Rebuilding and Guiding the Self With Spirituality: A Grounded Theory of Experiences of Adolescents and Young Adults With Cancer

Purpose: To clarify the experiences of spirituality among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer following diagnosis.

Participants & Setting: Participants were recruited at a clinic and on an oncology unit in Turkey. A combination of purposive sampling and theoretical sampling strategy was used to identify 14 participants.

Methodologic Approach: A grounded theory design was used for this study. Semistructured interviews were conducted with each participant between October 2021 and January 2022. The data were analyzed using open, axial, and selective coding.

Findings: All the participants were Muslim, were aged 15–39 years, spoke Turkish, and had undergone treatment for any type of cancer. The core category was identified as rebuilding and guiding the self with spirituality. AYAs connected more closely with their sense of spirituality after being diagnosed with cancer.

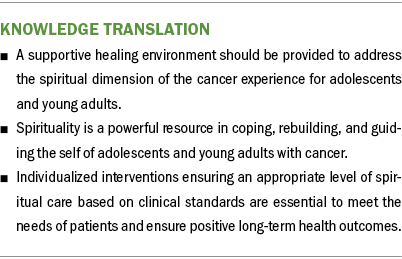

Implications for Nursing: This study demonstrated the importance of providing a supportive healing environment to address the spiritual dimension of the cancer experience for AYAs. Individualized interventions ensuring an appropriate level of spiritual care based on clinical standards are essential to meet the needs of patients and ensure positive long-term health outcomes.

Jump to a section

Cancer and the complex treatments that accompany it have a significant impact on the mental, existential, and spiritual functioning of adolescents and young adults (AYAs), including on their ability to find meaning in life (McNeil, 2016; Robert et al., 2019). Worldwide, more than one million new oncologic diagnoses occur in AYAs annually (Alvarez et al., 2022). Adolescence and young adulthood are typically associated with a long life expectancy (Emerson et al., 2022). Therefore, when AYAs face a potentially terminal disease, such as cancer, they may find it extremely difficult to cope with the fear that it may progress and potentially bring them closer to death (Alvarenga et al., 2021). When individuals are faced with life-threatening diagnoses, religious beliefs and spiritual values may become more meaningful for them. Individuals with cancer may turn to spirituality because of uncertainties concerning their prognosis, decisions about long-term and symptomatic treatment, and evaluations of the treatment process (Kelly et al., 2022). After being diagnosed, AYAs often view spiritual beliefs and values as a source of adaptation, coping, and hope regarding the physical, psychological, and mental effects of the disease (Alvarenga et al., 2021; McNeil, 2016).

Religion and spirituality are similar in theory but different in practice. Religion is an organized, community-based belief system, and spirituality is related to what an individual believes personally. Religion consists of behavior-oriented, outward-directed practices, and spirituality is emotionally oriented and inward directed. Religion includes spirituality, but having spirituality does not necessarily mean having a religion (Litalien et al., 2022; Weathers et al., 2020). Islam is a monotheistic religion that requires submission to God (Lunde, 2002). All Muslims are bound to follow God’s commands and prohibitions. Every Muslim must perform the following religious practices according to the Five Pillars of Islam: faith, prayer, almsgiving, fasting, and pilgrimage. Muhammad is the prophet of the Muslim religion, and his Sunnah and recommendations are considered to be the ultimate guide for Muslims. Prayer calms the hearts of Muslims (Lunde, 2002; Piwko, 2021).

Spirituality is a personal experience that develops over time and is affected by social conditions; it is connected with the search for the meaning of life (Alvarenga et al., 2021; Oh & Kim, 2014). Spiritual well-being encompasses finding satisfaction with life, accepting oneself, having a positive view of the world, and changing perspectives as one gets older (Erdoğan & Koç, 2021). Individuals with cancer can benefit from a range of care modalities, including spiritual care, to improve their health outcomes. Spirituality is considered among the basic psychosocial forms of care for individuals with cancer (Robert et al., 2019). Therefore, adopting an individualized care plan and ensuring an appropriate level of spiritual care based on clinical standards following a cancer diagnosis is one of the principles of contemporary health care (Ghorbani et al., 2021; Szilagyi et al., 2022).

Several theories have highlighted the importance of spirituality for patients. Neuman (2002) presented a systems theory examining a combination of physical, psychological, sociocultural, developmental, and spiritual variables affecting individuals exposed to stress. Neuman believed that an effective holistic approach to care was possible only by understanding the parts. According to this view, the spiritual dimension can be included effectively in nursing care as long as the elements of the intellectual function are positively affected. The spiritual dimension is an essential source of energy and strength in maintaining well-being and achieving stability for the human system (Neuman & Fawcett, 2011). According to Watson’s theory of human caring, the spiritual dimension is an important part of the healing environment (Gürcan & Atay Turan, 2021; Watson, 2009). In this approach, health care supports the spiritual dimension of patients by improving their ability to cope with negative experiences and building their hopes for the future (Watson, 2009).

Previous studies have found that AYAs with cancer can develop strategies to cope with stress by relying on spirituality (McNeil, 2016; Rossato et al., 2021). Although the helpfulness of practices can be subjective, prayer has frequently been cited as a way of getting closer to spirituality and communicating with God (Rossato et al., 2021). A previous study that used grounded theory found that children with cancer and their families kept “the spirit alive” by using strategies like finding meaning in the good things in life (Woodgate & Degner, 2003, p. 103). A study by Hinds and Martin (1988) based on grounded theory described the cognitive process of creating hope in adolescents with cancer. According to this study, the adolescents replaced upsetting thoughts with positive ones to feel better (Hinds & Martin, 1988). Several studies have provided insight into spiritual well-being among AYAs with cancer. These studies have shown that greater spiritual well-being is associated with better adjustment, improved psychological comfort, and a more positive approach to death (Erdoğan & Koç, 2021; McLouth et al., 2021; Park & Cho, 2017). Other studies have shown that improving the resources linked to the quality of spiritual care has positive effects on the physical and mental health outcomes of patients with cancer and can improve their adjustment to the disease and treatment (Ghorbani et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2022; Szilagyi et al., 2022).

Patients with cancer frequently must seek new meaning in life and change their priorities and lifestyles (Neris et al., 2020). Social and spiritual support systems are essential for positive life guidance for AYAs (McNeil, 2016). However, the literature suggests that the emotional and spiritual needs of patients with cancer are not always adequately met (Avutu et al., 2022; Choi et al., 2022; Mesquita et al., 2017). Because most studies on spirituality have been conducted with middle-aged and older adults (Erdoğan & Koç, 2021; McLouth et al., 2021; Niu et al., 2020), very little is known about the topic among AYAs with cancer. There is little information in the literature about how AYAs with cancer are affected by spirituality, how they use spirituality as a coping resource, and what their needs for spiritual support are. A knowledge gap exists concerning the perspectives of AYAs with cancer related to spirituality. The fact that the spiritual dimension is socioculturally important for AYAs with cancer indicates the need for an in-depth investigation of this phenomenon.

Methods

Design

This study aimed to clarify the spiritual experiences of AYAs with cancer. A grounded theory approach (Corbin & Strauss, 2015) was used for this study. This approach was considered most suited to clarifying the relationships among concepts and interpreting the issues that required more comprehensive investigation. The subjective nature of spirituality calls for an in-depth examination. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research were followed to guarantee the explicit and comprehensive presentation of the data (Tong et al., 2007).

Participants and Setting

A combination of purposive sampling and theoretical sampling was used to identify and select diverse participants based on the principles of grounded theory. Purposive sampling was initially preferred to select participants who represented a broad spectrum of views (Palinkas et al., 2015). Theoretical sampling was then used to compare concepts or cases and formulate a conceptual model. With this sampling technique, the research team was ready to change the interview approach, the participants, and the form of data collection as patterns emerged in the data. The theoretical sampling began after the interview with the fourth participant. AYAs were asked to elaborate on emerging concepts during the interviews to provide depth for the theory being developed. Theoretical saturation was reached when repetitive data started to be obtained and no new information about the conceptual categories emerged (Conlon et al., 2020). This study did not require specific characteristics, cancer types, or treatment limits for participants to ensure that a wide range of information was obtained.

The sample consisted of AYAs who had been diagnosed with cancer and were being treated in oncology units in Antalya, Turkey. Adolescents were recruited from an Akdeniz University Hospital–affiliated pediatric hematology-oncology clinic, and young adults were recruited from the oncology unit of the Antalya Education and Research Hospital. Eligible AYAs met the following criteria: (a) being aged 15–39 years, (b) being able to speak Turkish, (c) having undergone cancer treatment, and (d) having been diagnosed with cancer more than three months prior to enrollment. The choice of age range was based on the National Cancer Institute’s definition of AYA (Avutu et al., 2022). The inclusion criterion of three months after diagnosis was selected to ensure that AYAs had gained sufficient awareness and experience regarding the disease and treatment process. The exclusion criterion was being in the terminal stage of the illness. Of those recruited, two adolescents and seven young adults did not wish to participate and share their stories, and three young adults were excluded because they were newly diagnosed. Overall, 4 adolescents and 10 young adults with cancer participated in the current study after meeting the inclusion criteria and providing informed consent. After conducting 14 interviews, the authors judged that data saturation had been achieved (Saunders et al., 2018).

Data Collection

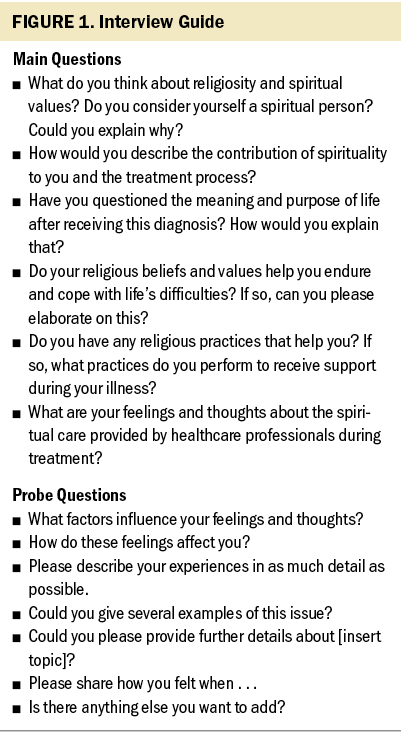

The data were collected between October 2021 and January 2022 during face-to-face interviews that generated detailed contextual information. Data collection was conducted by the first and second authors. Only one interview was held with each patient. A personal information form and a guide comprising six open-ended questions were used during the interviews (see Figure 1). The guide was developed by the authors after several meetings and discussions to focus on key concepts and categories using nondirective qualitative items. It was based on the spirituality and oncology literature as well as on the aims of the current study (Ghorbani et al., 2021; McNeil, 2016). The interviews were conducted at times chosen by the participants in a room in the hospital that was free of stimuli, where a conversation about intimate personal experiences could take place comfortably. The interviews were audio recorded. Each interview lasted an average of 30 minutes.

Ethical Statement

The ethics committee of Akdeniz University, which was associated with the hematology-oncology clinic where the adolescent participants were treated, approved the study. Study permission was also obtained from the Antalya Education and Research Hospital, where the young adult participants were treated. Written and verbal consent were collected from all participants, as well as from the parents of the adolescent participants, prior to the interviews. The aims of the study and the importance of audio recording were explained. The principles of the Declaration of Helsinki were upheld during all stages of the study (Cook et al., 2003). The researcher conducting the interview emphasized that the data would be kept confidential and used only for scientific purposes. Each participant was assigned a unique code number from 1 to 14 to ensure anonymity. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using open, axial, and selective coding. This approach involved a hierarchical, systematic, and constant comparative method, as well as an iterative process. Data generation and analysis were conducted simultaneously (Corbin & Strauss, 2015). The second author transcribed the interviews verbatim, then checked and compared the texts against the audio recordings. The research group met after each interview to analyze the available data and continued to do so as the concepts and categories were developed. These regular meetings were also used to discuss emerging findings, identify where participants’ statements aligned with concepts and categories, and decide on additional interview questions and data collection. Data representing the same basic concepts were assigned labels during coding. In line with the constant comparative approach, a code list was developed. The researchers reviewed and discussed associations and similarities in the codes to achieve a consensus. Using the inductive principle, similar concepts in the data were clustered into categories. Throughout the analysis, the researchers wrote memos to create an audit trail of the decisions made. After analyzing the data, the research team members, who had considerable experience in pediatric oncology and qualitative methods, returned to the literature to better contextualize the findings. Finally, three main categories were uncovered, which were then grouped into a single core category that encompassed them all.

Rigor and Trustworthiness

The study’s trustworthiness was strengthened by relying on the principles of credibility, confirm-ability, dependability, and transferability. For credibility, English–Turkish translation and back-translation methods were used in the transcripts. Direct quotations were taken from the transcripts to maintain the nature of the qualitative content and enhance credibility. In addition, the authors are experts in conducting grounded theory research on this topic. They have extensive clinical and academic experience in their department and have solid knowledge about qualitative and grounded theory research. To improve internal validity, all the members of the research team participated in the analysis by carefully examining and controlling the data. In addition, to increase accuracy and credibility, the researchers engaged at length with the transcripts to code the categories that were most representative of AYAs’ statements. Quotations from different AYAs are reported in the findings section to enhance confirmability. The sampling technique, sample characteristics, and stages of data collection and analysis are described clearly to facilitate transferability (Connelly, 2016; Creswell & Creswell, 2017).

Findings

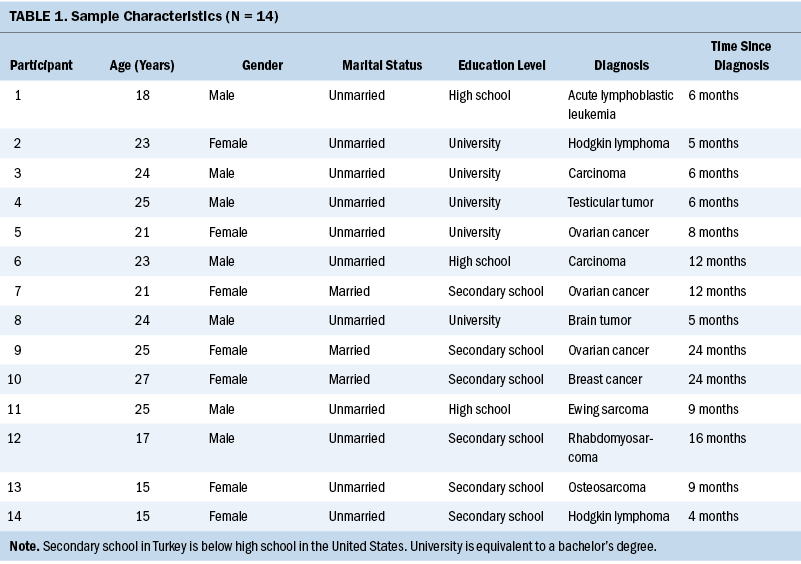

Seven female and seven male individuals aged 15–27 years participated in the study. The average age was 21.6 years (SD = 3.93). The characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

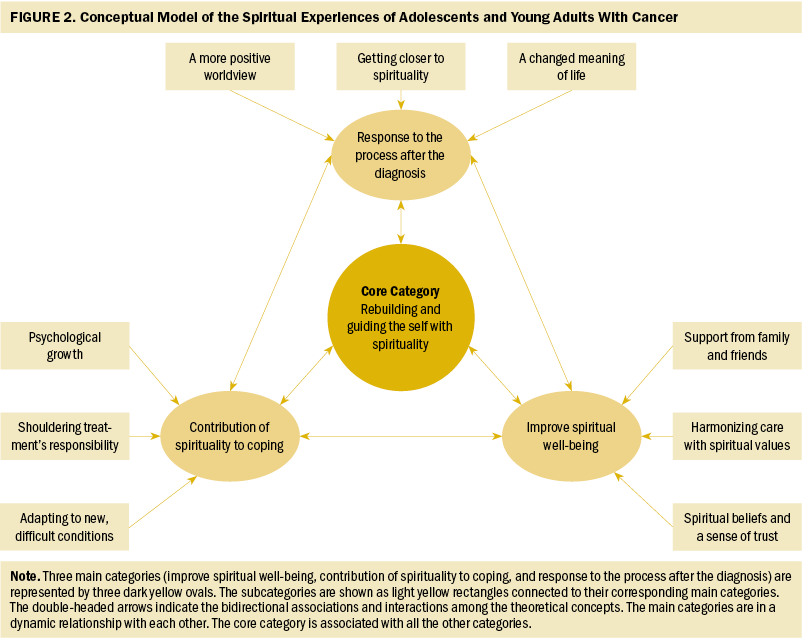

Rebuilding and Guiding the Self With Spirituality

The analysis identified “rebuilding and guiding the self with spirituality” as the core category in the data. The following main categories with related subcategories were also identified: improve spiritual well-being, contribution of spirituality to coping, and response to the process after the diagnosis (see Figure 2).

Improve Spiritual Well-Being

This category consists of the following three subcategories: support from family and friends, harmonizing care with spiritual values, and spiritual beliefs and a sense of trust.

Support from family and friends: All the participants reported that they shared the Islamic religious beliefs of their families. They also felt that the spiritual support of family and friends was very helpful to them. One participant expressed this in the following statement:

My family’s religious beliefs affected me a lot. We have the same religious beliefs. When my mother first learned of my diagnosis, she said, “God gives disease to his loved servants; we will deal with this illness together.” All my family members encouraged and supported me to pray and give thanks to God. (participant 1)

Another participant stated,

My family said that this disease came from God. They also said that I will get better by the grace of God, and we should be patient. My family recommended that I trust in God. My family and friends help to keep my morale high. Their support is the most important thing. They are praying for me. (participant 2)

Harmonizing care with spiritual values: All the participants stated that spiritual care was an essential need for them. They said they needed to talk to healthcare professionals about religion, particularly when they felt unhappy. They also emphasized the importance of thinking about the life of the Prophet. One participant said,

I think that healthcare services should be provided according to the spiritual values of the patients. Talking to friendly and compassionate spiritual counselors and healthcare professionals makes me feel better. Learning the life and the hadiths [guiding suggestions] of our prophet gave me the strength to endure the illness. When I’m struggling in hospital, I ask the healthcare team to pray for me. (participant 3)

Another participant stated,

Healthcare professionals respected me while I was praying. They allowed me to pray and came to the room later. The nurses told me not to lose hope. Furthermore, while the nurses gave me the chemotherapy, they said, “God gives the cure. We hope these medicines will heal you.” (participant 12)

Spiritual beliefs and a sense of trust: Most participants reported that they entrusted themselves to God during the illness. They stated that they felt safe because they believed in God’s mercy and strength. One participant said,

Delivering myself over to God keeps me alive. I believe that everything comes from God. I think this worldly life is temporary. One day we will die due to illness or some other reason. It is completely up to destiny and God’s control. Being sick is not my choice. I believe that God will help me. I trust God, and I feel safe. (participant 4)

Contribution of Spirituality to Coping

This category consists of the following three subcategories: adapting to new, difficult conditions; shouldering treatment’s responsibility; and psychological growth.

Adapting to new, difficult conditions: Most of the participants emphasized that they had found a way to adapt to their new conditions, although they had been upset when first diagnosed and had experienced difficulties during treatment. A participant said,

When the doctor first told me I had cancer, it was as if life had stopped. I asked myself why the cancer had chosen me. But the disease came from God, so I have to accept it. To overcome the disease, it is necessary to accept it. When I was diagnosed with cancer, I was worried that I wouldn’t be able to carry out my dreams. Cancer is a very difficult disease. Rather than asking, “Why me?” I thought, “How can I get better?” (participant 6)

Another participant noted,

There are things that I cannot do due to my physical limitations. My standard of living has worsened. I can’t go out like healthy people, but I try to adapt and find things to do at home. I am on a winding road. Everyone can go fast, but I can’t until I get better. This is my destiny for now. I am behind, but I’ll pick up where I left off. (participant 10)

Shouldering treatment’s responsibility: Although most of the participants suffered during treatment, they were aware of the need to continue the treatment protocols. One participant shared,

When I received chemotherapy, I experienced many difficulties, such as hair loss and fatigue. These side effects made me feel very sad. However, I must make an effort so that God can heal me. It is not right to pray to God for healing without making an effort. Thank God, I know I can be cured. (participant 8)

Another participant said,

Sometimes I do not want to receive treatment continuously because it has many side effects. Too many medications and frequent hospitalizations are exhausting. However, according to my beliefs, it is my responsibility to seek a solution to my health problem. God entrusted this body to me. Therefore, I need to heal. (participant 10)

Psychological growth: Most participants said that after their diagnosis they felt more mature. They said that they no longer got upset about small things, felt more patient, and experienced more control over their behavior. One participant mentioned,

Previously, I used to respond poorly to changes in my body. Now when I’m sad, I pray to God. I feel that I should not get angry and stay calm. My religious beliefs allow me to respond more patiently to negative experiences. I feel distant from bad behavior. After my diagnosis, I felt more mature. (participant 3)

Another participant shared,

I thought I would never get sick or die because I was young. But I realized that sickness and death are part of life. This life is temporary. I will not worry about trivial things anymore. This disease has made me more mature and contributed a lot to my growth. (participant 9)

Response to the Process After the Diagnosis

The third main category consists of the following three subcategories: a more positive worldview, getting closer to spirituality, and a changed meaning of life.

A more positive worldview: Most of the participants stated that after their diagnosis they got closer to religion and spirituality. They believed that having cancer would change their outlook on life in a positive way. They also emphasized that individuals should make the right choices in life. One participant said,

I was afraid of death due to the cancer. Therefore, I turned to spirituality more than before. Better understanding my religion has been very helpful. I have become a more cheerful person. From now on, I will perform my worship completely. I will become a more compassionate and kinder person. I will not treat anyone badly. (participant 4)

Getting closer to spirituality: Most participants said that they had considerable free time during treatment, which allowed them to think more about God. When they prayed, they felt that God heard and saw them. Religious beliefs and spirituality were a source of hope for all the participants, who stated that they got closer to God to improve their health. A participant said,

I believe in God; I have faith. When I am alone at night, I am sometimes in pain. But when I remember God in my heart, I feel his mercy. I think reading the holy book and praying are mysterious forms of worship, because when I do these acts, I feel peace of mind, psychological relief, and motivation. (participant 10)

Another participant stated,

I believe that God loves me. I have a life-threatening illness. Cancer is a test for me. I always pray to God for help. I should not rebel against God; I should be patient, and he will heal me. When I feel hopeless, I think that hope in God is not lost. (participant 5)

A changed meaning of life: Most participants explained that their perspective on life had changed after becoming ill. They stressed that life had become more meaningful. As they faced the reality of illness and death, they realized the importance of taking care of their health. They emphasized the opportunities of life and the many important things in this world. One participant shared,

Previously, I was ambitious. I had many goals and ignored my health to achieve them. But after the diagnosis, my perspective changed. I should not force myself and harm my health to reach those goals. I believe in the afterlife; I believe that this world is a test. We have a responsibility as servants in this world. (participant 6)

Discussion

The current study aimed to clarify the spiritual experiences of AYAs with cancer. The study is the first of its kind to examine this topic in Turkey using grounded theory. Among its novel contributions are the effects of spiritual well-being on coping with cancer and the changes in perspective on life provided by spirituality during treatment.

According to the current study’s findings, the majority of AYAs became closer to spirituality after being diagnosed with cancer. Learning more about their religion seemed to help them considerably. As a result, they decided to engage in more positive behaviors. This finding is supported by other studies of individuals with cancer (Alvarenga et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2022). Most AYAs in the current study said that their outlook on life had changed after the diagnosis. Their expectations changed, and life became more meaningful for them. As they faced the reality of the illness, they developed a more positive perspective on death based on their beliefs. In contrast to the studies that focused on the fear of death in people with cancer (Choi et al., 2022; Upshaw et al., 2021), the current study, which is also supported by the literature (Erdoğan & Koç, 2021), emphasized spiritual hope and resilience. This evidence is important and should be investigated in more detail.

The participants in the current study explained how various religious practices that connected them with the divine affected their motivation and psychological status. Praying was among the most common of these practices. When they prayed, participants believed that God heard and saw them. One of the most striking findings was that most of the participants stated that they felt God’s help immediately after prayer. Previous studies have also shown that religious practices and beliefs are among the most effective ways to cope with a life-threatening illness (McNeil, 2016; Rossato et al., 2021). Participants stated that when they felt the support of a divine being, they became more relaxed. Healthcare teams should be aware of these results to inform their directions and care practices according to individual patient expectations.

Most AYAs in the current study believed that cancer was a test from God. They believed that they would be healed by being patient and trusting in God. An optimistic attitude to the future based on spirituality helped them cope with the difficult experience of cancer treatment. Several previous studies found similar results (Gürcan & Atay Turan, 2020; Nierop-van Baalen et al., 2020; Sabanciogullari & Yilmaz, 2021). The findings from the current study align with the Neuman systems model because the patients developed coping mechanisms for sources of stress to achieve personal system stability and balance (Neuman & Fawcett, 2011). For individuals with cancer, effective coping strategies can positively influence health outcomes.

All the AYAs in the current study needed quality spiritual care. They highlighted the importance of healthcare professionals respecting their religious practices. The participants also wished to talk to friendly, compassionate nurses and spiritual counselors about their beliefs, particularly when they felt sad. This finding supports previous studies that found spiritual care to be a fundamental part of cancer treatment (Abu Khait & Lazenby, 2021; Ghorbani et al., 2021; Szilagyi et al., 2022). Spiritual strategies and meaningful interactions can help to improve patients’ mental health. Contextual conditions, particularly the social environment and the available care resources, can have a positive effect on spiritual well-being. The support of family and friends, as well as the care provided by healthcare professionals who respected their beliefs, was very helpful to the participants. In addition, the results of the current study strengthen Watson’s (2009) argument that providing individualized spiritual care in clinical practice is a potential indicator of quality health services.

All the participants in the current study had beliefs consistent with Islam. However, for AYAs who do not follow a religion, the situation may be different and more complex. Spirituality is a way of being in which a person feels a sense of connectedness to oneself, others, or a higher power (Weathers et al., 2020). AYAs who do not follow a religion may or may not relate to spirituality (Litalien et al., 2022). Therefore, when oncology nurses and other healthcare professionals talk to these AYAs, rather than use concepts like spirituality and religion, they should try exploring their hopes, worries, sense of meaning, and changing life perspectives (Barton et al., 2018).

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Participants were aged 15 years or older and were not newly diagnosed. Younger and newly diagnosed patients may have different experiences of spirituality. Therefore, future studies may wish to examine a more heterogeneous AYA population in terms of age and time since diagnosis.

Implications for Nursing

The findings of this study can be used by oncology nurses, spiritual counselors, and other healthcare professionals to improve the quality of care for individuals with cancer. This study demonstrated the importance of providing oncology nurses with a supportive healing environment to address AYAs’ spiritual needs. Although it may not be possible to be knowledgeable about all religious belief systems, it is essential to approach patients’ views with sensitivity and respect. Nurses should arrange spiritual care practices according to patients’ preferences. To provide holistic care, health professionals should allow patients to perform their spiritual practices in the treatment setting, thereby contributing to the enhancement of their coping skills. In care settings, oncology nurses may create a supportive and guiding environment by facilitating cooperation with spiritual counselors. Understanding the practices required to meet the needs of patients is essential for long-term positive health outcomes. Because spirituality is an important issue for AYAs, it should be included in the in-service training of oncology nurses. AYAs with cancer may have different experiences of spirituality across regions and cultures. Therefore, future research should explore how to provide spiritual support to AYAs who do not follow a religion or who are struggling with spirituality.

Conclusion

This study provides important insights into the spiritual experiences of AYAs with cancer. After being diagnosed, the participants got closer to spirituality. The hope that they derived from this was crucial in facilitating coping. The participants said that they needed quality spiritual care to help improve their mental health and well-being. Therefore, spirituality appears to be a powerful resource for AYAs with cancer in rebuilding and guiding the self. These findings offer a new substantive theory that may be used across social, spiritual, and healthcare contexts. Healthcare professionals can contribute to improving patients’ coping skills by considering the spiritual dimension of care.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the 14 adolescents and young adults who participated in the study.

About the Authors

Orhan Gürsu, PhD, is an associate professor in the Faculty of Theology at Burdur Mehmet Akif Ersoy University in Burdur; and Meltem Gürcan, MSc, RN, is a research assistant and Sevcan Atay Turan, PhD, RN, is an associate professor, both in the Faculty of Nursing at Akdeniz University in Antalya, all in Turkey. No financial relationships to disclose. Gürsu and Gürcan completed the data collection. Gürsu and Atay Turan provided statistical support. All authors contributed to the conceptualization and design, provided the analysis, and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Gürcan can be reached at meltemgurcan@akdeniz.edu.tr, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted July 2022. Accepted February 10, 2023.)

References

Abu Khait, A., & Lazenby, M. (2021). Psychosocial-spiritual interventions among Muslims undergoing treatment for cancer: An integrative review. BMC Palliative Care, 20(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-021-00746-x

Alvarenga, W.A., Leite, A.C.A.B., Menochelli, A.A., Ortiz La Banca, R., De Bortoli, P.S., Neris, R.R., & Nascimento, L.C. (2021). How to talk to children and adolescents with cancer about spirituality? Establishing a conversation model. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 38(2), 116–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454220975703

Alvarez, E.M., Force, L.M., Xu, R., Compton, K., Lu, D., Henrikson, H.J., . . . Bhakta, N. (2022). The global burden of adolescent and young adult cancer in 2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Oncology, 23(1), 27–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00581-7

Avutu, V., Lynch, K.A., Barnett, M.E., Vera, J.A., Glade Bender, J.L., Tap, W.D., & Atkinson, T.M. (2022). Psychosocial needs and preferences for care among adolescent and young adult cancer patients (ages 15–39): A qualitative study. Cancers, 14(3), 710. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14030710

Barton, K.S., Tate, T., Lau, N., Taliesin, K.B., Waldman, E.D., & Rosenberg, A.R. (2018). “I’m not a spiritual person.” How hope might facilitate conversations about spirituality among teens and young adults with cancer. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 55(6), 1599–1608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.02.001

Choi, E., Becker, H., & Kim, S. (2022). Unmet needs in adolescents and young adults with cancer: A mixed-method study using social media. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 64, 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2022.01.019

Conlon, C., Timonen, V., Elliott-O’Dare, C., O’Keeffe, S., & Foley, G. (2020). Confused about theoretical sampling? Engaging theoretical sampling in diverse grounded theory studies. Qualitative Health Research, 30(6), 947–959. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319899139

Connelly, L.M. (2016). Trustworthiness in qualitative research. Medsurg Nursing, 25(6), 435–436.

Cook, R.J., Dickens, B.M., & Fathalla, M.F. (2003). World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. In R.J. Cook, B.M. Dickens, & M.F. Fathalla (Eds.), Reproductive health and human rights: Integrating medicine, ethics, and law (pp. 428–432).Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199241323.003.0025

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed.). Sage.

Creswell, J.W., & Creswell, J.D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage.

Emerson, N.D., Tabuenca, K., & Bursch, B. (2022). End-of-life care in patients with cancer 16–24 years of age. Current Oncology Reports, 24(2), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-021-01173-0

Erdoğan, T.K., & Koç, Z. (2021). Loneliness, death perception, and spiritual well-being in adult oncology patients. Cancer Nursing, 44(6), E503–E512. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0000000000000930

Ghorbani, M., Mohammadi, E., Aghabozorgi, R., & Ramezani, M. (2021). Spiritual care interventions in nursing: An integrative literature review. Supportive Care in Cancer, 29(3), 1165–1181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05747-9

Gürcan, M., & Atay Turan, S. (2020). The experiences of adolescents receiving cancer treatment in Turkey: A qualitative study. European Journal of Cancer Care, 29(5), e13239. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.13239

Gürcan, M., & Atay Turan, S. (2021). Examining the expectations of healing care environment of hospitalized children with cancer based on Watson’s theory of human caring. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(8), 3472–3482. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14934

Hinds, P.S., & Martin, J. (1988). Hopefulness and the self-sustaining process in adolescents with cancer. Nursing Research, 37(6), 336–340. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-198811000-00005

Kelly, E.P., Paredes, A.Z., Tsilimigras, D.I., Hyer, J.M., & Pawlik, T.M. (2022). The role of religion and spirituality in cancer care: An umbrella review of the literature. Surgical Oncology, 42, 101389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.suronc.2020.05.004

Litalien, M., Atari, D.O., & Obasi, I. (2022). The influence of religiosity and spirituality on health in Canada: A systematic literature review. Journal of Religion and Health, 61(1), 373–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01148-8

Lunde, P. (2002). Islam: Faith, culture, history. Dorling Kindersley.

McLouth, L.E., Ford, C.G., Pustejovsky, J.E., Park, C.L., Sherman, A.C., Trevino, K., & Salsman, J.M. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of effects of psychosocial interventions on spiritual well-being in adults with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 30(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5562

McNeil, S.B. (2016). Spirituality in adolescents and young adults with cancer: A review of literature. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 33(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043454214564397

Mesquita, A.C., de Cássia Lopes Chaves, É., & de Barros, G.A.M. (2017). Spiritual needs of patients with cancer in palliative care: An integrative review. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care, 11(4), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000308

Neris, R.R., Nascimento, L.C., Leite, A.C.A.B., de Andrade Alvarenga, W., Polita, N.B., & Zago, M.M.F. (2020). The experience of health-related quality of life in extended and permanent cancer survivors: A qualitative systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 29(10), 1474–1485. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5472

Neuman, B. (2002). Appendix C: Assessment and intervention based on the Neuman systems model. In B. Neuman & J. Fawcett (Eds.), The Neuman systems model (4th ed., pp. 347–359). Prentice Hall.

Neuman, B., & Fawcett, J. (2011). The Neuman systems model (5th ed.). Pearson.

Nierop-van Baalen, C., Grypdonck, M., van Hecke, A., & Verhaeghe, S. (2020). Associated factors of hope in cancer patients during treatment: A systematic literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(7), 1520–1537. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14344

Niu, Y., McSherry, W., & Partridge, M. (2020). An understanding of spirituality and spiritual care among people from Chinese backgrounds: A grounded theory study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(10), 2648–2659. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14474

Oh, P.-J., & Kim, S.H. (2014). The effects of spiritual interventions in patients with cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(5), E290–E301. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.e290-e301

Palinkas, L.A., Horwitz, S.M., Green, C.A., Wisdom, J.P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 42(5), 533–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Park, C.L., & Cho, D. (2017). Spiritual well-being and spiritual distress predict adjustment in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 26(9), 1293–1300.

Piwko, A.M. (2021). Islam and the COVID-19 pandemic: Between religious practice and health protection. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(5), 3291–3308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01346-y

Robert, R., Stavinoha, P., Jones, B.L., Robinson, J., Larson, K., Hicklen, R., . . . Weaver, M.S. (2019). Spiritual assessment and spiritual care offerings as a standard of care in pediatric oncology: A recommendation informed by a systematic review of the literature. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 66(9), e27764. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.27764

Rossato, L., Ullán, A.M., & Scorsolini-Comin, F. (2021). Religious and spiritual practices used by children and adolescents to cope with cancer. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(6), 4167–4183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01256-z

Sabanciogullari, S., & Yilmaz, F.T. (2021). The effect of religious coping on hope level of cancer patients receiving chemotherapy. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(4), 2756–2769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00944-1

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., . . . Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality and Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

Szilagyi, C., Lion, A.H., Varner Perez, S.E., Koch, S., Oyedele, O., Slaven, J.E., . . . Puchalski, C.M. (2022). Interprofessional spiritual care education in pediatric hematology-oncology: A pilot study. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 69(3), e29515. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.29515

Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

Upshaw, N.C., Roche, A., Gleditsch, K., Connelly, E., Wasilewski-Masker, K., & Brock, K.E. (2021). Palliative care considerations and practices for adolescents and young adults with cancer. Pediatric Blood and Cancer, 68(1), e28781. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.28781

Watson, J. (2009). Caring science and human caring theory: Transforming personal and professional practices of nursing and health care. Journal of Health and Human Services Administration, 31(4), 466–482. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25790743

Weathers, E., Coffey, A., McSherry, W., & McCarthy, G. (2020). Development and validation of the Spirituality Instrument-27© (SpI-27©) in individuals with chronic illness. Applied Nursing Research, 56, 151331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2020.151331

Woodgate, R.L., & Degner, L.F. (2003). A substantive theory of keeping the spirit alive: The spirit within children with cancer and their families. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 20(3), 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1053/jpon.2003.75