Health Literacy in Adult Oncology: An Integrative Review

Problem Identification: Patients with cancer face high expectations for performing health literacy activities necessary for self-management and decision making, but only 12% of adults in the United States are proficient in health literacy. This review explores evidence regarding what is known about functional, interactive, and critical health literacy in adult oncology populations.

Literature Search: The review was conducted by searching extensively in the CINAHL® Plus database.

Data Evaluation: Of 614 articles retrieved from the literature search, 22 were included in the final sample. Most were cross-sectional, descriptive, correlational studies.

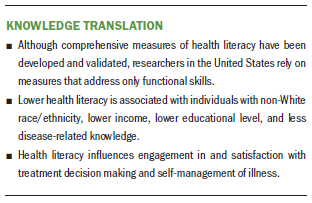

Synthesis: Health literacy research in the United States focuses primarily on functional health literacy, but studies that include interactive and/or critical health literacy indicate their applicability in adult oncology populations.

Implications for Research: Additional research is needed to clarify the role of health literacy in cancer care to develop effective interventions that facilitate self-management and decision making.

Jump to a section

Health literacy is frequently defined as a variation of the definition endorsed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, which is “the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions” (Nielsen-Bohlman, Panzer, & Kindig, 2004, p. 4). There are a growing number of broadened conceptualizations of health literacy attempting to capture its multidimensional and dynamic nature (Nutbeam, 2008; Pleasant, 2014; Rudd, 2015; Sørensen et al., 2012). One of the most widely studied health literacy frameworks, originally published by Nutbeam in 2000, has been applied across a variety of disciplines and health contexts. Nutbeam (2000, 2008) outlines three hierarchical dimensions of health literacy: functional, interactive, and critical.

Functional health literacy refers to foundational skills that are required for basic healthcare tasks, such as reading written instructions and completing health-related forms. This level of health literacy emphasizes conventional methods of patient education for the purposes of increasing knowledge and fostering compliance. Nutbeam (2000, 2008) defines the second level of health literacy as interactive (or communicative), referring to higher cognitive and social skills for participating in health communication and applying information to dynamic situations. Interactive health literacy skills contribute to motivation and confidence with which individuals are able to understand and act on information received through communication. The third and final level of health literacy is critical health literacy, or advanced cognitive and social skills necessary for critically analyzing and applying health information as a means to gain control over one’s health. With this model, proficient health literacy moves beyond reading and writing skills by also addressing the capacity to successfully access and apply health information toward an end result of individual empowerment (Nutbeam, 2000, 2008).

In the complex healthcare system in the United States, health literacy demands attention as focus shifts toward patient-centered care and self-management of health conditions. Although there are notable benefits to patient-centered care, it is critical to recognize the health literacy implications of such an approach (Office of Disease Prevention and Health [ODPH], 2010). Assuming a central role in health care requires a patient to engage in a number of health literacy skills, such as reading, writing, numeracy, communication, decision making, and navigation of the healthcare system (Helitzer, Hollis, Sanders, & Roybal, 2012). This becomes particularly important in the context of a cancer diagnosis, where patients are faced with numerous decisions about a life-threatening disease, often involving multiple treatment options with complicated regimens (Koay, Schofield, & Jefford, 2012). At the same time, advances in technology and medicine have lengthened survival for several types of cancer, allowing many patients to live with cancer as a chronic illness rather than a terminal disease (Husson, Mols, Fransen, van de Poll-Franse, & Ezendam, 2014). The interplay of these phenomena result in high expectations for the health literacy of patients with cancer. However, the most recent national assessment revealed that only 12% of the U.S. adult population meets the criteria for proficient health literacy, indicated by skills in reading and analyzing lengthy, complex information, as well as solving multistep mathematical problems (Kutner, Greenberg, Jin, & Paulsen, 2006). Considering that nearly 39% of the U.S. population will develop cancer in their lifetime, there is an urgency to develop knowledge regarding the role of health literacy in cancer care (National Cancer Institute [NCI], 2018).

Although health literacy has been widely studied across diverse patient populations and health conditions, there is a relatively small body of evidence specific to health literacy in patients living with cancer. The purpose of this integrative review is to analyze the current state of the science concerning how health literacy has been addressed in adult oncology populations, specifically examining definitions of health literacy, instruments used to measure health literacy, health outcomes related to health literacy, and how each of Nutbeam’s (2000, 2008) dimensions of health literacy have been addressed in this population.

Methods

This integrative literature review was conducted using the methodology proposed by Whittemore and Knafl (2005), consisting of five stages: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and presentation of findings. The CINAHL® Plus electronic database was searched for peer-reviewed articles published in English in the United States using the key terms health literacy and oncology, and health literacy and cancer. No time frame was specified to obtain a comprehensive picture of how health literacy has been researched in adult oncology over time. Of note, Nutbeam’s (2000, 2008) levels of health literacy were not used as a basis for data collection, but rather as a framework for evaluating which variables related to health literacy have been addressed.

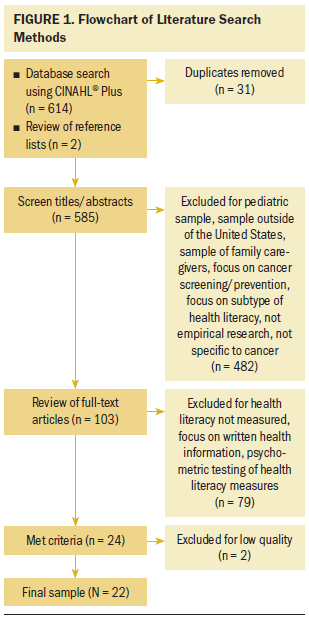

Only original research studies involving adults diagnosed with cancer in the United States were included in this integrative review. Direct measurement of health literacy was required. Articles were excluded if the focus was solely on written health information and/or a specific subtype of health literacy, such as mental health literacy, oral (dental) health literacy, or e-health literacy. The initial search retrieved 614 articles, with two additional articles identified from reference lists. After removing duplicates and application of inclusion/exclusion criteria, 24 articles remained. The remaining 24 studies were appraised for quality. Each study was assigned a score of A (high quality), B (good quality), or C (low quality) using criteria published by Johns Hopkins Medicine that considers research design, generalizability, sample size, control, and consistency with existing evidence (Dearholt & Dang, 2012). Two studies received a quality score of C and were eliminated, yielding a final sample of 22 studies (see Figure 1).

Data were analyzed in several phases. First, the articles were organized into an evidence table, detailing the following elements: authors and year of publication, quality score, purpose, design, sample characteristics, definition of health literacy, health literacy measure, and relevant findings. Studies were initially grouped based on how the authors conceptualized health literacy; throughout the analysis process, the studies were reorganized in various ways to compare specific elements relevant to the purposes of this review. Finally, data were extracted and collated according to the components of Nutbeam’s (2000, 2008) framework. Patterns within each of these categories were identified, along with gaps requiring further research.

Results

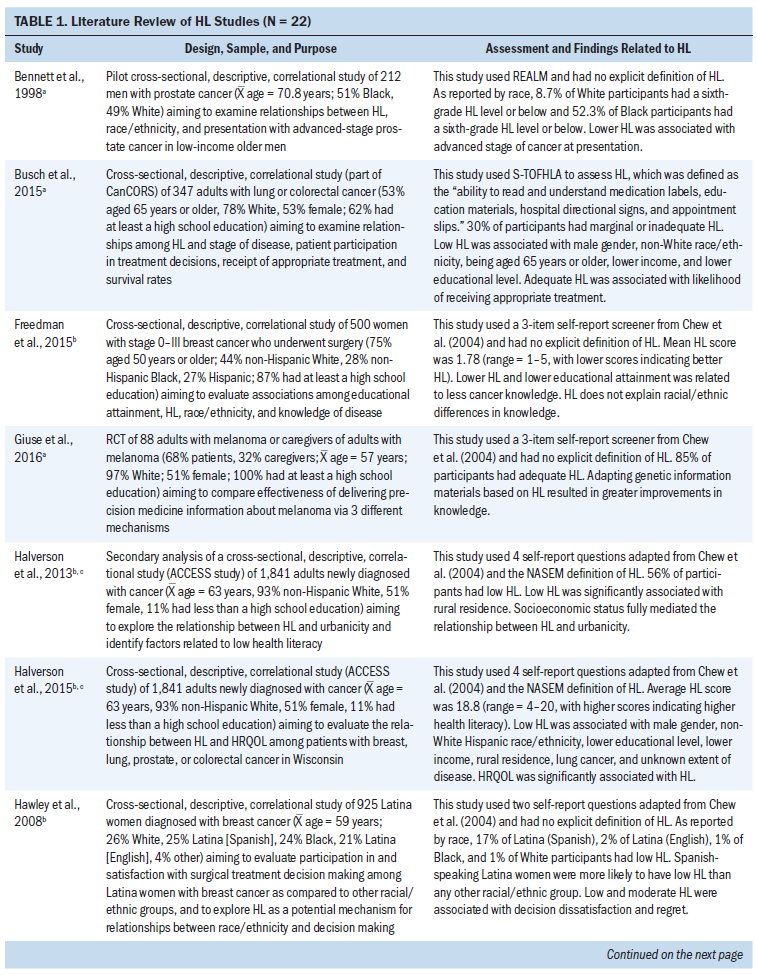

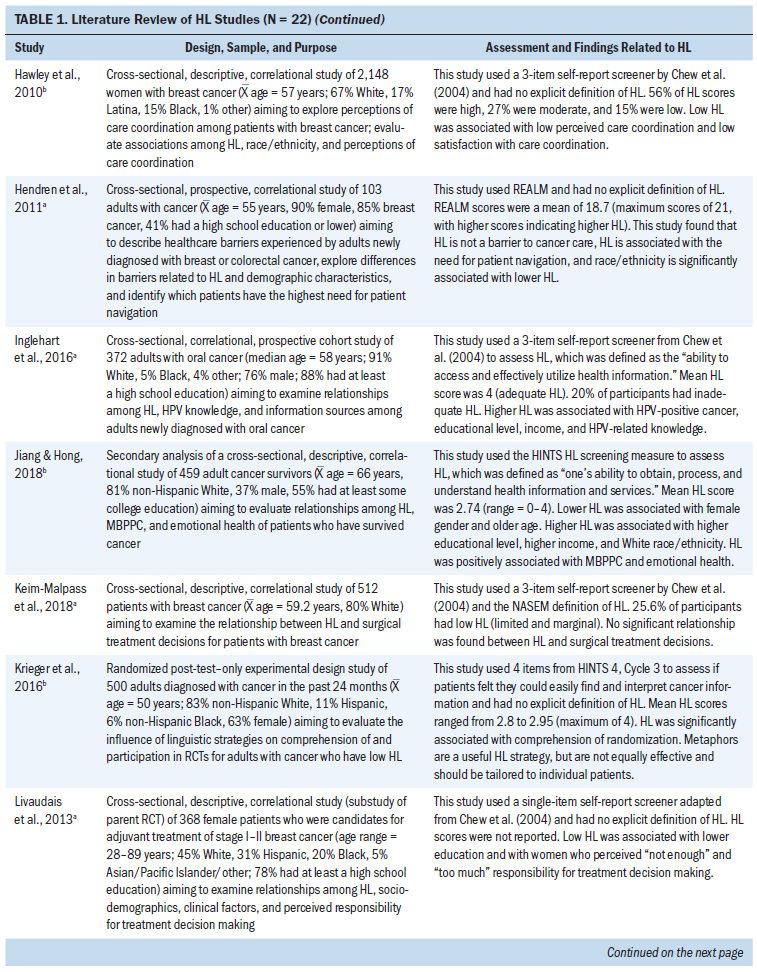

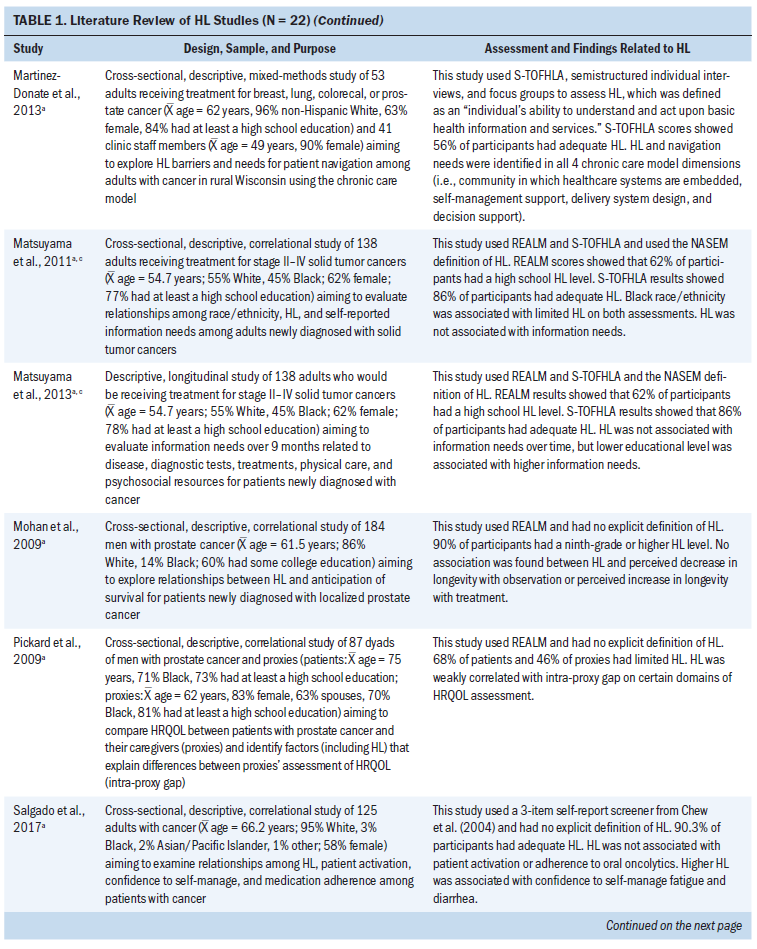

Because direct measurement of health literacy was an inclusion criterion, all of the reviewed articles were reports of empirical research. Although there were no qualitative studies, two used mixed methods for data collection and analysis (Hendren et al., 2011; Martinez-Donate et al., 2013). The majority of studies included in this review employ nonexperimental designs. Most of these (n = 17) were cross-sectional, descriptive studies, three of which described secondary analyses of previously collected data (Halverson et al., 2013, 2015; Jiang & Hong, 2018). In addition, there was one study with a longitudinal design (Matsuyama, Kuhn, Molisani, & Wilson-Genderson, 2013) and two prospective cohort studies (Hendren et al., 2011; Inglehart et al., 2016). Two employed experimental designs, including a randomized post-test–only study (Krieger, Neil, Strekalova, & Sarge, 2017) and a randomized controlled trial (Giuse et al., 2016). Of note, several of the studies reported various analyses on the same datasets. For the purposes of integrative synthesis in this review, these will be discussed as single studies in terms of definitions and measurement of health literacy and as separate studies in terms of reported findings.

Sample Characteristics

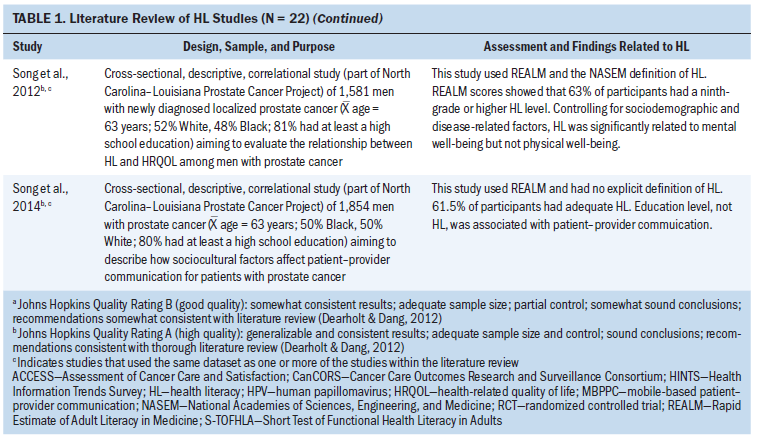

Table 1 summarizes characteristics and results of the 22 reviewed studies, which were published from 1998 to 2018. Various subpopulations of adults with cancer were represented within the studies, with the two most common being women with breast cancer (Freedman, Kouri, West, & Keating, 2015; Hawley et al., 2008, 2010; Keim-Malpass, Doede, Camacho, Kennedy, & Showalter, 2018; Livaudais, Franco, Fei, & Bickell, 2013) and men with prostate cancer (Bennett et al., 1998; Mohan et al., 2009; Pickard et al., 2009; Song et al., 2012, 2014). One study examined patients with oral cancer (Inglehart et al., 2016), and another examined patients with melanoma (Giuse et al., 2016). The remaining 10 studies recruited patients with diverse cancer diagnoses (Busch, Martin, DeWalt, & Sandler, 2015; Halverson et al., 2013, 2015; Hendren et al., 2011; Jiang & Hong, 2018; Krieger et al., 2016; Martinez-Donate et al., 2013; Matsuyama et al., 2011, 2013; Salgado et al., 2017). Two studies included patients and caregivers in the sample population (Giuse et al., 2016; Pickard et al., 2009).

In seven of the nine studies that included male and female participants, the percentage of female participants ranged from 51% to 63%. In one study that recruited participants with either breast or colorectal cancer, 85% of the sample had breast cancer; as a result, 90% of the participants were female (Hendren et al., 2011). In addition, in the study examining patients with oral cancer, only 24% of the participants were women, likely because the incidence of oral cancer in men is more than twice as high as in women (Inglehart et al., 2016; NCI, 2019). Across all 22 studies, the mean age of participants ranged from 49 to 75 years.

Half of the studies intentionally recruited diverse samples for the purpose of exploring racial/ethnic differences in research outcomes, including health literacy levels (Bennett et al., 1998; Freedman et al., 2015; Song et al., 2012, 2014), treatment decision making (Hawley et al., 2008; Livaudais et al., 2013), health-related quality of life (Pickard et al., 2009; Song et al., 2012), perceptions of care coordination (Hawley et al., 2010), barriers to health care (Hendren et al., 2011), information needs (Matsuyama et al., 2011, 2013), disease-related knowledge (Freedman et al., 2015), and patient–provider communication (Song et al., 2014). In 10 of these 11 studies, samples included an average of 47% White (n = 10, range = 26%–67%), 40% Black (n = 10, range = 15%–71%), 30% Hispanic/Latinx (n = 4, range = 17%–46%), and 3% other (n = 4, range = 1%–5%). Of note, one study’s sample was described as 61% White and 30% minority without specific delineation of other races/ethnicities (Hendren et al., 2011).

In the other 11 studies, the majority of participants were White (mean = 88%, range = 78%–97%). Six of these studies only reported sample percentages for White, with other races/ethnicities combined into categories labeled “other” or “non-White.” Four studies included sample percentages for Black (mean = 7%, range = 4%–14%), one reported 11% Latinx, and one reported 2% Asian/Pacific Islander.

Conceptualization of Health Literacy

None of the reviewed studies included all three dimensions of health literacy as conceptualized by Nutbeam (2000, 2008). Half (n = 11) focused only on functional health literacy in definition, measurement, and outcome variables. Three articles addressed the interactive dimension by exploring associations between health literacy and communication or social processes. The remaining eight studies incorporated critical health literacy, either in measurement (n = 2) or in associated outcomes, such as self-management (n = 1) and treatment decision making (n = 5).

Definitions of Health Literacy

The majority of reviewed articles referred to a functional definition of health literacy, emphasizing the ability to read and comprehend health-related information. Although many authors (n = 13) did not explicitly define health literacy, several (n = 6) cited the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine definition or an adapted version of it (n = 3). None used more comprehensive definitions, such as in Nutbeam’s (2000, 2008) conceptualization.

Measures of Health Literacy

There were four different methods of measuring health literacy represented in the reviewed articles, all of which focus primarily on functional literacy skills. Self-report was the most common measurement method, and the majority of articles found mean scores in the range of adequate health literacy, with 76%–90% of participants classified as moderate or high. The most commonly used instrument, used in five studies, involves three self-report screening questions addressing confidence in completing medical forms and difficulty reading or understanding hospital materials and is termed the brief screener (Chew, Bradley, & Boyko, 2004). The brief screener has also been validated as a single-item tool using only the question about completing medical forms, which was used in one study (Livaudais et al., 2013). Two studies used other adaptations of the brief screener, one of which tailored two of the questions to information about breast cancer (Hawley et al., 2008). Halverson et al. (2013) added a question to address critical health literacy skills needed to apply health information to one’s own situation. In their findings, 56% of participants had low health literacy; of note, the mean score was 18.8 (range = 4–20), and low health literacy was categorized as any score less than 20 of 20 (Halverson et al., 2013). A self-report approach was also used by two studies that examined questions from the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) 4, Cycle 3, which addressed the ability to find and interpret health-related information (Jiang & Hong, 2018; Krieger et al., 2016).

Six studies measured functional literacy skills using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM), which evaluates the ability to recognize and pronounce 66 medical terms. In studies using the REALM in which the majority of participants were White, mean scores were at least 60 of 66, indicating literacy at or above a ninth-grade level (Hendren et al., 2011; Mohan et al., 2009). Studies with racially or ethnically diverse samples tended to score lower on the REALM; two studies reported that 62%–63% of participants scored at the ninth-grade level (Matsuyama et al., 2011; Song et al., 2014), and two others found inadequate literacy levels in 68%–69% of participants (Bennett et al., 1998; Pickard et al., 2009). The Short Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (S-TOFHLA), which measures reading comprehension and basic mathematical skills (numeracy), was used in three studies (Busch et al., 2015; Martinez-Donate et al., 2013; Matsuyama et al., 2011, 2013). Studies using the S-TOFHLA found that most participants exhibited adequate health literacy, with rates ranging from 70% to 86%. Although one study reported that only 56% of health literacy scores were adequate, its findings indicated that the other 44% did not complete the S-TOFHLA assessment (Martinez-Donate et al., 2013).

Demographic Factors Related to Health Literacy

Seven studies concluded that non-White participants were significantly more likely to have lower health literacy (Busch et al., 2015; Halverson et al., 2015; Jiang & Hong, 2018), specifically Black participants (Bennett et al., 1998; Hendren et al., 2011; Matsuyama et al., 2011) and non-White Hispanic participants (Hawley et al., 2008). Lower health literacy was also positively associated with lower educational attainment (Busch et al., 2015; Halverson et al., 2015; Inglehart et al., 2016; Jiang & Hong, 2018; Livaudais et al., 2013), lower income (Busch et al., 2015; Halverson et al., 2015; Inglehart et al., 2016; Jiang & Hong, 2018), and older age (Busch et al., 2015; Jiang & Hong, 2018). Two studies found that men were more likely to have lower health literacy (Busch et al., 2015; Halverson et al., 2015), and one found that lower health literacy was more common in women (Jiang & Hong, 2018). In addition, one study reported that participants living in rural areas had 33% higher odds of having low health literacy than their urban or mixed-residence counterparts (Halverson et al., 2013). Socioeconomic status was found to be a mediator between health literacy and urbanicity (Halverson et al., 2015).

Factors Associated With Functional Health Literacy

Functional health literacy was the most commonly addressed level of health literacy among the reviewed studies, particularly in terms of health literacy measurement. In fact, all 22 studies used instruments that measured functional health literacy. Lower functional health literacy was found to be associated with poorer mental well-being and emotional health in cancer survivors in general (Jiang & Hong, 2018) and specifically in men with prostate cancer (Song et al., 2012). Low health literacy was also related to less knowledge about one’s own breast cancer (Freedman et al., 2015), knowledge about human papilloma-virus in the context of oral cancer (Inglehart et al., 2016), and understanding of randomization procedures for randomized controlled trials (Krieger et al., 2016). Participants with low health literacy tended to be diagnosed with prostate cancer at a later stage (Bennett et al., 1998) and were less satisfied with care coordination for breast cancer (Hawley et al., 2010). Health literacy was not significantly related to information needs (Matsuyama et al., 2011, 2013), physical well-being (Song et al., 2012), or perceived differences in longevity based on treatment options (Mohan et al., 2009).

Factors Associated With Interactive Health Literacy

Although no studies directly measured interactive health literacy, three studies explored interactive health literacy in adults with cancer by addressing patient–provider communication as a research outcome, producing varying results. Song et al. (2014) found that participants’ functional health literacy levels did not affect patient–provider communication for men with prostate cancer. Jiang and Hong (2018) reported that functional health literacy was significantly associated with mobile phone–based patient–provider communication for adult cancer survivors. Their findings showed that individuals with higher health literacy were more likely to use mobile platforms, such as email and text messaging, to communicate with healthcare providers (Jiang & Hong, 2018). Krieger et al. (2016) identified the tailored use of metaphors as a helpful strategy for communicating complicated information to individuals with low functional health literacy. The authors compared the use of plain language with metaphors, such as the chance a pregnant woman would have a female child, to explain randomization procedures in clinical trials. Health literacy level moderated participants’ comprehension of randomization, and using metaphors resulted in better comprehension than plain language for individuals with lower health literacy (Krieger et al., 2016).

Factors Associated With Critical Health Literacy

Only one study measured critical health literacy by incorporating a question about medication adherence in a brief self-report measurement (Halverson et al., 2013, 2015). Six studies explored how functional health literacy influences critical health literacy outcomes, the most common being treatment decision making (Busch et al., 2015; Halverson et al., 2013, 2015; Keim-Malpass et al., 2018; Livaudais et al., 2013; Martinez-Donate et al., 2013). One study found no relationship between health literacy and surgical treatment decisions in women with breast cancer (Keim-Malpass et al., 2018), and another found that health literacy was positively associated with participants deciding to receive chemotherapy for advanced-stage lung or colorectal cancer (Busch et al., 2015). Low health literacy was also positively associated with decision dissatisfaction and regret (Hawley et al., 2008), as well as participants’ perception of how much responsibility they bore for treatment decision making (Livaudais et al., 2013). From the analysis of the qualitative data obtained in their mixed-methods study, Martinez-Donate et al. (2013) reported that health literacy was a factor in the need for decisional support in adults with cancer. Health literacy was also found to be related to confidence to self-manage treatment side effects (Salgado et al., 2017).

Discussion

This integrative review sought to explore what is known about health literacy in U.S. adults with cancer, with emphasis on Nutbeam’s (2000, 2008) conceptualization of health literacy. Findings from this review revealed that health literacy is widely operationalized in definition and measurement as functional skills, such as reading and completing medical forms, which is consistent with much of health literacy research in general. At its inception in the 1970s, the concept of health literacy was based on the recognition of a gap between the readability of health information and patients’ comprehension abilities (Doak & Doak, 1980). This resulted in a proliferation of research focused on the link between functional literacy skills and health outcomes, which resulted in the development of instruments aimed at measuring reading, writing, and comprehension abilities. Two of these instruments—REALM and S-TOFHLA—have widely been considered the gold standard for health literacy measurement (Haun, Luther, Dodd, & Donaldson, 2012). Many researchers have begun using self-report health literacy measurement tools that can be quickly and easily administered, such as the brief screener developed by Chew et al. (2004). Although these screening tools offer obvious benefits for identifying patients with inadequate health literacy in clinical settings, their usefulness for research is not as clear because they have been adapted and applied in multiple ways across studies. For example, among the studies in the current review that used the brief screener, there was no consistency in how it was scored, making it difficult to compare and synthesize results.

Defining and measuring health literacy merely in terms of functional skills presents certain limitations for health literacy research. First, this approach lacks attention to contextual factors that may influence the process of obtaining, comprehending, and applying health information (Chinn & McCarthy, 2013; Nutbeam, 2008; Paasche-Orlow & Wolf, 2007; Rudd, 2015; Sørensen et al., 2012; Squiers, Peinado, Berkman, Boudewyns, & McCormack, 2012). Second, functional health literacy is often conceptualized as a risk, in which an individual with low health literacy is at higher risk for poor health outcomes (Nutbeam, 2008; Pizur-Barnekow, Darragh, & Johnston, 2011). Finally, health literacy is narrowly referred to as a characteristic of individual patients, overlooking the role of caregivers, healthcare providers, and the wider healthcare system (Chinn & McCarthy, 2013; Paasche-Orlow & Wolf, 2007; Rudd, 2015; Squiers et al., 2012). These shortcomings have led to disparate findings among studies exploring functional health literacy skills in various populations.

In this review, functional health literacy was associated with patients’ knowledge about cancer and treatment options, but not with perceived information needs, comprehension of expected treatment outcomes, and physical well-being. This is consistent with research involving patients with other long-term illnesses, such as diabetes and chronic kidney disease, in which studies have linked functional health literacy to disease knowledge (Chen et al., 2018; van der Heide et al., 2014). Some studies identified relationships between functional health literacy and outcomes, such as glycemic control (Niknami et al., 2018; Saeed, Saleem, Naeem, Shahzadi, & Islam, 2018; van der Heide et al., 2014) and medication adherence (Fan, Lyons, Goodman, Blanchard, & Kaphingst, 2016), but others found that functional health literacy was not associated with these same outcomes (Al Sayah, Majumdar, Egede, & Johnson, 2015; Chen et al., 2018). Although the inconsistencies of these reports highlight the importance of measuring more than only functional health literacy skills, they also substantiate the need to address the multidimensional nature of health literacy in research and practice.

Scholars have brought attention to the need for a more comprehensive definition of health literacy that encompasses more than functional literacy (Pleasant, 2014; Rudd, 2015; Sørensen et al., 2012; Squiers et al., 2012). Many definitions exist in the literature, and, although most have overlapping features, there is little agreement on the specific attributes that constitute health literacy. This causes wide variations in how the concept is operationalized, leading to the development of more than 100 different measurement tools with varied purposes and results. Nutbeam’s (2000, 2008) framework provides a conceptualization of health literacy that addresses the limitations of research focused primarily on functional health literacy. An explicit assumption of Nutbeam’s (2000, 2008) framework is that health literacy is an asset for patient empowerment rather than a risk for negative health outcomes (Nutbeam, 2008). The hierarchical structure of the three levels of health literacy indicates that individuals can develop progressively higher skills, ultimately leading to personal autonomy and empowerment. Advancement through the levels is influenced by personal factors—cognition, social skills, and self-efficacy—as well as the content and method of communication from healthcare providers (Nutbeam, 2000). The framework was initially developed for use in public health, but there is growing empirical support for its use in health literacy research across various settings. Much of this work has been done outside of the United States. In Australia, Osborne, Batterham, Elsworth, Hawkins, and Buchbinder (2013) developed the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ), a valid and reliable instrument that addresses each of the dimensions of health literacy outlined by Nutbeam (2000, 2008). Findings from studies using the HLQ have highlighted its usefulness in measuring all three levels of health literacy and identifying health literacy needs that can be addressed in the clinical setting, particularly with regard to effective communication between patients with cancer and healthcare providers (Goodwin et al., 2018; Hawkins, Gill, Batterham, Elsworth, & Osborne, 2017; Kayser, Hansen-Nord, Osborne, Tjønneland, & Hansen, 2015; Osborne et al., 2013).

Consistent with the wider body of health literacy research, critical health literacy in adults with cancer is often captured in outcomes, such as self-efficacy, self-management, adherence, and decision making. Far fewer studies have actually measured critical health literacy, but those that have measured it have found positive correlations with disease-specific outcomes (Lai, Ishikawa, Kiuchi, Mooppil, & Griva, 2013; McKenna, Sixsmith, & Barry, 2017). Similarly, scant attention is given to the role of interactive health literacy in adult oncology research. None of the 22 reviewed studies measured interactive health literacy, and only three addressed it at all. However, several national agencies emphasize the importance of clear communication between healthcare providers and patients; in fact, the majority of recommended health literacy strategies revolve around communication of health information (e.g., teach-back method, Ask Me 3®, Health Literacy Universal Precautions). This necessitates research focused on interactive health literacy, particularly as patients are facing increasing demands to self-manage complex health conditions, such as cancer. Researchers have begun to develop and test more comprehensive measures of health literacy, such as the Functional Communicative and Critical Health Literacy (FCCHL) scale (Ishikawa, Takeuchi, & Yano, 2008). Studies using this scale have reported that interactive health literacy was more strongly correlated than the other levels of health literacy with self-management and patients’ confidence in healthcare interactions (Heijmans, Waverijn, Rademakers, van der Vaart, & Rijken, 2015), as well as with effective patient–provider communication (Inoue, Takahashi, & Kai, 2013).

The significance of health literacy–sensitive communication is reflected in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ landmark report entitled National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy (ODPH, 2010). Its recommendations stem from the synthesis of evidence related to health literacy improvement into a comprehensive framework with broad goals, as well as specific strategies. The overarching vision of the action plan is to create a health literate society that “provides everyone with access to accurate and actionable health information, and delivers person-centered health information and services” (ODPH, 2010, p. 1). One approach to ensuring access to actionable health information is through the use of the Health Literacy Universal Precautions toolkit by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Health Literacy Universal Precautions involves delivering health information under the assumption that all healthcare consumers have limited health literacy and would benefit from clear communication. AHRQ cites evidence that healthcare providers do not consistently recognize when a patient or caregiver lacks adequate health literacy and that stressful situations, such as serious illness, often impair the ability to understand and apply health information successfully (Brega et al., 2015). Health Literacy Universal Precautions address health literacy limitations by communicating clearly with all consumers, ensuring they understand necessary information, and simplifying navigation of the healthcare environment (Brega et al., 2015).

Limitations

Limitations of this review include the use of a single reviewer and a single database, which introduces a risk for potential bias. Limiting the review to U.S. research excluded important global efforts to address health literacy, particularly with regard to broader conceptualizations and measures of health literacy beyond functional skills. Theoretical literature was systematically excluded by the inclusion criteria that required measurement of health literacy, resulting in a lack of diversity in the types of studies included. This may have resulted in the omission of important insights into the complexities of health literacy published in non-nursing journals.

Implications for Nursing

Health literacy is recognized as an integral component of patient-centered care in the United States. Advances in medicine and technology, combined with efforts to reduce healthcare spending, have resulted in high expectations for patients to access, comprehend, and apply a great deal of complex information to their own situations. These situations are often associated with distressing health crises, such as cancer, in which the psychological effect of a life-threatening diagnosis may reduce one’s ability to process new information. This challenge for patients and their families has significant implications for healthcare providers as they seek to facilitate self-management and decision making in the context of complex illnesses. Nurses, who provide the bulk of bedside patient care and education, are uniquely positioned to effect change on multiple levels by engendering greater understanding of what health literacy means in clinical practice and in research. In practice, oncology nurses must advocate for all information to be accessible and actionable, using an approach like the Health Literacy Universal Precautions toolkit. As patients are increasingly expected to engage in healthcare—from self-assessment using tools, such as Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®), to treatment decision making to self-management—it is vital for healthcare providers to be aware of and address health literacy in their practice. These efforts will require intentional collaboration among multiple healthcare disciplines, system administrators, policymakers, patients, and caregivers.

In research, there is an urgency to expand current knowledge about the role of health literacy to improve the quality, safety, and effectiveness of cancer care. This integrative review highlights the lack of adequate attention given to racial and ethnic differences related to health literacy in adult oncology. In addition, most of the studies were limited with regard to number of cancer diagnoses, indicating a need to expand research to all types of cancer. Other areas to be considered for future research include the role of caregivers in health literacy, technology-based health literacy tools, and the association between health literacy and self-management of illness. Self-management is a key aspect of cancer care because patients face myriad symptoms of disease, as well as treatment side effects. Health literacy and self-management are considered current research priorities, but there is relatively little clear evidence of how these two phenomena relate to each other, particularly for patients with cancer. Research should be conducted using a comprehensive definition of health literacy, such as Nutbeam’s (2000, 2008) framework, and corresponding measurement tools that address the multiple aspects of health literacy, such as the HLQ. With an expanded understanding of the multidimensional nature of health literacy, it is essential to incorporate interactive and critical health literacy into studies to comprehensively capture how patients process and apply cancer-related information for self-management. This will provide valuable insight to guide the development of evidence-based interventions that facilitate effective self-management for adults with cancer.

Patients with cancer are often overwhelmed by the amount of information about their disease, decisions that must be made regarding treatment options, and self-management needs. This often leads to considerable involvement of caregivers, who may assist patients in obtaining, processing, and applying health information (Edwards, Wood, Davies, & Edwards, 2015; Goldsmith, Wittenberg, Platt, Iannarino, & Reno, 2016; Wittenberg, Goldsmith, Ferrell, & Ragan, 2017). As a result, it is important to understand and address the health literacy of caregivers and communication patterns among patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers. Researchers have begun to develop models specifically focused on these phenomena, which will need further studies to provide empirical support and refinement (Goldsmith et al., 2016; Wittenberg et al., 2017; Yuen et al., 2016). As technology assumes a larger role in daily life, it will be important to consider the health literacy implications of technology-based healthcare tools used for accessing, interpreting, and applying health information, such as patient portals (Coughlin, Stewart, Young, Heboyan, & De Leo, 2018) and mobile applications (Mirkovic, Kaufman, & Ruland, 2014). These examples provide significant opportunities for additional research to gain deeper insight into how health literacy interacts with technology in the context of cancer care.

Conclusion

Understanding the complexities of health literacy is critical to ensuring patients are receiving safe, effective, and quality healthcare, particularly in the context of a serious illness, such as cancer. Health literacy researchers must continue to refine, expand, and support evidence-based conceptual frameworks to guide the development of clinically feasible strategies that measure and address health literacy and its interconnections with other phenomena. Deepening the knowledge base will particularly benefit oncology nurses, who hold a unique position with which to champion health literacy in cancer care and ensure that the full scope of patients’ information needs are met.

About the Author(s)

Julie Kieffer Campbell, BSN, RN, is a PhD student in the College of Nursing at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. No financial relationships to disclose. Campbell can be reached at campb356@uwm.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted May 2019. Accepted July 29, 2019.)

References

Al Sayah, F., Majumdar, S.R., Egede, L.E., & Johnson, J.A. (2015). Associations between health literacy and health outcomes in a predominantly low-income African American population with type 2 diabetes. Journal of Health Communication, 20, 581–588. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1012235

Bennett, C.L., Ferreira, M.R., Davis, T.C., Kaplan, J., Weinberger, M., Kuzel, T., . . . Sartor, O. (1998). Relation between literacy, race, and stage of presentation among low-income patients with prostate cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 16, 3101–3104. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1998.16.9.3101

Brega, A.G., Barnard, J., Mabachi, N., Weiss, B.D., DeWalt, D.A., Brach, C., . . . West, D.R. (2015). AHRQ health literacy universal precautions toolkit (2nd ed.). Retrieved from https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/publications/files/healthlitto…

Busch, E.L., Martin, C., DeWalt, D.A., & Sandler, R.S. (2015). Functional health literacy, chemotherapy decisions, and outcomes among a colorectal cancer cohort. Cancer Control, 22, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/107327481502200112

Chen, Y.-C., Chang, L.-C., Liu, C.-Y., Ho, Y.-F., Weng, S.-C., & Tsai, T.-I. (2018). The roles of social support and health literacy in self-management among patients With chronic kidney disease. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 50, 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12377

Chew, L.D., Bradley, K.A., & Boyko, E.J. (2004). Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Family Medicine, 36, 588–594.

Chinn, D., & McCarthy, C. (2013). All Aspects of Health Literacy Scale (AAHLS): Developing a tool to measure functional, communicative and critical health literacy in primary healthcare settings. Patient Education and Counseling, 90, 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.019

Coughlin, S.S., Stewart, J.L., Young, L., Heboyan, V., & De Leo, G. (2018). Health literacy and patient web portals. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 113, 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.02.009

Dearholt, S.L., & Dang, D. (2012). Johns Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice: Model and guidelines. Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International.

Doak, L.G., & Doak, C.C. (1980). Patient comprehension profiles: Recent findings and strategies. Patient Counseling and Health Education, 3, 101–106.

Edwards, M., Wood, F., Davies, M., & Edwards, A. (2015). “Distributed health literacy”: Longitudinal qualitative analysis of the roles of health literacy mediators and social networks of people living with a long-term health condition. Health Expectations, 18, 1180–1193. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12093

Fan, J.H., Lyons, S.A., Goodman, M.S., Blanchard, M.S., & Kaphingst, K.A. (2016). Relationship between health literacy and unintentional and intentional medication nonadherence in medically underserved patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educator, 42, 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721715624969

Freedman, R.A., Kouri, E.M., West, D.W., & Keating, N.L. (2015). Racial/ethnic disparities in knowledge about one’s breast cancer characteristics. Cancer, 121, 724–732. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28977

Giuse, N.B., Kusnoor, S.V, Koonce, T.Y., Naylor, H.M., Chen, S.C., Blasingame, M.N., . . . Lovly, C.M. (2016). Guiding oncology patients through the maze of precision medicine. Journal of Health Communication, 21(Suppl. 1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1131772

Goldsmith, J., Wittenberg, E., Platt, C.S., Iannarino, N.T., & Reno, J. (2016). Family caregiver communication in oncology: Advancing a typology. Psycho-Oncology, 25, 463–470. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3862

Goodwin, B.C., March, S., Zajdlewicz, L., Osborne, R.H., Dunn, J., & Chambers, S.K. (2018). Health literacy and the health status of men with prostate cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 27, 2374–2381. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4834

Halverson, J., Martinez-Donate, A., Trentham-Dietz, A., Walsh, M.C., Schaaf Strickland, J.S., Palta, M., . . . Cleary, J. (2013). Health literacy and urbanicity among cancer patients. Journal of Rural Health, 29, 392–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12018

Halverson, J.L., Martinez-Donate, A.P., Palta, M., Leal, T., Lubner, S., Walsh, M.C., . . . Trentham-Dietz, A. (2015). Health literacy and health-related quality of life among a population-based sample of cancer patients. Journal of Health Communication, 20, 1320–1329. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2015.1018638

Haun, J., Luther, S., Dodd, V., & Donaldson, P. (2012). Measurement variation across health literacy assessments: Implications for assessment selection in research and practice. Journal of Health Communication, 17(Suppl. 3), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.712615

Hawkins, M., Gill, S.D., Batterham, R., Elsworth, G.R., & Osborne, R.H. (2017). The Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) at the patient-clinician interface: A qualitative study of what patients and clinicians mean by their HLQ scores. BMC Health Services Research, 17, 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2254-8

Hawley, S.T., Janz, N.K., Hamilton, A., Griggs, J.J., Alderman, A.K., Mujahid, M., & Katz, S.J. (2008). Latina patient perspectives about informed treatment decision making for breast cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 73, 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.036

Hawley, S.T., Janz, N.K., Lillie, S.E., Friese, C.R., Griggs, J.J., Graff, J.J., . . . Katz, S.J. (2010). Perceptions of care coordination in a population-based sample of diverse breast cancer patients. Patient Education and Counseling, 81(Suppl. 1), S34–S40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2010.08.009

Heijmans, M., Waverijn, G., Rademakers, J., van der Vaart, R., & Rijken, M. (2015). Functional, communicative and critical health literacy of chronic disease patients and their importance for self-management. Patient Education and Counseling, 98, 41–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.10.006

Helitzer, D., Hollis, C., Sanders, M., & Roybal, S. (2012). Addressing the “other” health literacy competencies–Knowledge, dispositions, and oral/aural communication: Development of TALKDOC, an intervention assessment tool. Journal of Health Communication, 17(Suppl. 3), 160–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.712613

Hendren, S., Chin, N., Fisher, S., Winters, P., Griggs, J., Mohile, S., & Fiscella, K. (2011). Patients’ barriers to receipt of cancer care, and factors associated with needing more assistance from a patient navigator. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103, 701–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0027-9684(15)30409-0

Husson, O., Mols, F., Fransen, M.P., van de Poll-Franse, L.V., & Ezendam, N.P.M. (2014). Low subjective health literacy is associated with adverse health behaviors and worse health-related quality of life among colorectal cancer survivors: Results from the profiles registry. Psycho-Oncology, 24, 478–486. http://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3678

Inglehart, R.C., Taberna, M., Pickard, R.K., Hoff, M., Fakhry, C., Ozer, E., . . . Gillison, M.L. (2016). HPV knowledge gaps and information seeking by oral cancer patients. Oral Oncology, 63, 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.10.021

Inoue, M., Takahashi, M., & Kai, I. (2013). Impact of communicative and critical health literacy on understanding of diabetes care and self-efficacy in diabetes management: A cross-sectional study of primary care in Japan. BMC Family Practice, 14, 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-40

Ishikawa, H., Takeuchi, T., & Yano, E. (2008). Measuring functional, communicative, and critical health literacy among diabetic patients. Diabetes Care, 31, 874–879. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc07-1932

Jiang, S., & Hong, Y.A. (2018). Mobile-based patient-provider communication in cancer survivors: The roles of health literacy and patient activation. Psycho-Oncology, 27, 886–891. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4598

Kayser, L., Hansen-Nord, N.S., Osborne, R.H., Tjønneland, A., & Hansen, R.D. (2015). Responses and relationship dynamics of men and their spouses during active surveillance for prostate cancer: Health literacy as an inquiry framework. BMC Public Health, 15, 741–750. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2068-8

Keim-Malpass, J., Doede, A., Camacho, F., Kennedy, C., & Showalter, S.L. (2018). Impact of patient health literacy on surgical treatment of breast cancer. Breast Journal, 24, 633–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.13011

Koay, K., Schofield, P., & Jefford, M. (2012). Importance of health literacy in oncology. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology, 8, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-7563.2012.01522.x

Krieger, J.L., Neil, J.M., Strekalova, Y.A., & Sarge, M.A. (2016). Linguistic strategies for improving informed consent in clinical trials among low health literacy patients. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 109, djw233. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djw233

Kutner, M., Greenberg, E., Jin, Y., & Paulsen, C. (2006). The health literacy of America’s adults: Results from the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483_1.pdf

Lai, A.Y., Ishikawa, H., Kiuchi, T., Mooppil, N., & Griva, K. (2013). Communicative and critical health literacy, and self-management behaviors in end-stage renal disease patients with diabetes on hemodialysis. Patient Education and Counseling, 91, 221–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.12.018

Livaudais, J.C., Franco, R., Fei, K., & Bickell, N.A. (2013). Breast cancer treatment decision-making: Are we asking too much of patients? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 28, 630–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2274-3

Martinez-Donate, A.P., Halverson, J., Simon, N.-J., Strickland, J.S., Trentham-Dietz, A., Smith, P.D., . . . Wang, X. (2013). Identifying health literacy and health system navigation needs among rural cancer patients: Findings from the Rural Oncology Literacy Enhancement Study (ROLES). Journal of Cancer Education, 28, 573–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-013-0505-x

Matsuyama, R.K., Kuhn, L.A., Molisani, A., & Wilson-Genderson, M.C. (2013). Cancer patients’ information needs the first nine months after diagnosis. Patient Education and Counseling, 90, 96–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2012.09.009

Matsuyama, R.K., Wilson-Genderson, M., Kuhn, L., Moghanaki, D., Vachhani, H., & Paasche-Orlow, M. (2011). Education level, not health literacy, associated with information needs for patients with cancer. Patient Education and Counseling, 85, e229–e236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.03.022

McKenna, V.B., Sixsmith, J., & Barry, M.M. (2017). The relevance of context in understanding health literacy skills: Findings from a qualitative study. Health Expectations, 20, 1049–1060. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12547

Mirkovic, J., Kaufman, D.R., & Ruland, C.M. (2014). Supporting cancer patients in illness management: Usability evaluation of a mobile app. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 16(8), E33–E58. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.3359

Mohan, R., Beydoun, H., Barnes-Ely, M.L., Lee, L., Davis, J.W., Lance, R., & Schellhammer, P. (2009). Patients’ survival expectations before localized prostate cancer treatment by treatment status. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 22, 247–256. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2009.03.080200

National Cancer Institute. (2018). Cancer statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/statistics

National Cancer Institute. (2019). Cancer stat facts: Oral cavity and pharynx cancer. Retrieved from https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/oralcav.html

Nielsen-Bohlman, L., Panzer, A.M., & Kindig, D.A. (2004). Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Niknami, M., Mirbalouchzehi, A., Zareban, I., Kalkalinia, E., Rikhtgarha, G., & Hosseinzadeh, H. (2018). Association of health literacy with type 2 diabetes mellitus self-management and clinical outcomes within the primary care setting of Iran. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 24, 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1071/PY17064

Nutbeam, D. (2000). Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International, 15, 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/15.3.259

Nutbeam, D. (2008). The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science and Medicine, 67, 2072–2078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050

Office of Disease Prevention and Health. (2010). National action plan to improve health literacy. Retrieved from https://health.gov/communication/initiatives/health-literacy-action-pla…

Osborne, R.H., Batterham, R.W., Elsworth, G.R., Hawkins, M., & Buchbinder, R. (2013). The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC Public Health, 13, 658–674. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-658

Paasche-Orlow, M.K., & Wolf, M.S. (2007). The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. American Journal of Health Behavior, 31(Suppl. 1), S19–S26. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.31.s1.4

Pickard, A.S., Lin, H.W., Knight, S.J., Sharifi, R., Wu, Z., Hung, S.Y., . . . Bennett, C.L. (2009). Proxy assessment of health-related quality of life in African American and white respondents with prostate cancer: Perspective matters. Medical Care, 47, 176–183. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-658

Pizur-Barnekow, K., Darragh, A., & Johnston, M. (2011). “I cried because I didn’t know if I could take care of him”: Toward a taxonomy of interactive and critical health literacy as portrayed by caregivers of children with special health care needs. Journal of Health Communication, 16(Suppl. 3), 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2011.604386

Pleasant, A. (2014). Advancing health literacy measurement: A pathway to better health and health system performance. Journal of Health Communication, 19, 1481–1496. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.954083

Rudd, R.E. (2015). The evolving concept of health literacy: New directions for health literacy studies. Journal of Communication in Healthcare, 8, 7–9. https://doi.org/10.1179/1753806815Z.000000000105

Saeed, H., Saleem, Z., Naeem, R., Shahzadi, I., & Islam, M. (2018). Impact of health literacy on diabetes outcomes: A cross-sectional study from Lahore, Pakistan. Public Health, 156, 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.12.005

Salgado, T.M., Mackler, E., Severson, J.A., Lindsay, J., Batra, P., Petersen, L., & Farris, K.B. (2017). The relationship between patient activation, confidence to self-manage side effects, and adherence to oral oncolytics: A pilot study with Michigan oncology practices. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25, 1797–1807. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3584-0

Song, L., Mishel, M., Bensen, J.T., Chen, R.C., Knafl, G.J., Blackard, B., . . . Godley, P.A. (2012). How does health literacy affect quality of life among men with newly diagnosed clinically localized prostate cancer? Findings from the North Carolina–Louisiana Prostate Cancer Project (PCaP). Cancer, 118, 3842–3851. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.26713

Song, L., Weaver, M.A., Chen, R.C., Bensen, J.T., Fontham, E., Mohler, J.L., . . . Sleath, B. (2014). Associations between patient–provider communication and socio-cultural factors in prostate cancer patients: A cross-sectional evaluation of racial differences. Patient Education and Counseling, 97, 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.08.019

Sørensen, K., Van den Broucke, S., Fullam, J., Doyle, G., Pelikan, J., Slonska, Z., & Brand, H. (2012). Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health, 12, 80. https://doi.org/1471-2458-12-80

Squiers, L., Peinado, S., Berkman, N., Boudewyns, V., & McCormack, L. (2012). The health literacy skills framework. Journal of Health Communication, 17(Suppl. 3), 30–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2012.713442

van der Heide, I., Uiters, E., Rademakers, J., Struijs, J.N., Schuit, A.J., & Baan, C.A. (2014). Associations among health literacy, diabetes knowledge, and self-management behavior in adults with diabetes: Results of a Dutch cross-sectional study. Journal of Health Communication, 19(Suppl. 2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2014.936989

Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52, 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

Wittenberg, E., Goldsmith, J., Ferrell, B., & Ragan, S.L. (2017). Promoting improved family caregiver health literacy: Evaluation of caregiver communication resources. Psycho-Oncology, 26, 935–942. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4117

Yuen, E.Y., Dodson, S., Batterham, R.W., Knight, T., Chirgwin, J., & Livingston, P.M. (2016). Development of a conceptual model of cancer caregiver health literacy. European Journal of Cancer Care, 25, 294–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12284