Patient Perceptions of Survivorship Care Plans: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation

Purpose: To understand the perceptions of patients with cancer regarding the role and purpose of a survivorship care plan (SCP) to inform content and delivery opportunities.

Participants & Setting: A mixed-methods evaluation was conducted among patients at a survivorship clinic for high-risk survivors of sarcomas in an academic medical center.

Methodologic Approach: An electronic survey was administered, followed by qualitative telephone interviews.

Findings: 51 surveys were delivered, and 23 surveys were completed. Eight telephone interviews were completed. Content analysis revealed that participants value the SCP as a health management tool to address information needs and reduce fear of recurrence. Few participants shared their SCP with other healthcare providers.

Implications for Nursing: Patients use their SCP as a health management tool to understand the details of their cancer history and treatment and to manage their health concerns. Nurses who care for patients with cancer are well positioned to use the SCP as a patient education tool.

Jump to a section

The number of cancer survivors is steadily increasing, with an expected 18 million cancer survivors in the United States by 2022 (Siegel, Miller, & Jemal, 2017). Some cancer survivors are at an increased risk for developing multiple chronic diseases, which has been characterized as premature aging (Gibson et al., 2018; Ness et al., 2018). As the survivor population grows, the needs of this heterogeneous population is garnering increased attention (Shay, Parsons, & Vernon, 2017). Multidimensional and complex in nature, cancer survivorship is associated with ongoing medical needs related to the post-treatment effects of cancer therapies, continuous monitoring for recurrence, and numerous other significant psychosocial sequelae surrounding the management of cancer survivorship. In an effort to address these needs, in 2005, the Institute of Medicine recommended all cancer survivors receive an individualized survivorship care plan (SCP) on treatment completion (Hewitt, Greenfield, & Stovall, 2006). SCPs vary but should contain a complete treatment summary, information about treatment-related long-term effects and late effects, recommendations for screening and follow-up care, and recommendations for health maintenance for the patients and their caregivers (Benci et al., 2018). Since this recommendation, SCPs have taken multiple forms—from templates that can be completed by healthcare providers with or without patient involvement to practice-specific SCPs that vary in content, design, and messaging. SCPs are intended to inform cancer survivors and healthcare providers about ongoing needs related to cancer survivorship and facilitate communication among the healthcare providers involved in follow-up care.

Since the 2005 recommendation to implement SCPs to all cancer survivors, cancer programs have struggled to implement SCPs (van de Poll-Franse, Nicolaije, & Ezendam, 2017). One proposed reason is a lack of empirical evidence that supports positive outcomes on patient knowledge or behavior change. Several studies have investigated patient and provider satisfaction with SCPs, with generally positive perceptions of their utility (Brennan, Gormally, Butow, Boyle, & Spillane, 2014; Palmer et al., 2015). Receipt of an SCP has been shown to decrease unmet informational needs about treatment history and risks of late effects among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors (Shay et al., 2017). Although few studies have identified positive perceptions of survivors using SCPs and supported the role of SCPs to meet informational needs (Palmer et al., 2015; Shay et al., 2017), these findings are often preliminary and far from conclusive. In a review of four randomized clinical trials of SCP delivery, only one study (the POSTCARE trial) demonstrated a positive effect on self-reported health outcomes and self-efficacy (Kvale et al., 2016; van de Poll-Franse et al., 2017). Another study by Faul et al. (2014) on the use and effect of SCPs among older adult breast cancer survivors found that receipt of an SCP increased patient knowledge but did not affect patient function. Despite the burgeoning literature on the role of SCPs for cancer survivors, few studies evaluate the effect of SCPs on survivors and their healthcare providers.

A systematic review of the role of SCPs identified 10 eligible studies (five randomized controlled trials) and did not find significant effect of SCPs on survivor distress, satisfaction with cancer care coordination, or oncologic outcomes (Brennan et al., 2014). This systematic review indicated that SCPs have great potential to benefit survivors’ well-being, but it is imperative for future research to focus on the following two areas:

• Assessing patient-reported outcomes (e.g., knowledge development, cancer management behavior) that move beyond their perceptions of the SCP

• Developing and evaluating different strategies so that the purpose of the SCP can be maximized (e.g., how survivors are using the SCP now, how the use of SCPs can be improved)

The use of an SCP is a particularly important topic to study because, despite positive perceptions of SCPs from patients and providers, it is unclear whether they facilitate patient–provider communication. A study by Benci et al. (2018) of the OncoLink SCP tool concluded that few patients report sharing their SCPs with other providers. The purpose of the current study is to examine patient perceptions of SCPs and the role of SCPs in overall health management. Understanding patient perceptions of the role and purpose of the SCP can inform SCP content and delivery opportunities.

Methods

To understand patient perceptions of SCPs, the authors analyzed a sample of patients engaged in long-term survivorship care with a survivorship program specializing in high-risk survivors of bone and soft-tissue sarcoma located at the University of Michigan Rogel Cancer Center in Ann Arbor. Patients received an individualized SCP prepared by the medical oncologist and nurse practitioner after each clinic visit. The SCP contained a summary of the clinic visit, the results of the laboratory tests and chest x-ray or computed tomography scan, date of diagnosis, a treatment history with dates and total doses of chemotherapy and radiation, a description of the late effects the patient is at risk for developing and recommendations to reduce their risk, a schedule of cancer screening, and recommendations for a healthy lifestyle. The SCPs are tailored to each patient and vary in length based on patients’ treatment history, number of recurrences or other cancers, and late effects they are at risk for developing. The SCPs range from five to nine pages in length. SCPs are posted to the patient’s online portal, and a paper copy is mailed. SCPs are also shared with the patient’s healthcare providers.

This study was approved by an institutional review board at the University of Michigan, and informed consent was obtained from all patients. A sequential mixed-methods evaluation using a framework approach was used to facilitate the inclusion of patients’ views and experiences and predetermined objectives (Pope, Ziebland, & Mays, 2000).

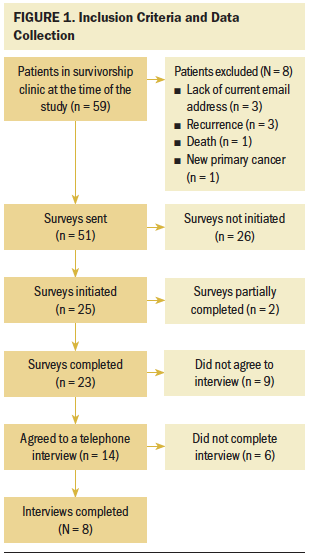

The total number of patients who had completed an initial survivorship clinic visit at the time of the study were included (N = 59). Eight patients were excluded because they did not provide an email address or the email address was invalid, or they were patients who had a recurrence, secondary cancer, or died. Fifty-one patients were recruited to the study via email, which contained a link to an electronic survey. The survey and interview were completed anonymously, and no identifying information was collected. Twenty-five survey responses were received. Two survey responses were incomplete, leaving 23 completed surveys (see Figure 1).

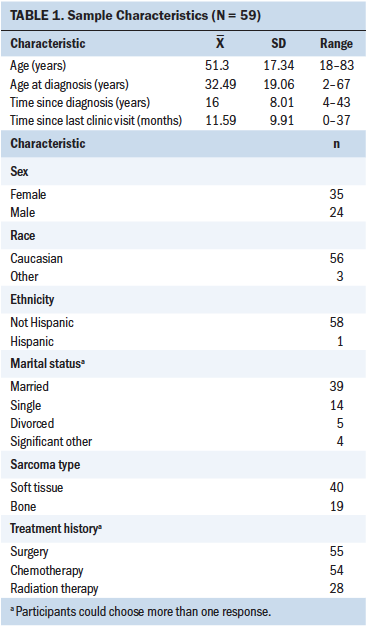

The majority of patients identified as female, married, Caucasian, and non-Hispanic (see Table 1). The demographic characteristics of this clinic were comparable to patient visits to the cancer center overall. Sarcomas can occur at any age but account for 15% of all pediatric cancers (Siegel et al., 2017). Slightly less than half of patients had a sarcoma diagnosed when they were aged younger than 18 years. About half of the patients were aged 18–39 years at the time of the study.

Patients receive an SCP within one week following each annual survivorship clinic visit; therefore, each patient had received an SCP at the time of the study. The date of last visit ranged from 1 to 37 months, with 39 patients’ last survivorship clinic visit being within the past 12 months. Patients were recruited and enrolled from June to August 2018.

The 35-question survey addressed six themes (i.e., information, treatment history, monitoring for recurrence and screening for second cancers, emotion, health, and management) and included closed-ended, multiple-choice questions that were scored on a five-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A detailed review of the survey and responses is available on request to the corresponding author of the current article. Patients were invited to participate in a follow-up qualitative telephone interview by providing a preferred telephone number and best time of contact. Eight qualitative telephone interviews were completed.

Data Analysis

Analysis included descriptive statistics, thematic analysis, and triangulation. The primary outcome variable for the questionnaire is whether patients responded “yes” or “no” to receiving an SCP after their last survivorship clinic visit. Responses were then categorized as receivers (n = 19) and non-receivers (n = 4). Analysis of quantitative results is limited to patients who replied “yes” to the primary outcome variable, indicating they had received an SCP (n = 19) because of the small number of patients who replied “no” to receiving an SCP (n = 4). Frequencies of survey responses were calculated. Likert-type scales were grouped according to domains that were scored on the five-point scale. Cronbach alpha was calculated for consistency and reliability.

Domains include knowledge of treatment history and related health risks, monitoring for recurrence and screening for second cancers, personal health management, informational needs, and emotional response. A combination of positively and negatively worded questions were included to minimize response bias (Sullivan & Artino, 2013).

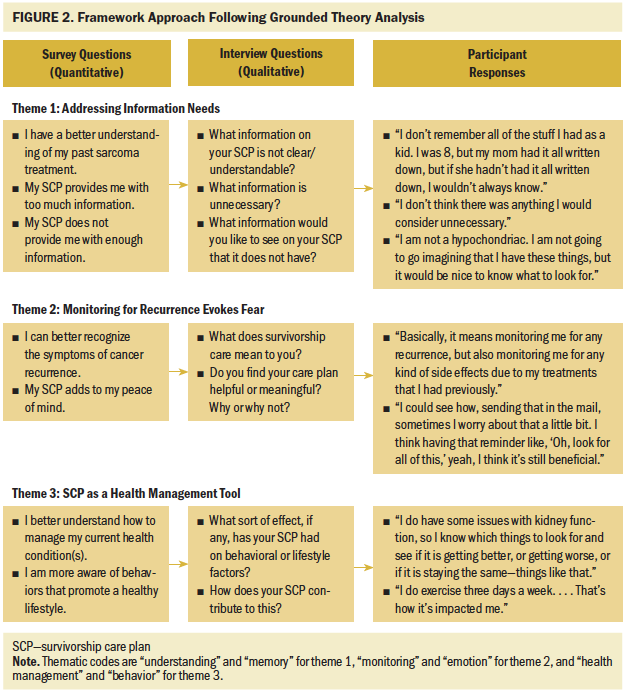

Qualitative data analysis was conducted using grounded theory and thematic content analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Pope et al., 2000) and included respondents who completed a telephone interview (n = 8). Interviews were transcribed and coded by three authors. The qualitative telephone interview consisted of six open-ended questions mirroring the survey question themes, with probes to gain insight, detail, and patient experience. Patients were prompted to share their experiences, in addition to being asked a priori questions. The survey questions were paired with qualitative codes based on the thematic content. For example, the survey questions in the domain of treatment history was paired with qualitative codes “understanding” and “memory” because the meaning of the assigned codes aligned with the content of the survey questions. The survey questions addressed the degree to which the SCP provides information and benefit and were linked to the code “understanding,” which included statements that addressed the degree to which the SCP increased the patient’s understanding of his or her treatment history by providing information. The transcripts were reviewed for concordance, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Coders employed axial mapping to organize similar codes into higher-order categories, which identified themes (O’Cathain, Murphy, & Nicholl, 2010; Pope et al., 2000) (see Figure 2). Quotes may cross domains. Qualitative data were reviewed until saturation was reached. Data saturation is an iterative process and a goal of qualitative research. Interviews lasted 10–15 minutes.

Results

Addressing Information Needs

Patients responded that, because of the SCP, they have a better understanding of their past sarcoma history and treatment, as well as their current test results with regard to monitoring late effects stemming from treatment. They also reported that the SCP was helpful and would be useful in the future. Patients described the experience of treatment as fading over time and that they struggled to remember the details. The treatment summary on the SCP provided a useful overview that patients could refer back to and avoid repeatedly telling their treatment narrative. One patient said the following:

I feel like I have had to tell this story so many times to so many people that, sometimes, I forget details or whatever, so it was nice to have it all there. I could just be like, “There you go.” (Patient 8)

However, patients’ responses were more nuanced with regard to the amount of information provided in the SCP, commenting that the length of the SCP was indicative of the individualized nature of the care plan and reflective of the time invested.

It was really long, but I didn’t see anything wrong with it being that long. I actually thought it was kind of nice, because sometimes you get reports from the doctor and they are, like, a paragraph. This one seemed very in-depth, and it was put into terms that you could understand. You don’t have to go googling every other term. (Patient 3)

Despite the length, patients still sought more detailed information about their current health conditions, particularly related to their past cancer. Many patients commented that they were unsure which, if any, symptoms were related to their treatment history.

I think, for me specifically, like, a list of symptoms [would be helpful]. If you feel this, go see your doctor. I think, for a patient, it is nice to know that. I am, like, 18 years out at this point, so I feel like it’s been a really long time, but sometimes, if you feel things, you are like, “Oh, is that normal, or could that be a side effect of sarcoma?” (Patient 7)

Patients emphasized their desire for clear directives of which symptoms to report and how to recognize when something is wrong. Patients accurately expressed that the most likely region for sarcoma recurrence is the lungs, a region they perceived as not producing recognizable symptoms. Understanding that the annual chest x-ray monitors for recurrence left patients desiring more information, such as the probability of recurrence or symptoms that they could self-monitor. One patient described the intangible nature of possible recurrence as influencing the desire for more information.

Initially, my sarcoma showed itself as a lump, and so I knew right away. Would I know if it came back in my lungs? I don’t know. . . . It is easy to see a soft-tissue sarcoma, just because of the tumor growth. But, like I said, if it metastasized in the lungs, could I spot it? Probably not. I don’t know what the symptoms would be. (Patient 1)

I know that, even if once a year, he is looking at what my blood tests are showing and what is going on with my body. That gives me a high level of comfort. (Patient 2)

Patients described the SCP as providing concrete evidence of their current health status because the SCP included the results of the chest x-ray and blood tests, which enabled them to participate in monitoring their health conditions. One participant described this as follows:

I do have some issues with kidney function, so I know which things to look for and see if it is getting better, or getting worse, or if it is staying the same—things like that. (Patient 1)

The period between annual survivorship visits can be a source of concern for patients, many of whom stressed the importance of the annual chest x-ray to monitor for recurrence as an essential component of their survivorship care. Patients reported that their ability, or lack of ability, to self-monitor for recurrence was an ongoing source of worry based on wanting clear and concrete directives indicative of cancer.

Monitoring for Recurrence Evokes Fear

The SCP includes a screening schedule from the American Cancer Society specified to male or female patients, as well as a recommendation for an annual chest x-ray to monitor for sarcoma recurrence. Each patient’s recommended cancer screening schedule is modified based on additional risk factors, such as family history, which are updated at each annual visit. Patients stated that, for them, survivorship care was synonymous with ongoing monitoring and screening. The SCP includes a list of symptoms to report to a healthcare provider, such as painful swelling of the lymph nodes, weight loss, loss of appetite, and unusual fatigue. Patients were also neutral regarding the SCP enabling them to recognize symptoms of other cancers, repeating the desire for clear, tangible signs or symptoms that they could recognize. One patient described it as follows:

Basically, like I said before, if there was something in the care plan that said, “These are the symptoms to look out for. These are things that could possibly happen. This might be what it feels like if you get a recurrence somewhere,” [that would be helpful]. Like, if it spread to my lungs, I don’t know what to look for. It’s not a bone where I can see it. . . . I could see the tumor in my arm. The other types of cancers to watch out for, I try to watch out for all of them, but I don’t necessarily know the symptoms of them. (Patient 3)

Patients described the annual clinic visit and accompanying SCP as alleviating a sense of worry about recurrence and late effects, responding that the SCP adds peace of mind and positively affects psychological and emotional health. Patients further responded that the SCP did not increase their anxiety or worry, cause them to worry about their quality of life, or make them worry their conditions will get worse. However, patients continued to describe the first clinic visit as eliciting feelings of fear and worry. Although some patients’ fears were alleviated by the clinic visit, others found the visit to be a reminder of the past. One patient described her first survivorship clinic visit as “scary” and wanting to “be an ostrich about it.” She described her feelings after the clinic visit as follows:

What I can say, though, is it was scary. I didn’t want to know, but I should know, and I’m glad I know. . . . I’d love to be an ostrich about it. It really gets you through a lot when you’re sick. I’m healthy now and need to do everything now to stay that way. (Patient 8)

Patients described balancing their perceptions of needing near-constant monitoring with wanting to move past their cancer experience as a source of stress and worry. However, the stress and worry associated with recurrence and the clinic visit diminished with subsequent visits. The SCP is a tool that is a part of this balancing act.

Really, at this point, it’s not important, but I do have children and grandchildren. That would be a question. Is it something I have to think about for them? So, if I had to answer myself, I would say be on the lookout if anything comes out, have that checked. I’m very grateful for my life, if you had a treasure like that, you would refer to it. To refresh. (Patient 8)

Survivorship Care Plan as a Health Management Tool

The SCP improved patients’ understanding of their current health conditions and how to manage those conditions and gave them resources to manage those conditions. Patients’ understanding of their current health was framed in the discussion of how they define quality of life after cancer treatment. Many patients defined their quality of life as recognizing their limitations, concentrating on what they can do rather than what they cannot do. For many, it meant balancing a return to the life they had before cancer with the reality of aging.

Well, within reasonable limits, it means, on a daily basis, being able to do the things that I have always been able to do. My energy level, my physical mobility levels, that they stay pretty constant. I understand that, as I age, they are not going to stay constant; it is just a downhill slide, frankly. (Patient 2)

The SCP improved patients’ feeling of involvement in their health care and capabilities in managing their health overall. In contrast to the lack of confidence patients expressed in their ability to self-monitor for sarcoma recurrence and second cancers, patients’ positive perceptions of their health management focused on the day-to-day behavior they could control, including diet, physical activity, and alcohol consumption. Patients outlined specific behaviors to which they had made adjustments since coming to the clinic, supporting SCPs as health management tools.

I am conscious of what I eat, I am watching sodium and carbs, all of that. I was a good—I want to say healthy—wine drinker. I like my wine, but my liver and everything has been affected. I didn’t realize that before, because I feel fine. On my lab test, it says that we’ll watch for build-up quite a bit. I have lost about 67 pounds, and I feel good. (Patient 6)

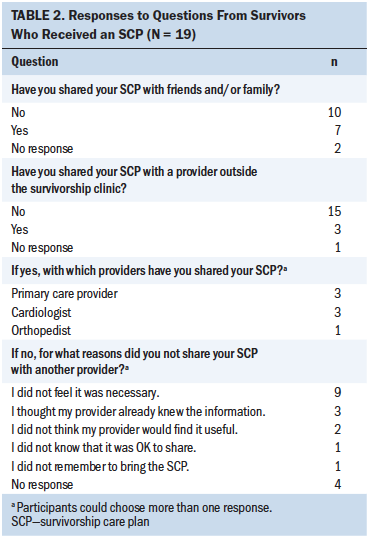

Patients did not differentiate between the SCP and the clinic visit, indicating that the SCP provided a reminder to promote behavior change. One patient said, “It made me say, ‘Well, they are willing to put the effort in, take care of yourself’” (Patient 4). Although the response to the SCP was positive overall, 15 of 19 patients reported that they had not shared their SCP with other providers (see Table 2). Many patients reported that they thought other providers would be receptive to their SCP and that sharing was a good idea, with one patient saying the following:

I like it because I feel like, at my primary care, they don’t even know the things to look for. . . . I can see the benefit of bringing it to my primary care and having a list of my chemos and stuff. (Patient 7)

Absent a directive from the provider to the patient to share the SCP, about half of patients stated that they did not feel it was necessary as the reason for not sharing their SCP with other healthcare providers. Others responded that they forgot their plan, did not know if it was OK to share the plan, or had not seen a provider since receiving their care plan as reasons for not sharing their SCP. However, some responded that they did not think their provider would find it useful or they thought their provider already knew this information. Lastly, others indicated that sharing the SCP with a provider was a good idea, but they had not considered sharing it.

I could see the benefit in a new primary care, just bringing it along and being like, “Hey, this is my past, so now you have all of this information.” I think that would be really helpful. (Patient 7)

One patient indicated that a clear directive in the context of the clinic visit that they could and should share the SCP would be enough to motivate her to share it.

I think that, in [the] clinic, they should just go over, like, “Oh, we are going to send you this. You can take it to your primary care doctor, and make sure you keep it with you in case something happened.” (Patient 7)

Discussion

In contrast to a systematic review of the effect of SCPs by Jacobsen et al. (2018), the current study findings indicate that SCPs can be perceived as useful health management tools that nurses can use to aid patients in understanding their treatment and potential health risks. Patients valued the treatment summary and record of their current laboratory work as a reference tool and expressed that it offered a sense of security. Patients who reported referring back to their SCP most often referenced it in support of efforts to manage their diet and weight. Many of the late effects and comorbid health conditions that occur in high-risk patients (patients who received anthracycline chemotherapy) are at risk for coronary artery disease, lipid disorders, and kidney dysfunction. These risks can be positively influenced by behavioral interventions, including diet modification, weight management, and increased physical activity. The inclusion of an SCP in survivorship care can be an opportunity for patient education and health promotion interventions. This highlights an additional opportunity for nurses to be clear and detailed in their explanations so that patients understand the complete scope of their healthcare team.

The current findings confirm previous research examining factors influencing sharing SCPs with healthcare providers (Benci et al., 2018). Study findings confirm that the majority of patients do not share their SCP with other healthcare providers. However, patients frequently expressed that other healthcare providers would respond positively to the SCP and that it would be a communication tool to enable coordination among their healthcare team. Patients also described enhanced communication among their healthcare providers as desirable and perceived that it would lead to better care. Patients whose health care included communication between the medical oncologist and other healthcare providers (cardiology and primary care) also responded positively.

Perceptions that led to not sharing the SCP included not feeling it was necessary, believing their provider already knew the information, forgetting the SCP, and not knowing or not being told it was something they should or could do. These perceptions could be overcome by the survivorship care team overtly stating that sharing the SCP with other healthcare providers is something patients can and should do.

Other barriers to sharing may be attributable to patients’ emotional response to addressing the long-term and late effects of cancer treatment. The annual screening for second cancers and chronic disease and monitoring for recurrence that accompanies the annual visit produces a mixture of worry, fear, and relief that many patients describe as arising every year with the approaching appointment but lessening with each subsequent visit. Recognizing the potential for this emotional response to annual screening and monitoring, nurses should assess the presence of worry and fear that may lead to avoidance. The desire to remain uninformed with their other healthcare providers also limits the effect of the SCP in addressing the dominant sources of concern expressed by patients, particularly the ongoing fear of recurrence and lack of confidence in self-monitoring for symptoms of a recurrence or secondary cancer. In contrast, patients are more likely to use the SCP as a tool to influence behaviors they control, such as diet and alcohol consumption, and to share those actions with those they perceive to be nonsurvivorship providers, such as nutritionists or mental health providers. The survivorship clinic visit also presented an opportunity for patient education by reviewing the SCP during the visit and highlighting screening and monitoring recommendations. The lack of confidence in self-monitoring further demonstrates a need for an educational plan to teach patients how to use their SCP.

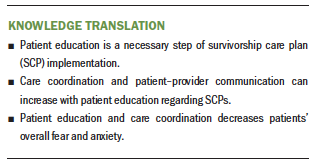

Using the SCP as a tool to increase care coordination and patient–provider communication presents an opportunity to decrease the persistent fear and anxiety reported by patients. Study findings indicate that a lack of confidence in the ability to self-monitor for recurrence and secondary cancers is the primary source of fear, which is confirmed by clinical observations. Emphasizing the role of mental health providers as full partners in their health management and extending care tailored to cancer survivorship will provide additional support to patients, which may affect their desire to remain uninformed.

Limitations

Data were collected as part of a program evaluation, and the study was limited to patients attending the survivorship clinic. The primary goal of the study was to inform content and delivery of the SCP and was delivered anonymously to maximize the response rate. The clinic itself is open to high-risk survivors who have been treated with anthracycline chemotherapy with curative intent and are at least two years past active treatment. Underrepresentation of the clinic population does not invalidate findings of this study because data saturation is an iterative process and the goal of qualitative research. The current research provided insights and opportunities for future exploration. Themes should be validated in a larger representative sample of individuals with cancer to inform SCP design and delivery.

Implications for Nursing

The results of this study demonstrate that patients value their SCP as a health management tool, which they use to understand the details of the cancer history, treatment, and ongoing health management. They experience ongoing fear, anxiety, and worry about recurrence and development of new cancers. Patients emphasized that, although the SCP they received was lengthy, they valued the personalized information it contained and desired additional information on self-monitoring for new cancers and recurrence. The reluctance to share their SCP with other providers provides an opportunity to communicate to patients regarding their role in care coordination and cancer screening. Encouraging patients to take an active role in cancer screening and care coordination, including with mental health providers, may alleviate ongoing fear and anxiety. This demonstrates the capacity for SCPs to act as educational tools for patients with cancer.

Conclusion

The key takeaway from this study is that the SCP is an educational and health management tool that supports clinical care. This study identified opportunities to improve patient–provider communication about care coordination and cancer screening, which may reduce the ongoing fear and anxiety that patients report. Patients desire direct provider communication regarding sharing the SCP to enhance care coordination. Patients also value information that includes clear and actionable steps. Patient education of SCPs is a necessary step of program implementation. Information contained in SCPs is supported by face-to-face clinical discussion and should inform SCP delivery. Nurses who care for patients with cancer are well positioned to use the SCP as a patient education tool, which can enhance care coordination and decrease fear and anxiety.

About the Author(s)

Erin Peregrine Antalis, PhD, MPH, is a senior program manager of the Sarcoma Survivorship Program in the Department of Internal Medicine in the School of Medicine at the University of Michigan; Rylee Doucette, BS, MPH, and Gielle Kuhn, BA, MPH, are MPH graduates of the School of Public Health at the University of Michigan; and Laurence H. Baker, DO, is a collegiate professor of cancer developmental therapeutics and director of the Sarcoma Survivorship Program and Denise Reinke, MS, NP, MBA, is a nurse practitioner in the Sarcoma Survivorship Program, both in the Department of Internal Medicine in the School of Medicine at the University of Michigan, all in Ann Arbor. This study was supported, in part, by the Hope Foundation and the Robert and Heather Urich Research and Patient Care Fund. Antalis, Doucette, Kuhn, and Baker contributed to the conceptualization and design. Antalis, Doucette, Kuhn, and Reinke completed the data collection. Antalis and Doucette provided statistical support. All authors provided the analysis and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Antalis can be reached at erperegr@med.umich.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted November 2018. Accepted February 11, 2019.)

References

Benci, J.L., Vachani, C.C., Bach, C., Arnold-Korzeniowski, K., Hampshire, M.K., Metz, J.M., & Hill-Kayser, C.E. (2018). Identifying barriers to cancer survivors sharing their survivorship care plans with their healthcare provider. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 12, 632-638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-018-0699-3

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101.

Brennan, M.E., Gormally, J.F., Butow, P., Boyle, F.M., & Spillane, A.J. (2014). Survivorship care plans in cancer: A systematic review of care plan outcomes. British Journal of Cancer, 111, 1899–1908. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.505

Faul, L.A., Luta, G., Sheppard, V., Isaacs, C., Cohen, H.J., Muss, H.B., . . . Mandelblatt, J.S. (2014). Associations among survivorship care plans, experiences of survivorship care, and functioning in older breast cancer survivors: CALGB/Alliance 369901. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 8, 627–637. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-014-0371-5

Gibson T.M., Mostoufi-Moab, S., Stratton, K.L., Leisenring, W.M., Barnea, D., Chow, E.J., . . . Oeffinger, K.C. (2018). Temporal patterns in the risk of chronic health conditions in survivors of childhood cancer diagnosed 1970-99: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. Lancet Oncology, 19, 1590–1601. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30537-0

Hewitt, M., Greenfield, S., & Stovall, E. (Eds.). (2006). From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Jacobsen, P.B., DeRosa, A.P., Henderson, T.O., Mayer, D.K., Moskowitz, C.S., Paskett, E.D., & Rowland, J.H. (2018). Systematic review of the impact of cancer survivorship care plans on health outcomes and health care delivery. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 36, 2088–2100. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2018.77.7482

Kvale, E.A., Huang, C.S., Meneses, K.M., Demark-Wahnefried, W., Bae, S., Azuero, C.B., . . . Ritchie, C.S. (2016). Patient-centered support in the survivorship care transition: Outcomes from the Patient-Owned Survivorship Care Plan Intervention. Cancer, 122, 3232–3242.

Ness, K.K., Kirkland, J.L., Gramatges, M.M., Wang, Z., Kundu, M., McCastlain, K., . . . Armstrong, G.T. (2018). Premature physiologic aging as a paradigm for understanding increased risk of adverse health across the lifespan of survivors of childhood cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 36, 2206–2215. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2017.76.7467

O’Cathain, A., Murphy, E., & Nicholl, J. (2010). Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ, 341, c4587. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4587

Palmer, S.C., Stricker, C.T., Panzer, S.L., Arvey, S.A., Baker, K.S., Casillas, J., . . . Jacobs, L.A. (2015). Outcomes and satisfaction after delivery of a breast cancer survivorship care plan: Results of a multicenter trial. Journal of Oncology Practice, 11, e222–e229. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.2014.001404

Pope, C., Ziebland, S., & Mays, N. (2000). Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ, 320, 114–116.

Shay, L.A., Parsons, H.M., & Vernon, S.W. (2017). Survivorship care planning and unmet information and service needs among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology, 6, 327–332. https://doi.org/10.1089/jayao.2016.0053

Siegel, R.L., Miller, K.D., & Jemal, A. (2017). Cancer statistics, 2017. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 67, 7–30. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21387

Sullivan, G.M., & Artino, A.R., Jr. (2013). Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 5, 541–542. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-5-4-18

van de Poll-Franse, L.V., Nicolaije, K.A., & Ezendam, N.P. (2017). The impact of cancer survivorship care plans on patient and health care provider outcomes: A current perspective. Acta Oncologica, 56, 134–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/0284186X.2016.1266080