancer can enhance knowledge in nursing practice. The findings from this study provide strategies for clinical and advanced practice nurses that can be implemented easily. Young women who are known to be living with advanced breast cancer can be asked about their daily lives, their sense of isolation, their support system, and their coping strategies, and nurses can assist in obtaining resources for these patients as needed. In addition, assessment of quality of life, discussions about the initiation of palliative care, and advanced care planning emerged from this study as areas that need to be incorporated in the care of this population to promote positive decision making and self-efficacy. In addition, although the interviews were not focused on the young women’s experiences with healthcare providers, many participants identified areas of patient care that could be improved. These areas included the desire for a more humanizing experience, improved opportunities for supporting the patients and their families, and improved access to resources for more information and assistance with coping.

Implications for Research

The descriptions and experiences of the participants that helped conceptualize the theme of wearing the mask of wellness in the presence of a life-threatening illness illuminated several areas for additional research. For example, conducting a survey developed from the insights of this study could determine whether experiences are similar among diverse groups. Initial work has been completed; however, additional research is needed to understand the experiences of young women living with advanced breast cancer more fully, as well as how their experiences may differ from, or are similar to, that of older adult women living with advanced cancer. Efforts to better understand the multidimensional coping process for this population is needed to develop effective person-centered supportive care interventions. In addition, better understanding of the experience of young adults who are living with advanced cancer and engaging in activities in their communities is important for developing outreach and education strategies.

Conclusion

This study contributes insights into the lived experiences of young women with advanced breast cancer. Although participants were aware of the life-threatening and potentially life-shortening nature of their cancer, they did not allow this to dominate their daily activities. Instead, participants focused on living with their illness, making the most of their lives and, for some, remaining engaged and active despite their disease. The findings from this study indicate that young women with advanced breast cancer manage multiple roles and responsibilities despite the ongoing challenges that they face because of treatment and symptom management. Wearing the mask of wellness exemplifies a young woman’s experience when outward appearances and social expectations hide the tremendous challenges in her life. Young women with advanced breast cancer believe that their needs and struggles are not well understood because to outsiders they do not look ill, so clinical interventions should focus on providing additional psychosocial support to the women in this population. This descriptive study provides a base for additional research on the experiences of this population.

About the Author(s)

Debra M. Lundquist, PhD, RN, is a clinical research nurse at Massachusetts General Hospital, and Donna L. Berry, PhD, RN, AOCN®, FAAN, is a nurse scientist in the Phyllis F. Cantor Center for Research in Nursing and Patient Care Services at Dana Farber Cancer Institute, both in Boston; Marie Boltz, PhD, GNP-BC, FAAN, is a professor in the College of Nursing at Penn State University in State College, PA; and Susan A. DeSanto-Madeya, PhD, MSN, RN, is an associate clinical professor, and Pamela J. Grace, RN, PhD, FAAN, is an associate professor, both in the William F. Connell School of Nursing at Boston College in Chestnut Hill, MA. Berry has previously received support from Amgen and Medocity. Mention of specific products and opinions related to those products do not indicate or imply endorsement by the Oncology Nursing Society. Lundquist completed the data collection and provided statistical support. All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design, provided the analysis, and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Lundquist can be reached at debra.lundquist@bc.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted August 2018. Accepted November 28, 2018.)

References

Cardoso, F., Costa, A., Senkus, E., Aapro, F., André, F., Barrios, C.H., . . . Winer, E. (2017). 3rd ESO-ESMO international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 3) (2017). Breast, 31, 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2016.10.001

Chen, B.Q., Parmar, M.P., & Gartshore, K. (2014). Supporting women with advanced breast cancer: The impact of altered functional status on their social roles. Canadian Oncology Nursing Journal, 24, 194–203.

Cleeland, C.S., Mayer, M., Dreyer, N.A., Yim, Y.M., Yu, E., Su, Z., . . . Kaufman, P.A. (2014). Impact of symptom burden on work-related abilities in patients with locally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer: Results from a substudy of the VIRGO observational cohort study. Breast, 23, 763–769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2014.08.004

Creswell, J.W. (2014). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

Danesh, M., Belkora, J., Volz, S., & Rugo, H.S. (2014). Informational needs of patients with metastatic breast cancer: What questions do they ask, and are physicians answering them? Journal of Cancer Education, 29, 175–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0566-x

DeRouen, M.C., Smith, A.W., Tao, L., Bellizzi, K.M., Lynch, C.F., Parsons, H.M., . . . Keegan, T.H. (2015). Cancer-related information needs and cancer’s impact on control over life influence health-related quality of life among adolescents and young adults with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 24, 1104–1115. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3730

DeSanto-Madeya, S., Bauer-Wu, S., & Gross, A. (2007). Activities of daily living in women with advanced breast cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 34, 841–846. https://doi.org/10.1188/07.ONF.841-846

Di Lascio, S., & Pagani, O. (2017). Is it time to address survivorship in advanced breast cancer? A review article. Breast, 31, 167–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2016.10.022

Harding, V., Afshar, M., Krell, J., Ramaswami, R., Twelves, C.J., & Stebbing, J. (2013). ‘Being there’ for women with metastatic breast cancer: A pan-European patient survey. British Journal of Cancer, 109, 1543–1548. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2013.492

Haylock, P.J. (2010a). Advanced cancer: A mind-body-spirit approach to life and living. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 26, 183–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2010.05.005

Haylock, P.J. (2010b). Advanced cancer: Emergence of a new survivor population. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 26, 144–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2010.05.008

Johnson, R.H., Chien, F.L., & Bleyer, A. (2013). Incidence of breast cancer with distant involvement among women in the United States, 1976 to 2009. JAMA, 309, 800–805. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.776

Knox, M.K., Hales, S., Nissim, R., Jung, J., Lo, C., Zimmermann, C., & Rodin, G. (2017). Lost and stranded: The experience of younger adults with advanced cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25, 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3415-8

Korde, L.A., Partridge, A.H., Esser, M., Lewis, S., Simha, J., & Johnson, R.H. (2015). Breast cancer in young women: Research priorities. A report of the young survival coalition research think tank meeting. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 4, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2014.0049

Krigel, S., Myers, J., Befort, C., Krebill, H., & Klemp, J. (2014). ‘Cancer changes everything!’ Exploring the lived experiences of women with metastatic breast cancer. International Journal of Palliative Nursing, 20, 334–342. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2014.20.7.334

Lopez, K.A., & Willis, D.G. (2004). Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qualitative Health Research, 14, 726–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304263638

Lynn, J. (2005). Living long in fragile health: The new demographics shape end of life care. Hastings Center Report, 35(6 Suppl.), S14–S18. https://doi.org/10.1353/hcr.2005.0096

Mariotto, A.B., Etzioni, R., Hurlbert, M., Penberthy, L., & Mayer, M. (2017). Estimation of the number of women living with metastatic breast cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Prevention, 26, 809–815. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0889

Mayer, M., Huñis, A., Oratz, R., Glennon, C., Spicer, P., Caplan, E., & Fallowfield, L. (2010). Living with metastatic breast cancer: A global patient survey. Community Oncology, 7, 406–412.

National Cancer Institute. (n.d.). Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Retrieved from https://seer.cancer.gov

National Cancer Institute. (2018). Choices for care when treatment may not be an option. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/advanced-cancer/care-choices

Novartis Oncology. (2014). The invisible woman: Unveiling the impact of advanced breast cancer on women, families, society and the economy across Europe. Retrieved from http://www.wearehereandnow.com/files/here-and-now-report.pdf

O’Shaughnessy, J. (2005). Extending survival with chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer. Oncologist, 10(Suppl. 3), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.10-90003-20

Partridge, A.H., Pagani, O., Abulkhair, O., Aebi, S., Amant, F., Azim, H.A., . . . Cardoso, F. (2014). First international consensus guidelines for breast cancer in young women (BCY1). Breast, 23, 209–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2014.03.011

Rozario, P.A., & Derienzis, D. (2009). ‘So forget how old I am!’ Examining age identities in the face of chronic conditions. Sociology of Health and Illness, 31, 540–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01149.x

Shaha, M., & Bauer-Wu, S. (2009). Early adulthood uprooted: Transitoriness in young women with breast cancer. Cancer Nursing, 32, 246–255. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e31819b5b2e

Siegel, R.L., Miller, K.D., & Jemal, A. (2016). Cancer statistics, 2016. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 66, 7–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21332

Singer, A.E., Meeker, D., Teno, J.M., Lynn, J., Lunney, J.R., & Lorenz, K.A. (2015). Symptom trends in the last year of life from 1998 to 2010: A cohort study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 162, 175–183. https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-1609

van Manen, M. (1984). “Doing” phenomenological research and writing: An introduction (Curriculum Praxis Monograph Series, Monograph No. 7). Edmonton, AL: University of Alberta.

van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Willis, D.G., Sullivan-Bolyai, S., Knafl, K., & Zichi-Cohen, M.Z. (2016). Distinguishing features and similarities between descriptive phenomenological and qualitative description research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 38, 1185–1204. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945916645499