Experiences and Concerns of Lesbian, Gay, or Bisexual Survivors of Colorectal Cancer

Purpose/Objectives: To identify the experiences and needs of lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) survivors of colorectal cancer (CRC) and to expand the current understanding of LGB survivorship by obtaining in-depth knowledge of survivorship among individuals with a cancer other than breast or prostate.

Research Approach: Qualitative, semistructured individual interviews via telephone.

Setting: Participants were recruited using social media, flyers, word of mouth, and contact with LGB and cancer organizations during a four-month period.

Participants: Eight LGB individuals with a diagnosis of stage III CRC from 2009–2014.

Methodologic Approach: All interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed verbatim. Thematic analysis performed by more than one analyst was used for the interview transcripts.

Findings: Participants described experiences with social support and isolation, cancer care from an LGB perspective, and substantial economic impacts of their cancer diagnosis. In addition, they reported struggles with health insurance coverage, employment, and housing during and after their treatment for CRC.

Conclusions: In addition to issues regarding sexual identity disclosure and social support, economic impacts of CRC exist; these are likely critical to healthy survivorship in LGB men and women.

Interpretation: Attention should be paid to the economic impact of CRC on LGB individuals, along with issues of social support and sexual identity disclosure. Oncology nurses could play an important role in determining the economic and social needs of patients with CRC, accepting the often nontraditional support networks of LGB individuals, and facilitating disclosure of an LGB identity.

Jump to a section

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer in men and women (American Cancer Society, 2017). However, CRC survivorship is understudied. To the current authors’ knowledge, CRC survivorship among lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) individuals has never been studied, despite research indicating that members of this population have greater risk factors for CRC (Institute of Medicine, 2011; Reuben, 2007), as well as higher CRC incidence, prevalence, and mortality (Boehmer, Ozonoff, & Miao, 2011; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2011), than the general population. Some studies of LGB individuals’ overall cancer survivorship included CRC along with other cancers (Margolies & Kamen, 2015; Matthews et al., 2016), but the experiences of LGB survivors were not analyzed by cancer type. What is known about LGB survivorship stems primarily from studies of breast or prostate cancer (Boehmer & Elk, 2015; Simon Rosser et al., 2016). Studies of survivorship by sexual orientation are inconsistent. Some have indicated that LGB and heterosexual survivors have similar quality of life, whereas others have concluded that LGB survivors have worse quality of life compared to heterosexuals (Boehmer, 2015; Boehmer, Miao, & Ozonoff, 2011; Simon Rosser et al., 2016; Ussher et al., 2016). Reasons for these inconsistencies in study findings are unclear, and, given that studies mostly focused on prostate and breast cancer, patients’ gender and cancer type are confounded. The current authors sought to expand the current understanding of LGB survivorship by focusing on a cancer other than breast or prostate. Because CRC survivorship has never been studied among LGB individuals, this study’s purpose was to identify the experiences and needs of male and female LGB survivors who have a diagnosis of CRC. The goal for this initial study was to determine the issues most salient to LGB CRC survivors to (a) ensure that the identified issues were included in future research about quality of life among CRC cancer survivors, (b) raise awareness of the experiences faced by LGB individuals in cancer care settings, and (c) provide preliminary data for survivorship care models that address the needs of LGB survivors.

Methods

The study was approved by the Boston University Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment and Procedures

Community-based purposive sampling was employed in recruiting LGB participants for the study using social media, flyers, word of mouth, and contact with about 35 LGB and cancer organizations during a four-month recruitment period (September to December 2014). The recruitment message for the study asked potential participants to contact the research team by email or telephone. Participants were eligible for the study if they met three criteria: (a) five or fewer years since CRC diagnosis, (b) cancer at stage III or less at the time of the interview, and (c) self-identification as a sexual minority. Thirteen individuals contacted the research team and were screened for eligibility. Five individuals did not meet eligibility criteria for the study because their diagnosis was more than five years ago or they were diagnosed with anal cancer; the remaining eight individuals were eligible. Recruitment continued until no new themes were identified in the interviews. After informed consent was obtained from eligible participants, telephone interviews were conducted; these were audio recorded and lasted 30–45 minutes. A semistructured interview guide—comprised of questions about survivors’ current well-being, interactions with the healthcare system and providers, and their perceptions of their cancer experience as individuals in a sexual minority—was used. At the end of each interview, sociodemographic information was collected using structured questions. Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service. After transcription, the first author reviewed each transcript with the audio recording to verify its accuracy.

Analysis

Summary statistics of the screening and sociodemographic data were calculated. The interview transcripts were analyzed by two of the authors using procedures and principles of qualitative data analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1990; Ulin, Robinson, & Tolley, 2004). Specifically, each transcript was coded to be inductively and deductively consistent with the domains laid out by the interview guide. To apply qualitative rigor, two of the authors discussed differences in coding, and then recoded and made refinements in codes to capture the interviewees’ meanings and experiences. The finalized codes were then grouped into higher-level domains, which used lower-level codes as the underlying structure (e.g., housing and employment were grouped under the economic impact domain). Because the current authors were interested in general themes of participant experiences (e.g., colostomy), by design, a theme was retained when at least three of the eight participants addressed it, excluding infrequent or single occurrences of themes from further analysis. Finally, through ongoing discussion between two of the authors and with input from the third author, the illustrative quotes for each theme were selected for the text.

Results

Participant Characteristics

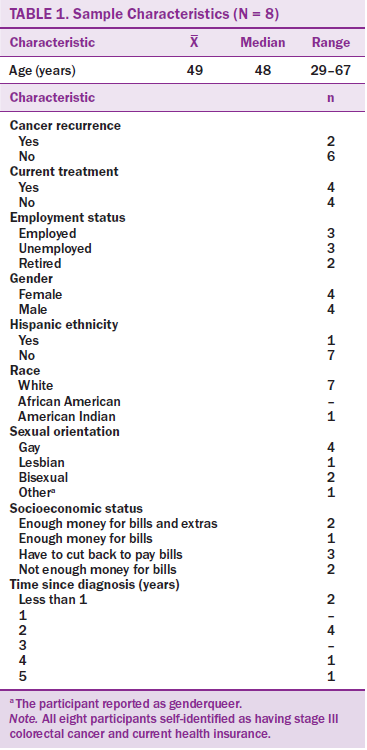

Telephone interviews were completed with eight individuals who had received a diagnosis of stage III CRC within the past five years; two of these individuals had since had a recurrence, and four were currently undergoing treatment (see Table 1). Five reported as lesbian or gay, two reported as bisexual, and one reported as other (genderqueer). In addition, seven self-reported as non-Hispanic White, and one self-reported as Hispanic for ethnicity and as American Indian for race. Of the three employed participants, two were currently on leave through the federal Family and Medical Leave Act. Although all the participants reported having health insurance at the time of the interview, coverage had been unstable for most participants since the time of their diagnosis.

All participants first grounded their remarks about their experience with CRC by describing their diagnosis and treatment as distressing and difficult. Many participants talked about a “new normal” after cancer. Participants described common symptoms during and after treatment, including fatigue, neuropathy, wounds after surgery, difficulties adjusting to stomas, changes in appetite, and what one woman described as the “cancer fog” (defined as cognitive impairment, which may include problems with concentration and memory, difficulty with retrieving words, and issues with multitasking). Three major themes emerged from the data: (a) social support and isolation, (b) the economic impact of CRC, and (c) LGB identity and CRC care.

Social Support and Isolation

Social support was an issue for survivors at the time of treatment and once treatment was completed. One 55-year-old woman described the support she received during her treatment.

Actually, in many ways, the church is my support network. But it’s kind of in a weird way that they’re my support network when I’m there. But when I’m not there, they’re not, you know what I mean. . . . It was kind of like an arm’s length support.

A 64-year-old male participant who was still in treatment at the time of the interview discussed the three days per week he underwent treatment—a time during which he was not allowed to leave his home.

I wish I did [have visitors]. But . . . most people I know, they’re either working, or, you know, people . . . I think tend to be a little more involved in their own self and a little more involved in what they want to do. . . . You know, the support is there, if I really need it. Say a ride to a procedure where I’m going to be given IV sedation or something like that, usually I can get it, but in terms of support while I’m doing treatment, coming over here . . . my friends are kind of missing on that, and that’s a little disappointing.

A 52-year-old woman described feelings of social isolation when she was talking about her “new social life” after cancer. She said that, because of fatigue and other issues that she is still experiencing after treatment, she cannot make plans with friends like she used to.

Even just going to dinner with friends, it’s like, now it’s better, but during the course of treatment, it’s like, “You want to go to dinner?” . . . OK, today’s a good example: [Someone might say,] “Today’s Tuesday. Do you want to go to dinner on Saturday?” [However,] I don’t know how I’m going to feel on Saturday, you know? Yeah, before I was, I think I would go, “Yeah, yeah, sure, let’s go out on Saturday night.” [Now] I don’t know how I’m going to feel on Saturday. So I have [to think], “Is it a chemo week? Is it a non-chemo week?” All those things factor in and change it.

The Economic Impact of Colorectal Cancer

Employment, health insurance, and housing are three ways in which LGB survivors reported being economically affected. Regarding employment, one interviewee was retired, one retired after being diagnosed, two reported losing their job as a result of their cancer diagnosis, and one reported having been forced to decline a full-time position because of cancer. A 52-year-old woman, who had worked as a call center manager in a medical firm, described losing her job.\

[My employer] called me [after I was on long-term disability for treatment] and said, “We got the latest notes from your doctor, and since your cancer treatment is not being completed in a timely fashion for us, we’re going to have to rescind your employment, but you can keep your insurance and you can keep your, uh, your [long-term] disability.”

A 41-year-old man said that “work was really one of the biggest sources of stress.”

I went on . . . the [Family and Medical Leave Act]. . . . I’ve almost used all of it, and now I have to do six months chemo. You know, once that runs out, if I’m still sick or if I still can’t physically take myself to work, then, you know, there’s a good chance that I’ll lose my job. Then, if I lose my job, I lose my benefits that day.

A 44-year-old woman reported that she worked in the technology industry in San Francisco and tried to work during her treatment. She was unable to attend work regularly and she said that her boss “got a little paranoid about that and . . . [she] was fired.” Without an income after losing her job, she was forced to move in with family members in a different state who did not approve of her sexual orientation, far away from her social network.

A 55-year-old woman described how her cancer diagnosis limited her employment opportunities for teaching full-time.

Before I got cancer . . . I was on my way to, but I hadn’t yet gotten, a full-time position. And I had gotten my advance math endorsement. I had my full year [substitute teaching in] advanced math, and I was hoping to get the [full-time] position, and then I got cancer.

In addition to losing jobs and job opportunities because of the cancer diagnosis, a 41-year-old man talked about what he perceived as discrimination when he was looking for a job after his treatment ended. He, like many of the participants, was not able to work for nearly two years during his cancer treatment.

Trying to go back to work has been . . . difficult. How do you tell somebody that you were trying to get a job with why you were out of work in my particular case for you know, two and a half years, or whatever it’s been, about telling them that I have cancer? And [that] it may recur, [that] I might not be able to finish this job. . . . I may have more doctors’ appointments along the way.

He described his experience at a job interview.

I had an interview with this company and that company . . . and everything would seem to be going great because . . . I have lots of experience, management, leadership, and curriculum development in finance, and so I’d go through this, and I would be talking to them, and I was thinking, “Oh, this is going so, so great.” And [then] they would get to the point of, you know, like, “Why haven’t you worked since 2011?” And I say, “Oh, I had cancer.” And then I never hear from them again.

Ultimately, after working with a career counselor in his job search, he decided not to mention that he had cancer, and instead talked about some volunteer work and community work that he did during the time that he was in treatment.

Losing a job meant lost income for participants, but also concerns about health insurance coverage. Nearly all the interview participants described how retaining health insurance was a struggle. Many recounted that they did not have health insurance when they first noticed symptoms, or that they did not have insurance in the years leading up to their diagnosis and, therefore, did not receive regular checkups. A 44-year-old woman who lost her job after her diagnosis and had to move in with family also lost her health insurance.

I didn’t have the insurance, and I was in Minneapolis a year and a half fighting through Medicare paperwork. [I had] a port that [had] to get a monthly maintenance, and I [didn’t] have insurance, so then I [went] to an emergency room. Then, I have all these $900 bills every single month. . . . You know, I moved to, I went to different hospitals every time because I [didn’t] think they were going to [maintain the port] for me when they see I didn’t pay [the $900].

Lack of health insurance played a pivotal role in a male participant’s story about how he was diagnosed with CRC.

Earlier in that year, in March 2012, I had severe abdominal pain, and I had no idea what the problem was. So, I went to the [emergency room] that night, and they gave me an ultrasound. I didn’t have insurance at the time. . . . They told me I have [irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)]. So, I went . . . through the rest of the next six or eight months in that year of 2012 thinking I had IBS. And then, in October of 2012 when I had the same pain again, that was when they told me [about the cancer].

A female participant who worked as a substitute teacher talked about having to keep close track of when she was covered by health insurance because of the temporary nature of her employment.

I had no insurance all of last year. [This year] I had insurance for two months, from May to June. And then I didn’t have it again, and now I got it back again for October, and now I’m good for next year. It was not a very fun two months there because . . . every day I was working, going to a doctor’s appointment, working, and go to another doctor’s appointment. It was horrible . . . trying to get the colonoscopy, trying to get all these things done in two months.

The only positive story about health insurance came from a retired 64-year-old man. He talked about the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and how it has helped him financially.

I was paying $1,571.85 a month for my insurance. When I switched to [name of insurance provider] on the Obamacare, the insurance exchange, the marketplace, I qualified for a tax, a monthly tax subsidy and cost sharing. And my monthly premium was brought down to $336.43. That was for the year 2014. With 2015, after I saw [name of doctor] at [name of cancer center], I realized that I needed to switch to a policy that would cover me there so that I could follow up with him. And then my premium went from $336.43 a month with [name of insurance provider] to $71.04 a month with [name of insurance provider]. So that’s where I am now: $71.04 a month. That really helps me survive tremendously by defraying those extra costs that I would’ve had.

Finally, CRC affected participants’ housing situation, including the loss or risk of losing their housing, because of changes in finances from job loss, eviction, and an inability to live alone during treatment. For one 55-year-old woman, the job loss she experienced nearly resulted in her losing her home.

I think [people at the church] supported me to a tune of like $19,000 over that year [during treatment]. [By] the end of July, I couldn’t work anymore, and then I had my surgery in August, and so . . . I would’ve ended up homeless because there’s no way I could’ve paid rent without working.

A 44-year-old woman reported that she was evicted from her apartment. After losing her job, she had to move in with family members who did not approve of her sexual orientation and with whom she did not have a good relationship. When a 41-year-old man was diagnosed, he was living alone, about six hours away from his mother. Shortly after his diagnosis, he moved in with his mother for the support.

Lesbian, Gay, or Bisexual Identity and Colorectal Cancer Care

Three aspects comprised this theme: (a) disclosure versus nondisclosure, (b) the need for providers not to make assumptions, and (c) the need for providers to realize that individuals’ social support networks may appear different or unconventional compared to those of heterosexual patients. Participants reported that they were more likely to disclose their sexual orientation to nurses and auxiliary medical personnel than to doctors. When asked about the level of openness she has with her medical providers, a 29-year-old woman described her relationship with her doctors as a “professional-type relationship.”

I got pretty close with my nurses because I spent the most time with my nurses. You know, we would chat about what’s going on in our lives [during treatment]. But . . . my doctors, you know, when I see them through appointments, we really just talk about what’s going on medically.

A 55-year-old woman reported that she did not remember “coming out” to any of her providers.

I mean, I might have to the oncologist because he’s so cool. I might have been, you know, because when you, when the people that you don’t think about, you come out, and you don’t even think about it. . . . Where . . . the surgeon, it never came up, and I didn’t feel comfortable bringing it up because it seemed like a non-issue to him.

Generally, participants tended to feel that they were just as open with their providers as they were in their lives. A 41-year-old man said he was the same with his providers as he was with others in his life: “I think it’s extremely important for them to know who I am . . . so that they can . . . [play] a more active role in my overall health.” Some participants reported being “out” to their providers, although they did not recall actively disclosing their identity. A few participants talked about living in a place where the culture is very open when asked about disclosure to providers. A 52-year-old woman living in northern Colorado said most of her providers were in Boulder.

It’s . . . fairly liberal. . . . It’s a progressive place. . . . When I fill out my paperwork with any doctor, if it says “spouse,” I put in [my partner’s] name. I try and check “married.” [But] am I really that explicit about it? No, I think if you look at me, you’d probably pretty much have an idea.

The idea that disclosing one’s sexual orientation was not relevant to cancer treatment was talked about frequently and equally by male and female participants. For example, a 64-year-old man discussed his nondisclosure to an oncologist, saying, “He is just such a wonderful doctor and just covers everything when he talks to you. I never really felt that my gayness was a factor in the sense of what I’m dealing with him.” Participants noted that they sometimes felt if they were seeing a specialist or a provider just once, the nature of the visit may not warrant disclosure. The 64-year-old man who did not disclose to an oncologist mentioned a provider that he saw only once: “I didn’t feel that [my sexual orientation] was very much a factor in terms of what I needed to decide in my appointment with him, so it really wasn’t brought up.”

One 41-year-old male participant reported actively disclosing to his surgeon during their first meeting.

During our first meeting, I told him that I had a very personal reason for wanting to stay intact, and the reason I used that word is because the tumor was at the top of my rectum and into my colon. . . . [The doctor] right away said “sexual activity” in . . . a very nonjudgmental way, and he said, “Yes, you will still, there will still be a good portion of your rectum after all of this is said and done, and you might not want to try [anal sex] for [about] six months to a year to make sure everything [has] healed and everything.” I appreciate that [he said that to me].

Interview participants frequently mentioned instances when their providers had made heteronormative assumptions about them. A 55-year-old single woman described a situation in which her surgeon was explaining the treatment and how it would impact her vaginal area.

When [my surgeon] says, “You can have sex again,” I’m like, “Have you looked at what my vagina looks like? Try to put a hand up there.” Part of my vaginal area is white. There is no, very little blood circulation there. Basically, it’s been cooked [by the cancer treatment]. And so it’s very painful. When you think about having sex with a woman, it’s like, that’s not good. That’s gonna hurt. It’s all I can think of like, “That’s going to hurt.” When [my surgeon] said [I could] have sex, [it was] because his assumption is that it would be a penis. I didn’t say anything. I didn’t say anything because I know that was just [his] assumption. [That] kind of irritated the crap out of me because . . . [my surgeon] made that assumption.

In addition to respecting their dignity, participants described providers not making assumptions as a way that they could make the patient feel more comfortable and build trust. Most participants talked about how LGB individuals often have less traditional support networks in general, and this applies to their experience in the healthcare system as well. Only two participants lived with a partner during their diagnosis and treatment. A 41-year-old man said, “[I] gather support in nontraditional ways. Our families are not just the people that we’re biologically related to.” A married 52-year-old woman said that including the person’s support group is “imperative for that person’s health and recovery.”

Discussion

No gender differences were identified in CRC’s impact on LGB men and women, and many of the experiences of LGB CRC survivors are consistent with earlier findings of LGB survivors with other cancers. This is an important finding in that most LGB survivorship studies have focused on breast and prostate cancer, which implies that gender and cancer type are confounded (Boehmer & Elk, 2015; Simon Rosser et al., 2016). Previous studies identified disclosure of sexual orientation to providers as a unique issue for LGB survivors (Boehmer & Case, 2004; Durso & Meyer, 2013; Stein & Bonuck, 2001), and findings from the current study confirm this. Participants in this study made no efforts to actively conceal their sexual orientation and confided primarily with nurses rather than physicians. These results suggest that, if appropriately asked, LGB individuals are likely to disclose, and that asking routinely about sexual orientation, preferably in a conversation with the patient or at least on an intake form, may be helpful for oncology providers, including surgeons. In a study of 489 lesbian respondents, when physicians asked about sexual orientation, 100% disclosed information about their sexual orientation (Steele, Tinmouth, & Lu, 2006). Providers asking about sexual orientation may also encourage those who may not consider their sexual orientation to be relevant to treatment to disclose their sexual identity (Boehmer & White, 2012). Knowing patients’ sexual orientation allows for a shift in communication and can help providers avoid heteronormative assumptions and language used in the context of providing care, as experienced by the LGB CRC survivors in this study.

Consistent with the literature on cancer survivorship, including LGB individuals, social support is a salient issue from diagnosis to treatment and beyond (Kamen, Smith-Stoner, Heckler, Flannery, & Margolies, 2015; Liao & Brunner, 2016). LGB CRC survivors reported receiving support from friends and family when specifically asked, but longed for unsolicited support. In addition, the expressions of support described were more material than emotional or psychological, such as providing transportation or dropping off food but not staying to talk. As one participant observed, support received was often at arm’s length. However, study participants did not report asking for support unless it was something specific, like a ride to an appointment. The reports of isolation by the interviewed LGB CRC survivors raise concerns about whether support of LGB survivors varies by cancer type. Future studies should address whether LGB CRC survivors receive less support than LGB survivors of other cancers, as well as heterosexual survivors.

The most novel findings of the study are the details describing how CRC affected these LGB survivors economically. The major economic impacts of CRC reported by the study participants related to employment, health insurance, and housing. Most of the LGB CRC survivors interviewed for this study experienced loss of employment as a result of their cancer diagnosis from the illness itself, the side effects of treatment, and/or the length of treatment. Studies suggest that low economic status and poverty are more prevalent for LGB individuals compared to heterosexual individuals (Badgett, Durso, & Schneebaum, 2013; Brown, Romero, & Gates, 2016). Participants also recounted facing discrimination because of cancer when trying to reenter the job market because of their history of CRC, the chance of recurrence, and the length of time they were out of the workforce. These findings raise questions about whether job loss and economic decline is greater for LGB cancer survivors compared to heterosexual survivors. In addition, most participants reported lack of health insurance either leading up to their diagnosis or thereafter, usually as a result of job loss. The one positive experience related to health insurance was a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which many hope will bring an end to the longstanding inequity of LGB individuals being less likely to have adequate health insurance compared to heterosexual individuals (Buchmueller & Carpenter, 2010; Institute of Medicine, 2011). The third economic aspect that emerged from the interviews related to housing. In this study, the LGB CRC survivors reported changes in their housing situation from loss of employment and income, but also because they were unable to live alone during treatment as a result of the length of treatment, seriousness of the illness, or side effects of treatment.

Limitations

Several limitations to this study exist. The study was exploratory in nature and, given the qualitative data and the nonprobability sample used, these findings can illuminate LGB survivors’ needs and concerns but do not allow for any generalization about LGB CRC survivorship. The current authors hope the findings identify factors, including the economic impact of CRC and the lack of available support, that should be studied in depth in future LGB cancer survivorship studies. In addition, although participants were geographically distributed across the United States, the small sample size prohibited the identification of key factors in CRC care that may vary by availability of health and social service resources. Also, the themes identified were based on data collected from participants who self-reported having stage III CRC. The satiation in themes identified with relatively few participants interviewed is likely because of this lack of variability in stage of CRC in the sample. Different or additional themes may have been identified with the inclusion of additional participants at other CRC stages and/or the use of a different data collection methodology (e.g., in-person, Internet). Because a heterosexual comparison group was not included, the current authors are unable to determine the extent to which the issues raised by participants in this study are unique to LGB CRC survivors.

Implications for Nursing

The findings of this study suggest that LGB CRC survivors have economic and social needs, and oncology nurses and other healthcare providers can play an important role in the quality of life of CRC survivors. Attention should be paid to the economic impact of CRC on LGB individuals in addition to social support, heteronormative assumptions during cancer treatment and follow-up care, and the facilitation of sexual identity disclosure.

Study participants voiced feelings of isolation during and after treatment, as well as the fact that many LGB individuals obtain support from nontraditional networks, such as close friends or ex-partners, rather than spouses or immediate family (Grossman, Daugelli, & Hershberger, 2000). Nurses and other healthcare providers can help with these issues by being attentive to signs of social isolation and routinely asking about social support. They can also bolster existing support by accepting and welcoming LGB CRC survivors’ relationships and social networks into clinical encounters. Additional research is needed to fully assess nurses’ contributions to satisfactory clinical encounters for LGB cancer survivors and to deepen understanding of how nurses can improve LGB cancer survivorship.

Economically, obtaining and maintaining health insurance coverage, employment, and housing were substantial concerns for all participants. The findings suggest that LGB CRC survivors may benefit from support and services, such as routinely being asked about problems or concerns with health insurance, employment, and housing; receiving assistance with navigating new health insurance marketplaces and paperwork; and obtaining referrals to appropriate services, such as housing support or career counseling.

Disclosure of sexual identity and acceptance of disclosure by healthcare providers has been found to be associated with improved health outcomes and satisfaction with care (Durso & Meyer, 2013; Mosack, Brouwer, & Petroll, 2013). In this study, only one participant reported actively disclosing his sexual identity to a healthcare provider, but, at the same time, none of the participants actively hid their identities. Nurses and other healthcare providers can facilitate disclosure by routinely asking about identity with all patients and consistently and appropriately collecting information on medical and social history forms. Participants reported concerns during follow-up care related to providers making assumptions about their sexual identity. Although encouraging disclosure may mitigate some of these concerns, healthcare providers can also help by undergoing training specifically to raise consciousness about these assumptions and how to change patient–provider interactions.

Conclusion

Research on CRC is rare, and research on CRC among LGB individuals is absent—a particular strength of this study. Many needs of LGB CRC survivors may not be fully addressed in their cancer and postcancer care. Findings from this study suggest that, in addition to issues around social support and disclosure of sexual orientation, economic impacts of CRC on LGB men and women are likely critical to healthy survivorship.

About the Author(s)

Baughman is a project manager in the Department of Community Health Sciences of the School of Public Health at Boston University in Massachusetts; Clark is a professor at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Shrewsbury; and Boehmer is an associate professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences of the School of Public Health at Boston University. This research was funded by a grant (1R01CA181392-01A1) from the National Cancer Institute. Clark and Boehmer contributed to the conceptualization and design. Baughman and Boehmer completed the data collection and provided the analysis. All authors contributed to the manuscript preparation. Baughman can be reached at allysonb@bu.edu, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted July 2016. Accepted for publication September 20, 2016.

References

American Cancer Society. (2017). Cancer facts and figures, 2017. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/2ksCPAg

Badgett, M.V., Durso, L.E., & Schneebaum, A. (2013). New patterns of poverty in the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/18VyzPK

Boehmer, U. (2015). Breast cancer in lesbian and bisexual women. In U. Boehmer & R. Elk (Eds.), Cancer and the LGBT community: Unique perspectives from risk to survivorship (pp. 141–157). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International.

Boehmer, U., & Case, P. (2004). Physicians don’t ask, sometimes patients tell: Disclosure of sexual orientation among women with breast carcinoma. Cancer, 101, 1882–1889. doi:10.1002/cncr.20563

Boehmer, U., & Elk, R. (Eds.). (2015). Cancer and the LGBT community: Unique perspectives from risk to survivorship. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International.

Boehmer, U., Miao, X., & Ozonoff, A. (2011). Cancer survivorship and sexual orientation. Cancer, 117, 3796–3804. doi:10.1002/cncr.25950

Boehmer, U., Ozonoff, A., & Miao, X. (2011). An ecological analysis of colorectal cancer incidence and mortality: Differences by sexual orientation. BMC Cancer, 11, 400. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-11-400

Boehmer, U., & White, J.L. (2012). Sexual minority status and long-term breast cancer survivorship. Women and Health, 52, 71–87.

Brown, T.N., Romero, A.P., & Gates, G.J. (2016). Food insecurity and SNAP participation in the LGBT community. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/2p35J9Z

Buchmueller, T., & Carpenter, C.S. (2010). Disparities in health insurance coverage, access, and outcomes for individuals in same-sex versus different-sex relationships, 2000–2007. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 489–495. doi:10.2105/ajph.2009.160804

Durso, L.E., & Meyer, I.H. (2013). Patterns and predictors of disclosure of sexual orientation to healthcare providers among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 10, 35–42.

Fredriksen-Goldsen, K.I., Kim, H.-J., Emlet, C.A., Murcato, A., Erosheva, E.A., Hoy-Ellis, C.P., . . . Petry, H. (2011). The aging and health report: Disparities and resilience among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender older adults. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/2onM9aa

Grossman, A.H., Daugelli, A.R., & Hershberger, S.L. (2000). Social support networks of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults 60 years of age and older. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 55, P171–P179.

Institute of Medicine. (2011). The health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: Building a foundation for better understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Kamen, C.S., Smith-Stoner, M., Heckler, C.E., Flannery, M., & Margolies, L. (2015). Social support, self-rated health, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender identity disclosure to cancer care providers. Oncology Nursing Forum, 42, 44–51. doi:10.1188/15.ONF.44-51

Liao, J., & Brunner, E.J. (2016). Structural and functional measures of social relationships and quality of life among older adults: Does chronic disease status matter? Quality of Life Research, 25, 153–164.

Margolies, L., & Kamen, C. (2015). Needs of LGBT cancer survivors. In U. Boehmer & R. Elk (Eds.), Cancer and the LGBT community: Unique perspectives from risk to survivorship (pp. 203–226). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International.

Matthews, A.K., Hotton, A., Li, C.C., Miller, K., Johnson, A., Jones, K.W., & Thai, J. (2016). An internet-based study examining the factors associated with the physical and mental health quality of life of LGBT cancer survivors. LGBT Health, 3, 65–73.

Mosack, K.E., Brouwer, A.M., & Petroll, A.E. (2013). Sexual identity, identity disclosure, and health care experiences: Is there evidence for differential homophobia in primary care practice? Women’s Health Issues, 23, E341–E346. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2013.07.004

Reuben, S.H. (2007). Promoting healthy lifestyles: Policy, program, and personal recommendations for reducing cancer risk. Retrieved from http://bit.ly/2p2PwSd

Simon Rosser, B.R., Merengwa, E., Capistrant, B.D., Iantaffi, A., Kilian, G., Kohli, N., . . . West, W. (2016). Prostate cancer in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men: A review. LGBT Health, 3, 32–41. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0092

Steele, L.S., Tinmouth, J.M., & Lu, A. (2006). Regular health care use by lesbians: A path analysis of predictive factors. Family Practice, 23, 631–636. doi:10.1093/fampra/cml030

Stein, G.L., & Bonuck, K.A. (2001). Physician–patient relationships among the lesbian and gay community. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 5, 87–93. doi:10.1023/A:1011648707507

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Ulin, P.R., Robinson, E.T., & Tolley, E.E. (2004). Qualitative methods in public health: A field guide for applied research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Ussher, J.M., Perz, J., Kellett, A., Chambers, S., Latini, D., Davis, I.D.,. . . Williams, S. (2016). Health-related quality of life, psychological distress, and sexual changes following prostate cancer: A comparison of gay and bisexual men with heterosexual men. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13, 425–434. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.026