Findings on Family Issues During Relocation for Hematology Care

Purpose/Objectives: To present the findings from recent research on the experience of relocation for specialist treatment for patients in the hematology/oncology population.

Research Approach: Descriptive, qualitative study based on exploratory, in-depth interviews that were recorded, transcribed, coded, and thematically analyzed.

Setting: Leukaemia Foundation of Queensland, Australia.

Participants: A purposive sample of 45 individuals with hematologic cancer who had to relocate for specialist treatment.

Methodologic Approach: A descriptive, qualitative methodology actioned through open-ended, in-depth interviews with 45 participants who relocated for specialist treatment.

Findings: The findings indicate that relocation happens at a time when patients are particularly emotionally vulnerable from the shock of their diagnosis or relapse and the confrontation with a potentially life-threatening condition. During this time, when the need for the comfort and support of home and family is heightened, patients have to separate from their family and travel to metropolitan specialist centers. For patients from regional, rural, and remote locations, which are lengthy distances from metropolitan hospitals, the choice to return home during treatment is not a realistic option. Distance also can be a barrier that prevents family from visiting the hospital to provide support.

Conclusions: Individuals who have to relocate require psychosocial support. Because of the stresses associated with relocation for specialist care, many patients from regional, rural, and remote areas would prefer to be treated locally.

Interpretation: Understanding and responding to family issues associated with relocation for specialist treatment is an important aspect of oncology nursing care for patients who have to relocate from regional, rural, and remote areas. Because centralization of specialist hematology treatment is a worldwide trend, the findings have relevance to an international nursing audience.

Jump to a section

Hematologic malignancies are a diverse group of blood cancers classified in four broad categories. These categories include leukemia, Hodgkin lymphoma, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and myeloma (Hassan & Abedi-Valugerdi, 2014; Jemal, Siegel, Xu, & Ward, 2010; Rodriguez-Abreu, Bordoni, & Zucca, 2007; Sant et al., 2010). Historically, treatments for hematologic malignancies have been centralized in major metropolitan specialist centers (de la Morena & Gatti, 2011). Consequently, patients from regional, rural, and remote areas have to relocate to these metropolitan centers for treatments (McGrath, 1998; McGrath, Holewa, & Etcheverry, 2011). This article presents the findings from a study examining patients’ experiences of relocation for specialist hematology treatment. The article focuses on family issues, describing the effects on patients of leaving the comfort of their family and home to travel to metropolitan hospitals to receive their diagnosis and treatment. The findings are internationally relevant because the centralization of specialist hematology treatment is a worldwide trend (Brundisini et al., 2013; Payne, Jarrett, & Jeffs, 2000).

As explained by Given and Northouse (2011), oncology nurses spend more time with patients and their family caregivers than other professionals and are well positioned to provide support and guidance. Oncology nurses have a key role in providing clinical care and advocating for, supporting, and educating patients and their family at the point of diagnosis and along the continuum of care (Bilotti et al., 2011). Addressing family concerns and distress is acknowledged as an important focus for such nursing care (Grant & Ferrell, 2012; McLeod, Tapp, Moules, & Campbell, 2010). Understanding and responding to family issues associated with relocation for specialist treatment is an important aspect of nursing care for patients who have to relocate from regional, rural, and remote areas.

Methods

The research employed a descriptive, qualitative methodology actioned through open-ended, in-depth interviews with 45 participants purposively selected from the Leukaemia Foundation of Queensland patient database for 2012.

The research project was provided with full ethical clearance from the university human research ethics committee (HREC) at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, and formal consent was documented from all participants prior to the commencement of interviewing.

Sample

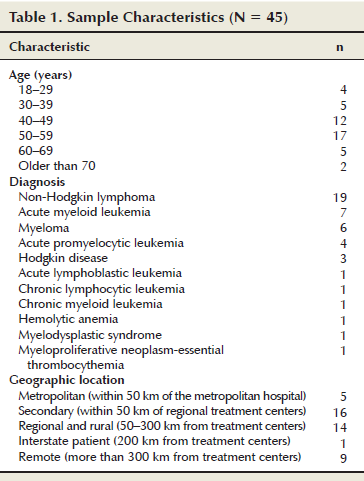

Because the intent was to include a diversity of experiences of individuals diagnosed with a hematologic malignancy in Queensland, the purposive sample (see Table 1) was based on a comprehensive inclusion of factors, such as age, gender, diagnosis, and geographic location. The large sample size and data analysis plan are consistent with previously published qualitative research projects on the psychosocial experience of patients with hematologic malignancies (McGrath, 2012; McGrath et al., 2011; McGrath & Holewa, 2007).

The selection of participants for the purposive sample was conducted by university-based researchers. Participant confidentiality was ensured because the LFQ was not aware of which clients from the 2012 database were selected. Potential participants received written information and a consent package by mail. The package provided full information, approved by the HREC, on consent and participation in the study. The project officer for the study then contacted potential participants by telephone, answered any questions, and invited participation in the study. On acceptance of participation, a time suitable to the participant was scheduled for the interview.

Interviews

All of the interviews were conducted by two researchers who had extensive experience in conducting qualitative research and who had worked for many years in the area of hematologic malignancies. The telephone interviews, which lasted about one hour, were audio recorded, transcribed verbatim, and stored in a password-protected computer program. The interviews started with an invitation from the interviewer for the participants to talk about their experience with diagnosis and treatment. From there, the interviews expanded to cover a range of topics relevant to the financial and psychosocial impact of relocation for specialist treatment.

Analysis

As Mayan (2009) explained, coding and analysis for naturalistic inquiries, such as this descriptive qualitative research project, should stay as close as possible to the data. Therefore, all of the participants’ statements were coded using NVivo 5, with code titles reflective of the exact words of participants. The process of coding, completed by the investigator and project officer who did the interviews, was established through collaborative discussion and ongoing review. Continuous sharing and agreement about the coding occurred throughout the process. After the completion of the coding, the list of code titles was transferred to a Microsoft Word® document and thematically analyzed by the investigator. The following findings are from the codes on the topic of the stress of being separated from family and the consequent desire to be treated locally.

Findings

Reasons for Relocation

The patients in the study had to relocate to metropolitan hospitals for a number of clinical reasons, including to access specialist expertise for diagnostic testing, to undergo chemotherapy treatments (intensive and maintenance), to receive administration of blood products (e.g., immunoglobulin) and transfusions, to undergo stem cell harvest or transplantation (including stem cell, autologous, and allogeneic), to receive specialist and biopsy surgery, and to have access to positron-emission tomography scans.

Emotional Vulnerability

At the point of diagnosis and along the continuum of treatment, the experience of relocation for specialist care was associated with psychosocial stress. Because the testing and confirmation of diagnosis are conducted at metropolitan hospitals, patients initially leave home in a state of worry and uncertainty, unprepared for the experience of dealing with a life-threatening condition in a metropolitan center away from the comfort of their family and community. Commonly, patients are uncertain of their diagnosis, how long they will be away, and what treatment will be required. Patients can feel a sense of immediacy, with only hours from the time of referral from the local area to arrival at the metropolitan hospital. According to one participant, “Everything happened so quick; hop into a plane and out of a plane and back into another one and then into [operating room].” Another said, “I suppose everything was moving so fast.”

For some, the initial trip was undertaken with the added stress of experiencing a serious illness with accompanying pain and discomfort. According to one participant, “I got sick so I ended up in the emergency service at [the regional hospital and] sent to Brisbane.” Another said, “I got really sick, really sick. And then I had to fly to Brisbane early because I was in bad trouble.”

A major issue for many who relocated was the sense of disorientation and being overwhelmed by the speed and complexity of the city. All patients will experience shock at diagnosis and relapse, but those who relocate must deal with this away from the comfort of home and family. In a state of shock, many have to navigate traffic routes that are unfamiliar and daunting. One participant said, “I have never driven there, and at times it was very daunting as well.” Another said, “And country people—the traffic terrifies them.” According to one participant, “Oh, for me, I was just a fish out of water because I don’t like cities and I don’t like crowds, and, well, I’m just a ‘bushie.’” Another said, “For someone who hasn’t been to [the city] much, it would be a huge shock.”

When the diagnosis was confirmed, the patients and their families had to deal with the major shock of a life-threatening illness. According to one participant, “Yeah, never even heard of [the disease], and that was the biggest shock to the system.” Another said, “Well, apart from the shell shock. . . . ”

Relapse, like initial diagnosis, can be associated with a sense of shock and confusion. According to one participant, “It was a shock because, after the first relapse, [I] had to have stem cell transplant. And I went, ‘What does that mean?’ That means being in the hospital in [the city] and, yeah, I was shocked.”

The clinical outcome for most patients, whether initial diagnosis or relapse, was to immediately start treatment in a town away from home and, often, in an unfamiliar geographic location. Treatments for hematologic malignancies can be intensive and aggressive, involving such modalities as high-dose chemotherapy and transplantation. The treatments can extend over months, with recovery taking years. Routine follow-up for hematologic treatment is ongoing, usually for the life of the patient. For many, they will experience a cycle of relapse and additional treatments with ongoing monitoring. Relocation for specialist treatment requires that the patient deal with such treatment and follow-up away from the comfort of home and family. As one participant summed up the experience of relocation, “Emotionally, it is just an emotional drain.”

In the state of emotional stress, patients are reliant on family members for emotional and practical support. One participant said, “I suppose my wife handled most of this, and I was sort of, like, not so much, like, in a daze but shell shocked basically. And my partner took care of most of it for me.”

Separation From Family and Home

Although patients have strong emotional and practical needs that require support from family during relocation for specialist treatment, these needs are not always addressed for patients from regional, rural, and remote areas. Long distances between home and the metropolitan hospital can prevent the possibility of daily return trips. Consequently, family members with inescapable responsibilities (e.g., the care of children and older adults, employment commitments) were unable to negotiate the required “time out” to be with the patients in the metropolitan hospital. For patients, the separation from home and family was described as the “biggest” issue creating distress. According to one participant, “It is so hard. That is a huge distance between your family and treatment.” Another said, “Just being alone away from my family was just the hardest bit.”

The distress was not only associated with lack of support and loneliness for patients, but also was related to concerns about the impact of separation on family members remaining at home. The distress was particularly acute for patients who were parents because they had to cope with the emotional turmoil of leaving their children and the worry about the impact of their absence on the children’s emotional and practical well-being.

Many examples were seen of family members taking responsibility for continuing the running of the home in the patients’ absence, including the maintenance of the home, care of the children, and care of pets. Some families were able to organize to take over responsibilities at home so the carer could go with the patient or roster family members to take turns to visit the patient in the metropolitan hospital. According to one participant, “We had children at home. . . . Luckily, we have tremendously supportive family.”

However, the lengthy periods of time required for treatment can be a barrier to sustaining such support, which can result in patients undergoing treatment alone.

My family came for the first six to eight weeks. But they all had to go back to work, so they used to come and see me when they could, so I was mostly there by myself. Yes, for about four months.

Distance was not only a barrier to family members coming to the metropolitan area, but also to patients returning home, even for short breaks from the treatment experience. One participant said, “Just the sheer distance away, eight hours, and it’s just not possible to get home.” Another participant said, “It was very heavy duty, and it was that I couldn’t get to come home at all.”

Strong Desire to Return Home

A strong theme for those who had to relocate for specialist treatment was the sense of being “stuck in the city” without a choice, accompanied by a longing for the rural setting.

We are out in the country, and it is a real shock to the system when you get stuck in the city, and they give you the questionnaires at the hospital when you are admitted, and they say if you still like to do the things you are doing. And I wrote on it, “No, my fishing line will not reach the water from here” [laughs]. I can’t see my cattle.

The comparison is made to metropolitan patients who have the choice to return home when able because distance is not a problem. According to one participant, “It would have been alright if I’d lived in [the city] because once you get out of the hospital, you can just go home.”

Particularly for those who had to relocate alone, a sense of loneliness can be associated with undergoing treatment away from home and family. According to one participant, “I was isolated from people up here, and family weren’t living in the area, so they couldn’t come, and that was all very difficult.”

The loneliness and homesickness in patients were exacerbated by the fact that the illness, tests, and treatments left the patients tired and wanting the comforts of home. The stress was heightened by the lengthy times spent in the hospital.

Oh, it’s emotional, you think you can never get home. You almost sit there and think, “Am I ever going to go back to my home?” You are so ill. I hated being down there; I’m not going to lie. I hated the whole process in [the city].

The opportunity to return home was greatly valued and the experience of returning described as positive and pleasurable. One participant said, “That’s right. That’s right. We couldn’t get back home fast enough . . . such a nice thing to be able to go home.” Although the patients had to drive long distances, returning home whenever possible was seen as important because it was considered nourishing and provided many benefits.

I had always stuck with the idea of wanting to spend as much time at home. It takes a bit of driving, but, to me, having a few days on the beach here is, like, [so good]. . . . So we would go home and spend time getting what we could out of that. Once I got out of the woods with a cycle, I came home.

Many patients would drive for many hours to be able to return home. One participant who lived 3 hours and 20 minutes from the city hospital said, “I come home, and then a couple of days later I’ve got to go down for more chemotherapy.” According to another participant,

It’s a five-hour drive. . . . I was tripping down there and staying the night in a motel and tripping back. And some days, if I felt really, really good, I would go and come back in the same day. I spent six hours waiting in the waiting room and go in for a two-minute appointment. I’m getting to the stage now where I’m getting sick of driving.

A stoicism is associated with rural living, which could translate into individuals not talking about their longing to go home. One participant said, “My dad is an old bushie and he just told me, like, ‘It doesn’t matter how far it is or what you’ve got to do, you just got to go.’ So I never whined or complained.”

For those who did talk about their feelings, some indicated that the longing for home was not always understood. One participant said, “A lot of them couldn’t understand why I wanted to go home. . . . They said, ‘Why do you want to go home for?’ You know.” According to another participant,

A lot of people don’t realize. Like, it’s hard enough getting the treatment, but having the treatment when you’re not at home is a really big thing. If you are sick, you got to go and have the treatment done. And I said, “How would you like it if I said to you that you’ve got to pack your bag and go and live in Victoria for, say, eight months and not see your family.” And I said, “Well, that’s what was said to me.” If I don’t go to [the city], I’m going to die. And I have to go and, like, my family doesn’t really know what’s going on, and I don’t really know what’s going on, you know, whether I’m going to get through it and whatever. And that I think a lot of people don’t understand that part of it.

Many would prefer the option of accessing treatment locally. The experience of being at home during treatment was described as physically and emotionally important. According to one participant, “Yes, not just physically with regard to the travel but emotionally and mentally. The more time you can spend at home, it really boosts your morale and drive to get better sort of thing.” Therefore, many individuals would prefer to be treated locally if that were an option. One participant said, “[To have treatment locally so could stay home] . . . that would be great [laughs]! That would be great. It would be great, but that is the way it didn’t pan out.” According to another participant,

Immensely, yes [would prefer to be treated locally]. Yes, it is such a comfort to be in your own bed, in your own environment. Not 400 km away from your support network. It was just great to be at home during treatment. . . . Yes, that would be the most important thing . . . to spend as much time at home and with your support group that you can.

Discussion

Because of the limited number of cancer services in rural areas, most patients are required to travel significant distances to access cancer care (Butow et al., 2012; McGrath, 1999; Zucca, Boyes, Girgis, & Hall, 2009). The findings indicate that relocation for specialist treatment happens at a time when patients are emotionally vulnerable from the shock of diagnosis or relapse and the confrontation with a potentially life-threatening condition. During this period, when patients experience a heightened need for the comfort and support of home and family, they have to separate from loved ones and travel to metropolitan specialist centers. For many who are not familiar with the metropolitan location, the city can be an alienating and daunting place. For those from regional, rural, and remote locations that are lengthy distances from the metropolitan hospitals, the choice to return home is not a realistic option. Many of the treatments for hematologic cancer are aggressive (e.g., high-dose chemotherapy and transplantation) and lengthy (de la Morena & Gatti, 2011). Therefore, patients can have a sense of being trapped in the metropolitan hospital, undergoing invasive treatments that can extend over lengthy periods of time and being unable to return home. Distance and the length of treatment can be barriers that prevent family and friends from visiting the hospital to provide support. For many, loneliness, which is a significant psychosocial concern for individuals with cancer (Sahin & Tan, 2012), can be an ever-present reality. Research by Deckx, van den Akker, and Buntinx (2014) demonstrated that lack of psychological or social support was an important factor contributing to loneliness.

A tendency for self-sufficiency, a stoicism and resistance to asking for help, has been documented as a characteristic of rural patients (Butow et al., 2012; Clavarino, Lowe, Carmont, & Balanda 2002; Martin-McDonald, Rogers-Clark, Hegney, McCarthy, & Pearce, 2003 ). The findings reported in this article indicate that patients can have a longing to return home, which, because of the stoicism associated with rural living, may not be shared with treating staff. Even for those who share the feelings of loneliness and longing to be home, they may not be understood. Because of the stresses associated with relocation for specialist care, many patients from regional, rural, and remote areas would prefer to be treated locally. The seriousness of this desire to remain at home is indicated by research demonstrating that some patients with cancer will decline treatment because of the time needed to be taken away from family and home to access treatment (Zucca et al., 2009).

Implications for Nursing

Oncology nurses engage in a wide range of roles and settings with patients and their families who have to relocate for specialist treatment. For some, the role specifically is focused on the provision of supportive care (e.g., providing counseling, organizing educational activities, running support groups). Many are directly involved with supportive care organizations providing accommodation and travel support for patients who have to relocate. The majority are involved in the provision of clinical care in a diversity of settings that range from local rural hospitals to major metropolitan oncology wards. Nurses provide frontline contact to patients and are well placed to provide assistance with issues associated with relocation.

According to Gunn, Turnbull, McWha, Davies, and Olver (2013), rural patients with cancer want their unique needs to be acknowledged and responded to differently than their urban counterparts. From the point of diagnosis, patients who have to relocate will require a wealth of practical information (e.g., information about the location and availability of accommodation in the metropolitan area; details about hospital parking, metropolitan transport, and local shopping). As the findings indicate, individuals relocating are likely to be overwhelmed and feel a sense of alienation and confusion in the metropolitan environment. Practical information assists with adjustment to the urban setting.

In addition to practical information, patients will require emotional support. Baer and Weinstein (2013) indicated that nurses can have a direct and positive impact on the care of patients and their family through therapeutic communication. The findings indicate that, although stoicism inhibited some from seeking support, others did share their stories and were not understood. This article makes a contribution to the emerging literature on relocation for specialist treatment, which provides nurses with detailed information on the psychosocial experience associated with leaving family and home to receive treatment in a metropolitan area. The research findings can help to inform nurses’ discussions with patients about the experience of relocation in a way that affirms the patients’ difficulties and acknowledges the need for assistance. McLeod et al. (2010) demonstrated that the sense of being known by the nurse was identified by families as helpful for negotiating the cancer experience. When necessary, nurses can be a source of referral to additional supportive care.

For many reasons, patients living in rural and remote areas have significantly lower survival rates compared to patients living in metropolitan locations (Butow et al., 2012; Coory, Ho, & Jordan, 2013). The barrier of distance to treatment and the limited resources for oncology service delivery in rural and remote areas contribute to the situation (Paul, Hall, Carey, Cameron, & Clinton-McHarg, 2013). Consequently, in recent years, innovative structural or health system initiatives that can help to alleviate the disadvantage associated with living in locations that are distant from specialist centers have been explored. Coory et al. (2013) detailed a number of solutions that include the implementation of various forms of specialist outreach (e.g., shared care, telehealth, “fly-in, fly-out” health services, virtual multidisciplinary teams) and strengthening capacity in regional cancer centers. The international sharing of ideas about strategies and model development can facilitate change in this area. Outreach programs, shared care, and telehealth as initiatives for long-term improvement in health outcomes for rural and remote communities are used and promoted in Australia, Canada, and Scotland (Adams et al., 2009). Such strategies have been shown to provide equitable access and increase use rates among patients (Adams et al., 2009). The health policy and systems development associated with such initiatives is an exciting area for nurses to demonstrate leadership. Nursing research, knowledge, understanding, and scholarship can be used to respond at a systemic level to the plight of patients with hematologic malignancies who are stressed by the experience of relocation and prefer to obtain treatment locally.

Conclusion

This article provides a description of relocation for specialist treatment from the perspectives of patients with hematologic cancer who are stressed by having to leave their family and would prefer to undergo treatment locally. The author hopes that the findings can be used to inform nursing practice in a diversity of areas, including supportive care, clinical practice, and health policy leadership.

The author gratefully acknowledges Bill Petch, chief executive officer of the Leukaemia Foundation of Queensland (LFQ), Barbara Hartigan, director of LFQ support services, Maryanne Skarparis, LFQ support services coordinator, Kathryn Huntley, LFQ support services coordinator, and Nicole Rawson, research officer at Griffith University in Queensland, Australia, for their contribution to the study.

References

Adams, P., Hardwick, J., Embree, V., Sinclair, S., Conn, B., & Bishop, J. (2009). Literature review: Models of cancer service for rural and remote communities. Retrieved from http://cancerinstitute.org.au/media/70218/web09-83-02_literature_review…

Baer, L., & Weinstein, E. (2013). Improving oncology nurses’ communication skills for difficult conversations [Online exclusive]. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17, E45–E51. doi:10.1188/13.CJON.E45-E51

Bilotti, E., Faiman, B.M., Richards, T.A., Tariman, J.D., Miceli, T.S., & Rome, S.I. (2011). Survivorship care guidelines for patients living with multiple myeloma: Consensus statements of the International Myeloma Foundation Nurse Leadership Board. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 15(Suppl.), 5–8. doi:10.1188/11.S1.CJON.5-8

Brundisini, F., Giacomini, M., DeJean, D., Vanstone, M., Winsor, S., & Smith A. (2013). Chronic disease patients’ experiences with accessing health care in rural and remote areas: A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series, 13(15), 1–33.

Butow, P.N., Philips, F., Schweder, J., White, K., Underhill, C., & Goldstein, D. (2012). Psychosocial well-being and supportive care needs of cancer patients living in urban and rural/regional areas: A systematic review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20, 1–22. doi:10.1007/s00520-011-1270-1

Clavarino, A.M., Lowe, J.B., Carmont, S.A., & Balanda, K. (2002). The needs of cancer patients and their families from rural and remote areas of Queensland. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 10, 188–195. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1584.2002.00436.x

Coory, M.D., Ho, T., & Jordan, S.J. (2013). Australia is continuing to make progress against cancer, but the regional and remote disadvantage remains. Medical Journal of Australia, 199, 605–608. doi:10.5694/mja13.10055

Deckx, L., van den Akker, M., & Buntinx, F. (2014). Risk factors for loneliness in patients with cancer: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 18, 466–477. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2014.05.002

de la Morena, M.T., & Gatti, R.A. (2011). A history of bone marrow transplantation. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America, 25, 1–15. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2010.11.001

Given, B.A., & Northouse, L. (2011). Who cares for family caregivers of patients with cancer? Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 15, 451–452. doi:10.1188/11.CJON.451-452

Grant, M., & Ferrell, B. (2012). Nursing role implications for family caregiving. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 28, 279–282. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2012.09.011

Gunn, K., Turnbull, D., McWha, J.L., Davies, M., & Olver, I. (2013). Psychosocial service use: A qualitative exploration from the perspective of rural Australian cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21, 2547–2555. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1812-9

Hassan, M., & Abedi-Valugerdi, M. (2014). Hematologic malignancies in elderly patients. Haematologica, 99, 1124–1127. doi:10.3324/haematol.2014.107557

Jemal, A., Siegel, R., Xu, J., & Ward, E. (2010). Cancer statistics, 2010. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 60, 277–300. doi:10.3322/caac.20073

Martin-McDonald, K., Rogers-Clark, C., Hegney, D., McCarthy, A., & Pearce, S. (2003). Experiences of regional and rural people with cancer being treated with radiotherapy in a metropolitan centre. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 9, 176–182. doi:10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00421.x

Mayan, M.J. (2009). Essentials of qualitative inquiry. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

McGrath, P. (1998). Relocation for treatment for leukaemia: A description of need. Australian Health Review, 21, 143–154.

McGrath, P. (1999). Experience of relocation for specialist treatment for haematological malignancies. Cancer Strategy, 1, 157–163.

McGrath, P. (2012). The impact on sexuality after diagnosis and treatment for a hematologic malignancy: Findings from Australia. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39, 595–600. doi:10.1188/12.ONF.595-600

McGrath, P., & Holewa, H. (2007). Special considerations for haematology patients in relation to end-of-life care: Australian findings. European Journal of Cancer Care, 16, 164–171. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00745.x

McGrath, P., Holewa, H., & Etcheverry, P. (2011). Surviving the crisis of relocation for specialist treatment in haematology: Insights from New Zealand. Illness, Crisis, and Loss, 19, 233–247. doi:10.2190/IL.19.3.c

McLeod, D.L., Tapp, D.M., Moules, N.J., & Campbell, M.E. (2010). Knowing the family: Interpretations of family nursing in oncology and palliative care. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 14, 93–100. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2009.09.006

Paul, C.L., Hall, A.E., Carey, M.L., Cameron, E.C., & Clinton-McHarg, T. (2013). Access to care and impact of cancer on daily life: Do they differ from metropolitan versus regional haematological cancer survivors? Journal of Rural Health, 29(Suppl.), s43–s50. doi:10.1111/jrh.12020

Payne, S., Jarrett, N., & Jeffs, D. (2000). The impact of travel on cancer patients’ experiences of treatment: A literature review. European Journal of Cancer Care, 9, 197–203. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2354.2000.00225.x

Rodriguez-Abreu, D., Bordoni, A., & Zucca, E. (2007). Epidemiology of hematological malignancies. Annals of Oncology, 18(Suppl.), i3–i8. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdl443

Sahin, Z.A., & Tan, M. (2012). Loneliness, depression, and social support of patients with cancer and their caregivers. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 16, 145–149. doi:10.1188/12.CJON.145-149

Sant, M., Allemani, C., Tereanu, C., De Angelis, R., Capocaccia, R., Visser, O., . . . Berrino, F. (2010). Incidence of hematologic malignancies in Europe by morphologic subtype: Results of the HAEMACARE project. Blood, 116, 3724–3734. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-05-282632

Zucca, A., Boyes, A., Girgis, A., & Hall, A. (2009). Travel all over the countryside: Travelling for cancer treatment in NSW and Victoria. Asia-Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology, 5(Suppl. 2), A262.

About the Author(s)

Pam McGrath, B.Soc.Wk., MA, PhD, is an associate professor and a senior research fellow in the Centre for Community Science in Griffith Health Institute at Griffith University in Meadowbrook, Queensland, Australia. Funding for the research was provided by the Leukaemia Foundation of Queensland. McGrath can be reached at pmcgrathgu@gmail.com, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted November 2014. Accepted for publication January 6, 2015.)