Experiences of Turkish Parents of Hospitalized Children With Cancer During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study

Purpose: To describe the experiences of Turkish parents of hospitalized children with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants & Setting: Participants were recruited at the pediatric hematology-oncology clinic of a university hospital in Turkey. A purposive sampling strategy was used to identify participants. Parents who had a child aged 0–18 years with cancer were eligible.

Methodologic Approach: This study was conducted using a descriptive qualitative research design. Semistructured individual interviews with 14 parents of children with cancer were used for data collection. Data were analyzed using the content analysis method.

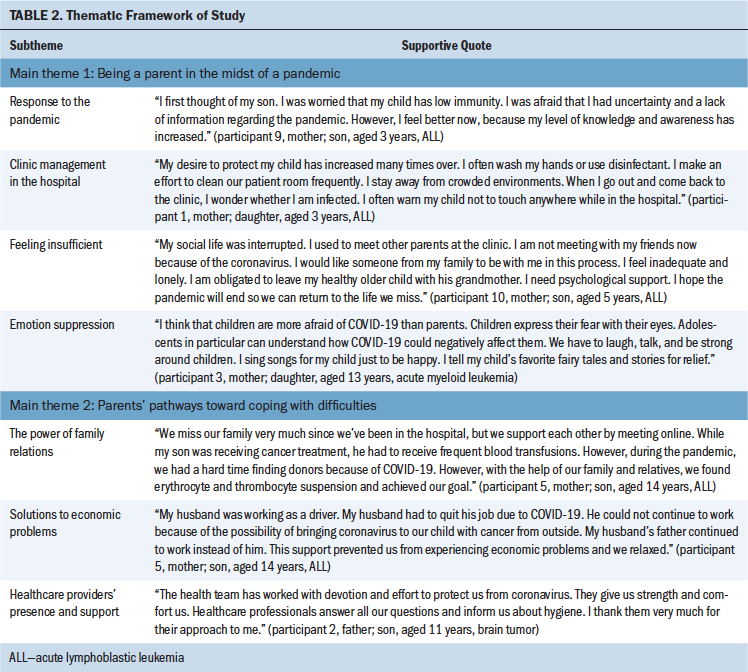

Findings: Two main themes with related subthemes were identified that revealed the lived experiences of parents of children with cancer: being a parent in the midst of a pandemic and parents’ pathways toward coping with difficulties.

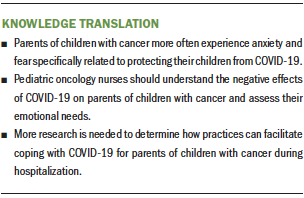

Implications for Nursing: Pediatric oncology nurses can develop clinical practices that help parents to cope with anxiety about COVID-19. Nurses should share with parents current and valid information about the child’s care during the pandemic. Future research should examine the experiences of children with cancer and their parents from different cultures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Jump to a section

The cancer treatment process is a substantial burden on children and their parents. In addition, parents suddenly had to face the reality of the COVID-19 pandemic while they attempted to cope with their children’s illness and treatment. Children receiving cancer treatment during the pandemic are at a disadvantage (Bouffet et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Unlike their healthy peers, for children with cancer, the pandemic can be life-threatening because of their vulnerability to infection caused by immunosuppression (Bouffet et al., 2020; Kaspers, 2020). In a study of 345 children confirmed to have COVID-19, one of the most common underlying conditions was immunosuppression (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 Response Team, 2020). Therefore, the COVID-19 outbreak causes parents great anxiety as they fear transmission of the virus. The COVID-19 pandemic also causes parents to be more careful as they try to protect their children from infection (Darlington et al., 2020).

Qualitative studies conducted before the pandemic determined that Turkish parents of children with cancer experienced sadness, anger, and depression (Demirtepe-Saygılı & Bozo, 2018; Günay & Özkan, 2019). Some published articles showed that the parents of children admitted to oncology clinics are prone to anxiety (Darlington et al., 2020; Salvador et al., 2020). Parents of children with cancer may be distressed more often now than before COVID-19. During the COVID-19 outbreak, the parents of hospitalized children with cancer may feel greater responsibility and fear than the general population, which may be because the pandemic threatens their children’s lives (Darlington et al., 2020).

Before the pandemic, mothers typically had to quit their jobs to care for their child with cancer, even if they highly valued their career (Kim et al., 2017). In addition, some families experienced unemployment and economic problems because of the pandemic. Low-income parents worried about the impact on childcare costs for their children (Nicola et al., 2020; Saab et al., 2020). In this context, pediatric oncology nurses should have the competence to support parents in a trustful relationship to develop coping strategies. A particular focus on life experience and coping resources should be a principle of nursing care (Enskär et al., 2020; Kaspers, 2020).

Considering the lack of knowledge about the experiences of Turkish parents of children with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic, this research aimed to describe the experiences of parents of hospitalized children with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of this study will help in planning additional studies using appropriate methods for parents of children with cancer. The research question was as follows: What are the experiences of Turkish parents of hospitalized children with cancer during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Methods

This study was conducted using a descriptive qualitative research approach (Streubert & Carpenter, 2011). The authors considered and followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research to improve the reporting quality of the study (Tong et al., 2007).

Participants and Setting

Study participants were recruited in person at the pediatric hematology-oncology clinic (PHOC) of Akdeniz University Hospital in Antalya, Turkey. The PHOC is a unit with 42 beds where pediatric patients aged 0–18 years receive cancer treatment. Only one parent or caregiver stays with each child in the clinic. A purposive sampling strategy was used to identify participants. Eligible parents were those who spoke Turkish, had a child with cancer aged 0–18 years, had stayed in the hospital for their child’s treatment during the pandemic, and had a child diagnosed with cancer more than two months prior. Two months postdiagnosis was chosen as a cutoff because, by that point, parents have completed the process of accepting the diagnosis and are better able to communicate and express themselves.

To gain an extensive overview and rich descriptions of parenting experiences, this study did not impose a specific diagnosis for the children, and children aged 0–18 years were included. Data saturation was the basis for determining the appropriate sample size (Morse, 2015). Twenty-four parents were assessed for study participation. Eight mothers did not agree to participate (because they did not want to share their personal experiences), and two mothers were excluded because their children were newly diagnosed. After 14 interviews, the researchers assumed that data saturation was achieved because no new information was obtained in the interviews. Fourteen participants (12 mothers and 2 fathers) were eventually recruited for the study. Most participants were women because, in the traditional social structure of Turkish culture, fathers pass care responsibility for their children to mothers, and mothers usually stay with their children in the hospital (Demirtepe-Saygılı & Bozo, 2018).

Data Collection

The study used a qualitative approach. Study data were obtained during August and September 2020 from parents of children with cancer hospitalized during the COVID-19 pandemic. An interview guide and a personal information form (including demographic characteristics of parents and their children with cancer) were used. Data were collected with semistructured interviews and researcher observations. The individual in-depth interview method was used to gain detailed knowledge of parents’ subjective emotions, thoughts, and experiences (Streubert & Carpenter, 2011). Each interview was conducted by the second author (T.Ç.), a female pediatric nurse with a master’s degree. One face-to-face interview was arranged with each parent who had agreed to participate. Interviews were carried out at a time that was convenient for parents in a private room in the PHOC that was quiet and free of stimuli. Research data were obtained from participants with whom the researchers had no previous relationship.

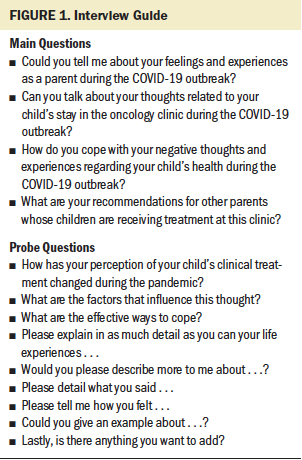

Semistructured Interview

During the interviews, the researchers used a semi-structured interview guide that included four open-ended qualitative items (see Figure 1). The qualitative questionnaire was created in light of the literature review and the academic and clinical experience of the researchers. Potential sources of bias from the research team in the interview guide were minimized by having an expert in the field of nursing evaluate the meaning, purpose, and scope of all interview questions. Prior to the interview, the second author informed the participants about the goals and reasons for doing the research. The parents were supported and encouraged to speak freely. The perspectives and life experiences of the parents regarding the COVID-19 outbreak were clarified during the in-depth interviews. Each interview lasted about 15–30 minutes and was conducted face-to-face with the parents. Both the researcher and the parents used masks, and social distance was maintained to minimize the risk of spreading COVID-19.

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethical Committee. The parents were informed that their identity and the audio recordings would remain confidential and that their experiences would only be used for scientific purposes. They were also informed that they had the right to withdraw from the research at any time. Parents volunteered to participate in the study. Written and verbal consent was collected.

Data Analysis

The interviews were recorded using a digital audio recorder and were transcribed verbatim. M.G. compared all written transcripts to original audio recordings. Data translations were directed by a pediatric oncology nurse who was an expert in pediatric nursing and qualitative research. An independent translator conducted the data translation process from Turkish into English. Three Turkish-speaking researchers compared Turkish and English versions to determine whether the transcripts were appropriate and correct in English. The transcribed data were analyzed using the content analysis method. The data analysis was conducted during September and October 2020.

Three researchers (M.G., T.Ç., and S.A.T.) contributed to the data analysis phases to enhance internal validity. Prior to data analysis, data coders identified and discussed personal prejudices, assumptions, experiences, and any biases that may affect analysis. Because researchers’ prior knowledge, beliefs, and assumptions can influence the themes identified, researchers must put them aside to enhance credibility (Creswell & Creswell, 2017).

The researchers individually read the entire text of the interviews and listened to recordings repeatedly without criticism or bias to obtain a general impression. The researchers made an effort to look for themes that reflected parents’ thoughts and experiences regarding COVID-19. The underlying meanings of the interviews were reviewed and interpreted. The materials were compared to identify content associations, similarities, and differences. The meaning units were condensed, abstracted, and coded. First, the researchers coded the contents of the interviews separately. Then, the researchers met regularly to discuss their coding consistency and to reach consensus. A code list was created. If two different themes were identified by researchers, these were combined into a single theme. Finally, the study findings were formulated into two themes and associated subthemes (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004; Vaismoradi & Snelgrove, 2019).

Rigor and Trustworthiness

The second author (T.Ç.) conducted all the semistructured interviews to enhance the rigor in this research. Some measures to enhance rigor and trustworthiness included direct quotations from the interviews being transcribed verbatim, prolonged engagement with transcripts, and careful and deep review and checking of qualitative data for analysis. To improve trustworthiness of the findings, the third author (S.A.T.) participated in all data analysis discussions, and member checks were conducted on all transcripts (Creswell & Creswell, 2017). In addition, every effort was made to synthesize the themes most representative of the data to strengthen accuracy and credibility. The data analysis and quotations from different parents were described to enhance confirmability. The selection criteria and characteristics of the participants and the data collection and analysis phase of the study were explained clearly to facilitate transferability. Lastly, the qualitative study data were documented to enable future audits (Connelly, 2016; Graneheim & Lundman, 2004).

Findings

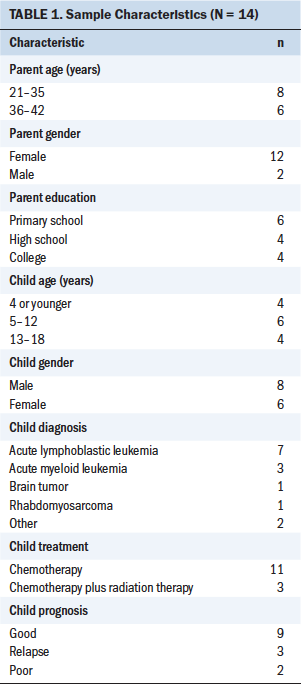

The mean age of the parents was 32.92 years (SD = 6.3), and the mean age of their children was 8.42 years (SD = 5.01). The demographic data of the parents and their children are shown in Table 1. The qualitative data were synthesized into two main themes and associated subthemes (see Table 2).

Being a Parent in the Midst of a Pandemic

The first main theme consists of the following four subthemes: response to the pandemic, clinic management in the hospital, feeling insufficient, and emotion suppression.

Response to the pandemic: Most participants stated that when they first learned about the pandemic, they were shocked and worried for their children with cancer. The parents did not want to expose their children, who were already fighting cancer, to COVID-19. Parents’ fear of infection caused them to feel panic and anxiety. They emphasized that they paid extra attention to avoiding COVID-19 by washing their hands, cleaning the patient’s room, changing their clothes constantly, and not meeting other parents.

Nobody is more important to me than my children. I always live in fear of any harm to my children. I’m always praying for them. My child with cancer already has a life full of limitations due to disease. I always wash items from outside, such as food and toys, before giving them to my child. I don’t want my husband to touch, hug, and kiss my child because he is not staying at the clinic. I am very scared of my child getting infected. I feel like I always have to be with my daughter. (participant 3, mother; daughter, aged 13 years, acute myeloid leukemia [AML])

Clinic management in the hospital: Many of the parents emphasized that they felt relaxed in the hospital and expressed that their children were safer in the clinic than outside. Parents pointed out that they trusted healthcare providers because they pay so much attention to COVID-19 safety protocols. They also highlighted their satisfaction with the protective practices in the clinic.

At first, we did not want to come to the hospital. We were worried that our child would get coronavirus while receiving treatment at the hospital. However, the precautions taken by the health teams while in the hospital satisfied us. A lot of attention is paid to cleanliness. Service is provided in a hygienic environment, and I think the team approach to COVID-19 management is very successful. All rooms have disinfectant. Healthcare professionals are making an effort here. Therefore, I was relieved after our hospitalization. (participant 2, father; son, aged 11 years, brain tumor)

Feeling insufficient: Several parents pointed out that when their children with cancer are discharged, healthy siblings have to go and live with their grandparents. Participants emphasized that they felt they were inadequate parents to their healthy children because of the obligation to protect their sick children. Some parents also stated that they maintain social distance to protect their children; they make an effort not to hug or kiss their children. They stated that these conditions result in sadness and strain for parents and children.

I have two kids. When my healthy child comes to visit the hospital, I see him outside. I cannot hug my healthy child. My child with cancer in the hospital wants to sleep next to me and hug me; she says that she misses me even though we’re in the same room. As a mother, I cannot touch, hug, or kiss my child even though I’m near her. If I get coronavirus, I could infect my daughter. Since she has cancer, I have to make her feel my love. It is a very difficult situation. I feel very sad; I feel insufficient. (participant 3, mother; daughter, aged 13 years, AML)

Emotion suppression: Most parents underlined their children’s understanding of the risk of COVID-19 and fear of dying. They emphasized that they try to hide their negative emotions from their children. The parents felt that they have a significant effect on their children’s emotional and mental health.

My son and I do not leave the room at the hospital due to the COVID-19 risk. We are overwhelmed and bored, but I’m trying not to show this to my son. I advise other parents not to be angry or upset with their children, because children feel when we get pessimistic. Other parents should never stop loving and showing interest in their children, and they should be psychologically supported. (participant 4, mother; son, aged 17 years, AML)

Parents’ Pathways Toward Coping With Difficulties

The second main theme consists of the following three subthemes: the power of family relations, solutions to economic problems, and healthcare providers’ presence and support.

The power of family relations: Parents emphasized the importance of family support to be strong and overcome difficulties. It was all about being positive and transferring family members’ love to each other.

My wife and I overcome the difficulties by supporting each other. When my wife asks how my child is on the phone, I respond positively that he is very good, even if he is not. My wife also gives me such motivation. Thus, our child is also positively affected. I recommend that other parents trust their family and tell their children that they will overcome these difficulties and that they are stronger than cancer and coronavirus. (participant 2, father; son, aged 11 years, brain tumor)

Solutions to economic problems: Many participants stated that at least one family member was unemployed and exposed to economic problems because of the pandemic. Parents stated that they feel very upset and worried when they cannot buy what their children need.

My husband was unemployed due to the pandemic. We are already in a difficult period due to cancer. In this process, I was very afraid of what we would do, how we would succeed. However, our relatives, friends, and teachers at my daughter’s school often called us. They collected money at the school and gave it to us. I was very touched by this and very happy. In this way, we did not experience financial difficulties. Now, we are shopping online for my daughter on the spot. My daughter is happy with this support, clinging to life. (participant 3, mother; daughter, aged 13 years, AML)

Healthcare providers’ presence and support: All the parents stated that they were satisfied with the support provided by healthcare providers. Parents emphasized that they mostly share their feelings and thoughts with healthcare providers because these were the only people they spoke to face-to-face during the pandemic.

All the nurses and doctors are doing their best to help my child recover and protect him from coronavirus. My hope is God first, then healthcare professionals. I trust them; I feel safe. Nurses never speak loudly to us. I am very glad that they are friendly, good, and sweet. I have never experienced any negative behavior. So, I’m very happy. (participant 5, mother; son, aged 14 years, acute lymphoblastic leukemia)

Discussion

This study aimed to describe Turkish parents’ experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic during their PHOC stay. In this study, the experiences of parents of children with cancer during the pandemic were investigated in-depth for the first time in Turkey. All the parents stated that healthcare providers have been successful in COVID-19 prevention and clinical management. In addition, most parents felt that the hospital was a safe place for their children because healthcare providers are very rigorous and follow standard precautions. This finding is not consistent with Darlington et al. (2020), who determined that the hospital was no longer considered a safe place for most parents of children with cancer. The reason for this difference in parents’ perspective may be differing healthcare conditions or cultural factors in hospitals, or the approach of healthcare providers.

The current study demonstrated that all the parents experienced fear of transmitting COVID-19 to their children with cancer because they did not want to lose their children. In addition, a negative prognosis for children with cancer was related to greater fear. However, there was no distinctive difference in parents’ fear according to children’s ages. This view is supported by some previous studies (Darlington et al., 2020; Saab et al., 2020). In addition, in the current study, the parents highlighted that children with cancer are in a vulnerable position and that parents must be ready to protect them from almost anything. One of the most noteworthy findings of this study was that children with cancer miss their mothers even when they are around. Although children with cancer need love more than ever, parents tried not to hug and kiss them because of fear of transmitting the virus. In addition, healthy siblings had to stay away from home to protect the children with cancer from COVID-19 after they were discharged, which disturbed parents’ consciences. Some parents faced obstacles during their struggle with COVID-19 and felt insufficient as parents in caring for their children. The research team realized that parents needed strengthening interventions that would increase their self-confidence.

Another finding of the current study is that parents stay away from other parents of children with cancer in the hospital because of fear of COVID-19. The parents stated that they had to maintain social isolation to protect their children. The finding that parents and their children are more isolated than before the pandemic is supported by a previous study (Darlington et al., 2020). Some previous studies conducted before the pandemic reported that the support from other parents of children with cancer was perceived as a tool to facilitate coping with the process (Beddard et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2017). This lack of social support is a major loss and challenge for parents. It is important for healthcare providers to be aware of this need of parents and focus on this issue.

Parents in the current study mentioned that hiding their negative emotions from their children was fundamental. According to the findings, parents of adolescents made more efforts than parents of young children to suppress their sadness and fear because adolescents in particular can understand how COVID-19 could negatively affect them. This finding is supported by a previous study conducted with parents of children with cancer in Turkey (Demirtepe-Saygılı & Bozo, 2018). Another study identified the desire to protect their children with cancer as the main obstacle preventing Korean parents from sharing their feelings (Son et al., 2020). The findings of the current study are consistent with existing research results, despite cultural differences. Emotional suppression decreases individuals’ sense of authenticity because it prevents them from showing the emotions they actually feel (English et al., 2013). The suppression of negative emotions is an unhealthy emotion regulation method that can result in depressive symptoms (Le & Impett, 2016). Parents of children with cancer who express their emotions experience relief and improved well-being (Duncan et al., 2007). For this reason, considering the negative effects of suppressing emotions, pediatric oncology nurses should find varied ways to help parents express their emotions, such as by participating in art therapy activities (Gürcan & Atay Turan, 2020; Jiang et al., 2020).

A determining theme during the interviews was the parents’ pathways toward coping with difficulties. In this study, the support of family and healthcare providers was at the forefront of parents coping with challenges during the pandemic. The parents in this study strongly believed that children with cancer and their parents could cope with difficulties through love and commitment within the family. Similarly, a previous study indicated that feeling family togetherness relieved the parents (Ångström-Brännström et al., 2010; Günay & Özkan, 2019). In Turkish culture, familial relationships are very strong. The reason for the effectiveness of family support may be that parents expect love and effort from those they have the closest relationship with during their toughest times.

The predominant message from the majority of parents was that the presence and support of healthcare providers is important during the pandemic. This knowledge is supported by several other studies (Darlington et al., 2020; Zucchetti et al., 2020). Pediatric oncology nurses should be aware of the importance and power of their position for parents and their children. In addition, nurses should pay more attention to understanding parents’ experiences during the pandemic and evaluating their psychological needs to enhance their psychological health.

Limitations

There were potential limitations to this research. First, the parents were recruited from one clinic. Second, parents may have different experiences because their children had various diagnosis periods and ranged in age from 0 to 18 years. Third, it is possible that including more male parents in this study may have revealed additional findings. Fourth, assessing participants’ emotions was difficult when wearing masks during interviews. Future studies should consider these limitations.

Implications for Nursing

In light of the results of the current study, pediatric oncology nurses can develop clinical practices that help parents to cope with their care burden. In addition, nurses should listen to parents and share with them current and valid information about the child’s care during the pandemic. If parents have incorrect information, nurses should correct and update them. Improved supportive care environments are required to enable parents to make meaningful choices about COVID-19 management and to support their autonomy in informed caring for their children with cancer. Healthcare providers and parents should work in partnership to maintain and promote children’s health during the PHOC stay (Sullivan et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Institutions that parents can refer to for financial problems can be suggested. Future research should examine the experiences of children with cancer and their parents from different cultures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

This qualitative research has provided important insight into Turkish parents’ experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic during a PHOC stay. This study showed that the COVID-19 pandemic has negative effects on the ability of parents of children with cancer to feel sufficient to care for their children and to cope with the cancer treatment process. Parents and their children with cancer are more isolated than before the pandemic. Participants suppressed their negative emotions to protect their children from psychological harm. When pediatric oncology nurses performed care tasks skillfully, parents trusted them and felt that their children were safe. Pediatric nurses should adopt a holistic vision of care and focus on the emotional dimension. Handled correctly, the hospitalization process could help parents to be satisfied with nursing care, cope effectively, gain strength, and acquire self-confidence.

About the Author(s)

Meltem Gürcan, MSc, RN, is a research assistant in the Faculty of Nursing at Akdeniz University, Tuğba Çelebi, RN, is a pediatric oncology nurse at Akdeniz University Hospital, and Sevcan Atay Turan, PhD, RN, is an assistant professor at Akdeniz University, all in Antalya, Turkey. No financial relationships to disclose. Gürcan and Atay Turan contributed to the conceptualization, design, and manuscript preparation, and provided statistical support. All authors completed the data collection and provided analysis. Gürcan can be reached at meltemgurcan@akdeniz.edu.tr, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted November 2020. Accepted January 12, 2021.)