Factors Influencing Nurses’ Use of Hazardous Drug Safe-Handling Precautions

Purpose/Objectives: To identify factors associated with oncology nurses’ use of hazardous drug (HD) safe-handling precautions in inpatient clinical research units.

Design: Descriptive, cross-sectional.

Setting: The National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland.

Sample: 115 RNs working on high-volume HD administration units.

Methods: Survey data were collected online using the Hazardous Drug Handling Questionnaire. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and multiple regression analysis.

Main Research Variables: Exposure knowledge, self-efficacy, barriers to personal protective equipment use, perceived risk, conflict of interest, interpersonal influences, workplace safety climate, and total mean HD precaution use.

Findings: Participants demonstrated high exposure knowledge, self-efficacy, perceived risk, interpersonal influences, and workplace safety climate. Participants demonstrated moderate barriers and conflict of interest. Total mean HD precaution use proved highest during HD administration and lowest for handling excreta at 48 hours. Average patients per day significantly influenced total HD precaution: nurses exhibited more HD precaution use when assigned fewer patients.

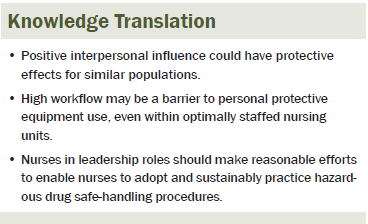

Conclusions: Despite high exposure knowledge, barriers to personal protective equipment use and conflict of interest may contribute to reduced adoption of personal protective practices among oncology nurses.

Implications for Nursing: Hospital and unit-specific factors captured by the predictor variables could contribute to institutional HD policy.

Jump to a section

Hazardous drugs (HDs) are defined by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health ([NIOSH], 2004) using one or more of the following criteria: carcinogenicity, teratogenicity, reproductive toxicity, genotoxicity, organ toxicity at low doses, and drugs that mimic existing HDs in structure or toxicity. Most of the drugs that match the HD description are cytotoxic antineoplastic agents; however, other classes of drugs are included in this category, such as antivirals, antibiotics, and hormones (NIOSH, 2004).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ([CDC], 2012), about 8 million healthcare providers in the United States work in environments that could increase their risk of HD exposure. Exposure occurs via inhalation, dermal absorption, ingestion, or contact with conjunctiva (NIOSH, 2004). HD exposure risk occurs during drug-handling activities, such as administration, preparation, and disposal of the drug and patient excreta (Polovich & Martin, 2011). Nurses working in oncology settings frequently handle chemotherapeutic agents, making the nurses particularly vulnerable to exposure.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (1999) published guidelines in 1986 for the safe-handling of cytotoxic drugs in the workplace (Yodaiken & Bennett, 1986). This publication was the first to recognize the critical need for workplace HD safe handling practices. Subsequently, standards for the safe handling of antineoplastic drugs also were published by professional associations, including the International Society of Oncology Pharmacy Practitioners (2007) and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (2006). All guidelines and standards emphasized the importance of using closed-system transfer devices and personal protective equipment (PPE) to reduce risk.

Prior to the development of protective standards, however, healthcare provider HD exposure resulted in toxicities and reproductive effects, such as fetal defects and difficulties with fertility (Connor, Lawson, Polovich, & McDiarmid, 2014; Eisenberg, 2009; Polovich, 2011). Those who had direct contact with patients receiving HDs reported acute symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, headaches, dizziness, rash, shortness of breath, and hair loss—symptoms similar to patients receiving these drugs (Valanis, Vollmer, Labuhn, & Glass, 1993). Genotoxic effects also have been reported (Jakab, Jeno, & Tompa, 2001). Fuchs et al. (1995) demonstrated genotoxicity by collecting blood samples from nurses administering HD and found that DNA single-strand breaks and alkali labile sites in peripheral blood lymphocytes were 50% higher when compared to controls.

Despite the establishment of protective standards, growing evidence demonstrates the toxicity and detrimental effects that HD exposure can have on fertility and reproductive health, such as spontaneous abortion, miscarriages, infertility, and birth defects (Fransman et al., 2007; Lawson et al., 2012; Valanis, Vollmer, & Steele, 1999). Given that the majority of the nursing workforce is female (90%) and within childbearing years (median age of 31), the relevance of these effects is notable (Spratley, Johnson, Sochalski, Fritz, & Spencer, 2001; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2010). The risk of exposure persists because of environmental contamination and poor healthcare worker adherence to current HD safe-handling recommendations and guidelines (Nixon & Schulmeister, 2009; Polovich & Martin, 2011; Sessink, Connor, Jorgenson, & Tyler, 2010).

Suboptimal recommendation and practice adoption have been illustrated in several studies (Martin & Larson, 2003; Polovich & Clark, 2012; Polovich & Martin, 2011). For example, the results from a study of nurses working in oncology centers in the United States indicated that although exposure knowledge, self-efficacy for using PPE, and perceived risk of harm from HD exposure were high, total precaution use was low (Polovich & Clark, 2012). Within this sample, the majority of nurses practiced in outpatient settings in a physician office or community hospital and reported administering chemotherapy to an average of 6.8 patients per day. HD safe-handling policies were present, but many did not reflect current recommendations.

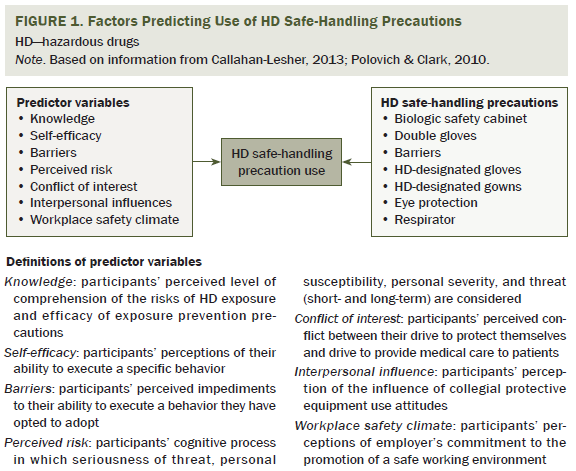

The Factors Predicting Use of Hazardous Drug Safe-Handling Precautions model was used to guide Polovich and Clark’s (2012) study. The model suggests that knowledge of the hazard is related to perceived risk and self-efficacy. Higher self-efficacy for using PPE and positive workplace safety climate are expected to decrease perceived barriers. Perceived risk, exposure knowledge, self-efficacy, barriers, workplace safety climate, interpersonal influences, and conflict of interest serve as the predictor variables (see Figure 1) and are expected to affect use of safe-handling precautions.

The purpose of the current study was to examine the HD safe-handling practices of oncology nurses working on inpatient units at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center (NIH CC) in Bethesda, Maryland, using the Factors Predicting Use of Hazardous Drug Safe-Handling Precautions model. The NIH CC is solely dedicated to clinical research and has robust HD policies and procedures that encompass the required Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) HD safe-handling training program.

Methods

Sample

This study used a cross-sectional, correlational design. Participants were recruited via email invitation, using unit-based Listservs, from 196 eligible RNs working at the NIH CC. The NIH CC contains 240 inpatient beds with 108 of these beds on five clinical units identified by NIH CC pharmacy standards as high-volume users of HDs. The final sample was drawn from these units and consisted of nurses on four oncology units and one intensive care unit. Nurses working on these units are required to complete the institutional annual review course on safe handling of HD and to successfully complete the ONS chemotherapy/biotherapy certificate course. Employment at the NIH CC in one of the aforementioned units and handling of HDs were the only eligibility requirements for study participation.

Instrument

The Hazardous Drug Handling Questionnaire (HDHQ) developed by Polovich and Clark (2012) was used to measure nurses’ use of HD safe-handling precautions. The tool consists of 65 questions that measure seven predictor variables: exposure knowledge, self-efficacy, perceived risk, barriers, interpersonal influences, conflict of interest, and workplace safety climate. The tool is statistically reliable with Cronbach alphas for the predictor variables ranging from 0.7–0.93 (Polovich & Clark, 2012).

The HDHQ development and psychometrics are described in detail elsewhere (Polovich & Clark, 2012). The current authors are unaware of other reliable tools to assess occupational exposure or nurse’s safety-related perceptions regarding HD safe-handling precautions.

Procedures

Following receipt of the NIH Office for Human Subjects Research Protection approval, the confidential, anonymous, voluntary electronic survey was loaded onto SurveyMonkey®, a web-based survey platform. The survey was made available through a secure website; no log-on or password was required. Each participant was assigned a unique study number known only to the study team and appeared together on one document accessible only to the study team. The initial survey invitation and announcement was emailed to the survey population via a secure server about three days before the online survey was initiated, and participants were informed that they had six weeks to complete the survey. A follow-up email was sent one week after the survey was launched to remind nurses that the survey was still available (Dillman, Smyth, & Christian, 2009). To increase response rate, additional emails were sent at two and three weeks after survey initiation. Participation implied consent. Participants were offered no compensation for completing the survey. The survey took about 30 minutes to complete, and the link remained active for six weeks.

Data Analysis

The SurveyMonkey software database was downloaded into Microsoft® Excel®. All data analyses were done using SPSS®, version 21.0. Frequencies, percentages or means, and standard deviations were used to describe categorical or continuous characteristics of the sample and the main study variables. Spearman’s correlation coefficients were calculated to measure the relationship between demographic and predictor variables and safe-handling precautions. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to test the safe-handling precaution differences between demographic groups. Hierarchical multiple linear regression was performed with significant demographic and predictor variables. The first block included all significant demographic variables. Significant predictor variables were then added to the model in the second block. R2 change was used to evaluate the predictor variables’ effect. Multicollinearity was checked using tolerance and variance inflation factor scores. For all analyses, p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

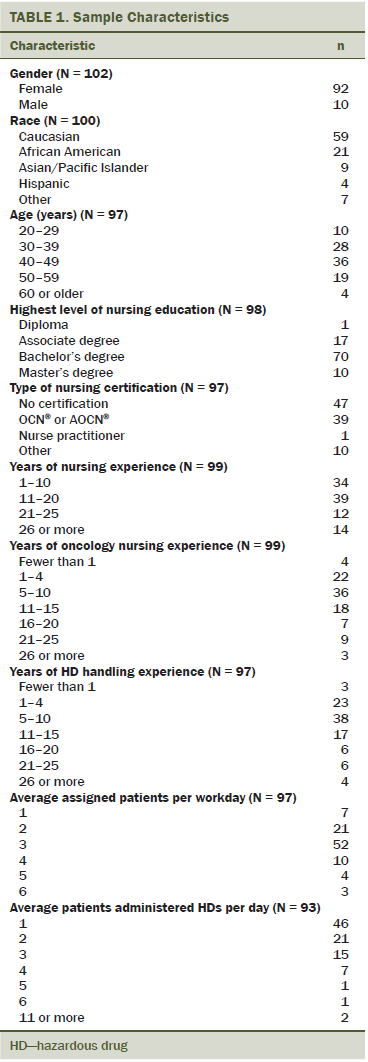

Of the 196 eligible clinical research nurses, 115 participated in the survey for a response rate of 59%. The majority of respondents were female (90%), Caucasian (59%), aged 30–49 years (66%), had a baccalaureate degree in nursing (71%), and worked full-time (76%) (defined as 40 hours per week). Most nurses were very experienced in nursing (66% had more than 10 years in nursing), oncology nursing (74% had more than 5 years), and chemotherapy handling (73% had more than 5 years). Most reported completing the ONS chemotherapy and biotherapy training course (96%), whereas half reported being an ONS member. Less than half were certified in oncology nursing (40%). The majority of nurses (54%) were assigned an average of three patients per day. Half reported personally administering chemotherapy to one patient per day, followed by 23% and 17% who reported personally administering chemotherapy to two and three patients, respectively. Ten participants (9%) reported experiencing a HD exposure event during the previous 12 months. The sample demographics are summarized in Table 1.

Predictor Variables

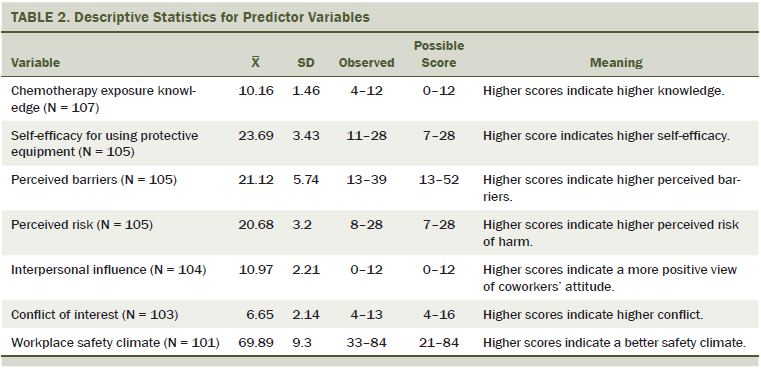

Nurses had high chemotherapy exposure knowledge, with respondents achieving a mean score of 10.16 (SD = 1.46) on a score range of 1–12. The item most often answered incorrectly (54 of 102 nurses, 53%) was, “Surgical mask provides protection from hazardous drug aerosols.” The correct answer is false. In addition, 41 of 107 nurses (38%) incorrectly identified the following statement as true: “Hazardous drugs cannot enter the body through contact with contaminated surfaces,” and 33 of 106 nurses (31%) incorrectly identified the following statement as false: “Hazardous drug gas and vapor in the air can enter the body through skin and mucous membranes.”

Nurses reported high self-efficacy and moderate barriers to using PPE for HD handling. Perceived barriers included PPE being uncomfortable to wear, such as PPE making nurses feel too hot. Nurses perceived moderate conflict of interest when handling chemotherapy. Nurses reported high interpersonal influence, which resulted in a positive influence on their own use of HD precautions.

Nurses noted high perceived risk of harm from HD exposure. A high workplace safety climate was reported with the exception of workplace safety during times of high workflow; in response to the statement, “I usually do not have too much to do so that I can follow HD safe-handling precautions,” 44% of respondents disagreed. Table 2 shows the statistics for the predictor variables.

Nurses’ Use of Safe-Handling Precautions

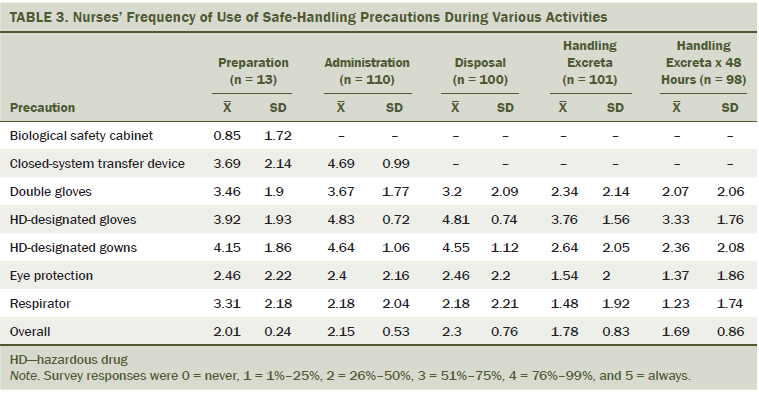

As shown in Table 3, only 13 nurses (11%) reported participating in HD preparation activities. Most nurses reported that they administered HD, disposed of HD, handled HD-contaminated excreta, and handled excreta within 48 hours after HDs were received. Use of HD-designated gloves was high for all HD handling activities. When handling excreta, HD-designated gloves were used consistently, with a slight decrease noted for excreta disposed 48 hours after HD administration. Gown use was high for all handling activities except when handling excreta. Use of double gloves, eye protection, and respiratory protection was moderate for preparation, administration, and disposal activities and low when handling excreta. Use of a closed-system transfer device was moderate for preparation activities and high for HD administration. Overall, precaution use was highest for HD disposal and lowest for handling excreta at 48 hours.

Relationships Between Variables

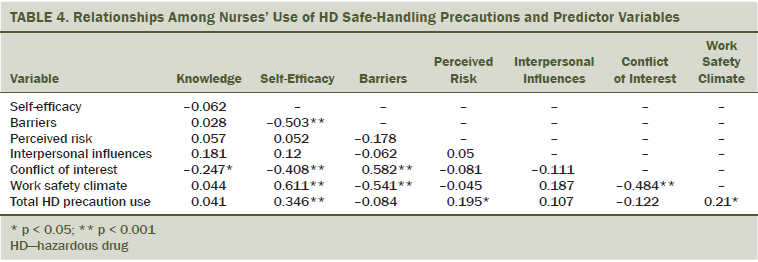

Table 4 displays the relationships between nurses’ use of HD safe-handling precautions and the predictor variables. Total HD precaution use was associated with self-efficacy, perceived risk, and workplace safety climate. Higher knowledge was associated with a lower conflict of interest. Higher self-efficacy was associated with fewer barriers, lower conflict of interest, a better workplace safety climate, and total HD precaution use. Perceived barriers were associated with higher conflict of interest and a poorer workplace safety climate. Higher conflict of interest was associated with a poorer workplace safety climate.

Only 10 participants reported experiencing an HD exposure during the course of the year prior to the survey. Not enough variance existed to determine a difference between those who had experienced an exposure and those who had not experienced an exposure and the use of safe-handling precautions.

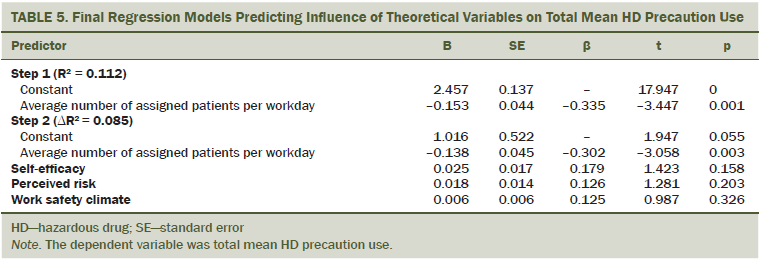

Multiple regression analyses results appear in Table 5. Although significant relationships were found in the correlation analyses between self-efficacy, perceived risk, workplace safety, and total HD precaution use, after controlling for all the other covariates in the model, none of those three remained significant in the final regression model. A significant relationship between total HD precaution use and mean number of patients assigned per day was found such that, after controlling for self-efficacy, perceived risk, and workplace safety, nurses in this sample exhibit more HD precaution use when assigned fewer patients.

Discussion

The current study found that inpatient oncology nurses working at the NIH CC were knowledgeable in HD handling, had high self-efficacy, perceived barriers to using PPE to be low and HD-related risk to be high, identified that their coworkers value safe handling, had a moderate level of conflict of interest between caring for the patient and adhering to safe-handling recommendations, and reported the workplace safety climate to be high. The nurses in this study all worked on inpatient units and reported administering HDs to 1–2 patients per day.

Only 10 participants (less than 10%) reported an HD exposure. NIOSH (2004) reports that, annually, 8 million healthcare workers are at risk for an HD exposure based on their place of work. On average, the nurses in this setting administer 1,100 HD preparations per month. This is equivalent to 13,200 preparations per year; a majority of these preparations are administered on the units involved in the study sample. In addition, of note is the high HD exposure reporting rate captured in this study; of the 10 nurses who experienced an exposure, 9 stated that they reported the exposure. The low levels of HD exposure reported in this study could be attributed to several factors: participant nurses are experiencing low frequency of HD exposures, they are not reporting HD exposures, they did not answer the survey item truthfully, or a combination of these factors. Perhaps adherence to updated hospital policies and procedures significantly reduced the number of exposures. Elucidation of the specific factors and conditions that contribute to low frequency of reported HD exposure will have important implications for safe nursing practice and patient care. Therefore, additional analyses are required to examine environment- and population-specific factors that lead to oncology nurses reporting a low rate of HD exposure.

This study demonstrates that HD safe-handling precaution use in this environment is higher, in all activities assessed, than previous studies; however, room for improvement still exists. Results from this study support a concern that rates of HD safe-handling precaution use prove lower than would be predicted based on high levels of reported knowledge, high self-efficacy, chemotherapy-handling experience, high perception of risk, high interpersonal influence, a workplace safety climate that is perceived to be high in addition to low barriers to adherence, and conflict of interest (Martin & Larson, 2003; Polovich & Clark, 2012; Polovich & Martin, 2011). Among this study population, use of personal precautions was moderate, just over 50% during most activities, with HD disposal being the highest (mean = 2.3) and within 48 hours of HD administration excreta management being the lowest (mean = 1.69).

Additional research is needed to investigate why, despite optimal nurse–patient ratios, participants reported that they spent the majority of their time (80%) caring for 1–3 patients per day (an optimal nurse–patient ratio for the provision of safe, efficient, and effective care for patients on complex research protocols). Participants reported decreased perception of workplace safety during times of high workflow. The current study confirmed the influence of high workload, measured by nurse–patient ratio, as a significant barrier to nurse HD precaution adoption; mean number of patients assigned per day proved the only significant predictor of HD precaution use, with more patients assigned per day predicting less nurse HD precaution use controlling for self-efficacy, perceived risk, and workplace safety (Geer, Curbow, Anna, Lees, & Buckley, 2006; Mahon et al., 1994; Valanis, McNeil, & Driscoll, 1991). In contrast, Polovich and Clark (2012) found that two additional theoretical predictor variables, perceived barriers and workplace safety climate, significantly influenced HD precaution use.

Limitations

The self-report survey was conducted in one specialized research hospital and cannot be generalized without replication to other settings. Nurses at the NIH CC are required to complete formal training to administer chemotherapy and biotherapy and are encouraged to gain oncology nursing certification. These institutional requirements are likely to distinguish the behavior and experience of participants in this study from nurses who have not received similar training.

Despite the limitations, this study provides information about the HD exposure and handling practices and perceptions of oncology nurses within a national health organization. In addition, the authors examined relationships between key predictor variables and oncology nurse HD safe-handling precaution use. Research nurses work with compounds with unknown hazardous profiles; therefore, this study can help to improve and reform the practice of handling HDs within the NIH CC. An additional strength of this study is that, if the self-reported exposure is valid, other institutions could potentially adopt the study organization’s comprehensive safe-handling program.

Implications for Education and Practice

The NIH CC admits only patients with a precise diagnosis or stage of illness under investigation, and all patients consent to participate in research studies (protocols). Nursing at NIH CC is unique in that all nurses are integral research team members engaged in providing care to patients on active research protocols. Clinical research nurses working on oncology and non-oncology inpatient units administer cytotoxic and biologic agents with known occupational exposure risks, as well as many other compounds (e.g., investigational drugs) where the occupational hazardous profiles are not yet established. Therefore, nurses must correctly and consistently use HD safe-handling precautions to prevent opportunities for occupational and environmental exposure.

According to Sammer, Lykens, Singh, Mains, and Lachan (2010), engaged leaders drive the organizational safety climate by designing strategy and building structures that guide safety processes and outcomes. The NIH CC leadership is highly committed to and engaged in advancing employee HD safe-handling strategies. Recent efforts demonstrate this commitment. Safe-handling efforts have included a review of standards of practice and procedures, specifically focusing on current and evidence-based practices, updated PPE (including a trial and implementation of solid-front hazardous drug gowns), and the implementation of a closed-system drug transfer device, which decreases exposure by creating a closed system during preparation, administration, and disposal (during disconnect). This study evidences the outcomes of those efforts related to nurses’ perceptions and practices regarding HD safe-handling precautions and identifies specific areas of improvement related to precaution adoption. The findings demonstrate that the NIH CC has created a working environment in which safe handling of HDs is a priority for all employees.

Conclusion

An HD safe-handling program is necessary to offer the highest level of protection to prevent unavoidable exposure risks. A comprehensive program includes formal education and training programs and the deployment of safety and engineering controls, such as closed-system drug transfer devices, biological safety cabinets, and the consistent use of PPE. PPE includes gowns, double gloving, goggles, and masks, including masks with a face shield when appropriate and respiratory masks when aerolsolization is possible to protect the provider from immediate exposures (American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, 2006; NIOSH, 2008; Polovich, 2011).

References

American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. (2006). ASHP guidelines on handling hazardous drugs. American Journal of Health System Pharmacy, 63, 1172–1193. doi:10.2146/ajhp050529

Callahan-Lesher, A. (2013). The factors influencing the use of hazardous drug safe-handling precautions among nurses working in an acute care oncology research setting [Unpublished dissertation]. Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Workplace safety and health topics: Hazardous drug exposures in health care. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hazdrug

Connor, T.H., Lawson, C.C., Polovich, M., & McDiarmid, M.A. (2014). Reproductive health risks associated with occupational exposures to antineoplastic drugs in health care settings: A review of the evidence. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56, 901–910. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000249

Dillman, D.A., Smyth, J.D., & Christian, L.M. (2009). Internet, phone, mail, and mixed-mode surveys: The tailored design method (3rd ed.). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Eisenberg, S. (2009). Safe-handling and administration of antineoplastic chemotherapy. Journal of Infusion Nursing, 32, 23–32.

Fransman, W., Roeleveld, N., Peelan, S., de Kort, W., Kromhout, H., & Heederik, D. (2007). Nurses with dermal exposure to antineoplastic drugs: Epidemiology, 18, 112–119.

Fuchs, J., Hengstler, J.G., Jung, D., Hiltl, G., Konietzko, J., & Osech, F. (1995). DNA damage in nurses handling antineoplastic agents. Mutation Research, 342, 17–23. doi:10.1016/0165-1218(95)90086-1

Geer, L.A., Curbow, B.A., Anna, D.H., Lees, P.S., & Buckley, T.J. (2006). Development of a questionnaire to assess worker knowledge, attitudes and perceptions underlying dermal exposure. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health, 32, 209–218.

International Society of Oncology Pharmacy Practitioners. (2007). ISOPP standards of practice: Safe-handling of cytotoxics. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice, 13, 1–81.

Jakab, M.G., Jeno, M., & Tompa, A. (2001). Follow-up genotoxicological monitoring of nurses handling antineoplastic drugs. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, 62, 307–318.

Lawson, C.C., Rocheleau, C.M., Whelan, E.A., Hibert, E.N.L., Grajewski, B., Spiegelman, D., & Rich-Edwards, J.W. (2012). Occupational exposures among nurses and risk of spontaneous abortion. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 206, e1–e8.

Mahon, S.M., Casperson, D.S., Yackzan, S., Goodner, S., Hasse, B., Hawkins, J., . . . Witcher, V. (1994). Safe handling practices of cytotoxic drugs: The results of a chapter survey. Oncology Nursing Forum, 21, 1157–1165.

Martin, S., & Larson, E. (2003). Chemotherapy-handling practices of outpatient and office based oncology nurses. Oncology Nursing Forum, 30, 575–581. doi:10.1188/03.ONF.575-581

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2004). NIOSH alert: Preventing occupational exposures to antineoplastics and other hazardous drugs in the healthcare settings. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2004-165/pdfs/2004-165.pdf

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2008). NIOSH Workplace Solution: Personal protective equipment for health care workers who work with hazardous drugs. Cincinnati, OH: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nixon, S., & Schulmeister, L. (2009). Safe-handling of hazardous drugs: Are you protected? Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 13, 433–439. doi:10.1188/09.CJON.433-439

Occupational Safety and Health Administration. (1999). OSHA technical manual (OTM): Controlling occupational exposure to hazardous drugs. Retrieved from http://www.osha.gov/dts/osta/otm/otm_vi/otm_vi_2.html

Polovich, M. (2011). Safe-handling of hazardous drugs. Pittsburgh, PA: Oncology Nursing Society.

Polovich, M., & Clark, P.C. (2010). Nurses’ use of hazardous drug safe handling precautions. Retrieved from http://digitalarchive.gsu.edu/nursing_diss/21

Polovich, M., & Clark, P.C. (2012). Factors influencing oncology nurses’ use of hazardous drug safe-handling precautions [Online exclusive]. Oncology Nursing Forum, 39, E299–E309.

Polovich, M., & Martin, S. (2011). Nurses’ use of hazardous drug-handling precautions and awareness of national patient safety guidelines. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38, 718–726.

Sammer, C.E., Lykens, K., Singh, K.P., Mains, D.A., & Lachan, N.A. (2010). What is patient safety climate? A review of the literature. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 42, 156–165.

Sessink, P.J., Connor, T.H., Jorgenson, J.A., & Tyler, T.G. (2010). Reduction in surface contamination in 22 hospital pharmacies in the U.S. following implementation of a closed system transfer device. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice, 17, 39–48.

Spratley, E., Johnson, A., Sochalski, J., Fritz, M., & Spencer, W. (2001). The registered nurse population, March 2000. Findings from the national sample survey of registered nurses. Retrieved from http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/rnsurveys/rnsurvey2000.pdf

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2010). The registered nurse population: Findings from the 2008 national sample survey of registered nurses. Retrieved from http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/rnsurveys/rnsurveyfinal.pdf

Valanis, B., McNeil, V., & Driscoll, K. (1991) Staff members’ compliance with their facility’s antineoplastic drug handling policy. Oncology Nursing Forum, 18, 571–576.

Valanis, B., Vollmer, W.M., & Steele, P. (1999). Occupational exposure to antineoplastic agents: Self-reported miscarriages and stillbirths among nurses and pharmacists. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 41, 632–638.

Valanis, B.G., Vollmer, W.M., Labuhn, K.T., & Glass, A.G. (1993). Acute symptoms associated with antineoplastic drug handling among nurses. Cancer Nursing, 16, 288–295.

Yodaiken, R.E., & Bennett, D. (1986). OSHA work-practice guidelines for personnel dealing with cytotoxic (antineoplastic) drugs. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 43, 1193–1204.

About the Author(s)

Callahan is a nurse manager in the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center at the Thomas Jefferson University Hospital in Philadelphia, PA; Ames is a research specialist in the Nursing Department at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Bethesda, MD; Manning is an associate professor in the School of Nursing at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia; and Touchton-Leonard is a research assistant, Yang is a biostatistician, and Wallen is deputy chief nurse, all in the Nursing Department at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. This research was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. Callahan, Ames, Manning, and Wallen contributed to the conceptualization and design. Callahan completed the data collection. Callahan and Yang provided statistical support and contributed to the analysis. Callahan and Touchton-Leonard contributed to the manuscript preparation. Callahan can be reached at amy.callahan@jefferson.edu, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org. Submitted September 2015. Accepted for publication November 10, 2015.