Experiences of Muslim Cancer Survivors Living in the United States

Purpose: To gain an understanding of the cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship experiences of adult Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States.

Participants & Setting: A purposive sample of 17 male and 15 female Muslim cancer survivors was recruited from across the United States. Data on Muslim cancer survivors’ experience were collected through individual, in-depth, semistructured interviews.

Methodologic Approach: An interpretive, descriptive, qualitative approach was used to gain an understanding of the experience of Muslim cancer survivors.

Findings: Six broad themes were identified to gain an understanding of the cancer experiences of adult Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States: (a) cancer experience based on their belief in God, (b) hiding cancer diagnosis, (c) perceived strong social support, (d) making an effort to keep up with religious practices, (e) perceived discrimination in healthcare settings, and (f) importance of religion and cultural awareness.

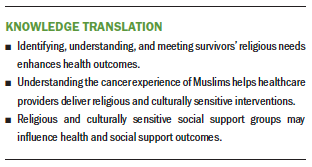

Implications for Nursing: This study provided key information concerning the unique experience of Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States. Identifying, understanding, and meeting survivors’ religious needs, as well as understanding their cancer experience, may reduce cancer health disparities and enhance health outcomes.

Jump to a section

Muslims represent a large, rapidly growing segment of the population in many Western countries, including the United States. About 3.45 to 7 million Muslims reside in the United States (Mohamed, 2018; Padela & Curlin, 2013). By 2050, it is estimated that the Muslim population will reach about 8.1 million individuals (Mohamed, 2018). Therefore, health professionals in the United States will provide care to an increasing number of Muslim cancer survivors with distinct and unrecognized healthcare needs and outcomes related to their religious beliefs and cultural values.

Background

The religion of Islam affects all aspects of a Muslim’s life, including thoughts and behaviors regarding health, illness, and death (Wehbe-Alamah, 2008). Muslims believe that illness or wellness is God’s will (Wehbe-Alamah, 2008; Zahr & Hattar-Pollara, 1998), and they receive illness and death with patience and prayers (Sirois et al., 2013; Wehbe-Alamah, 2008). The family system for most Muslims in Islamic countries is dominated by an extended structure (Daneshpour, 1998; Weatherhead & Daiches, 2010). According to Islam, it is important to visit someone who is ill in the hospital and/or at home (Padela, Killawi, et al., 2012; Wehbe-Alamah, 2008) and to make supplication for the sick (Padela, Killawi, et al., 2012). In supplication, a person can ask at any time for help and directions through private and humble conversation with the one who owns and creates everything (Kabbani, 2007). The religion of Islam and the nature of the family shape Muslims’ beliefs and consequently may influence the way Muslim cancer survivors deal with their survivorship experience.

Cancer survivors experience physical, emotional, psychological, and social difficulties from cancer diagnosis and treatment (de Moor et al., 2013; Frenkel et al., 2015). These difficulties include fatigue, pain, fear of recurrence, fear of developing secondary cancers, fear of death, financial difficulties, other comorbid conditions, and economic burdens (Aaronson et al., 2014; de Moor et al., 2013). Collaborative efforts are needed from researchers and clinicians to address the diverse needs of cancer survivors across all stages of survivorship (Aaronson et al., 2014; Alfano et al., 2014; de Moor et al., 2013).

Prior studies of Muslim cancer survivors were primarily conducted in Islamic countries, and several of these studies demonstrated the impact of religion on their cancer experience. (Alaloul et al., 2016; Errihani et al., 2008; Jazieh et al., 2012; Zeeneldin & Taha, 2012). For example, in a qualitative study, Alaloul et al. (2016) aimed to understand spirituality among Arab Muslim survivors. Findings showed that religious activities helped Arab Muslim cancer survivors living in Jordan cope with their cancer experiences. In a cross-sectional comparative study, Alaloul et al. (2015) examined differences in health-related quality of life among 63 cancer survivors and a healthy matched comparison group. They found no significant difference in emotional functioning between the two groups. This may be because of the protective influence of Islamic beliefs on coping with illness (Alaloul et al., 2015). Errihani et al. (2008) studied the impact of cancer on 1,600 Muslim cancer survivors in Morocco. They found that most cancer survivors were more adherent to their religious practices after the cancer diagnosis. In reviewing the literature regarding the experiences of women with breast cancer in Middle Eastern countries, Fearon et al. (2020) concluded that these experiences are influenced by community views of cancer, the role of women in family and society, and religion. Previous studies on Muslim cancer survivors in Islamic countries mainly include one ethnic subgroup of the Muslim population and lack exploration of the differences in the cancer experiences across ethnic backgrounds. The Muslim population has a variety of ethnic backgrounds. Studies conducted in Islamic countries highlight religious and cultural influences on Muslims’ health behaviors toward their cancer experience and involvement with health care.

Despite the growth in research addressing the impact of cancer on the lives of survivors, there is very limited research regarding the cancer experiences of Muslim survivors residing in the United States and the impact on their potentially unique needs (Obeidat et al., 2012). Lack of understanding of their experience within the context of religion can create barriers, such as mistrust, misunderstanding, stigmatization, perceived discrimination, and impaired communication (Padela & Curlin, 2013; Padela, Gunter, et al., 2012; Silbermann & Hassan, 2011; Wehbe-Alamah, 2008). These barriers may increase healthcare disparities (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2010; Padela, Gunter, et al., 2012; Padela, Killawi, et al., 2012) and negatively affect healthcare outcomes and survivors’ satisfaction with health care (Inhorn & Serour, 2011; Kagawa-Singer et al., 2010; Sirois et al., 2013).

Theoretical Framework

The conceptual framework of the study is Leininger’s theory of culture care diversity and universality (Leininger, 1988, 1991). This framework focuses on the importance of providing culturally sensitive care for individuals, families, groups, and communities to improve their health and well-being and help them manage illness, disability, or death. To provide culturally sensitive care, nurses need to be aware of others’ values, beliefs, and practices and apply this awareness appropriately to their nursing care. Several factors, including religion, politics, and socioeconomic status, can influence cultural care (Leininger, 1991). The purpose of this study is to gain an understanding of the cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship experiences of adult Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States.

Methods

An interpretive, descriptive, qualitative approach was used to gain an understanding of the experiences of Muslim cancer survivors from their perspectives and within the context of their culture (Thorne, 2016; Thorne et al., 1997). Data on Muslim cancer survivors’ experience were collected through individual, in-depth, semistructured interviews. A follow-up interview was conducted with a subsample of participants to validate findings. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Louisville in Kentucky.

Sample and Settings

A purposive sample of 17 male and 15 female Muslim cancer survivors was recruited from across the United States. Participants were recruited from the western, southern, northeastern, and midwestern United States. Participants were included if they were aged 18 years or older; self-identified as Muslim; spoke and read either Arabic, English, or Urdu (major language of South Asians); and self-identified as being one to six years post–cancer diagnosis. The National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship (2014) defines cancer survivorship from diagnosis onward. A five-year postdiagnosis period was chosen to minimize recall bias in capturing the experience of cancer diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship. Exclusion criteria were individuals diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma who received minor treatment and current hospitalization.

Four approaches were used to recruit study participants: (a) posting flyers in oncology offices and areas frequented by Muslims, (b) speaking to Muslim religious leaders and physicians, (c) snowball sampling, and (d) social media (e.g., Facebook®) with a secure website link. The first author of the current article, who is Muslim, met with female and male community leaders and two Muslim oncology physicians to discuss the study and solicit their suggestions and support for recruitment of study participants (Alaloul et al., 2019).

Instruments

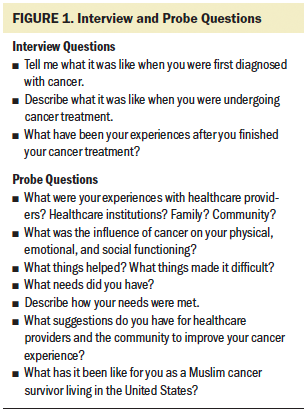

A semistructured interview guide with open-ended questions was used to explore the experiences of Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States. Specific questions were asked related to their general experiences across all stages of survivorship, interaction with the healthcare system, and the influence of their Islamic religious beliefs and cultural values, as well as their unique religious and cultural needs (see Figure 1).

The interview guide was developed based on the first author’s clinical experience with cancer survivors, including Muslim cancer survivors, and a review of the literature on survivors’ cancer experiences (Burg et al., 2015; Errihani et al., 2008; Obeidat et al., 2012; Schulz et al., 2008). Interview questions were evaluated and modified by the research team, who have extensive experience in the field of psychosocial oncology and qualitative research. Finally, interview questions were assessed and confirmed by a Muslim medical oncologist and two Muslim non–healthcare providers. Interviewers used probes to increase clarity and depth of content and to identify feelings. A demographic and medical form was used to collect participants’ age, sex, marital status, level of education, race, employment status, cancer type, time since diagnosis, and treatments received.

Data Collection

The study was explained to interested potential participants, and participants were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria. Once interest and eligibility were established, an interview time, place, and method (i.e., in-person or telephone) was determined. The Leininger’s theory of culture care diversity enhanced cultural sensitivity throughout the interview process. Interviews were conducted by research team members (male and female) fluent in Arabic, English, and/or Urdu in the language preferred by the participant. For some Muslim survivors, it was necessary to ensure an interviewer of the same sex. To verify data and validate findings, a follow-up interview was conducted with three male and three female survivors. During the second interview, participants were invited to comment on and clarify initial study findings. Both interviews were digitally audio recorded with the participant’s permission. Participants were compensated with a non-monetary gift valued at $25 (e.g., thermal coffee carafe, coffee mug).

Data Management

Most of the interviews were conducted in English. Interviews conducted in English were transcribed by the research assistants. Interviews conducted in Urdu and Arabic were translated into English and transcribed by the research assistants immediately after each interview. To ensure appropriate transcription and translation, the first author, who is fluent in English and Arabic, and a team member, who is fluent in English and Urdu, reviewed the recorded interviews and the English-translated transcripts. Any disagreements after the verification process were discussed until consensus was reached. Once validated, transcripts were uploaded to Dedoose qualitative software, version 6.1.18, for data management and analysis. Data were organized by individual interview and each participant’s responses to each interview question. Initial data analysis began immediately after the first interview, which guided and enhanced data collection for the subsequent interviews (Sandelowski, 1995). Confidentiality was maintained by removing any identifiers (e.g., name, place of worship).

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Inductive thematic analysis was used to identify themes related to Muslim cancer survivors’ experience (Braun & Clarke, 2006). The approach of Braun and Clarke (2006) was used to analyze interview data to develop a beginning understanding of the experience of Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States. This approach was employed in a previous study conducted with Arab cancer survivors residing in Jordan (Alaloul et al., 2016). Thematic analysis steps of Braun and Clarke (2006) consist of data familiarization, generation of initial codes, search for general themes, revising themes, naming themes, and report production. The research team was flexible and iterative in applying these steps.

Familiarization with data began during the data collection and data validation processes. During the validation process, researchers identified expressions and ideas that guided them in the subsequent data analysis process. Research team members actively read the transcripts to grasp the overall meaning of each interview before identifying initial codes.

For generation of initial codes, team members identified and listed initial codes independently by reading the transcript line by line while being aware of the participant’s responses to each interview question and the overall meaning of each interview (Sandelowski, 1995). All codes were reviewed until consensus was reached to ensure coding accuracy. After identifying initial codes, team members independently matched codes with data extracts. Codes were sorted and classified into general themes based on the study purpose. Team members organized all coded data extracts under each identified relevant theme.

Themes were reviewed, discussed, and verified by the research team members to enhance credibility. They evaluated the consistency of all coded data extracts with relevant themes. To have distinct and meaningful themes, the researchers modified, collapsed into another theme, deleted, or categorized initial themes into separate themes and subthemes. Identified and accepted themes and subthemes were then defined and named. Research team members used these identified themes to grasp the meaning of each interview before making comparisons across interviews (Sandelowski, 1995). The analysis process aimed to move beyond the description of themes to define the connections between these themes. Understanding the meaning of each theme and how themes relate to each other, as well as the general sense of the whole interview, aided in understanding the overall experiences of Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States.

Findings

Thirty-seven participants were screened for inclusion and exclusion criteria, and only one participant did not meet the eligibility requirements. Thirty-six participants were invited to participate; four individuals did not respond to the invitation. Speaking to Muslim community leaders and using social media were the most effective strategies in recruiting Muslim cancer survivors; using social media enhanced recruitment from across the United States.

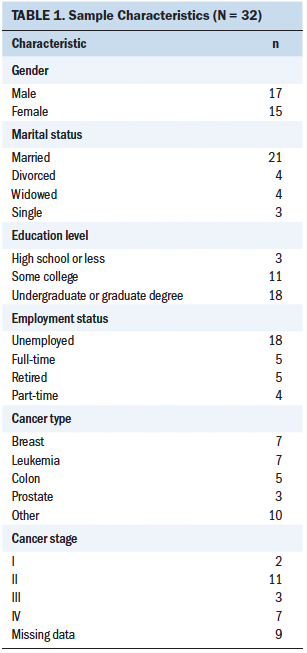

Thirty-two Muslim cancer survivors participated in the semistructured interviews. The characteristics of the 32 participants are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 56.3 years (range = 24–83 years). The mean number of years post–cancer diagnosis was 3.4 (SD = 1.6). Most participants received more than one cancer treatment (e.g., chemotherapy, surgery, hormonal).

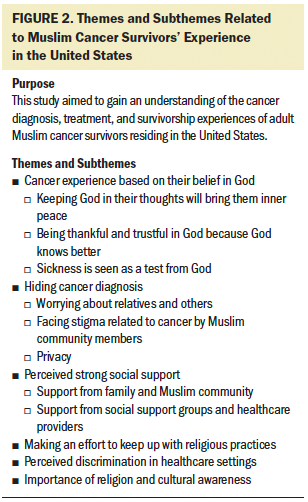

The purpose of this study was to gain an understanding of the cancer experiences of adult Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States. Six broad themes were identified: (a) cancer experience based on their belief in God, (b) hiding cancer diagnosis, (c) perceived strong social support, (d) making an effort to keep up with religious practices, (e) perceived discrimination in healthcare settings, and (f) importance of religion and cultural awareness (see Figure 2).

Cancer Experience Based on Their Belief in God

Most Muslim cancer survivors included in this study viewed their cancer experience through their belief in God. Most participants believed that their strong connection with God could cure their disease and help them cope with the negative aspects of their cancer experience. Cancer experience based on their belief in God was viewed in three ways: (a) keeping God in their thoughts will bring them inner peace, (b) being thankful and trustful in God because God knows better, and (c) sickness is seen as a test from God.

Keeping God in their thoughts will bring them inner peace: A majority of participants believed that being close to God and keeping him in their thoughts will bring peace to their minds. As illustrated in the following quotes, participants voiced that being close to God can help people during illness and protect them.

I appreciate having the time with God one to one. This helps me get things right. I did a lot of prayers and a lot of reliance on Allah [God]. It did help a whole lot. It helps me to be with Allah. (participant 16)

The only thing that came to my mind is that feeling I had these wings wrapped around me, this warm peaceful feeling, and I did not even know the words that were going to come out of my mouth until they did. I think this peaceful feeling came from Allah [God]. God has guided me through all of this. (participant 7)

I became closer and closer to Allah [God], to my Creator, in my illness. (participant 3)

Being thankful and trustful in God because God knows better: Many participants’ statements showed their acceptance of God’s will and their trust in his support. They believe that God is aware of all things and that he knows what is best for them. They believe that God decrees sickness for a reason. Therefore, accepting God’s will, by being thankful and trustful in God, will be rewarded either in life or in the hereafter.

As a Muslim, I have faith in God. I believe that my age is predetermined. I have to be thankful. I leave it to God. (participant 12)

I believe that whatever happens will be from Allah [God], and it will be good. (participant 2)

If Allah [God] wants this thing to happen, then there is a reason for that. It does not mean that to get negative with our belief, with our religion. As a Muslim, it means that you accept it even it is a negative thing. It is the will of Allah; this was really the source of my support. (participant 24)

To accept it, to know that whichever way the Creator sees it that’s from him—it is not from the people, it is not from the doctor—it is from the Creator, whatever he wants. (participant 19)

Sickness is seen as a test from God: Many survivors viewed their sickness as a test from God. God tested them with hardship and difficulties to see if they succeed in their tests to receive his rewards in life and hereafter. Specific statements illustrating this theme included the following:

I considered it the expiation of sins. . . . I considered it a way to get to a higher degree. . . . God is the Creator. God placed me in this test to know if I accept it and to be patient. (participant 20)

It is a test for me. I look at it from the Islamic perspective, and every hardship is a test. Sometimes, it is a benefit, but we do not know the benefit until we go through it. (participant 4)

This is just the test of this world, that God showed me, and I thank God whatever he gives me. And I say this is to make me remember him too much, so I say it is OK. I do not have to think about it; I have to take life easily. (participant 28)

Hiding Cancer Diagnosis

Many survivors stated that they hid their cancer diagnosis and suffering from others. Reasons voiced for hiding their cancer diagnosis were categorized into three subthemes: (a) worrying about relatives and others, (b) facing stigma related to cancer by Muslim community members, and (c) privacy.

Worrying about relatives and others: Many participants stated their concerns about others’ feelings. They were trying to hide their cancer diagnosis and suffering from their relatives and loved ones to avoid hurting their feelings. They did not want close relatives to suffer, particularly those who lived overseas.

I could not do the same thing with my family or friends. I kept sad part of it, kind of out. I could not be open with them about that. I think that made it difficult, just because they have never got the full idea, how much things have gotten bad to me. I kept that away from them, and I hid a lot from them. So, to them, I would only show the positive side of me, a big smile and be happy, and I kept a lot of personal things from them. (participant 26)

Because my parents are still alive, and they are living in [country of origin], I did not want the [cancer diagnosis] to travel to them, but rather me, hoping to get better to travel back to [country of origin] and sharing my health status with them directly. So that I can protect my aging parents from the shock of hearing something like that from a distance. (participant 14)

We did not want my family to notice right away. We hid it from my parents and other brothers and sisters. We told them that there was something wrong with me, and I have to stay at the hospital for one night. (participant 18)

If I go to radiation, it might affect my family; radiation might negatively affect them. I was thinking of my family too. But they told me that it might not affect them. (participant 32)

Facing stigma related to cancer by Muslim community members: Several participants were concerned about the way that Muslim community members, including relatives, dealt with cancer survivors and their views toward cancer. They indicated that some community members were not aware of how to deal with cancer survivors appropriately. Participants voiced feeling alienated by hurtful comments, reactions, and looks of pity from Muslim community members. Many survivors hid their cancer diagnosis to avoid these negative experiences.

I feel that the older generation would look at me like I was still broken, or there is still some chance that I will get sick again. So, that’s always on their mind, every time they see me or talk to me, “Oh, how is your health? Do you feel sick?” They still focus on that part. Even though I have moved forward, and I am doing much better, they still look at me that I am still sick or in the same situation. (participant 26)

I was lying on the bed that I am dying. You know the word “cancer” is like a death sentence in our culture. (participant 3)

They used to hug me, they used to cry, like I am going to die tomorrow. Like, one of the females, who came to meet me, she said that this is the time you should ask for Istighfar [forgiveness], and you should clean your closet and distribute all your jewelry, and do this and do that. (participant 8)

I do not like the pity look. Things make you feel you are weak. I tried to hide my diagnosis from others. (participant 32)

Because I do not want to feel [pity look] from anyone. I want them to treat me as they do with others; I do not want to feel that I am special because I have a specific need [cancer]. . . . I do not like the feeling that anyone deals with me with a pity look. (participant 32)

People think that you got cancer—the end. You are going to die. After that, there is nothing but the end of your life. (participant 10)

Privacy: Some participants stated that their diagnosis was private, and they only wanted to share it with those close to them.

I shared it with my immediate family, my wife—kids were young at the time—just my wife, some of my closest friends. I did not really tell a lot of people, just people close to my family, because this is a very personal thing. (participant 31)

It is our nature; we do not want to share our cancer with others. I only informed one of my friends in the community. (participant 32)

I kept to myself and my family. I did not share it. I think it was because, at that point, it was something that I had to go through [by myself]. (participant 5)

Perceived Strong Social Support

Many cancer survivors expressed their appreciation for the support they got from others and focused on physical support dimensions. Participants identified two major sources of support: (a) family and the Muslim community and (b) social support groups and healthcare providers.

Support from family and Muslim community: Many participants appreciated the support they received from family and Muslim community members and described how it helped them deal with their cancer experience.

All my friends were very supportive. They used to visit me. This helps me to forget what I have and helped me deal with cancer diagnosis effectively. (participant 20)

I got excellent support from my brother that even was beyond my imagination. (participant 10)

I knew that many people were praying for me. When I see that, I feel their prayers. I was able to see this transition to my well-being. (participant 5)

They used to spend the night with me at the hospital and after we started the treatment. Someone was always with me at every single appointment for the chemo session, so I was never alone. That really helped too. (participant 26)

Support from social support groups and healthcare providers: Several survivors appreciated the importance of social support groups but preferred to participate in a Muslim support group. Many survivors appreciated support from healthcare providers.

The Muslim community, doctors, and the team were very helpful. My surgeon was helpful. My oncologist and nursing team were great. (participant 14)

I think [the social support group] is good, but I would like to participate only if it is a Muslim people group. (participant 28)

There is a very big need for making a Muslim support group—not only for the patient, but also for the caregivers. (participant 3)

You just talked with other people with cancer. It really helps. Not a burden shared, but a burden halved. (participant 4)

Making an Effort to Keep Up With Religious Practices

Many survivors expressed making an effort to maintain their mandatory religious practices. They stated that they were trying to keep up with their religious practices to please God and keep his blessings. Specific statements illustrating this theme included the following:

I started praying more, going to the masjid [worship place], trying to pray at the masjid more than to pray at home, increasing my good deeds. (participant 17)

I did not miss any of my prayers, even during the [difficult] time. It was in my senses. I used to do Tayammum [ritual purification for prayer when water is not available]. (participant 3)

I do more religious practices. Going to the mosque, cleaning the mosque, washing the floor of the mosque. (participant 2)

I noticed a colostomy attached to my abdomen after my colon surgery. I was shocked. I was afraid that this colostomy is going to impact my cleanliness and readiness to do my prayers. (participant 20)

It was very difficult to do my prayer. At the beginning [of cancer], I was doing it. But in the middle, I was very, very sick. I was in the wheelchair. I was not able to walk, and then I developed blood clots, so it was very difficult to do my prayers. (participant 3)

Perceived Discrimination in Healthcare Settings

Several participants perceived some discrimination from healthcare providers based on their religion or race. They indicated they felt they were treated differently because of their Muslim appearance or their skin color.

There was one doctor, he made [diagnosis] difficult because he had some preconceived notions that the color of my skin and by looking at my family that I might have traveled to Pakistan, India a lot. He was convinced that I had malaria, and he kept looking at the infectious disease perspective, although the other team members of the hospital kept asking for permission to do other tests. It would probably have helped to find cancer sooner, but he kept it turning it down; he was not really handling the case properly. (participant 26)

I was originally concerned because, you know, I wear hijab [head covering]. You just never know. I would say be as compassionate as possible, sincere, and respectful if wearing hijab or not. Sometimes if you wear hijab, you wonder if you would come across discrimination. (participant 15)

Maybe there are some people, if they knew that you are a Muslim, then they might consider you as a terrorist. (participant 12)

We are not different than anybody else. We want to be told the truth, we want to be helped, and we want to have respect like everybody else. It is not that difficult, and you think those kind of prejudices are in medicine only. There are larger social injustice issues. That is the reason you do some of these discriminations to the citizens. You knock some of these down, so people do not have this fear of Muslims when we come to get the treatment and hopefully cures. (participant 16)

I know a lot of Muslim people feel shunned because of their beliefs. They are not treated the same way as the White people; they are treated as a different sort of being. They are not looking at you as humans, but they are looking at you as Muslims. (participant 7)

Importance of Religion and Cultural Awareness

Many survivors addressed the importance of healthcare workers being aware of their religion and of their culture. They felt that healthcare providers should learn about their Muslim beliefs and religious needs and be culturally sensitive because, often, they were not. Many participants appreciated having a Muslim healthcare provider who shared their religion.

There was one resident who was a Muslim. When he was examining me, I noticed that he was not looking at me; he was just touching and feeling any lump, and then I realized the difference. (participant 3)

During the time of treatment, they were very insensitive during the time of radiation; they would try to expose you on the table and that kind of stuff, which is religiously insensitive. (participant 16)

They came in and they saw my sister is praying, so they said, “I am very sorry to bother you.” After that, they put a sign on the door that we pray five times during the day. But they did not know that earlier; if they would, they could have put the sign on earlier. (participant 17)

Our culture and religion all have an impact. These issues are not taken into consideration. (participant 12)

Lucky that we are in southeast [U.S. state], and people are very aware of Muslim needs in terms of food. (participant 17)

Discussion

Cancer survivors experience many difficulties because of the disease and treatment, including physical, emotional, psychological, and social issues. Religion and culture may affect how survivors deal with their experience of cancer. Prior research on the experience of Muslim cancer survivors is sparse and has been conducted primarily in Islamic countries (Ahmadi et al., 2019; Alaloul et al., 2016; Errihani et al., 2008). Therefore, in this study, the authors aimed to gain an understanding of the cancer experiences specifically of adult Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States.

The authors found that religion and culture have a great influence on Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States. Many participants described their cancer experience based on their belief in God. Being connected to God through remembering his supreme power helped them to cope with cancer by bringing them inner peace. This finding was consistent with previous studies conducted in the Middle East showing that spirituality was an important factor in helping survivors deal with their cancer experiences (Alaloul et al., 2016; Karabulutlu et al., 2019; Shaheen Al Ahwal et al., 2016). Participants also addressed the importance of being trustful in God and accepting his will and how that helped them gain support and guidance from God in their cancer journey. In general, Muslims believe that illness or wellness is God’s will (Wehbe-Alamah, 2008).

Many Muslim survivors expressed the belief that their cancer diagnosis is a trial from God, and by succeeding in this trial through acceptance and patience, God will help them overcome difficulties in life, and they will receive forgiveness in the hereafter. According to Islam, individuals who receive illness and death with patience and prayers will be rewarded (Dewi et al., 2013). Therefore, understanding how the Islamic religion can shape the cancer experience of Muslims, particularly those residing in Western countries, will help healthcare providers deliver religious and culturally sensitive interventions to reduce cancer disparities in diagnosis and treatment. Healthcare providers can seek guidance from Muslim chaplains in coordination with patients to meet their spiritual needs and to enhance patience and hope during difficult times.

Of note, many Muslim survivors stated they chose to hide their cancer diagnosis and suffering from others for several reasons, including worrying about the feelings of others who know about their cancer. Other participants indicated they hide their cancer from the public to avoid the negative comments and reactions toward cancer survivors in the Muslim community. These findings are consistent with previous studies conducted with cancer survivors in Muslim countries (Alaloul et al., 2016; ALmegewly et al., 2019). Hiding suffering and feelings because of cancer stigma can prevent survivors from seeking help to meet their needs and coping with the cancer experience, and can influence health outcomes (Chambers et al., 2015). Cancer survivors who expressed their feelings and thoughts were more likely to feel peace and comfort (Menichetti et al., 2016). Healthcare providers are encouraged to discuss concerns about hiding cancer diagnoses and suffering with Muslim cancer survivors, particularly those residing in Western countries, to ensure they receive appropriate support resources.

Although many cancer survivors hide their cancer from others, participants also expressed appreciation for the support they received from family and community members. This support helped them cope with their cancer experience. The absence of extended Muslim families in Western countries placed increased pressure on those family members in the United States (Al-Sharmani et al., 2019), particularly when a family member was diagnosed with cancer. Many other Muslims residing in Western countries live in small Muslim communities (Barise, 2005; Jisrawi & Arnold, 2018). A study by Obeidat et al. (2012) focused solely on the experience of women receiving treatment for early-stage breast cancer in one Muslim ethnic subgroup in the United States. In this single previous study, family and community support were important in helping the women cope with their treatment experience. In the current study, many survivors appreciated the support they received from healthcare providers and noted importance of social support groups. However, participants who were interested in support groups indicated they would prefer to join groups with other Muslims. Previous studies highlighted the importance of a support group that addresses issues related to the Muslim faith and culture (Alaloul et al., 2016; Obeidat et al., 2012). Therefore, a future goal is to study the influence of Muslim cancer support groups on the experience of Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States.

Several participants in the current study indicated they experienced discrimination in healthcare settings related to their religion and race. They felt that this discrimination influenced their physical and psychosocial well-being. Perceived discrimination may increase healthcare disparities (Padela, Gunter, et al., 2012; Padela, Killawi, et al., 2012) and negatively affect survivors’ health outcomes, including satisfaction with health care (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2010; Sirois et al., 2013).

Many survivors in the current study acknowledged the importance of healthcare providers’ awareness of their culture and religion, which can help in providing more culturally sensitive care. In non–Muslim-majority countries, many Muslims have expressed their concerns regarding healthcare providers’ lack of knowledge of their faith, religious practices, and culture (Reitmanova & Gustafson, 2008; Shah et al., 2008). This lack of understanding may affect the patient–provider relationship and negatively affect healthcare outcomes and patient satisfaction with care (Kagawa-Singer et al., 2010; Padela, Gunter, et al., 2012; Wehbe-Alamah, 2008). Cultural and religious competence is a key element in decreasing health disparities among a rapidly growing group of cancer survivors.

The authors found that some Muslim cancer survivors preferred to maintain their mandatory religious practices even during difficult times, including hospitalization. According to the religion of Islam, Muslims are excused from mandatory religious practices for medical reasons (Myers et al., 2019). It is possible that some Muslims with a cancer diagnosis may choose not to have a colostomy to maintain their cleanliness for prayer; others may continue fasting during their holy month (Ramadan) despite being allowed to break their fast for a valid medical reason (Zeeneldin & Taha, 2012). Healthcare providers need to discuss these practices with survivors and include a chaplain during the discussion to help in resolving these issues.

Strengths and Limitations

This is the first study to focus exclusively and comprehensively on the experiences of a rapidly growing yet understudied group of cancer survivors—Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States. The authors included similar numbers of women and men to better understand experiences across genders. Another strength was the ability to recruit participants from across the United States. A limitation was the lack of input from members of the Muslim community, such as chaplains or faith leaders. In Muslim communities, individuals with difficult situations, such as cancer survivors, usually seek help from faith leaders to discuss their emotional difficulties and personal feelings. Interviewing faith leaders may provide more information about the experience of Muslim cancer survivors residing in the United States. Future studies will address this limitation to provide greater breadth in understanding the experiences of Muslim cancer survivors.

Implications for Practice and Research

Healthcare providers in the United States will be caring for an increasing number of Muslim cancer survivors. The ability to deliver religious and culturally competent care to these survivors is key to improving their experiences. Partnership with Muslim chaplains and Muslim community leaders can help healthcare providers to explore and meet Muslim survivors’ religious needs. Healthcare providers are encouraged to discuss cancer stigma with Muslim survivors, as well as its effect on seeking help from the community. Healthcare providers should focus on educating those in Muslim and non-Muslim countries about the needs of Muslim cancer survivors. Future research is needed to move beyond describing the experience of Muslim cancer survivors to developing empirically testable, religious, and culturally sensitive interventions to improve the cancer experience. A future goal is to test the impact of a support group sensitive to Muslims’ faith and culture on their cancer experience in the United States.

Conclusion

There is a growing need to understand how Muslim survivors residing in the United States react to the diagnosis of cancer and cope with cancer treatments and psychosocial difficulties. Identifying, understanding, and meeting patients’ religious needs, as well as understanding their cancer experience, may reduce disparities in cancer care and enhance health outcomes for Muslim cancer survivors.

About the Author(s)

Fawwaz Alaloul, PhD, MSN, MPH, RN, is an associate professor at Sultan Qaboos University in Muscat, Oman; Barbara Polivka, PhD, RN, FAAN, is the associate dean for research in the School of Nursing at the University of Kansas in Kansas City; Sadaf J. Warraich, MBBS, MPH, is a research assistant at the University of Louisville in Kentucky; and Michael A. Andrykowski, PhD, is a professor emeritus in the Department of Behavioral Science in the College of Medicine at the University of Kentucky in Lexington. This study was supported, in part, by a research grant from the Oncology Nursing Foundation. Alaloul, Polivka, and Andrykowski contributed to the conceptualization, design, and manuscript preparation. Alaloul and Warraich completed the data collection and provided statistical support. All authors provided the analysis. Alaloul can be reached at f.alaloul@squ.edu.om, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted January 2021. Accepted May 3, 2021.)