An Education Intervention to Increase Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Confidence and Acceptability: A Randomized Controlled Trial

Objectives: To explore the effect of an intervention to improve human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination confidence, attitudes, and beliefs among non-Hispanic Black mothers.

Sample & Setting: Participants were 63 non-Hispanic Black mothers of children aged 9–17 years who resided in the United States and whose children had not received HPV vaccination. Interventions and data collection were conducted via a videoconferencing platform.

Methods & Variables: A randomized controlled trial was performed using two groups. The experimental group received two HPV vaccination education sessions and the control group received two healthy nutrition education sessions. Data were collected after the last intervention and four weeks later. Variables included HPV vaccination confidence, attitudes, and beliefs.

Results: The experimental group reported more positive attitudes and beliefs about HPV vaccination (p = 0.002) and greater vaccination confidence than the control group (p = 0.049).

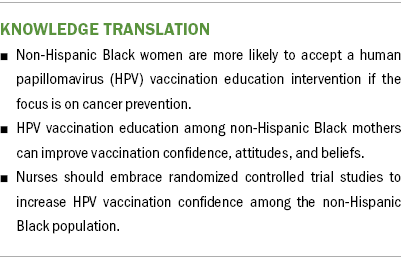

Implications for Nursing: Nurses can improve HPV vaccination confidence, attitudes, and beliefs among non-Hispanic Black mothers through HPV vaccination education.

Jump to a section

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a causative factor in six types of cancer: vaginal, vulvar, cervical, anal, penile, and oropharyngeal. HPV infection is common among men and women (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2020). Every year, about 14 million new cases are reported in the United States, and more than 80% of people will be affected by HPV infection in their lifetime (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2019). The HPV vaccine has effectively prevented HPV-related cancers and genital warts, with a reduction of 86% noted among teen girls and 71% among young adult women, as well as a 40% reduction in cervical precancer among women vaccinated against HPV infection (CDC, 2019). The national completion rate of the three-dose series of HPV vaccines has remained low (51.1% in 2018 and 54.2% in 2019), despite the effectiveness of HPV vaccines (Elam-Evans et al., 2020). Other countries such as Australia have a higher vaccination rate (79%) among girls (Hall et al., 2019). The relatively low rate of vaccination in the United States indicates a need to identify measures to increase parental confidence and intent to vaccinate their adolescent children.

Background

The cancer mortality rate is higher among Black women than in other ethnic and racial groups in the United States (ACS, 2019). Disparities in cervical cancer incidence and mortality rate place Black women in a high-risk population. Non-Hispanic Black women have a 30% higher incidence of cervical cancer than non-Hispanic White women, and the mortality rate of cervical cancer is 80% higher among non-Hispanic Black women than among White women (ACS, 2019).

HPV vaccination is effective in the reduction of precancers and cancers related to HPV. Cervical precancers caused by HPV have decreased by 40% among women who have received the HPV vaccine (CDC, 2019). Despite the effectiveness of the HPV vaccine and the burden of HPV-related cancers, the HPV vaccination rate among Black women is lower than among White women, with a vaccination rate of 45.2% for non-Hispanic Black women compared with 56.5% for non-Hispanic White women in 2018 (Office of Minority Health, 2023).

Limited knowledge of HPV vaccination has been identified as a barrier to HPV vaccination among Black mothers (Cunningham-Erves et al., 2018). Participants with greater knowledge of HPV are more likely to complete the three-dose series of HPV vaccination (Nagpal et al., 2016). A study by Bynum et al. (2011) found that women who reported HPV vaccination uptake had greater knowledge of the HPV vaccine.

Compared with studies addressing multiple races and ethnicities (Cipriano et al., 2018; Dixon et al., 2019), there have been fewer HPV vaccination studies conducted explicitly for Black mothers (Cunningham-Erves et al., 2018; Strohl et al., 2015). A gap in the literature was identified regarding randomized controlled trials. Only four randomized controlled trials were found in a comprehensive literature review on Black mothers’ perceptions of their daughters’ HPV vaccination (DiClemente et al., 2015; Dixon et al., 2019; Joseph et al., 2016; Underwood et al., 2016).

Objectives

The aim of the current study was to explore the effect of an intervention to enhance HPV vaccination confidence, attitudes, and beliefs among non-Hispanic Black mothers. There is limited knowledge of the HPV vaccine, low HPV vaccination confidence, and distrust of healthcare professionals among non-Hispanic Black mothers (Bryer, 2014; Dixon et al., 2019; Hamlish et al., 2012). There are not enough quantitative and randomized trials targeting non-Hispanic Black mothers and HPV vaccination of their preteen and teenaged children. Thus, there was a need for randomized controlled trials designed explicitly for non-Hispanic Black mothers to improve knowledge of HPV and increase vaccination confidence. The authors hypothesized that an education intervention program that highlights the benefits of HPV vaccination as a method of cancer prevention and addresses barriers related to HPV vaccination could improve parental vaccination confidence, attitudes, and beliefs among this high-risk population.

Theoretical and Conceptual Framework

The study was designed using the Health Belief Model (HBM) conceptual framework, derived from the psychological and behavioral theory based on the work of Rosenstock et al. (1988). The model asserts that when a person believes they are susceptible to a disease that has severe outcomes, the individual will more likely conclude that the benefits of preventing the health problem outweigh the barriers associated with behavior change (Rosenstock et al., 1988). The model was proposed to guide parental perceptions of vaccination and identify primary preventive behavior related to disease prevention and screening.

The use of HBM as a framework for cancer prevention is significant in identifying individuals’ motivations and beliefs related to participation in cancer prevention initiatives such as HPV vaccination for preteens and teens. The clinical benefits of vaccinating boys and girls against HPV are significant and include reductions in the risk of cervical, vaginal, oropharyngeal, penile, and other HPV-related cancers (Cassidy et al., 2014). The HBM has six constructs that were used to guide the research study, which are as follows: (a) perceived susceptibility, (b) perceived severity, (c) perceived benefits, (d) perceived barriers, (e) cues to action, and (f) self-efficacy.

In the context of HPV vaccination, perceived susceptibility relates to the perception of the possibility of being infected by the HPV virus. Perceived severity relates to the perception of how bad a condition like cancer will be without HPV vaccination. Perceived benefit is the belief in the vaccine’s efficacy in reducing cancer risk. Perceived barriers are obstacles to HPV vaccination, which include cost, access, transportation, and side effects. Cues to action are prompts that trigger an action, such as strategies to activate vaccination readiness. Self-efficacy is the confidence in one’s ability to perform an action such as having one’s children vaccinated against HPV. The HBM is suitable for this study because it provides a framework for guiding parental perceptions regarding the vaccination of children.

Literature Review

A comprehensive literature review was performed to examine factors related to maternal perception of HPV vaccination among Black women. The review was conducted by searching literature in the PubMed®, CINAHL®, ScienceDirect, Ovid MEDLINE®, and ProQuest databases. The search was limited to studies conducted in the United States and published since the inception of the HPV vaccine in 2006. The factors identified in the review that affected Black mothers’ decisions regarding their children’s HPV vaccination were summarized in five groups: approval and disapproval of HPV vaccination from doctors, family, and friends; knowledge of HPV and HPV vaccination; attitudes and beliefs regarding HPV vaccination; the benefits of the HPV vaccine; and challenges and barriers to HPV vaccination.

Approval and Disapproval of HPV Vaccination From Doctors, Family, and Friends

Most Black mothers trusted their physicians to start the discussion of HPV immunization of their children (Hamlish et al., 2012). A study by Thompson et al. (2011) showed that adolescent vaccination status significantly depends on the provider’s recommendation of a vaccine (p < 0.001). In one study, most mothers indicated that provider recommendation influenced their decision to vaccinate their daughters against HPV (Thompson et al., 2012). A study by Joseph et al. (2016) found that most participants would accept HPV vaccination if recommended by their provider. Provider approval of HPV vaccination is independently associated with vaccination against HPV infection (Gottlieb et al., 2009).

Suggestions and recommendations from family members, friends, and physicians predict mothers’ HPV vaccination intentions (p = 0.001) (Cunningham-Erves et al., 2018). Most mothers trusted suggestions from family and friends regarding HPV vaccination. Mothers with high exposure to individuals with anti–HPV vaccine perspectives and low exposure to pro–HPV vaccine individuals have a higher HPV vaccine refusal rate (Fu et al., 2019). Griffioen et al. (2012) found that mothers’ HPV vaccination uptake was associated with communications between family, friends, and clinicians, as well as media reports.

Knowledge of HPV and HPV Vaccination

A study by Cipriano et al. (2018) found a positive relationship between knowledge of HPV and maternal attitudes to vaccination. HPV vaccination education predicts vaccine uptake. Children of mothers who have received HPV vaccine education are three times more likely to receive a dose of the HPV vaccine (p = 0.003) (Dixon et al., 2019). A study by Gottlieb et al. (2009) indicated knowledge deficit and lack of HPV vaccine information as factors affecting the initiation of HPV vaccination. Most mothers who reported increased HPV vaccine uptake showed higher knowledge of the HPV vaccine (Bynum et al., 2011). Children of mothers with a better understanding of HPV vaccination are more likely to complete the three doses of the HPV vaccine than those with moderate to low knowledge (Nagpal et al., 2016). Watkins et al. (2015) found that women who have a history of cancer, are less spiritual, and have higher education, as well as younger people, had better knowledge of HPV vaccination.

Attitudes and Beliefs

A study by Galbraith-Gyan et al. (2019b) found that participants with positive attitudes regarding HPV vaccination better understand the benefits of cancer and infectious disease prevention. A study by DiClemente et al. (2015) reported that children received the HPV vaccine if their mothers thought they were at risk of HPV infection and cervical cancer. Experiences and beliefs affect mothers’ decisions to vaccinate their daughters against HPV (Griffioen et al., 2012). A study by Bryer (2014) reported a relationship between vaccine beliefs and attitudes. Attitudes influence vaccine intention. A study by Galbraith-Gyan et al. (2019b) identified the following reasons for mothers’ negative attitudes toward the HPV vaccine: The vaccine was not one-size-fits-all, their daughters were too young to receive the vaccine, and the vaccine was new. The significant predictor of maternal HPV vaccination intention was the belief about susceptibility to an HPV infection (p = 0.044) (Cunningham-Erves et al., 2018).

Perceived Benefits of HPV Vaccination

Mothers need to understand the benefits of HPV vaccination to decide for or against vaccinating their daughters. A study by Read et al. (2010) showed that mothers’ and daughters’ acceptance of HPV vaccination is significantly related to their understanding of the HPV vaccine as a cancer prevention vaccine (p < 0.001). Recognition of the HPV vaccine as a cancer prevention vaccine has been identified as a predictor of mothers’ decisions to vaccinate their daughters (Perkins et al., 2010). In a study to determine HPV vaccine beliefs of Black mothers and daughters, Galbraith-Gyan et al. (2019a) found that mothers and daughters tended to believe in the benefits of the HPV vaccine against cervical cancer and genital warts. Nan et al. (2016) found that most mothers believed the long-term benefits of HPV vaccination outweighed the current cost of vaccination (Nan et al., 2016).

Challenges and Barriers to HPV Vaccination

A study by Galbraith-Gyan et al. (2019a) showed that the vaccine’s unknown side effects and safety, as well as policies and politics, are barriers to HPV vaccination among mothers and daughters. Thompson et al. (2012) identified the following factors affecting Black mothers’ HPV vaccination uptake: vaccine cost, attitudes regarding the vaccine, fear of sexual activity at an early age, and lack of insurance. Black individuals are less likely to start HPV vaccination than White individuals (p < 0.001) (Gelman et al., 2013), indicating racial and ethnic disparities in HPV vaccination.

Summary of Findings

Understanding factors associated with Black mothers’ decision to vaccinate their children is vital. This knowledge would enable providers and healthcare professionals to develop strategies to increase HPV vaccination uptake among this high-risk population.

Methods

Study Design

The current study was a randomized controlled trial with a two-group design consisting of HPV vaccination education for the experimental group and healthy nutrition education for the control group. The HPV vaccination and healthy nutrition education programs were conducted during two one-hour sessions that occurred one week apart. The intervention’s effectiveness was assessed immediately following the second intervention and four weeks post–second intervention. Participants were randomized into the experimental group and control group. Data were collected via the Zoom online videoconferencing platform using a survey link from PsychData. The virtual education sessions were presented via Zoom, and a meeting link with a password was sent to the participants’ emails. The main research variables were the HPV vaccination education intervention (independent variable) and the Vaccination Confidence Scale (VCS) and Carolina HPV Immunization Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (CHIAS) scores (dependent variables).

Setting

Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the study setting was virtual, and the authors used the Zoom videoconferencing platform for the intervention and data collection. The online environment eliminated on-site social gatherings as a precaution against COVID-19 and broadened the research study’s scope by providing the opportunity to reach more participants virtually.

Protection of Human Subjects

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the institutional review board at Texas Woman’s University in Houston. Participants were screened using the eligibility criteria form. The institutional review board reviewed, approved, and stamped the study’s informed consent. Consent forms were sent to eligible participants via email, which they signed and returned through DocuSign using an electronic signature. DocuSign features prompted participants to complete the electronic consent form; apply electronic signatures, initials, and dates; and then click the send button to return the document. The participants did not need to print or download a copy of the consent form.

The study’s consent form had a detailed explanation of the research process, such as the study’s length, the research study’s onset, the expected end of the study, the number of education sessions, and the number of times the survey would be given. Participants were informed of their right to stop participating at any time during the study. Participants’ privacy was maintained: No identifying information was collected in the survey, and the researcher coded the survey forms before the data collection. Participants were informed of the study’s potential risks, and steps to minimize the risks were explained. Explicit instructions were given to participants on how to contact the researchers. A researcher’s email address and telephone number were available to the participants. Alternate contact information for the study chairs was available to the participants if they could not reach the researcher at any time. Any concerns about participants’ rights would be forwarded to the Texas Woman’s University’s Office of Research and Sponsored Programs.

Sample

The power analysis was calculated using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) at two time points. The number of participants required for the study was determined using an effect size of 0.25 (f) in repeated measures ANOVA (two groups at two time points). An 80% power with an alpha of 0.05 yields a total sample size of 46 mothers (23 in each group). A sample of 54 participants was recruited at the study’s beginning considering a 15% attrition rate. The current effect size was used because there were no relevant earlier findings on the topic. Therefore, the researchers used conventions based on expectations of a small to moderate effect. A literature search performed by the researchers, with the assistance of librarians from Texas Woman’s University, did not yield any randomized controlled trial with mean and SD data on the topic needed to calculate the effect size. Criteria for eligibility were as follows: (a) non-Hispanic Black mothers of children aged 9–17 years who had not been vaccinated against HPV, (b) aged 18 years or older, (c) able to speak and write English, and (d) residing in the United States.

Recruitment

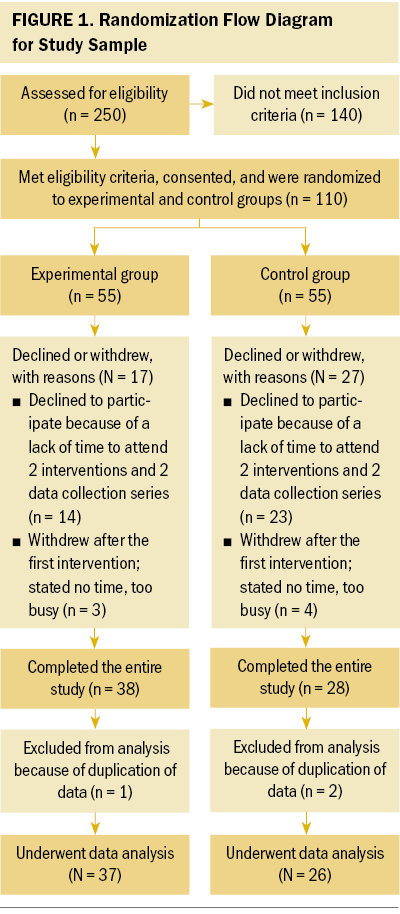

Eligible participants were recruited through social media (Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn) by networking with professional organizations, community centers, health clinics, and churches with predominantly non-Hispanic Black individuals in the United States. Some participants were recruited through snowball sampling strategies. Study flyers were posted online after Texas Woman’s University Institutional Review Board approval. The flyer provided the researcher’s email address and telephone number for interested individuals to respond to the call for study participants. About 250 participants who were interested in the study responded via email and were screened for eligibility using a screening questionnaire. Participants who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded (n = 140). Participants who met the inclusion criteria (N = 110) and signed the electronic consent using DocuSign electronic signature were randomly assigned to the experimental group (n = 55) and control group (n = 55) using GraphPad QuickCalcs.

The principal researcher conducted the random assignment in batches of 20–40 participants to the experimental group (10–20) and the control group (10–20) based on the number of participants recruited within the past four weeks. The software randomly chose a group for each participant. For example, when the researchers assigned 20 participants, the software would show the participant number and the group to which each participant was randomly assigned, with 10 participants in each group. A participant would be randomly assigned to either group A (experimental) or group B (control). The researchers continued the process until all the participants were randomly assigned. Of the 110 eligible participants, 37 declined to participate after signing the consent form because of a lack of sufficient time to attend the two interventions and two data collection sessions. Participants who dropped off after the first intervention reported not having enough time as a reason for withdrawing. A total of 66 participants completed the study: 38 in the experimental group and 28 in the control group. Data from 3 participants were excluded from analysis because of duplication of data (completed the data collection twice). Data analysis was completed for 63 participants. The randomization flow diagram is shown in Figure 1. A $25 electronic gift card was sent to participants who completed the study.

Experimental Group Intervention

The experimental group was assigned to two one-hour virtual education sessions on the importance of HPV vaccination, occurring one week apart, via the Zoom videoconferencing platform and using Microsoft PowerPoint presentation software. A Zoom education session schedule was sent via email to participants, with two Zoom presentation options available twice a week (Tuesdays and Fridays) at 11:30 am and at 5:30 pm for the intervention and data collection sessions. A Saturday option was added at 9:30 am, resulting in a total of five sessions per week, to accommodate participants’ varied work schedules.

The study’s total time commitment was about three hours, including surveys, consent, and instructions. Verbal and written instructions explained the intervention and data collection process. Reminder emails and text messages were sent to participants two days before and two hours before the presentation and data collection.

Zoom security features were enabled to prevent disruptions by unwanted intruders and improve participants’ confidentiality. The meeting link was sent to participants with a password to enter the meeting, and they were placed in the waiting room for the researcher to let them into the class. Participants were advised to turn on their webcams. Before the presentation, clear instructions were provided to participants, and each session of the Zoom class accommodated 5–15 participants.

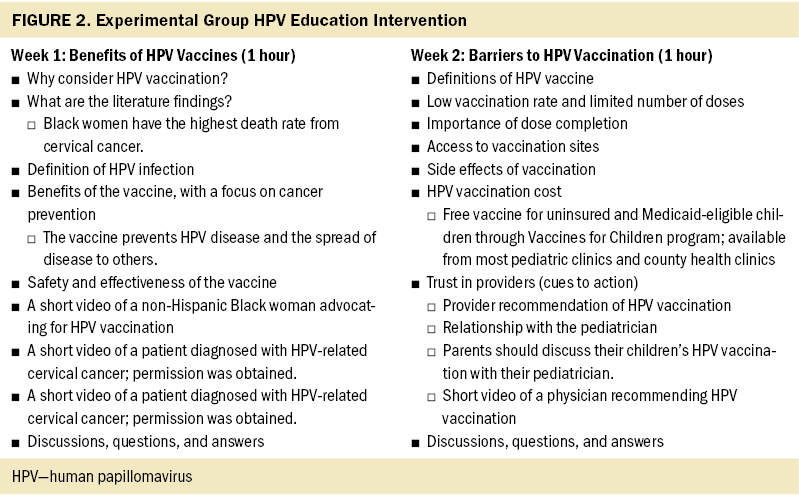

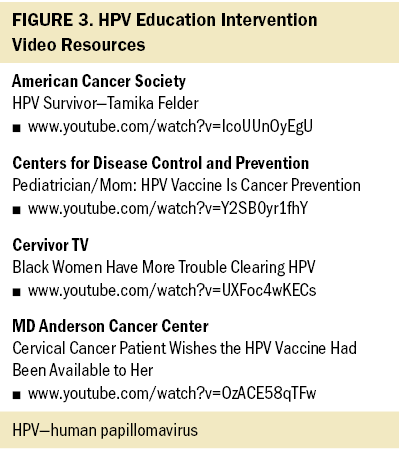

The primary researcher developed the presentation using HPV and HPV vaccination information from the CDC (2019) website. The PowerPoint presentation was presented to participants by the primary researcher. The content for the week 1 presentation included the benefits of HPV vaccination, the definition of HPV infection and how it spreads, information on the types of cancer caused by HPV infection, and the mortality rate of cervical cancer among Black women. The presentation included three short YouTube videos: one video of a Black woman advocating for HPV vaccination (one minute) and two videos of Black women who were cervical cancer survivors stating the importance of HPV vaccination (one minute and three minutes, respectively). The researcher opened and played the videos for participants after the PowerPoint presentation. Participants were encouraged to ask questions, and the researcher engaged them in discussions after the presentations and videos. Some mothers stated they had not vaccinated their children because their pediatrician did not explain the importance of the vaccine in the detail given in the presentation.

The researcher developed and presented the content of the week 2 presentation, which included barriers to HPV vaccination (cost, access, and side effects of the vaccine). One YouTube video used in the week 2 presentation had a Black female pediatrician discussing the importance of HPV vaccination (30 seconds). The researcher opened and played the video for participants after the PowerPoint presentation. Participants were allowed to ask questions and engage in discussion after the presentation and after watching the linked video. The Zoom presentation was interactive, and some mothers stated that they had made an appointment to vaccinate their children after the first week’s presentation. The focus of the entire HPV vaccination education content was on cancer prevention, the benefits of HPV vaccination, barriers to HPV vaccination, and recommendations for the HPV vaccine. An attendance roster was kept, and participants who missed a scheduled intervention or data collection were rescheduled. The experimental group’s intervention is described in Figure 2, and the video resources used in the intervention are provided in Figure 3.

Control Group Intervention

Control group participants were assigned to two virtual one-hour education sessions on healthy nutrition, occurring one week apart, via the Zoom videoconferencing platform and using PowerPoint presentation software. An education session schedule was emailed to participants, with two Zoom presentation options available twice a week (Mondays and Thursdays) at 11:30 am and at 5:30 pm for intervention and data collection. A Saturday option was added at 5:30 pm, resulting in a total of five sessions per week, to accommodate participants’ varied work schedules.

The Zoom meeting link was sent to participants with a password to enter the meeting room. Each session of the Zoom class accommodated 5–15 participants, and reminder emails and text messages were sent to participants two days and two hours before the presentation and data collection.

The educational content for the healthy nutrition sessions included five modules from the Gaples Institute, for which permission had been obtained from Stephen Devries, MD. Three modules that covered the power of healthy nutrition, dietary fat, and carbohydrates were used during week 1. Two modules that covered protein, calcium, sodium, and simple strategies for healthy eating were used during week 2. The primary researcher opened and presented the modules during Zoom sessions for the participants. After viewing the modules, the participants were allowed to ask questions and engage in discussion, and the educational activity was interactive.

At the end of the study, participants interested in HPV vaccination education were instructed to sign up for an optional abbreviated HPV vaccination education session via Zoom. Of the 10 interested participants, only 4 women participated in the abbreviated HPV education session. Most mothers cited limited time as a reason for not participating in the abbreviated HPV education session. The primary researcher developed and presented the abbreviated HPV vaccination presentation content. The video links from YouTube were opened by the researcher via the videoconferencing platform for the participants to watch. The educational activity was interactive, with questions and discussion.

Data Collection

Experimental and control group data were collected immediately after and four weeks after the second intervention using an online survey link through PsychData. The demographic survey data for the experimental and control groups were collected after the first intervention via Zoom. The first data collection was conducted via Zoom immediately after the second intervention, and participants signed up for the second data collection. The participant identification number was sent as a private chat message during Zoom sessions. The second set of data was collected via Zoom four weeks after the second intervention. A data collection survey link and the participant identification number were sent via email to participants who could not attend the second data collection Zoom session. The surveys took about 15 minutes, and the researcher was available during the Zoom sessions to provide instructions and answer questions during data collection. Reminder emails and text messages were sent to participants two days and two hours before the second data collection.

Measures

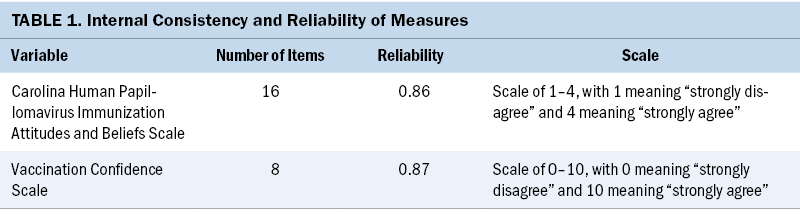

Study outcomes were measured using the VCS and the CHIAS. These two measurement scales captured general vaccination confidence and HPV vaccination attitudes and beliefs among non-Hispanic Black mothers. The study measurement occurred in two layers; the first layer examined overall parental vaccination confidence using VCS factors (benefit, harm, and trust) (Gilkey et al., 2014). The second layer explored HPV-specific parental confidence and attitudes using the CHIAS factors (harm, barrier, effectiveness, and uncertainty) (McRee et al., 2010).

The VCS, developed by Gilkey et al. (2014), has three factors: benefit, which has four response items; harm, which has two items; and trust, which has two items, with a total possible score of eight points. Each item on the eight-item survey about vaccination confidence and belief has a response scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 10 (strongly agree). A response of 7 or greater indicates that a parent is more likely to agree with an item, and a response of 6 or less indicates that the parent is more likely to disagree. Negatively worded items were reverse coded. Previous research has supported the link between the VCS one-factor scale, known as general confidence, and positive parental attitudes to vaccination (alpha = 0.77) (Gilkey et al., 2014). The one-factor scale’s construct validity for a confirmatory factor analysis showed high overall confidence (mean = 8.15, standard error = 0.02). Other studies have supported the validity of the VCS. In a study by Torun and Ertuğrul (2022), the VCS score (total score, benefit score, harm score, and trust score) of parents who stated that the vaccine was necessary significantly higher than the score of parents who thought the vaccine was unnecessary (p < 0.0001, p < 0.001, p = 0.002, and p < 0.001, respectively).

The CHIAS tool, developed by McRee et al. (2010), examines the extent to which attitudes and beliefs are associated with parents’ intention to vaccinate their adolescent child against HPV. It was believed to be the first scale measuring parental attitudes and beliefs regarding HPV vaccination. The 16 items in the HPV vaccine attitudes survey were formed using the four factors of the CHIAS. The measurement tool has a four-point response scale that ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), with a response of “do not know” recorded as the variable’s mean. For each item, higher scores indicate stronger agreement with the statement. Items with barrier questions are rescaled so that the higher values indicate a more significant barrier. Items with negative correlations were reverse coded. In a previous research study, the internal consistency of all four factors was acceptable, with Cronbach’s alphas as follows: perceived vaccination harms, alpha = 0.69; perceived barrier, alpha = 0.69; perceived vaccination effectiveness, alpha = 0.61; and uncertainty about the vaccine, alpha = 0.66. Other research studies show that a decrease in parents’ uncertainties was a significant predictor of vaccine receipt (VanWormer et al., 2017). Each one-point reduction in the uncertainty score is associated with a 4.9-fold increase in likelihood of receiving the next vaccine dose (VanWormer et al., 2017). The CHIAS is a valid instrument for identifying the factors associated with HPV vaccine uptake and parental vaccination intention (Gowda et al., 2012).

The internal consistency and reliability of the study variables were alpha = 0.87 for the VCS and alpha = 0.86 for the CHIAS (see Table 1). These constructs from the VCS and the CHIAS formed the intervention’s education content to increase the non-Hispanic Black mothers’ confidence and attitudes in securing their children’s HPV vaccination.

Data Analysis

Study data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25.0. A descriptive statistic was conducted to communicate the sample’s demographic characteristics. Descriptive statistics for categorical variables were performed using frequencies to identify the number of people who gave each response (e.g., the number of males and females, sex, marital status). The level of the two measurements for the dependent variables VCS and CHIAS was the ordinal scale because the responses were measured on scales of 0–10 and 1–4, respectively. A two-way between-groups ANOVA was used to compare the VCS and CHIAS scores for the control and experimental groups using repeated measures.

Results

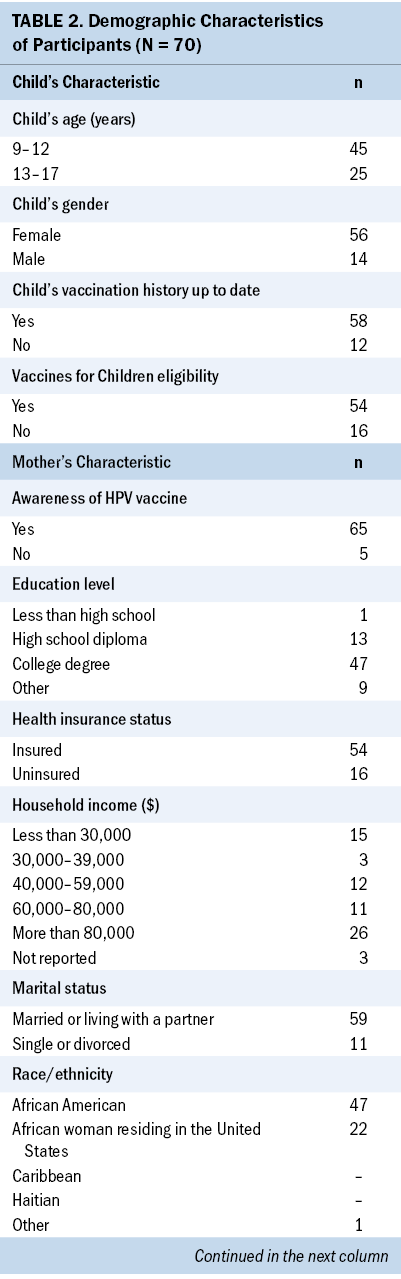

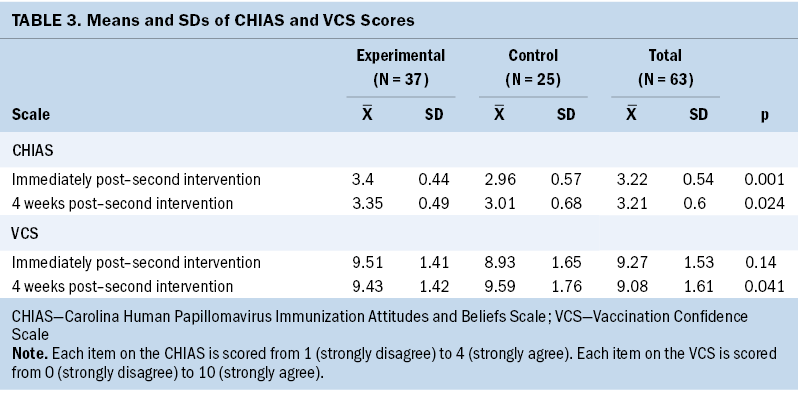

Of the 73 mothers who started the intervention and data collection, 7 withdrew because of a lack of time. A total of 66 mothers completed the study. The attrition analysis was conducted only for loss during the intervention and data collection (n = 7). Demographic data collection was completed for 70 participants. The demographic characteristics showed that of the 70 participants, 45 had children aged 9–12 years and 25 had children aged 13–17 years. Overall, 56 of the children were female and 14 were male. Most participants identified themselves as African American (n = 47) and African women residing in the United States (n = 22). The remaining individual identified herself as “other” but did not specify. No participants in the study self-identified as Caribbean or Haitian. More than half of the mothers resided in Texas (n = 38), followed by Virginia (n = 8), Georgia (n = 7), and New York (n = 7). More than half of the participants had a college degree (n = 47), and 13 had a high school diploma. The annual income of participants was as follows: more than $80,000 (n = 26), $60,000–$80,000 (n = 11), and $40,000–$59,000 (n = 12). Most participants were married or living with a partner (n = 59), 54 were insured, 58 were up to date with their children’s vaccination history, 65 were aware of the HPV vaccine, and 66 were religious or spiritual. The demographic characteristics of participants are described in Table 2.

Repeated Measures ANOVA

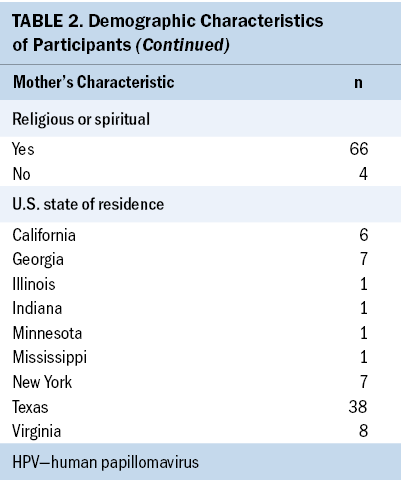

An analysis compared the HPV vaccination confidence, attitude, and belief scores from the experimental and control groups immediately after the intervention and four weeks postintervention. The effect of HPV vaccination education on Black mothers’ confidence, attitudes, and beliefs was examined over time and between groups using the CHIAS and VCS scores. Results indicated that non-Hispanic Black women who received HPV vaccination education reported higher attitudes and beliefs scores in HPV vaccination than the control group. There was a statistically significant interaction between the experimental and control groups (p = 0.002). The post hoc analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in the attitudes and beliefs scores between the experimental and control groups immediately postintervention (p = 0.001) and four weeks postintervention (p = 0.024). Post hoc analysis showed that the experimental group’s attitudes and beliefs score was 0.438 greater than the control group’s score immediately postintervention and 0.345 greater than the control group’s score at four weeks postintervention. Participants’ mean attitudes and beliefs scores immediately postintervention were higher for the experimental group (mean = 3.4, SD = 0.44) than for the control group (mean = 2.96, SD = 0.57). The mean score at four weeks postintervention was higher for the experimental group (mean= 3.35, SD = 0.49) than for the control group (mean= 3.01, SD = 0.68) (see Table 3).

The experimental group reported a higher attitudes and beliefs score regarding HPV vaccination than the control group immediately postintervention and four weeks postintervention. Participants in the experimental group had higher vaccination confidence than participants in the control group. There was a statistically significant difference in vaccination confidence scores between the experimental group and control group (p = 0.049). The post hoc analysis indicated a statistically significant difference in the experimental and control groups at four weeks postintervention (p = 0.041) but not immediately postintervention (p = 0.14). The experimental group reported a higher VCS score than the control group, and the difference was greater at four weeks postintervention than immediately postintervention. The mean VCS score for the experimental group (mean = 9.427) was 0.837 greater than for the control group (mean = 8.59) at four weeks postintervention, indicating that participants in the experimental group had greater HPV vaccination confidence four weeks postintervention.

Discussion

The current study determined the effectiveness of an HPV vaccination education intervention in increasing vaccination confidence, attitudes, and beliefs of non-Hispanic Black mothers with children aged 9–17 years who had not received HPV vaccination. The authors found higher vaccination confidence, more positive attitudes, and greater belief in HPV vaccination among participants who had been randomized to the group that received education about the importance of HPV vaccination. Attitudes and beliefs scores remained high immediately postintervention and at four weeks postintervention, and high vaccination confidence was noted at four weeks postintervention. Results indicate that participants in the experimental group gained HPV vaccination confidence over time after receiving HPV vaccination education. The participants needed time to process the information presented during the intervention before developing a positive belief regarding HPV vaccination.

The findings from the study indicate the effectiveness of the HPV vaccination education intervention. The HPV vaccination education content focused on how well the vaccine works, the safety of the vaccine, and the benefits of the vaccine. The results of the current study are consistent with the results of other studies that indicated a positive relationship between parental attitudes and knowledge of HPV. Cipriano et al. (2018) found that parental attitude modules and an HPV knowledge pretest showed a moderate positive correlation (rs = 0.552, p < 0.001), and the post-test knowledge score was greater than the pretest knowledge score (t = –10.585, p < 0.001). Findings of higher vaccination confidence and more positive attitudes and beliefs regarding HPV vaccination in the current study support findings in a study by Bryer (2014) that examined determinants of Black mothers’ acceptance of HPV vaccination for their daughters. Bryer (2014) found that Black mothers’ attitudes toward HPV vaccination were significantly related to vaccine intention and that vaccine intention correlated with vaccine uptake (r = 0.865, p < 0.001).

Although the current study did not last long enough to measure vaccine uptake, other studies support that participants who received an education intervention are three times more likely to receive a dose of the HPV vaccine (p = 0.003) (Dixon et al., 2019). Mothers with a better understanding of the HPV vaccine are more likely to complete the three doses of the HPV vaccine than those with moderate to low knowledge (Nagpal et al., 2016). An HPV vaccination education intervention that results in higher vaccination confidence and more positive attitudes and beliefs may increase HPV vaccine uptake.

The results of the current study were based on the effectiveness of the education intervention that focused on the benefits of HPV vaccination as cancer prevention, the barriers to HPV vaccination (such as side effects), and the cost of vaccination. The education intervention emphasized the benefits of the HPV vaccine for cancer prevention. Other studies, such as that by Galbraith-Gyan et al. (2019b), showed a positive attitude toward HPV vaccination among Black mothers with regard to the vaccine’s benefit in preventing cancer and infectious diseases.

The intervention and findings of the current study align with the HBM conceptual framework, with its six constructs of perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, perceived benefits, perceived barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy. If mothers believe that their adolescent children are susceptible to HPV infection, with the possible severe consequences of cancer, the mothers will conclude that the benefits of HPV vaccination in preventing cancer outweighs the barriers, such as side effects associated with HPV vaccination. Mothers’ opinions about susceptibility to HPV infection have been found to significantly predict maternal HPV vaccination intention (p = 0.044) (Cunningham-Erves et al., 2018).

The demographic data support other studies that found that education level and household income were associated with adequate knowledge of the HPV vaccine (Strohl et al., 2015). Most participants in the current study had a college degree, an annual income of more than $80,000, and health insurance. The intended participants with lower socioeconomic status were not reached because of the online setting as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although 66 of the 70 participants who provided demographic data reported being spiritual or religious, the experimental group showed higher confidence and more positive attitudes and beliefs regarding HPV vaccination. This was supported by a study conducted by Thompson et al. (2012) to describe the attitudes and social and environmental factors affecting Black parents’ intent to vaccinate their daughters against HPV. In a study by Thompson et al. (2012), participants stated that religious belief would not interfere with HPV vaccination. An extensive literature review on Black mothers’ perception of HPV vaccination of their daughters identified only four randomized controlled trials (DiClemente et al., 2015; Dixon et al., 2019; Joseph et al., 2016; Underwood et al., 2016). The current study has contributed to closing the gap in the limited literature on randomized controlled trials in this population.

The current study was performed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which involved social isolation and lockdowns, resulting in a virtual intervention and data collection. The online intervention offered a better opportunity for more educated participants with higher financial status who could afford computers to participate in the study. The new COVID-19 vaccine discussion was a hot topic in the news, with mixed reactions of some people in favor of the vaccine and others against it. Therefore, it was unclear whether the COVID-19 pandemic, with discussion of the new vaccine, enhanced or decreased non-Hispanic Black mothers’ participation and findings in the current study.

Limitations

The current study was limited to non-Hispanic Black mothers. Additional studies with diverse populations are needed to identify the effect of HPV vaccination education on vaccination confidence and belief for men and women from other racial and ethnic groups. The intervention was focused on the importance of HPV vaccination alone, and the result may not be the same as vaccination in general. The study intervention and data collection were performed through a videoconferencing platform using laptops, computers, and smartphones. Most participants had college degrees and high school degrees, limiting the participation of those with lower socioeconomic and education levels without computers. Additional studies should target non-Hispanic Black mothers from lower socioeconomic groups.

Restrictions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic limited on-site participation in the predominantly non-Hispanic Black churches and organizations with active face-to-face involvement and socialization among this high-risk population. The study was not long enough to measure the effect of HPV vaccination education on the actual rate of HPV vaccination. Additional studies should focus on the vaccination rate among participants who received HPV vaccination education, including the effect of HPV education on non-Hispanic Black mothers with lower socioeconomic status.

Implications for Nursing

Oncology nurses play a significant role in administering cancer treatment, managing the side effects of treatment, and providing patient and caregiver education in the hospital setting. Nurses can participate in more HPV vaccination education studies in the community to enhance parental vaccination confidence, attitudes, and beliefs and improve HPV vaccination intention and uptake among non-Hispanic Black mothers. HPV vaccination education that focuses on the benefits of HPV vaccination as a cancer prevention vaccine was beneficial in improving Black mothers’ attitudes and beliefs regarding HPV vaccination. The findings from the current study indicate that nurses could play a significant role in providing quantitative and randomized controlled trials that focus on HPV vaccine education interventions to enhance vaccination confidence, attitudes, and beliefs among non-Hispanic Black mothers.

The implications for future research will focus on conducting the study on-site, particularly in non-Hispanic Black churches, to see whether the findings differ from those of the current study, which was conducted online via the Zoom videoconferencing platform. An additional research study is needed to explore HPV vaccination uptake among participants in the experimental group. More study participants will be required for future research studies focusing on non-Hispanic Black women with low income and education levels.

Conclusion

The HPV vaccine can effectively prevent precancers and cancers of the oropharynx, anus, penis, cervix, vulva, and vagina. Prevention of HPV infection is of paramount importance among the non-Hispanic Black population because they have the highest cancer mortality rate. A literature review identified limited knowledge, distrust of healthcare providers, benefits of HPV vaccination, and barriers to HPV vaccination as significant factors affecting HPV vaccination uptake among this high-risk population. The current study described the efficacy of an intervention to improve vaccination confidence, attitudes, and beliefs toward HPV vaccination among non-Hispanic Black mothers. Nurses can play a significant role in providing more HPV vaccination education intervention studies to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in cervical cancer. Future studies should focus on the effect of HPV vaccination education interventions on HPV vaccine uptake among this high-risk population.

About the Authors

Stella Ngozi Dike, PhD, RN, OCN®, is a nurse educator at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston; and Sandra K. Cesario, PhD, RNC-OB, FAAN, is a Cornaro Professor and PhD program director, Ann Malecha, PhD, RN, CNE, PHNA-BC, CPH, is a professor, and Rachelle Nurse, PhD, APRN, WHNP-BC, is an associate professor, all in the College of Nursing at Texas Woman’s University in Houston. No financial relationships to disclose. Dike and Malecha completed the data collection. Dike, Cesario, and Malecha provided statistical support. All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design, provided the analysis, and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Dike can be reached at sdike1@twu.edu, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted July 2022. Accepted March 22, 2023.)

References

American Cancer Society. (2019). Cancer facts and figures for African Americans, 2019–2021. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and…

American Cancer Society. (2020). Risk factors for cervical cancer. https://cancer.org/cancer/cervical-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-…

Bryer, J. (2014). Black parents’ beliefs, attitudes, and HPV vaccine intentions. Clinical Nursing Research, 23(4), 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773813487749

Bynum, S.A., Brandt, H.M., Sharpe, P.A., Williams, M.S., & Kerr, J.C. (2011). Working to close the gap: Identifying predictors of HPV vaccine uptake among young African American women. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 22(2), 549–561. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2011.0060

Cassidy, B., Braxter, B., Charron-Prochownik, D., & Schlenk, E.A. (2014). A quality improvement initiative to increase HPV vaccine rates using an educational and reminder strategy with parents of preteen girls. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 28(2), 155–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2013.01.002

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). HPV vaccine schedule and dosing. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://cdc.gov/hpv/hcp/schedules-recommendations.html

Cipriano, J.J., Scoloveno, R., & Kelly, A. (2018). Increasing parental knowledge related to the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 32(1), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2017.06.006

Cunningham-Erves, J., Forbes, L., Ivankova, N., Mayo-Gamble, T., Kelly-Taylor, K., & Deakings, J. (2018). Black mothers’ intention to vaccinate daughters against HPV: A mixed methods approach to identify opportunities for targeted communication. Gynecologic Oncology, 149(3), 506–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.03.047

DiClemente, R.J., Murray, C.C., Graham, T., & Still, J. (2015). Overcoming barriers to HPV vaccination: A randomized clinical trial of a culturally-tailored, media intervention among African American girls. Human Vaccines and Immunotherapeutics, 11(12), 2883–2894. http://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2015.1070996

Dixon, B.E., Zimet, G.D., Xiao, S., Tu, W., Lindsay, B., Church, A., & Downs, S.M. (2019). An educational intervention to improve HPV vaccination: A cluster-randomized trial. Pediatrics, 143(1), e20181457. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-1457

Elam-Evans, L.D., Yankey, D., Singleton, J.A., Sterrett, N., Markowitz, L.E., Williams, C.L., . . . Stokley, S. (2020). National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69(33), 1109–1116.

Fu, L.Y., Zimet, G.D., Latkin, C.A., & Joseph, J.G. (2019). Social networks for human papillomavirus vaccine advice among African American parents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(1), 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.029

Galbraith-Gyan, K.V., Lechuga, J., Jenerette, C.M., Palmer, M.H., Moore, A.D., & Hamilton, J.B. (2019a). African-American parents’ and daughters’ beliefs about HPV infection and the HPV vaccine. Public Health Nursing, 36(2), 134–143.

Galbraith-Gyan, K.V., Lechuga, J., Jenerette, C.M., Palmer, M.H., Moore, A.D., & Hamilton, J.B. (2019b). HPV vaccine acceptance among African-American mothers and their daughters: An inquiry grounded in culture. Ethnicity and Health, 24(3), 323–340.

Gelman, A., Miller, E., Schwarz, E.B., Akers, A.Y., Jeong, K., & Borrero, S. (2013). Racial disparities in human papillomavirus vaccination: Does access matter? Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(6), 756–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.002

Gilkey, M.B., Magnus, B.E., Reiter, P.L., McRee, A.-L., Dempsey, A.F., & Brewer, N.T. (2014). The Vaccination Confidence Scale: A brief measure of parents’ vaccination beliefs. Vaccine, 32(47), 6259–6265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.007

Gottlieb, S.L., Brewer, N.T., Sternberg, M.R., Smith, J.S., Ziarnowski, K., Liddon, N., & Markowitz, L.E. (2009). Human papillomavirus vaccine initiation in an area with elevated rates of cervical cancer. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(5), 430–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.029

Gowda, C., Carlos, R.C., Butchart, A.T., Singer, D.C., Davis, M.M., Clark, S.J., & Dempsey, A.F. (2012). CHIAS: A standardized measure of parental HPV immunization attitudes and beliefs and its associations with vaccine uptake. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 39(6), 475–481. https://doi.org/10.1097/olq.0b013e318248a6d5

Griffioen, A.M., Glynn, S., Mullins, T.K., Zimet, G.D., Rosenthal, S.L., Fortenberry, J.D., & Kahn, J.A. (2012). Perspectives on decision making about human papillomavirus vaccination among 11- to 12-year-old girls and their mothers. Clinical Pediatrics, 51(6), 560–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922812443732

Hall, M.T., Simms, K.T., Lew, J.-B., Smith, M.A., Brotherton, J.M.L., Saville, M., . . . Canfell, K. (2019). The projected timeframe until cervical cancer elimination in Australia: A modelling study. Lancet. Public Health, 4(1), e19–e27. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(18)30183-x

Hamlish, T., Clarke, L., & Alexander, K.A. (2012). Barriers to HPV immunization for African American adolescent females. Vaccine, 30(45), 6472–6476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.07.085

Joseph, N.P., Bernstein, J., Pelton, S., Belizaire, M., Goff, G., Horanieh, N., & Freund, K.M. (2016). Brief client-centered motivational and behavioral intervention to promote HPV vaccination in a hard-to-reach population: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Clinical Pediatrics, 55(9), 851–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922815616244

McRee, A.-L., Brewer, N.T., Reiter, P.L., Gottlieb, S.L., & Smith, J.S. (2010). The Carolina HPV Immunization Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (CHIAS): Scale development and associations with intentions to vaccinate. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 37(4), 234–239. https://doi.org/10.1097/olq.0b013e3181c37e15

Nagpal, J., Linares, L.O., Weiss, J., Schlecht, N.F., Shankar, V., Braun-Courville, D., . . . Diaz, A. (2016). Knowledge about human papillomavirus and time to complete vaccination among vulnerable female youth. Journal of Pediatrics, 171, 122–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.12.070

Nan, X., Madden, K., Richards, A., Holt, C., Wang, M.Q., & Tracy, K. (2016). Message framing, perceived susceptibility, and intentions to vaccinate children against HPV among African American parents. Health Communication, 31(7), 798–805.

Office of Minority Health. (2023). Immunizations and African Americans. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=22

Perkins, R.B., Pierre-Joseph, N., Marquez, C., Iloka, S., & Clark, J.A. (2010). Why do low-income minority parents choose human papillomavirus vaccination for their daughters? Journal of Pediatrics, 157(4), 617–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.04.013

Read, D.S., Joseph, M.A., Polishchuk, V., & Suss, A.L. (2010). Attitudes and perceptions of the HPV vaccine in Caribbean and African-American adolescent girls and their parents. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 23(4), 242–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2010.02.002

Rosenstock, I.M., Strecher, V.J., & Becker, M.H. (1988). Social learning theory and the health belief model. Health Education Quarterly, 15(2), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019818801500203

Strohl, A.E., Mendoza, G., Ghant, M.S., Cameron, K.A., Simon, M.A., Schink, J.C., & Marsh, E.E. (2015). Barriers to prevention: Knowledge of HPV, cervical cancer, and HPV vaccinations among African American women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 212(1), 65.e1–65.e5, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.06.059

Thompson, V.L.S., Arnold, L.D., & Notaro, S.R. (2011). African American parents’ attitudes toward HPV vaccination. Ethnicity and Disease, 21(3), 335–341. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21942167

Thompson, V.L.S., Arnold, L.D., & Notaro, S.R. (2012). African American parents’ HPV vaccination intent and concerns. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 23(1), 290–301. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2012.0007

Torun, E.G., & Ertuğrul, A. (2022). Parental attitudes and knowledge towards childhood vaccination. Journal of Pediatric Infection, 16(1), e35–e40. https://doi.org/10.5578/ced.20229905

Underwood, N.L., Gargano, L.M., Jacobs, S., Seib, K., Morfaw, C., Murray, D., . . . Sales, J.M. (2016). Influence of sources of information and parental attitudes on human papillomavirus vaccine uptake among adolescents. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 29(6), 617–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2016.05.003

VanWormer, J.J., Bendixsen, C.G., Vickers, E.R., Stokley, S., McNeil, M.M., Gee, J., . . . McLean, H.Q. (2017). Association between parent attitudes and receipt of human papillomavirus vaccine in adolescents. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 766. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4787-5

Watkins, K.L., Reitzel, L.R., Wetter, D.W., & McNeill, L.H. (2015). HPV awareness, knowledge and attitudes among older African-American women. American Journal of Health Behavior, 39(2), 205–211. https//doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.39.2.7