ONS Guidelines™ for Cancer Treatment–Related Radiodermatitis

Purpose: Radiodermatitis is a side effect of radiation therapy. Evidence-based interventions to minimize severity or delay progression are important for clinical care. This guideline intends to support individuals with cancer, clinicians, and others in decisions regarding radiodermatitis treatment.

Methodologic Approach: A panel of healthcare professionals with patient representation was convened to develop a national clinical practice guideline for the management of radiodermatitis. GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodology and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine criteria for trustworthy guidelines were followed. The Cochrane Collaboration risk-of-bias tool was used, and certainty of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach. A quantitative and narrative synthesis of the evidence was completed.

Findings: The panel agreed on eight recommendations and made a conditional recommendation for deodorant/antiperspirant. Aloe vera and oral curcumin had knowledge gaps and were recommended only in the context of a clinical trial. The panel suggested against emu oil, calendula, and nonsteroidal interventions.

Implications for Nursing: This guideline summarizes evidence-based interventions for the management of radiodermatitis to guide clinical care.

Supplementary material can be found at https://bit.ly/2GEwJtT

Jump to a section

About 1.8 million people will be diagnosed with cancer in the United States in 2020, and about 50%–70% of them will receive radiation therapy (American Cancer Society, 2020; Ballas et al., 2006; Wei et al., 2019). Radiation therapy can lead to acute and late side effects. Radiodermatitis, sometimes referred to as radiation-induced skin reactions or radiation dermatitis, is one of the most reported side effects of radiation therapy that can affect as many as 95% of patients across treatment sites (Gewandter et al., 2013; Gosselin et al., 2010). Radiodermatitis can have a minimal to significant impact on a patient’s quality of life and may also have associated out-of-pocket costs (Schnur et al., 2012). In a nationwide survey of patient perspectives of treatment, 16% of patients who received radiation therapy reported that their skin burning was worse than they expected, 39% reported it being not as bad or the same as expected, and 45% did not experience any skin burning (Shaverdian et al., 2019).

Factors that contribute to radiodermatitis include treatment volume, daily dosage and total dose, energy and type of radiation therapy, and total treatment time (Gosselin et al., 2010). Individual factors associated with developing radiodermatitis include higher body mass index, smoking, older age, and genetic variants (Mumbrekar et al., 2017; Sharp, Johansson, et al., 2013). In addition, other treatment modalities may also put a patient at risk for radiodermatitis.

Several grading and assessment tools are commonly used to document skin changes during radiation therapy and are important to use for consistency and continuity of management during and after radiation therapy. The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) grading system includes a 0–4 scale based on objective skin changes, with RTOG 0 being no visible change to the skin and RTOG 4 being ulceration, bleeding, or necrosis (Cox et al., 1995). The RTOG scale does not account for subjective aspects of skin damage, including discomfort or pain. The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events is a standardized classification tool that can be used by healthcare clinicians to rate the severity of radiodermatitis (National Cancer Institute, 2017). The scale ranges from grade 1 to grade 5, with grade 1 being faint erythema or dry desquamation. The grades are progressive, and grades 2 and 3 incorporate moist desquamation, which can often cause discomfort and pain. Consistent use of a tool is critical across clinical studies and patient care, so as modalities and fractionation schemas change, radiodermatitis can be better understood and managed.

A variety of herbal, topical, endogenous, pharmaceutical, ointment, and dressing products have been studied prophylactically to minimize the development of radiodermatitis, as well to treat radiodermatitis after it occurs. Many of these products are also available to patients over the counter and can range in cost, often leaving the consumer at a disadvantage with knowing which is best. As understanding of the skin microbiome and ionizing radiation improves, so should the treatment of radiodermatitis. Current practice differs by clinical site and provider preference and is based on mixed findings from previous research (Gosselin et al., 2010; Hoopfer et al., 2015; Kodiyan & Amber, 2015; Loewenthal, 1949; Williams et al., 1996). As research has evolved from case control to descriptive and now to interventional approaches, it is critical that methods and outcomes help to discern which products should be used for patient care and which should not be studied further. The purpose of these guidelines is to provide evidence-based recommendations for patients and frontline clinicians.

Aim and Objectives

The aim of this guideline is to provide evidence-based symptom management recommendations for individuals who are receiving radiation therapy and are at risk for radiodermatitis. The guideline incorporates the most recently published research on interventions for the management of radiodermatitis during and after cancer treatment. The target audience includes oncology healthcare professionals, patients, and decision makers. Policymakers interested in this guideline include individuals and organizations developing local, national, or international protocols with a goal of improving management of radiodermatitis in adults with cancer. The guideline is based on a systematic review and meta-analysis that explored the following research question: What are the evidence-based recommended interventions for the management and treatment of radiodermatitis in patients with cancer?

Guideline Development Methods

The Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) vetted and appointed individuals to the ONS Guidelines™ panel. The membership of the interprofessional panel included oncology nurses at all levels of practice and inquiry, radiation oncologists, and a patient representative (see online Appendix). The panel was coordinated by the senior manager of evidence-based practice at ONS (P.K.G.), with collaboration from a GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodologist (R.L.M.). The evidence synthesis for this guideline was based on a rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis (Ginex et al., 2020). The panel completed its work using online and face-to-face meetings and web-based tools (www.gradepro.org), with one two-day in-person meeting to review the evidence and formulate recommendations.

The ONS Guidelines panel developed and graded the recommendations and assessed the certainty of the supporting evidence according to the GRADE approach (Guyatt, Oxman, Akl, et al., 2011; Guyatt, Oxman, Kunz, et al., 2011; Guyatt, Oxman, Sultan, et al., 2011). The guideline development process, including panel formation, management of conflicts of interest, internal and external review, and organizational approval, was guided by policies and procedures derived from the Guideline International Network (GIN) McMaster Guideline Development Checklist (https://cebgrade.mcmaster.ca/guidecheck.html) and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) criteria for trustworthy guidelines (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Schünemann et al., 2014).

Financial and intellectual disclosures of interest of all participants were collected and managed according to ONS policies and the recommendations of NASEM and GIN (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Schünemann et al., 2015). At the time of appointment and again at the recommendations meeting, disclosures were recorded and the guideline panel had no relevant conflicts of interest (no material interest in any commercial entity with a product that could be affected by the guidelines) (see online Appendix).

Formulation of Specific Clinical Questions and Determining Outcomes of Interest

The ONS Guidelines panel met remotely biweekly to discuss and prioritize clinical questions for this guideline. Panelists were instructed to identify questions that were clinically relevant—questions about radiation skin changes that patients with cancer were asking and that clinicians had uncertainty regarding the answers. The panel noted that prevention of radiodermatitis is unlikely and, therefore, focused questions on minimizing the development of radiodermatitis. Questions were formulated into PICO (patient, intervention, comparator, and outcome) components. The guideline panel selected outcomes of interest for each question a priori. The panel discussed all possible outcomes and prioritized importance for patients and decision making using the GRADE approach (Guyatt, Oxman, Kunz, et al., 2011). The panel rated the following outcomes as critical for clinical decision making across the PICO questions: time to development of radiodermatitis, pain, pruritis, quality of life, cost, intervention adherence, and fidelity.

Literature Search and Quality Assessment

After the PICO questions were developed, a literature search was conducted to identify published systematic reviews that closely addressed the PICO questions. Panel members reviewed the results using AMSTAR 2 (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews–2) appraisal tool (Shea et al., 2017). Based on AMSTAR 2, one systematic review and meta-analysis was identified as high quality and appropriate for update (Chan et al., 2014). A medical librarian recreated the search strategies published in that article, and in addition to this update, de novo reviews were conducted for additional questions addressing the efficacy of calendula, curcumin, emu oil, and silver sulfadiazine. The searches were run from January 2012 to September 2019 and included the following databases: MEDLINE®, EMBASE®, CINAHL®, Wiley Cochrane Library, PsycINFO®, and LILACS. Full search strategies, inclusion and exclusion criteria, review methodology, corresponding PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagrams, and results are reported in the accompanying systematic review (Ginex et al., 2020).

Synthesis of Evidence and Development of Recommendations

The evidence for this guideline was based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on interventions for radiodermatitis (Ginex et al., 2020). The evidence from that review was summarized and assessed in a GRADE evidence profile. Within the evidence profile, the body of evidence across each outcome is assessed based on factors that either decrease or increase one’s certainty: risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, publication bias, large magnitude of effect, dose–response gradient, or opposing residual confounding (Balshem et al., 2011; Guyatt, Oxman, Sultan, et al., 2011). In addition to the certainty of evidence, the panel formulated recommendations considering the balance of benefits and harms, patients’ values and preferences, resource use, health equity, acceptability, and feasibility. For each question, the panel entered judgments into the GRADE Evidence-to-Decision (EtD) framework using the GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (www.gradepro.org).

During a two-day in-person meeting, the panel developed clinical recommendations based on the evidence summarized in the EtD table. For each recommendation, the panel came to a consensus on the following: the certainty in the evidence, the balance of benefits and harms of the compared intervention options, and the assumptions about the values and preferences associated with the decision. The panel also discussed the extent of the use of alternative treatment options. The panel agreed on the recommendations (including direction and strength), remarks, and qualifications by consensus vote based on the balance of all desirable and undesirable consequences. The final guidelines, including recommendations, were reviewed and approved by all members of the guideline panel.

Interpretation of Recommendations

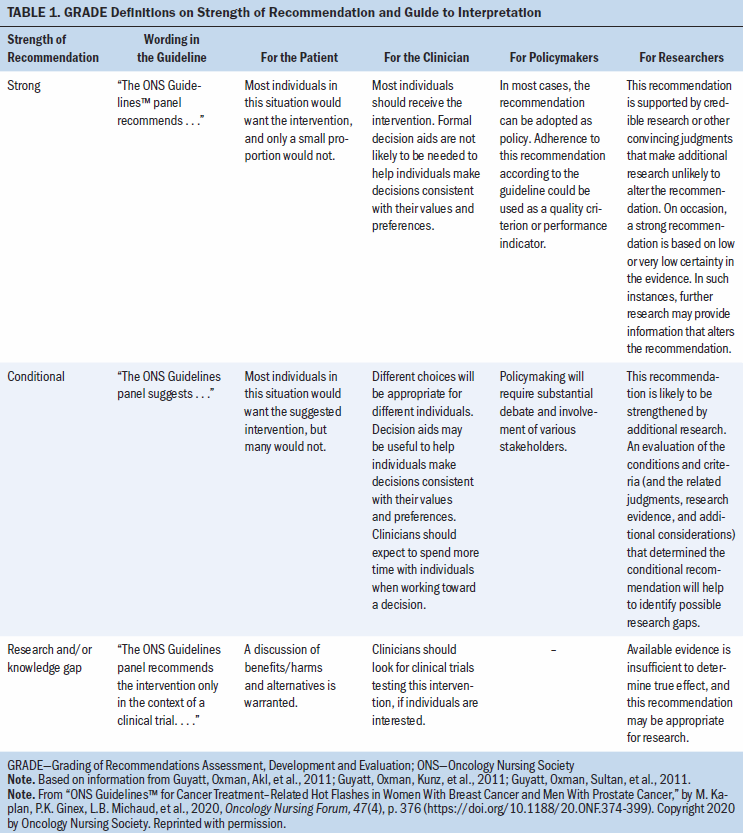

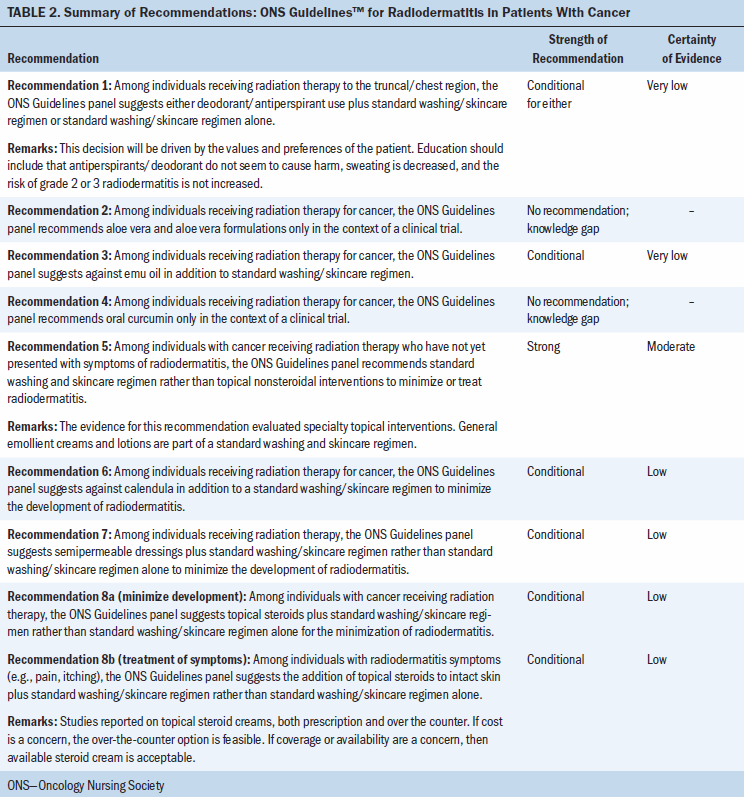

The strength of the recommendations in this guideline are labeled as strong or conditional. In some situations, the panel deemed the available evidence insufficient to determine a true effect and identified the area as a knowledge gap. Table 1 provides the general interpretation of the recommendations for patients, clinicians, healthcare policymakers, and researchers. The recommendations are summarized in Table 2.

Document Review

Draft recommendations were reviewed and approved by all members of the guideline panel and then opened for public comment from January 24 to February 7, 2020. In addition, a targeted peer review was conducted with three clinical or research experts on radiodermatitis. The goal of public comment and targeted peer review was to obtain direct feedback on the draft recommendations, as well as feedback to facilitate dissemination of the final guideline to practitioners. Following public and targeted comment, the document was revised to address pertinent comments; however, no changes were made to the recommendations. The ONS Board of Directors reviewed and approved the guideline methodology and process. The guidelines were then submitted to the Oncology Nursing Forum for peer review.

How to Use These Guidelines

ONS Guidelines are intended to assist clinicians in making decisions about treatment interventions for common symptoms experienced by patients with cancer throughout the treatment trajectory. ONS Guidelines are intended to inform education, identify research gaps, and promote policy and advocacy. They may also be used by patients in collaboration with their healthcare team. ONS Guidelines are not medical advice and do not replace care by a cancer care clinician. Using a shared decision-making process, clinicians make decisions with patients, including discussion of patients’ values and preferences with respect to their current situation. ONS Guidelines may not include all available treatments for an individual patient. Treatments described in the ONS Guidelines may not be appropriate for all patients or in all scenarios. As scientific advances and new evidence become available, these ONS Guidelines may become outdated. Following these ONS Guidelines does not guarantee improvement or a successful outcome. ONS does not warrant or guarantee any products described.

Implementation of ONS Guidelines will be facilitated by forthcoming dissemination tools and patient education resources. The use of ONS Guidelines will also be facilitated by the links to the EtD frameworks and interactive summary of findings tables in each section.

Recommendations, Key Evidence, and Qualifying Statements

Patients should discuss their hygiene routine with their healthcare professional, recognizing that there may be differences based on the body site being radiated. Standard patient education during and following radiation therapy includes washing with a mild soap and lukewarm water and using caution when entering hot tubs, swimming in lakes, and sunbathing during and immediately after treatment (Feight et al., 2011; Rosenthal et al., 2019).

Recommendation 1: Deodorant/Antiperspirant

Should deodorant/antiperspirant in addition to normal washing be used rather than normal washing alone in individuals receiving radiation therapy for cancer in the breast/chest region?

Among individuals receiving radiation therapy to the breast/chest region, the ONS Guidelines panel suggests either deodorant/antiperspirant use in addition to standard washing/skincare regimen or standard washing/skincare regimen alone (conditional recommendation for either; very low certainty of evidence).

Remarks: This decision will be driven by the values and preferences of the patient. Education should include that deodorant/antiperspirant does not seem to cause harm, sweating is decreased, and the risk of grade 2 or 3 radiodermatitis is not increased.

Summary of the Evidence

The systematic review (Ginex et al., 2020) identified five studies (Bennett, 2009; Gee et al., 2000; Lewis et al., 2014; Théberge et al., 2009; Watson et al., 2012) that addressed this question, all in patients with breast cancer. Sample sizes ranged from 36 to 333. Lewis et al. (2014) was a three-arm study that compared aluminum deodorant to non-aluminum deodorant and included a control group that only used soap. The other four studies compared deodorant or antiperspirant to a control group of no deodorant or antiperspirant. The analysis reviewed aluminum and non-aluminum data separately and found no difference, so the pooled results are reported here for any deodorant or antiperspirant. The panel noted that this question is a concern for radiation therapy that includes the breast/chest fields only and that newer treatments have improved, so this is less of a concern clinically than it had been in the past. The panel considered research that included aluminum- and non–aluminum-containing products.

Benefits

The outcome of development of grade 2 or 3 radiodermatitis was informed by three trials (Bennett, 2009; Gee et al., 2000; Lewis et al., 2014). Individuals’ using deodorant/antiperspirant may result in no difference in the development of grade 2 radiodermatitis (risk ratio [RR] = 0.99, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.76, 1.29]; absolute risk reduction [ARR] = 3 fewer per 1,000, from 84 fewer to 101 more; low certainty of evidence). Similarly, evidence suggests that deodorant/antiperspirant use does not reduce the development of grade 3 radiodermatitis (RR = 0.74, 95% CI [0.27, 2.02]; ARR = 13 fewer per 1,000, from 37 fewer to 52 more; low certainty of evidence).

Harms and Burdens

No harms were reported from deodorant/antiperspirant use in the studies.

Certainty in the Evidence of Effects

The certainty in the estimates for deodorant/antiperspirant use was judged as low and very low because of concerns with risk of bias and for few events.

Other Evidence-to-Decision Criteria

The panel judged the desirable effects to be trivial and the undesirable effects, such as pruritus, to be trivial. The panel considered there to probably be no important uncertainty or variability in how individuals value the main outcome and that the balance of effects does not favor either deodorant/antiperspirant or no deodorant/antiperspirant. There are negligible costs and savings for the resources required, with no included studies on cost-effectiveness. The panel judged there to be no impact on equity and that deodorant/antiperspirant use is acceptable to key stakeholders and feasible to implement.

Conclusions

Based on the evidence, the panel issued a conditional recommendation for either deodorant or antiperspirant use in addition to normal washing or normal washing alone for patients receiving radiation therapy to the breast/chest fields. The panel determined that wearing deodorant or antiperspirant or not is unlikely to affect the risk of radiodermatitis, so patients receiving radiation therapy to the chest/breast can follow their normal routine. This recommendation suggests that patients have the autonomy to decide whether to wear deodorant or antiperspirant during their treatment.

Recommendation 2: Aloe Vera

Should aloe vera rather than standard of care be used to minimize the development of radiodermatitis?

Among individuals receiving radiation therapy for cancer, the ONS Guidelines panel recommends aloe vera and aloe vera formulations only in the context of a clinical trial (no recommendation; knowledge gap).

Summary of the Evidence

This question was informed by four studies (Heggie et al., 2002; Merchant et al., 2007; Olsen et al., 2001; Williams et al., 1996) in the original systematic review by Chan et al. (2014) and two studies (Haddad et al., 2013; Hoopfer et al., 2015) in the updated review by Ginex et al. (2020). Because of the heterogeneity of methods and outcomes across the studies, the results were not able to be pooled. Sample sizes ranged from 60 to 248. Included in the studies were samples of patients with breast cancer or samples that had mixed cancer diagnoses. Aloe vera was compared to a placebo, soap, no treatment, and anionic phospholipid cream. Formulations included aloe vera gel, a commercially available product that includes aloe vera, and an aloe cream prepared specifically for the study; however, no standardized dose or formulation was used across the studies.

Benefits

The review by Chan et al. (2014) did not identify any benefits of aloe vera gel when compared to no treatment or placebo. Aloe vera rather than standard of care may reduce development of grade 2 or 3 radiodermatitis at week 5 of treatment (RR = 0.22, 95% CI [0.08, 0.61]; ARR = 265 fewer per 1,000, from 312 fewer to 132 fewer; low certainty of evidence). Patients may experience less pain when using aloe vera rather than standard of care (RR = 0.8, 95% CI [0.49, 1.3]; ARR = 65 fewer per 1,000, from 166 fewer to 97 more; low certainty of evidence).

Harms and Burdens

Aloe vera may increase incidence of rash (RR = 1.9, 95% CI [1.02, 3.53]; ARR = 140 more per 1,000, from 3 more to 394 more; low certainty of evidence) and an increase in moist desquamation (RR = 1.74, 95% CI [0.68, 4.48]; ARR = 58 more per 1,000, from 25 fewer to 271 more; low certainty of evidence).

Certainty in the Evidence of Effects

The certainty in the evidence was rated as very low because of the imprecision, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias (selective reporting of outcomes).

Other Evidence-to-Decision Criteria

The panel was unable to judge the desirable effects and undesirable effects of aloe because of the lack of a standardized formula used in the research studies that were reviewed. A large variety of products are available that include aloe vera as a component, but it is difficult to compare across studies. The panel judged that there was probably no important uncertainty or variability in how much individuals valued the main outcomes. Aloe may be drying and irritate the skin, but it may appeal to individuals who would prefer a natural product. The cost would be negligible, with no studies identified on cost-effectiveness. The panel considered aloe to be acceptable to key stakeholders and feasible to implement.

Conclusions

Limited consistent evidence exists to support a recommendation for aloe vera for the treatment of radiodermatitis in patients with cancer. Based on the low quality of the evidence and the lack of standardization in the formulas included in the research, the ONS Guidelines panel was unable to determine the benefits or harms and made no recommendation for aloe vera and identified this intervention as an evidence gap that warrants further research.

Recommendation 3: Emu Oil

Should emu oil rather than standard of care be used to minimize the development of radiodermatitis?

Among individuals receiving radiation therapy for cancer, the ONS Guidelines panel suggests against emu oil in addition to standard washing/skincare regimen (conditional recommendation; very low certainty in the evidence).

Summary of the Evidence

The systematic review identified one study that informed this question (Rollmann et al., 2015). This was a single-institution pilot study of emu oil on skin-related toxicity for patients receiving radiation therapy to the breast or chest wall (Rollmann et al., 2015). Forty-five patients with breast cancer were randomized to emu oil or a placebo of cottonseed oil.

Benefits

For the outcomes of development of grade 2 or higher radiodermatitis, use of emu oil did not exclude the potential for harm (RR = 1.55, 95% CI [0.07, 35.83]; ARR = 0 fewer per 1,000; very low certainty of evidence).

Harms and Burdens

No adverse events were reported.

Certainty in the Evidence of Effects

The certainty in the estimates for emu oil were judged to be very low because of risk of bias, indirectness (i.e., only reported on grade 3 or higher radiodermatitis), and imprecision.

Other Evidence-to-Decision Criteria

The panel judged the desirable and undesirable anticipated effects to be trivial. The panel considered there to be probably no important uncertainty or variability in how much individuals value the main outcome and that the balance of effects does not favor either emu oil or the comparison. Moderate costs would be required to purchase emu oil, and no cost-effectiveness studies were identified. Equity would probably be reduced from accessibility issues because emu oil may not be available in all locations. The panel considered that emu oil is probably acceptable and feasible to implement with the consideration that some patients may not use animal products.

Conclusions

The panel acknowledged the limited evidence for emu oil and the trivial benefits and harms. In addition, emu oil may have moderate cost and possibly reduced accessibility, acceptability, and feasibility of implementation. Based on this evidence, the ONS Guidelines panel issued a conditional recommendation suggesting against the use of emu oil for the management of radiodermatitis in patients with cancer receiving radiation therapy.

Recommendation 4: Oral Curcumin

Should oral curcumin rather than standard of care be used to minimize the development of radiodermatitis?

Among individuals receiving radiation therapy for cancer, the ONS Guidelines panel recommends oral curcumin only in the context of a clinical trial (no recommendation; knowledge gap).

Summary of the Evidence

The systematic review (Ginex et al., 2020) was informed by two studies (Ryan et al., 2013; Ryan Wolf et al., 2018) that investigated oral curcumin (6 gm daily) during radiation therapy in patients with breast cancer. The sample size was 30 in the initial study and 686 in the follow-up study. Patients took four 500 mg capsules or placebo three times a day throughout radiation therapy (Ryan et al., 2013) and for an additional week post-treatment (Ryan Wolf et al., 2018).

Benefits

Oral curcumin reduced the development of moist desquamation compared to placebo (RR = 0.64, 95% CI [0.42, 0.96]; ARR = 48 fewer per 1,000, from 78 fewer to 5 fewer; very low certainty of evidence) but did not reduce radiodermatitis severity at the end of treatment compared to placebo (beta = 0.044, 95% CI [0.101, 0.188], p = 0.552) (Ryan Wolf et al., 2018).

Harms and Burdens

Curcumin has drug interactions and is contraindicated in patients on anticoagulation agents and in patients on certain chemotherapeutic agents (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, 2020). Participants were required to take four capsules three times per day, and adherence did not differ between treatment arms. A significant number of patients withdrew from the study (curcumin: 61 of 339, placebo: 47 of 338) because of nausea/diarrhea, allergy, and unspecified reasons (Ryan Wolf et al., 2018).

Certainty in the Evidence of Effects

The panel had very low certainty in the evidence of effects based on the harms, risk of bias because of lack of a standardized scale, and conflicting readings on the development of moist desquamation.

Other Evidence-to-Decision Criteria

The panel considered the desirable anticipated effects to be small and the undesirable effects to be trivial. The panel considered there to be probably no important uncertainty or variability in how much individuals value the main outcomes and was unable to determine the balance of effects because of the reporting in the studies. Moderate costs would be required for the purchase of curcumin, with no cost-effectiveness studies identified. Equity would probably be reduced because of the cost, and the panel considered that curcumin would be acceptable to key stakeholders and probably feasible to implement.

Conclusions

The panel acknowledged the measurement of moist desquamation concerns in the studies and the potential for harms, particularly interactions with other medications used for cancer treatment. Based on this evidence, the ONS Guidelines panel made no recommendation for curcumin and identified this intervention as an evidence gap.

Recommendation 5: Specialty Topical Nonsteroidal Interventions

Should specialty topical nonsteroidal interventions (e.g., creams, lotions, ointments) rather than standard of care be used to minimize radiodermatitis?

Among individuals with cancer receiving radiation therapy without symptoms of radiodermatitis, the ONS Guidelines panel recommends standard washing and skincare regimen rather than specialty topical nonsteroidal interventions to minimize radiodermatitis (strong recommendation; moderate certainty in the evidence).

Remarks: The evidence for this recommendation evaluated specialty topical interventions. General emollient creams and lotions are part of a standard washing and skincare regimen.

Summary of the Evidence

The systematic review (Ginex et al., 2020) identified three studies that informed this question (Chan et al., 2014; Laffin et al., 2015; Nasser et al., 2017). Sample sizes ranged from 23 to 255 and included a mix of cancer diagnoses and radiation fields. A variety of specialty topical nonsteroidal treatments were used in the studies, including vitamin D ointment, Cavilon™ barrier cream, and Capilen® (an oil-based emulsion containing allantoin). The panel noted that these are different from general emollient creams and lotions that are part of a standard skincare regimen. The panel at first also considered a question of specialty nonsteroidal interventions for the treatment of radiodermatitis but judged that this was not a priority question if not recommended for minimization.

Benefits

Specialty nonsteroidal interventions may reduce development of moist desquamation (RR = 0.84, 95% CI [0.46, 1.56]; ARR = 26 fewer per 1,000, from 86 fewer to 90 more; very low certainty of evidence).

Harms and Burdens

Specialty nonsteroidal interventions increased the risk of development of grade 2 or greater radiodermatitis (RR = 1.29, 95% CI [1.06, 1.57]; ARR = 197 more per 1,000, from 41 more to 388 more; moderate certainty of evidence). The risk of pruritis and pain were minimally increased with the use of specialty interventions (pruritis: RR = 1.09, 95% CI [0.95, 1.24]; ARR = 35 more per 1,000, from 19 fewer to 93 more; low certainty of evidence; pain: RR = 1.1, 95% CI [0.9, 1.35]; ARR = 35 more per 1,000, from 35 fewer to 122 more; moderate certainty of evidence). The use of specialty nonsteroidal interventions also resulted in a decrease in relief of itching (RR = 0.85, 95% CI [0.73, 0.99]; ARR = 127 fewer per 1,000, from 229 fewer to 8 fewer; very low certainty of evidence).

Certainty in the Evidence of Effects

The panel judged the certainty in the overall evidence of effects to be moderate because of the harm of developing grade 2 radiodermatitis or higher.

Other Evidence-to-Decision Criteria

The panel judged the desirable anticipated effects of specialty nonsteroidal interventions to be trivial and the undesirable anticipated effects to be moderate. The panel considered the risk of developing grade 2 or higher radiodermatitis when making this judgment. The panel judged there to be probably no important uncertainty or variability in how much individuals value the main outcome. The panel considered that some patients may want to try an intervention to “do something,” and other patients may be relieved by not being required to incorporate an intervention into their daily routine. The panel considered that the balance of effects favors the comparison. The panel judged the costs to be moderate, with moderate savings with standard skin care, and no cost-effectiveness studies identified. Equity would probably be reduced because no intervention would be recommended and patients can use their standard washing/skincare regimen. The panel considered that recommending standard skin care would probably be acceptable to key stakeholders and feasible to implement because it is current practice in many settings.

Conclusions

The panel acknowledged that there is sufficient evidence to identify important differences between specialty topical nonsteroidal creams to minimize the development of radiodermatitis and standard washing/skin care. The panel considered that general emollient creams are used as part of standard washing and skin care, but specialty/barrier creams demonstrated harms, added additional expense, and can lead to inequity because of increased cost. Based on this evidence, the ONS Guidelines panel issued a strong recommendation suggesting standard washing/skin care rather than specialty nonsteroidal interventions to minimize the development of radiodermatitis.

Recommendation 6: Calendula

Should calendula rather than standard of care be used to minimize the development of radiodermatitis?

Among individuals receiving radiation therapy for cancer, the ONS Guidelines panel suggests against calendula in addition to a standard washing/skincare regimen to minimize the development of radiodermatitis (conditional recommendation; low certainty of evidence).

Summary of the Evidence

The systematic review (Ginex et al., 2020) identified two studies that informed this question (Schneider et al., 2015; Sharp, Finnilä, et al., 2013). Schneider (2015) was an RCT that included 51 patients with cancer of the head and neck and compared calendula to essential fatty acids (the standard of care at the institution where the research was conducted). Sharp, Finnilä, et al. (2013) compared calendula to Essex (a moisturizing cream) in 420 patients with a variety of cancer diagnoses. A third study, Pommier et al. (2004), was identified but was excluded from analysis because of the use of trolamine in the control group. The ONS Guidelines panel considered that the comparison to an active control may inflate the results reported for calendula, because trolamine may increase the risk of radiodermatitis. The panel at first also considered a question of calendula for the treatment of radiodermatitis but judged that this was not a priority question after radiodermatitis has presented.

Benefits

The panel did not identify any desirable consequences of calendula compared with standard washing/skin care.

Harms and Burdens

Calendula may increase the risk of the development of grade 2 or greater radiodermatitis (RR = 1.21, 95% CI [0.83, 1.77]; ARR = 36 more per 1,000, from 29 fewer to 131 more; low certainty of evidence) (Schneider, 2015; Sharp, Finnilä, et al., 2013).

Certainty in the Evidence of Effects

The panel judged the certainty in the overall evidence of effects to be low because of concerns with imprecision and the potential for benefits and harms.

Other Evidence-to-Decision Criteria

The panel was unable to judge desirable effects of calendula from the evaluated research and judged the undesirable effects to be trivial and that there is probably no important uncertainty or variability in how much individuals value the main outcome. Based on the harms, the panel considered that the balance of effects probably favors the comparison of standard washing and skin care. Calendula may have negligible costs and savings, with no cost-effectiveness studies identified. Equity would probably be reduced because this would be an out-of-pocket cost for patients, and the panel considered calendula to be acceptable to key stakeholders and feasible to implement. The panel considered that specific products were studied, but different formulations of calendula are available, as well as creams with calendula as a component of the formulation.

Conclusions

The panel acknowledged the limited evidence for calendula and the unknown benefits with trivial harms. In addition, calendula may have moderate cost and possibly reduced accessibility, acceptability, and feasibility of implementation. Based on this evidence, the ONS Guidelines panel issued a conditional recommendation suggesting standard of care rather than calendula for the management of radiodermatitis in patients with cancer receiving radiation therapy.

Recommendation 7: Semipermeable Dressings

Initially, the panel identified a question regarding the use of silver sulfadiazine to treat moist desquamation; however, the panel also recognized that for many practice sites silver sulfadiazine is currently considered the standard of care for patients who have developed moist desquamation from radiation therapy. Therefore, the panel determined that silver sulfadiazine would serve as the standard of care for the following research question about treatment of radiodermatitis using dressings.

Should semipermeable dressings rather than standard of care be used to minimize the development of radiodermatitis?

Among individuals receiving radiation therapy, the ONS Guidelines panel suggests semipermeable dressings in addition to standard washing/skincare regimen rather than standard washing/skincare regimen alone to minimize the development of radiodermatitis (conditional recommendation; low certainty of evidence).

Summary of the Evidence

The systematic review (Ginex et al., 2020) identified eight studies that informed this question (Chan et al., 2019; Herst et al., 2014; Lam et al., 2019; Møller et al., 2018; Rades et al., 2019; Schmeel et al., 2018; Wooding et al., 2018; Zhong et al., 2013). Sample sizes ranged from 36 to 197. Interventions included Mepitel® film, StrataXRT®, hydrofilm, 3M™ Cavilon™ barrier film, and Mepilex® Lite. Comparisons were sorbolene, aqueous cream, and standard of care. Patient populations included patients with breast cancer or head and neck cancer. All but one study included prophylaxis application of semipermeable dressings from the start of radiation therapy.

The panel acknowledged that silver sulfadiazine is the current standard of care for patients who develop moist desquamation. One study was identified that reported on dressings for the treatment of moist desquamation and included a control group that received standard wound care with saline solution (Zhong et al., 2013). Because of the lack of evidence that compared dressings to silver sulfadiazine, the panel tabled the question of dressings for treatment of moist desquamation and will reconsider as new evidence becomes available.

Benefits

The use of dressings prophylactically resulted in a moderate reduction in the risk of the development of grade 2 or greater radiodermatitis (RR = 0.52, 95% CI [0.26, 1.03]; AAR = 224 fewer per 1,000, from 346 fewer to 14 more; low certainty of evidence); a moderate reduction in the development of moist desquamation (RR = 0.43, 95% CI [0.32, 0.58]; ARR = 205 fewer per 1,000, from 244 fewer to 151 fewer; low certainty of evidence); a moderate reduction in tenderness, discomfort, or pain (RR = 0.35, 95% CI [0.16, 0.78]; ARR = 167 fewer per 1,000, from 215 fewer to 56 fewer; low certainty of evidence); and a moderate reduction in pruritus (RR = 0.69, 95% CI [0.34, 1.38]; ARR = 64 fewer per 1,000, from 137 fewer to 79 more; very low certainty of evidence). Treatment of moist desquamation with semipermeable dressings may reduce the number of days until resolution of radiodermatitis compared to saline solution (mean difference = –7 days; 95% CI [–11.86, –2.14]; very low certainty of evidence); however, the estimate is likely uncertain when compared with the current standard of care of treatment with silver sulfadiazine.

Harms and Burdens

Mepitel film was not tolerated by patients in the study by Rades et al. (2019). At the time of a planned interim analysis, 13 of 28 patients (46%) did not tolerate the dressing, and the trial was stopped early. Reasons for not tolerating the dressing were discomfort/distress, feelings of tightness, and failure to properly adhere to the skin (Rades et al., 2019).

Certainty in the Evidence of Effects

The panel judged the certainty in the overall evidence of effects for prophylactic use of semipermeable dressings to be low because of concerns with risk of bias and imprecision. The panel judged the certainty in the overall evidence of effects for treatment of moist desquamation with semipermeable dressings to be very low because of concerns with risk of bias, indirectness of the comparison between saline solution to the current standard of care of silver sulfadiazine, and imprecision.

Other Evidence-to-Decision Criteria

The panel judged the desirable anticipated effects to be large for minimization and treatment with dressings and the undesirable anticipated effects for minimization and treatment to be small. The panel considered that there is probably no important uncertainty or variability in how much individuals value the main outcome of minimization of radiodermatitis. The panel judged that the balance of effects favors dressings for minimizing radiodermatitis. The costs would be large for dressings, with only one cost-effectiveness study, reported in a conference abstract, identified. Blades et al. (2019) analyzed the cost-effectiveness of StrataXRT and reported a 36% probability that StrataXRT would be cost-neutral or lead to a net savings for a healthcare institution. Equity would probably be reduced because of the cost of dressings. The panel judged that for minimization of radiodermatitis, acceptability among key stakeholders varies. Feasibility varies for the type of dressing used for minimization because of the experience and familiarity of the healthcare professionals and patients applying the dressings.

Conclusions

The panel acknowledged the large benefits of dressings and the small harms for minimization of radiodermatitis. Based on this evidence, the ONS Guidelines panel issued a conditional recommendation suggesting semipermeable dressings in addition to standard of care for the minimization of radiodermatitis.

Recommendation 8: Topical Steroid Creams

Should topical steroid creams rather than standard of care be used for the minimization or treatment of radiodermatitis?

Recommendation 8a (minimize development): Among individuals with cancer receiving radiation therapy, the ONS Guidelines panel suggests topical steroids in addition to standard washing/skincare regimen rather than standard washing/skincare regimen alone for the minimization of radiodermatitis (conditional recommendation; low certainly of evidence).

Remarks: Studies reported on topical steroid creams, both prescription and over the counter. If cost is a concern, the over-the-counter option is feasible. If coverage or availability is a concern, then available steroid cream is acceptable.

Recommendation 8b (treatment of symptoms): Among individuals with radiodermatitis symptoms (e.g., pain, itching), the ONS Guidelines panel suggests the addition of topical steroids to intact skin with a standard washing/skincare regimen rather than standard washing/skincare regimen alone (conditional recommendation; low certainty of evidence).

Remarks: Studies reported on topical steroid creams, both prescription and over the counter. If cost is a concern, the over-the-counter option is feasible. If coverage or availability is a concern, then available steroid cream is acceptable.

Summary of the Evidence

The systematic review (Ginex et al., 2020) identified six studies that informed this question (Hindley et al., 2014; Ho et al., 2018; Meghrahani et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2011; Ulff et al., 2013, 2017), all in patients with breast cancer. Sample sizes ranged from 50 to 202. Topical steroid creams included betamethasone (n = 2), mometasone (n = 3), and hydrocortisone (n = 1), with comparisons including moisturizing creams (n = 5) or diprobase (n = 1). The panel noted that topical steroids are only for intact skin and are contraindicated for areas of moist desquamation.

Benefits

Steroids may reduce the development of grade 2 or greater radiodermatitis (RR = 0.64, 95% CI [0.42, 0.96]; ARR = 224 fewer per 1,000, from 338 fewer to 57 fewer; moderate certainty of evidence) and on the development of moist desquamation (RR = 0.57, 95% CI [0.29, 1.12]; ARR = 161 fewer per 1,000, from 266 fewer to 45 more; low certainty of evidence). Steroids may result in a large reduction of pain during treatment (RR = 0.12, 95% CI [0.02, 0.98]; ARR = 62 fewer per 1,000, from 69 fewer to 1 fewer; low certainty of evidence) and pain after treatment (RR = 0.05, 95% CI [0.01, 0.39]; ARR = 178 fewer per 1,000, from 186 fewer to 114 fewer; moderate certainty of evidence).

Harms and Burdens

Steroid creams had a trivial risk of increased treatment-related adverse events (RR = 2.35, 95% CI [0.23, 24.26]; ARR 50 more per 1,000, from 29 fewer to 861; low certainty of evidence).

Certainty in the Evidence of Effects

The panel judged the certainty in the evidence of effects to be low because of inconsistency with data from blinding of outcome assessors and imprecision in that the confidence interval may not include meaningful data.

Other Evidence-to-Decision Criteria

The panel rated the desirable effects of steroid creams for minimization as large, considering the decreased risk of grade 2 or greater radiodermatitis and the desirable effects of treatment of symptoms as large, and considering the reduction in pain with trivial undesirable effects for minimization of radiodermatitis and treatment of symptoms. The panel considered that there was probably no important uncertainty or variability in how much individuals value the main outcomes and that the balance of effects for minimization of radiodermatitis and treatment of symptoms favors steroid cream. Moderate costs would be required for the steroid creams, and no cost-effectiveness studies were identified. The panel considered that there would probably be no impact on equity because steroid creams are accessible in most locations. The panel considered that steroids would be acceptable to key stakeholders but noted that steroid creams for minimization of radiodermatitis would be a change in practice in some centers. The panel judged that steroid creams would be feasible to implement.

Conclusions

The panel acknowledged the large benefits of topical steroids and the trivial harms for minimization of radiodermatitis and the treatment of symptoms. Based on this evidence, the ONS Guidelines panel issued a conditional recommendation suggesting topical steroid creams in addition to standard washing/skin care rather than standard washing/skin care alone for the minimization of radiodermatitis and topical steroid creams (on intact skin only) for the treatment of symptoms in patients with cancer receiving radiation therapy.

Discussion

Other Guidelines on Radiodermatitis

Evidence-based guidelines on the management of radiodermatitis in patients with cancer are limited. The guidelines were developed with different methodologies and at different times, so the evidence reviewed within each varies. The Society for Integrative Oncology (SIO) (Greenlee et al., 2017) includes recommendations in a guideline on integrative care during and after breast cancer treatment, and the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC) (Wong et al., 2013) published a guideline on the prevention and treatment of acute and late radiation therapy reactions from the MASCC Skin Toxicity Study Group.

The ONS Guidelines panel suggests the use of antiperspirant or deodorant or not, and the MASCC guideline recommends the use of antiperspirant during breast radiation therapy. The guidelines were consistent in not recommending the routine use of topical aloe vera for skin reactions from radiation therapy, with MASCC and SIO not recommending aloe vera and ONS recommending it only in the context of a clinical trial. Calendula was not recommended by MASCC or ONS for radiation therapy skin changes. MASCC and ONS suggest topical steroid creams for the minimization of radiodermatitis. A difference exists for treatment of radiodermatitis, with ONS recommending topical steroid creams and MASCC concluding that there was not sufficient evidence to support a recommendation for or against topical steroidal creams (Wong et al., 2013). The ONS Guidelines panel suggests semipermeable dressings for minimization of radiodermatitis, and the MASCC guideline (written several years prior) concluded that there was not sufficient evidence to support a recommendation for or against dressings (Wong et al., 2013).

Clinical Implications

Guidance is available on what should and should not be used to minimize the development and treat radiodermatitis during radiation therapy. Work needs to be done to change practice to include what evidence exists for and to eliminate practice that is not beneficial to patient outcomes. Although most patients who undergo radiation therapy experience some grade of radiodermatitis, the severity is known to vary based on a variety of patient- and treatment-related elements. Multiple skincare products have been examined, yet uncertainty remains by frontline clinicians on what should be used. Education of clinicians is critical to establishing care routines that promote patient self-care. Decision aids can enhance patient knowledge and understanding of their therapeutic options, as well as basic hygiene.

Conclusion

Future research priorities need to build on evidence-based interventions versus returning to products of the past that have not demonstrated efficacy. Well-designed studies with appropriate methodology and sample size are critical to moving this body of work forward. This is a critical juncture in the research, and products that address underlying mechanisms need to be selected (Chan, 2019). Standardized reporting tools and time points for assessment are critical because there is diversity in interpretation of the current tools, which makes comparisons across time points and studies difficult. Consistent product formulations are also important because it is a challenge to synthesize a wide variety of topical interventions. Patient-reported outcomes, including pruritus, pain, and other symptomology, are important to quantify, as well as cost impact to the patient and/or institution.

About the Author(s)

Tracy Gosselin, PhD, RN, AOCN®, NEA-BC, FAAN, is the chief nursing and patient care services officer at Duke University Hospital in Durham, NC; Pamela K. Ginex, EdD, RN, OCN®, is the senior manager of evidence-based practice and inquiry and Chelsea Backler, MSN, APRN, AGCNS-BC, AOCNS®, is an oncology clinical specialist, both at the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) in Pittsburgh, PA; Susan D. Bruce, MSN, RN, OCN®, AOCNS®, is a clinical nurse specialist at Duke Cancer Center Raleigh in North Carolina; Andrea Hutton is the director of content production and web publishing at PatientPower.info MBC Alliance in Santa Barbara, CA; Carol M. Marquez, MD, FACR, is a clinical associate professor in the Department of Radiation Oncology at Stanford University in San Jose, CA; Lisa A. McGee, MD, is a consultant at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, AZ; Anne Marie Shaftic, DNP, RN, AOCNP®, is an oncology nurse practitioner at New Jersey Cancer and Blood Specialists in Rutherford; Lauren V. Suarez, MSN, RN, OCN®, CBCN®, is a patient care manager at Miami Cancer Institute in Florida; Kerri A. Moriarty, MLS, is a research specialist and, at the time of this writing, Christine Maloney, BA, was an archivist and Mark Vrabel, MLS, AHIP, ELS, was an information resources supervisor, all at ONS; and Rebecca L. Morgan, PhD, MPH, is an assistant professor in the Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. The authors gratefully acknowledge the late Laura Curr Beamer, PhD, DNP, CNP, CNS, AOCNP®, AOCNS®, for her dedication, expertise, and scholarly work to improve the care of patients with cancer, particularly her work with patients receiving radiation therapy. Development of this guideline was wholly funded by ONS, a nonprofit nursing specialty organization that represents oncology nurses. ONS staff supported panel appointment and coordinated meetings but had no role in guideline question identification or voting on recommendations. Members of the guideline panel received travel reimbursement to attend one in-person meeting at ONS headquarters in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. No honoraria were provided. Mention of specific products and opinions related to those products do not indicate or imply endorsement by the Oncology Nursing Society. Gosselin, Ginex, Backler, Hutton, Marquez, McGee, Shaftic, and Morgan contributed to the conceptualization and design. Ginex, Backler, Bruce, Marquez, Shaftic, Moriarty, Maloney, Vrabel, and Morgan completed the data collection. Ginex and Morgan provided statistical support. Gosselin, Ginex, Backler, Hutton, Marquez, McGee, Suarez, and Morgan provided analysis. Gosselin, Ginex, Backler, Marquez, McGee, Shaftic, Vrabel, and Morgan contributed to the manuscript preparation. Ginex can be reached at pginex@ons.org, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted June 2020. Accepted June 24, 2020.)