Patients’ Perspectives on Creating a Personal Safety Net During Chemotherapy

Nurses are critical to the physical management and psychological support of patients undergoing chemotherapy, which is a vulnerable time for many. This article presents the results of a qualitative study intended to explore the experience of Japanese patients with breast cancer during chemotherapy, including the finding that participants created personal safety nets in physical, emotional, and social contexts that helped them to gain confidence in their ability to exert control over their lives. Understanding each patient’s personal safety net allows nurses to support their patients in maintaining and improving their function and well-being.

At a Glance

- Patients with cancer create personal safety nets in physical, emotional, and social contexts during chemotherapy.

- Nurses can reduce patients’ distress, strengthen their safety nets, and empower them to lead meaningful lives.

- Nursing care should serve as a safety net for patients undergoing chemotherapy and promote the feeling of safety.

Jump to a section

Although chemotherapy may improve survival in patients with breast cancer, patients may experience a range of distressing side effects and suffer from psychosocial consequences of the disease and its treatment. Previous studies have reported that women with breast cancer who received chemotherapy had low vitality, as well as experienced restrictions in performing activities of daily living and fulfilling social and family roles (Barnes, Robert, & Bradley, 2014; Binkley et al., 2012; Fangel, Panobianco, Kebbe, de Almeida, & Gozzo, 2013; Ho, So, Leung, Lai, & Chan, 2013; Nizamli, Anoosheh, & Mohammadi, 2011). Cognitive changes related to cancer treatment affect self-esteem, self-confidence, and social relationships (Von Ah, Habermann, Carpenter, & Schneider, 2013). Chemotherapy may affect a woman’s life so significantly that she may feel as though side effects have taken control of her life (Pedersen, Koktved, & Nielsen, 2013).

In Japan, breast cancer is the most prevalent malignancy affecting women (Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research, 2015). Nurses must understand the impact of chemotherapy for breast cancer on patients’ lives. This article presents the results of a qualitative study conducted by the authors to explore the experiences of patients with breast cancer who had received chemotherapy to understand how they perceived the impact of the treatment on their daily lives.

Methods

This qualitative study used a grounded theory approach to explore the experiences of patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy. In this study, the grounded theory approach focused on social processes and generated a theory grounded in the reality of the participants’ daily life experiences (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Purposive sampling was conducted, followed by theoretical sampling based on the findings. Data analysis and further data collection were conducted simultaneously until no new themes emerged.

Participants were recruited from a list of outpatients with breast cancer who had undergone chemotherapy at breast or oncology center clinics at St. Luke’s International Hospital in Tokyo, Japan. The inclusion criteria were (a) diagnosis of breast cancer, (b) having received more than one cycle of chemotherapy to treat breast cancer, and (c) medical and psychological suitability for interview, confirmed by the physician. Exclusion criteria were (a) initial diagnosis of advanced cancer, (b) the need for treatment of cognitive impairment as determined by a physician, and (c) significant physical or psychological discomfort. To ensure voluntary participation, outpatient nurses explained the study to eligible women and asked whether they wished to receive additional information. Those who were interested in the study met with one of the authors on a date (the day of recruitment or next appointment) set with the outpatient nurse and received oral and written explanations of the purpose of the research and a description of the procedure.

This study was approved by the internal review boards of the Faculty of Nursing and Medical Care at Keio University (No. 209) and St. Luke’s International Hospital (13-R044). Written and oral informed consent were obtained from all participants. All individual interviews were conducted by a current author at St. Luke’s International Hospital from August 2013 to September 2014. A semistructured interview guide was used, and each interview lasted 30–50 minutes.

Data Analysis

Interviews were recorded and transcribed. The transcripts were analyzed using the following process. Data were coded, and the meanings were labeled. Subcategories, originating from coding, were identified to lead categories. A core category (main theme) emerged by connecting the categories and subcategories. For credibility and dependability, two of the authors reviewed the data to determine whether they agreed with the codes and categories identified. The authors confirmed that no new themes emerged after the 17th interview had been conducted. For confirmability, one of the authors performed an analysis, and another confirmed the codes, categories, and core category identified in the analysis. Subsequent to identification of the themes and their supporting quotations, a professional translator translated them into English.

Results

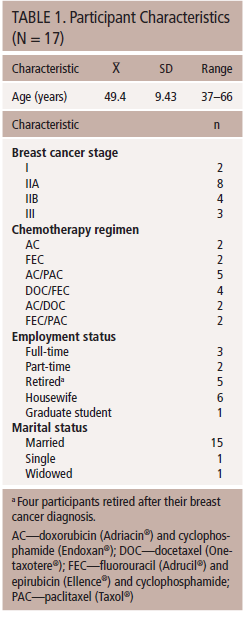

Participants’ characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Of 21 women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer who were informed about the study, 17 chose to participate. The participants, who had a mean age of 49.4 years, had experienced distress and loss of control because of the disease and chemotherapy. However, they focused on what they were able to do during chemotherapy and created personal safety nets in physical, emotional, and social contexts to gain confidence in their ability to exert control over their lives. Creation of a personal safety net, which built a foundation for a positive life, emerged as a main theme in the relationships between categories and subcategories. The three categories, with their subcategories in parentheses, are as follows: (a) distress (loss of control); (b) personal safety net: confidence in control over life (defense behaviors, maintaining daily routines, support from others); and (c) my precious life (reevaluation of benefits, positive approach).

Distress

Loss of control: The participants reported that their lives were suddenly disturbed and became uncertain with the diagnosis of cancer. Participants were overwhelmed and sad.

I was depressed and lost my appetite when I heard the result of the test. . . . People of my age have the notion that cancer leads to death.

I was depressed. Maybe I was too sensitive and overreacted. I was irritated by small things. I couldn’t think about anything else.

In addition, the participants experienced a wide range of side effects, including fatigue, nausea, and hand numbness, during chemotherapy. These symptoms restricted their daily activities, and they experienced a loss of control. One participant reported having difficulty just walking through her house, whereas another participant said that the numbness made taking coins out of her purse while shopping difficult.

Probably because I was psychologically weak, I thought I knew what to expect, but I totally lost control.

Despite great variability, some participants experienced mild cognitive impairment, which they referred to as an “empty head” and “fog” that affected their concentration. The participants also said they felt isolated as they experienced changes in their daily lives and relationships with others.

I used to work every day, so I met people and talked to them. But my everyday life was suddenly shut down. I was confined to my house. I was depressed, lonely, and tearful.

I felt like my illness experience was fading from the memories of people around me. I felt empty inside and still had some fear. The feeling of disappearing from the memories of people became stronger and stronger, and I was cluttered up with it.

Personal Safety Net: Confidence in Control Over Life

The participants created personal safety nets during chemotherapy. Physically, they saved their energy by restricting their activities. Emotionally, they found comfort in normal life and concentrated on what they were able to do in their daily lives. They gained confidence in their ability to exert control over their lives by maintaining daily routines and completing tasks. In addition, they felt that life was worth living when they did something for someone else.

Defense behaviors: Several participants referred to the state of chemotherapy as “hibernation” and worked to prepare for it. After beginning chemotherapy, they attempted to reduce their activity and rest to save energy while waiting for the side effects to subside. Some participants asked family members to help them or arranged a helper service, whereas others ceased work during chemotherapy.

I thought I’d better concentrate on my treatment and hibernate during chemotherapy.

Maintaining daily routines: The participants acknowledged the importance of performing daily tasks, even though they felt unwell and their function was limited. Participants said they wanted to fulfill their roles and take care of others at home.

If I was able to do only one thing, even though I did not feel well, that was good enough. I did not want to eat, but I cooked because there was someone to cook for.

Support from others: The majority of the participants reported that they were supported by people, such as family members, friends, and peers, who cared for them.

When my son said to me, “You will be okay because you are my mommy,” it encouraged me very much. He supported me psychologically.

My Precious Life

Reevaluation of beliefs: The participants looked back on the past from a present with cancer and frequently reevaluated their beliefs. They decided to change some of their behaviors to remain as healthy as possible.

Nothing is worth it if I am not alive. Now I know how important good health is, so I think that this is a part of my life, and I am clear about it.

Before I underwent treatment, I used to stay up all night, and I worked hard, even when I felt tired, but because I have experienced a serious illness, I no longer do it.

The participants said they realized the importance of each day and were determined to enjoy their lives.

But because of the experience of illness, I realize how precious each day and normal life is.

Positive approach: Once the participants gained confidence in having control over their lives, they sought positivity. They took a positive approach to making their lives enjoyable and meaningful despite the cancer. Some participants started something new and succeeded in doing so.

I still have anxiety and fear about recurrence and metastasis, but I am much better now compared to the condition I was in when I was hospitalized for low liver function. I am okay because I can move now and I am still alive. I am a positive thinker now. That’s the biggest change.

I have various side effects, but I think I’d better be positive because tomorrow is coming.

Discussion

The patients with cancer who took part in the current study created personal safety nets in physical, emotional, and social contexts during chemotherapy, even though they found everyday life to be more difficult because of the disease and side effects. Through their safety nets, the participants felt more confident and in control of their lives, and were willing to take a positive approach toward making their lives meaningful.

These findings highlight the importance of the personal safety net. When patients with cancer are at risk of distress, they need to seek a secure environment in which they feel safe. In anticipation of the side effects of chemotherapy, participants “hibernated” and expended a minimal amount of energy. They also created a protective inner space in which they were able to tolerate fear and anxiety and exert self-control. The participants in this study found safe places within their daily lives and emphasized their commitment to maintaining their daily routines. Performing daily tasks provided them with the comfort and confidence they needed to balance their lives and illness and helped them to tolerate uncertainty. Pederson et al. (2013) reported that patients tried to find their own way to maintain a sort of normality in everyday life.

Great variability existed in participants’ perceptions of side effects, particularly cognitive impairment, which is consistent with previous studies. Cognitive changes significantly affected patients’ daily lives (Cheung et al., 2012), but individual differences were noted (Rust & Davis, 2013). In the current study, participants tested the boundaries of their new limitations and potential via the personal safety net. Personal control needs, including those of autonomy and independence, have been found to be high in patients with cancer (Burg et al., 2015). Rather than being protected by family, the participants in this study wanted to fulfill their roles at home, even if this was only one small role, and one of the participants commented that she found it very helpful to be treated as usual by her family.

Conclusion

The current study identified the personal safety net as the underlying process of personal transformation, a concept from positive psychology, in women with breast cancer. A number of studies have also reported the reevaluation of beliefs and personal transformation as a means of adapting to life changes (Sandsund, Pattison, Doyle, & Shaw, 2013; Skeath et al., 2013; Young, Nadarajah, Skeath, & Berger, 2015). In one study, some patients who received chemotherapy decided not to return to work following reassessment of their life goals and decided instead to participate in society in other ways (van Muijen et al., 2013). Women with breast cancer also have described reconstructing their lives after the diagnosis and mentioned becoming more independent (Fangel et al., 2013).

Providing patients with a pathway for access to needed information is important for patients who experience psychological symptoms (Lewis et al., 2015). Nurses can provide support to patients undergoing chemotherapy not only by increasing patients’ knowledge and symptom management but also by understanding the effects of treatment on patients’ daily lives and concerns. Nurses can reduce patients’ distress, teach coping strategies, and develop effective interventions that enable patients with cancer to maintain and improve their physical, emotional, and social functions during and after chemotherapy.

Because few studies have explored patients’ perspectives regarding the impact of chemotherapy on their daily lives, the current study complements existing quantitative literature seeking means of supporting patients undergoing chemotherapy, despite the small study size and limited generalizability of the results. Nurses need to understand the process from distress to personal transformation via the personal safety net and help patients to use the personal safety net as a step toward positive personal transformation during and after the treatment process. Nursing care should serve as a safety net for patients undergoing chemotherapy and promote the feeling of safety.

References

Barnes, A.J., Robert, N., & Bradley, C.J. (2014). Job attributes, job satisfaction and the return to health after breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Psycho-Oncology, 23, 158–164. doi:10.1002/pon.3385

Binkley, J.M., Harris, S.R., Levangie, P.K., Pearl, M., Guglielmino, J., Kraus, V., & Rowden, D. (2012). Patient perspectives on breast cancer treatment side effects and the prospective surveillance model for physical rehabilitation for women with breast cancer. Cancer, 15(Suppl. 8), 2207–2216. doi:10.1002/cncr.27469

Burg, M.A., Adorno, G., Lopez, E.D., Loerzel, V., Stein, K., Wallace, C., & Sharma, D.K. (2015). Current unmet needs of cancer survivors: Analysis of open-ended responses to the American Cancer Society Study of Cancer Survivors II. Cancer, 121, 623–630. doi:10.1002/cncr.28951

Cheung, Y.T., Shwe, M., Tan, Y.P., Fan, G., Ng, R., & Chan, A. (2012). Cognitive changes in multiethnic Asian breast cancer patients: A focus group study. Annals of Oncology, 23, 2547–2552. doi:10.1093/annonc/mds029

Fangel, L.M.V., Panobianco, M.S., Kebbe, L.M., de Almeida, A.M., & Gozzo, T.O. (2013). Qualify of life and daily activities performance after breast cancer treatment. Acta Paulista de Enfermagem, 26, 93–100.

Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research. (2015). Cancer statistics in Japan—2014. Retrieved from http://ganjoho.jp/data/reg_stat/statistics/brochure/2014/cancer_statist…

Ho, S.S., So, W.K., Leung, D.Y., Lai, E.T., & Chan, C.W. (2013). Anxiety, depression and quality of life in Chinese women with breast cancer during and after treatment: A comparative evaluation. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17, 877–882. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2013.04.005

Lewis, L., Williams, A.M., Athifa, M., Brown, D., Budgeon, C.A., & Bremner, A.P. (2015). Evidence-based self-care guidelines for people receiving chemotherapy: Do they reduce symptom burden and psychological distress? Cancer Nursing, 38, E1–E8. doi:10.1097/NCC.0000000000000154

Nizamli, F., Anoosheh, M., & Mohammadi, E. (2011). Experiences of Syrian women with breast cancer regarding chemotherapy: A qualitative study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 13, 481–487. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2018.2011.00644.x

Pedersen, B., Koktved, D.P., & Nielsen, L.L. (2013). Living with side effects from cancer treatment—A challenge to target information. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 27, 715–723. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01085.x

Rust, C., & Davis, C. (2013). Chemobrain in underserved African American breast cancer survivors: A qualitative study. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17, E29–E34. doi:10.1188/13.CJON.E29-E34

Sandsund, S., Pattison, N., Doyle, N., & Shaw, C. (2013). Finding a new normal: A grounded theory study of rehabilitation after treatment for upper gastrointestinal or gynaecological cancers—The patient’s perspective. European Journal of Cancer Care, 22, 232–244. doi:10.1111/ecc.12016

Skeath, P., Norris, S., Katheria, V., White, J., Baker, K., Handel, D., . . . Berger, A. (2013). The nature of life-transforming changes among cancer survivors. Qualitative Health Research, 23, 1155–1167. doi:10.1177/1049732313499074

Strauss, A.L., & Corbin, J.M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

van Muijen, P., Weevers, N.L., Snels, I.A., Duijts, S.F., Bruinvels, D.J., Schellart, A.J., & van der Beek, A.J. (2013). Predictors of return to work and employment in cancer survivors: A systematic review. European Journal of Cancer Care, 22, 144–160. doi:10.1111/ecc.12033

Von Ah, D., Habermann, B., Carpenter, J.S., & Schneider, B.L. (2013). Impact of perceived cognitive impairment in breast cancer survivors. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 17, 236–241. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2012.06.002

Young, W.C., Nadarajah, S.R., Skeath, P.R., & Berger, A.M. (2015). Spirituality in the context of life-threatening illness and life-transforming change. Palliative and Supportive Care, 13, 653–660. doi:10.1017/S1478951514000340

About the Author(s)

Hiroko Komatsu, PhD, RN, is a professor and Kaori Yagasaki, PhD, RN, is an associate professor, both in the Faculty of Nursing and Medical Care at Keio University, Hideko Yamauchi, MD, is the director of the Breast Center and Teruo Yamauchi, MD, is the chief of the Division of Medical Oncology, both at St. Luke’s International Hospital, all in Tokyo, Japan. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the article. Komatsu was supported by a research grant from Health Labour Sciences Research (Grant ITAKUHI) and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. No financial relationships relevant to the content of this article have been disclosed by the editorial staff. Mention of specific products and opinions related to those products do not indicate or imply endorsement by the Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing or the Oncology Nursing Society. Komatsu can be reached at hkomatsu@sfc.keio.ac.jp, with copy to editor at CJONEditor@ons.org.