Timing and Mode of Breast Care Nurse Consultation From the Patient’s Perspective

Objectives: To understand what, if any, differences exist in the perception of a breast care nurse (BCN) consultation between women who experienced a preoperative, face-to-face counseling and education opportunity with a BCN, and those who required a telephone consultation or were unable to experience a preoperative BCN consultation.

Sample & Setting: A convenience sample of women in a private hospital in Western Australia who had breast surgery for breast cancer, BRCA gene mutation, or breast cancer risk reduction, and who experienced face-to-face contact, telephone contact, or no preoperative contact with a BCN.

Methods & Variables: A single-center, mixed-methods, descriptive study comparing timing and mode of consultation.

Results: Women who experienced a timely face-to-face consultation with a BCN in the preoperative period reported that they received superior education and emotional and practical support than women who experienced a telephone consultation or postoperative consultation with a BCN.

Implications for Nursing: When a patient’s circumstances allow, a consultation with a BCN in the preoperative period should be offered. Ideally, this consultation should be conducted face-to-face to provide the education and psychosocial and practical support that patients undergoing breast surgery require. When this is not possible, a telephone consultation should be offered, as opposed to waiting until after surgery.

Jump to a section

Globally, breast cancer is the most common cancer among women, and its incidence is increasing (Ferlay et al., 2015). Cancer Australia (2017a) estimates that 17,586 new cases of breast cancer were diagnosed in Australian women in 2017. With increasing demands on breast cancer services, determining optimal treatment and support is required to ensure that high-quality holistic care is provided to patients. When a woman receives a breast cancer diagnosis, she and her family members are faced with making decisions regarding treatment while trying to cope with complex feelings (Browall, Kenne Sarenmalm, Persson, Wengström, & Gaston-Johansson, 2016; Çömez & Karayurt, 2016). Further compounding this is the often short period from diagnosis to the commencement of treatment, which gives women little time to take in the information presented to them and process their feelings (Cordeiro, Dixon, Coburn, & Holloway, 2015; Dickerson, Alqaissi, Underhill, & Lally, 2011). The psychological distress that women experience during this time is well recognized (Fox et al., 2013), and many strategies have been developed to help them through their breast cancer journey. One of these strategies, implemented in the 1990s in Australia, was the inclusion of a breast care nurse (BCN) in a patient’s healthcare team, as a stand-alone clinician or within another model of care (Porter-Steele, Tjondronegoro, Seib, Young, & Anderson, 2017).

The current study site, St. John of God Subiaco Hospital in Western Australia, employs a breast care clinical nurse consultant 21 hours per week and a breast care clinical nurse 14 hours per week, covering all five weekdays, and has done this for the past five years. The annual caseload of women undergoing breast surgery is 200–250 per year, depending on the availability of a surgeon. In addition to patients who are directly referred, the BCN attempts to see every patient who comes through the outpatient clinics. The opportunity to arrange a preoperative BCN consultation before admission to the hospital prior to surgery is related to a surgeon’s preference, time constraints from the surgical consultation to the surgery date, and the availability of the BCN. Anecdotally, BCNs at the study site observed that patients who have not had a preoperative consultation with a BCN present with increased anxiety and distress.

When a patient is admitted preoperatively on the morning of surgery, the BCN attempts to provide education and counseling; however, this is of limited value because of the patient’s anxiety and the time constraints. Patients often need to have preoperative procedures undertaken in radiology and their admission completed by the ward nursing staff to be ready for surgery, both of which impose on the amount of time available for the BCN to provide preoperative education and counseling. Some surgical procedures are day cases, and these patients may not have the opportunity to see the BCN preoperatively. BCNs at the study site reported that these patients appear to exhibit greater psychological distress as a result of insufficient or no preoperative education and counseling and, subsequently, require longer postoperative BCN consultations as an inpatient. In addition, they often require more frequent postdischarge BCN telephone contact. In this context, and with no evidence to direct the timing or mode of BCN consultation, the current research explored women’s experiences of a consultation with a BCN as part of their admission for breast cancer treatment.

The National Breast Cancer Centre clinical practice guidelines for the management of early breast cancer initially were released by the National Health and Medical Research Council in October 1995. In 2001, the second edition recommended that women living in Australia who were diagnosed with breast cancer have access to support provided by a BCN (National Breast Cancer Centre, 2001). The role of a BCN, described in the clinical practice guidelines, is to provide ongoing counseling, information, and support; to clarify or reinforce information; to provide continuity of care throughout the treatment process; and to facilitate liaison and referral to other healthcare professionals (National Breast Cancer Centre, 2001). BCNs are ideally placed to support patients at the time of their diagnosis, during their treatment, and into their surviving years (Ahern, Gardner, & Courtney, 2015).

Despite widespread implementation of the role across Australia following the 2001 recommendation, a review of the literature found that this role has not been well evaluated (Ahern & Gardner, 2015), meaning that the true value of the BCN role is unknown. However, Halkett, Arbon, Scutter, and Borg (2006) have reported the importance that patients place on the BCN role while they are being treated; they described how patients found BCNs to provide important support throughout their treatment. Luck, Chok, Scott, and Wilkes (2017) described the importance of the BCN role from the perspective of BCNs, highlighting the part they play in sharing clinical expertise through providing patient education, coordinating care, and advocating for patients. However, the study failed to explore the patient perspective of receiving BCN support, which may differ from the perspective of BCNs delivering support. Dickerson et al. (2011) investigated the experience of women from diagnosis to surgery, finding that women’s needs are individual and varied, but that the main goal for women during that time is survival. What is not reported in the literature is how BCNs can best provide support during this time, and which mode of consultation ideally should be available to patients.

The current study’s objective was to demonstrate what, if any, differences exist in the patient perception of a BCN consultation with respect to the mode and timing of the consultation. Specifically, the focus was the difference between women who experienced a preoperative, face-to-face counseling and education opportunity with a BCN (cohort 1), compared to those whose situation required a telephone consultation (cohort 2). In addition, the study explored the perceptions of patients who were unable to experience a preoperative consultation with a BCN (cohort 3) compared to patients who were able to access this opportunity.

Methods

Design and Sample

A single-center, mixed-methods descriptive study was undertaken, with the emphasis being on the quantitative data and the qualitative data being used to support the research findings (Driessnack, Sousa, & Mendes, 2007). In this way, the research design reflected a QUAN/qual design, as described by Johnson and Christensen (2012).

A convenience sampling approach was used to recruit 67 women who had breast surgery and had face-to-face contact (cohort 1, n = 27), telephone contact (cohort 2, n = 20), or no preoperative consultation with the BCN (cohort 3, n = 20). Mode of consultation, or lack thereof, was dependent on patient and BCN availability and affected by real-life situations not determined by the study. Patients were recruited from April 2015 to January 2017. All women who were scheduled for breast surgery at the study site following a diagnosis of breast cancer, for a BRCA gene mutation, or for breast cancer risk reduction were invited to participate. Patients who had delayed breast reconstruction or revisional surgery related to postoperative complications or poor cosmesis were excluded. The project was evaluative in nature, and measuring the effect of an intervention was not the purpose of the current research; the study did not intend to statistically test between-group outcomes or to generalize the findings to a larger population.

Data Collection and Instrument

The current study used a tool previously used and reported in the literature to assess the effectiveness of a BCN in supporting women with breast cancer by surveying, via telephone, women who received care from a BCN or did not receive care from a BCN (Eley & Rogers-Clark, 2012; Eley, Rogers-Clark, & Murray, 2008). The questionnaire related to coordination of care offered and the value and timing of information and support during treatment. The questionnaire used a Likert-type scale with a three- to five-point range, depending on the question. Higher scores indicated more positive agreement with the question or statement, and lower scores indicated that respondents did not agree with the question or statement. An opportunity for additional comments also was provided. In the case of patients who experienced a BCN consultation, one open-ended question at the end of the questionnaire was: “Do you have any other comments?” For patients who did not receive a consultation with a BCN, the two open-ended questions were as follows:

• “Do you believe that having support from a BCN would have been helpful? In what way?”

• “Do you have any other comments?”

Permission to use the questionnaire was granted from the original authors (Eley et al., 2008). Slight modifications were undertaken to suit the study (e.g., state-appropriate nomenclature), and a section was added to collect biographic and demographic data, including age, dependents, support person, employment status, home location, surgery or treatment regimen, and length of stay. Given that the questionnaire had no major changes from the original tool and that the original tool had been reported in the literature (Eley & Rogers-Clark, 2012), a pilot study was not conducted.

A paper copy of the questionnaire was given to women who met the inclusion criteria. For patients who experienced a consultation with the BCN, the questions reflected that, using wording such as the following:

• “How would you rate the amount of help from the BCN?”

• “Do you believe that the BCN . . . ?”

For patients who were not able to see the BCN, the questionnaire reflected this, with questions such as the following:

• “How would you rate the amount of help you received from the service or organization?”

• “Do you believe that the contact . . . ?”

The questionnaire, relative to a patient’s situation (e.g., face-to-face or telephone preoperative consultation or no preoperative consultation with the BCN), was distributed at the postoperative appointment, which was one to three weeks postsurgery, with a reply paid envelope. If the BCN was unavailable at the time of the postoperative appointment, the patient was contacted by telephone (normal protocol), and permission to send a questionnaire was sought. The information sheet was addressed from the nursing and midwifery research coordinator, and the reply paid envelope was addressed back to her to maximize independence from the BCN.

Data Analysis

Demographic data were entered into Microsoft® Excel, and the features of the software were used to analyze the closed-ended questions. The qualitative data (provided in response to open-ended questions) underwent a general thematic analysis. A reductive method of content analysis was employed to identify themes or patterns and common categories (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). All three researchers independently analyzed the data before they joined to discuss and reach consensus on the final themes (Schneider, Whitehead, Lobiondo-Wood, & Haber, 2016).

Ethical Considerations

The recruitment and data collection commenced after approval from the Human Research Ethics Committee at St. John of God Health Care and Curtin University. Respondents were provided with an information sheet, and return of the questionnaire implied consent to participate in the study. The project included a three-stage distress protocol in the event that involvement in the project caused distress. Initial management of the distress was conducted by the BCN. If respondents experienced ongoing distress, they would be referred to the pastoral care service for a one-off consultation with a pastoral practitioner, with subsequent referral to a community organization if indicated (e.g., Cancer Council Australia).

Results

Quantitative Data

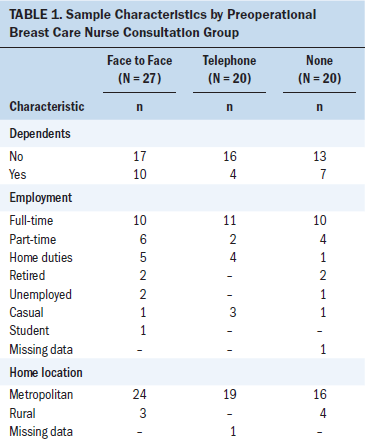

A total of 88 questionnaires were distributed to patients meeting the inclusion criteria. A response rate of 76% (n = 67) was achieved, without the use of a reminder or the deployment of other follow-up strategies. All respondents were female, with a mean age of 58 years. The demographic profile of respondents is presented in Table 1. Of the 67 respondents, 27 saw the BCN in a face-to-face consultation (cohort 1, mean age = 58 years, range = 41–88), 20 experienced a telephone consultation with the BCN (cohort 2, mean age = 57 years, range = 38–82), and 20 were not able to have a consultation with the BCN in the preoperative period (cohort 3, mean age = 57 years, range = 46–72). The mode of consultation was not overtly influenced by a respondent’s age, employment status, place of residence, or surgery type.

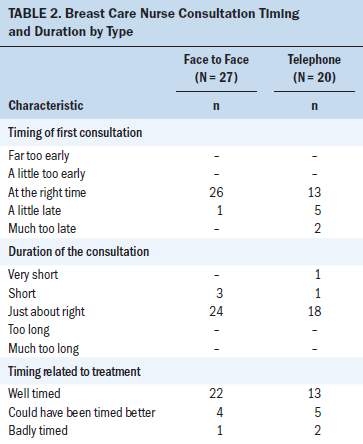

Respondents who received a BCN consultation perceived a face-to-face consultation to be at a more appropriate time and better timed with respect to their treatment than a telephone consultation (see Table 2). Respondents who did not have a preoperative consultation with the BCN (n = 4) reported that they were not referred to any specific individual or support organization. For those who were referred onward for support, the predominant source of information was the surgeon (n = 11), followed by the state (n = 7) and national breast cancer centers (n = 5), with many respondents accessing more than one source of support. Respondents contacted these individual surgeons or organizations at least once (n = 2) but mostly twice (n = 5), although some respondents made contact three to five times (n = 4). When a respondent was able to see the BCN face-to-face, the level of satisfaction was highest, followed by those who had a preoperative telephone call with the BCN, then those who had contact with another person or organization.

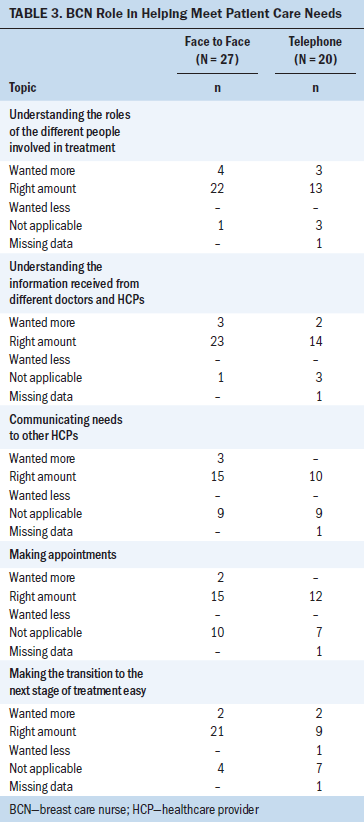

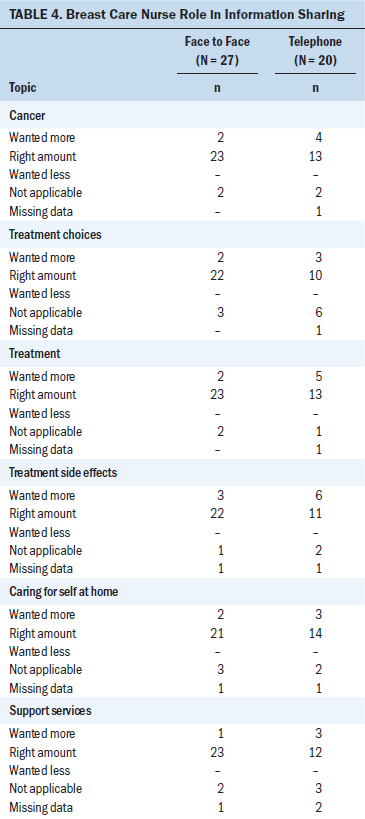

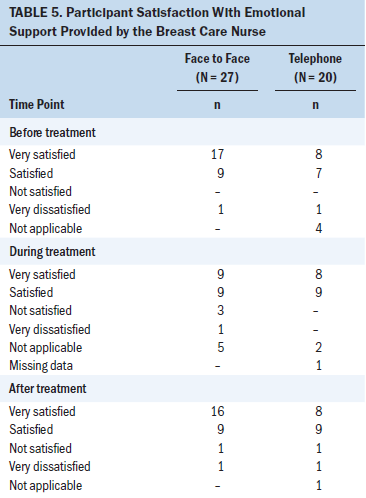

With respect specifically to a BCN consultation, face-to-face or via telephone, little difference was seen in how respondents rated the amount of help they received in most areas (see Table 3), except for the transition to the next stage, for which a face-to-face consultation more frequently provided the right amount of information (n = 21) than a telephone consultation (n = 9). In contrast, respondents who experienced a face-to-face consultation were more likely to rate the amount of information they received about their cancer and treatment from the BCN as the “right amount” than those who experienced a telephone consultation (see Table 4). Regardless of the mode of contact with the BCN, most respondents agreed that the BCN was capable and supportive before, during, and after treatment (see Table 5); four respondents who experienced a telephone consultation did not consider this aspect of the BCN role to be applicable in the preoperative period. Finally, the mode of contact did not make a difference to whether a respondent would recommend a hospital with a BCN to a friend, with most respondents (n = 42) agreeing that a hospital with access to a BCN is preferable to one without.

Qualitative Data

The current study used a questionnaire with a predominantly quantitative approach; respondents provided a large amount of data in the open-ended questions fields. The following three themes were identified from open-ended questions:

• Providing knowledge for understanding

• Psychosocial support

• Practical support

Providing knowledge for understanding: The first theme reflected the need expressed by respondents to receive information to understand their diagnosis and treatment options. Respondents reported that the BCN gave information in a way that was easily understood. This theme was consistent for respondents who received a face-to-face consultation and for respondents who received a telephone consultation. One respondent who received a telephone consultation described this in terms of how her confidence about decisions was boosted: “She made me feel more confident about the decisions regarding my course of treatment. After speaking with her, I knew the decisions I had made were right.” Respondents also reported that the BCN provided holistic information, suitable for the respondents and their support people. According to one participant who received a face-to-face consultation, “[I] found the nurse to be very helpful—answered many questions asked by myself and my partner. Was very understanding and checked to make sure we understood the information she was giving.”

Respondents who did not receive any form of preoperative consultation were able to recognize that this would have helped them understand what was about to happen, were it available to them. One respondent said, “Before surgery would have been fabulous to have talked to her. I didn’t fully understand the procedure I needed on the day of surgery, so it was a shock—would have made a big difference.” It was clear that a preoperative face-to-face or telephone consultation provided an opportunity to answer questions and clarify respondents’ understanding of their diagnosis and course of treatment. Respondents who were unable to have a preoperative consultation lacked understanding of their surgical procedure.

Psychosocial support: The second theme revealed that respondents have specific emotional and psycho-logical needs in the time leading up to their breast surgery that the BCN was able to support. The support helped respondents manage and understand their feelings, as stated by one participant who received a face-to-face consultation: “My [BCN] really made me feel like she was genuinely there to support me through whatever I needed during this process. . . . I think it gave me confidence and helped me feel positive, which I believe helps with recovery.”

The respondents reported that the BCN was empathetic toward them during their consultations and that this was appreciated. According to one participant who received a telephone consultation, “It was great to have someone that understood my anxiety.” As with the first theme, respondents who did not have a preoperative consultation demonstrated the impact of this and were able to articulate the difference they felt a consultation would have made to them, if it had been available. One participant who did not have a preoperative consultation said, “I could have been better prepared for surgery emotionally, had I spoken to the BCN prior to the operation.”

Respondents who had a face-to-face or telephone consultation felt supported and had an opportunity to share emotions, creating confidence in their recovery. Those who were unable to have a preoperative consultation expressed feelings of being overwhelmed and confused and wished they had a professional listener, as expressed by one participant: “It would have been great to have someone who ‘had my back’ and could listen, inform, reassure, and understand what I was going through.”

Practical support: The final theme covered the practical support that the BCN was able to provide to respondents from the time of their diagnosis to surgery; the support also was relevant to the postoperative period. In some instances, this advice was about personal aids (e.g., prostheses, support brassieres), and, at other times, this practical support was regarding help available from other sources and organizations. One respondent who received a telephone consultation said, “She offered to introduce me to a group that could help me get back to more normal life, and if it were not for her, I [would have] had no idea this group existed. I owe her a big thank-you.”

Respondents were able to recognize that this support is possibly unique to the BCN service, which was conveyed by one participant who received a face-to-face consultation: “I was given information and tips I might otherwise not have received.” As with the other two themes, respondents who did not have access to the BCN felt that this may have been detrimental to their experience. One participant said, “I would have benefited from seeing a nurse before my procedure. Lots I didn’t know and wasn’t prepared for.” Respondents who did not have a preoperative consultation wanted to be prepared and were surprised at the lack of information compared to those who did have a preoperative consultation and were appreciative of the advice provided.

In addition to the three themes identified across the three cohorts, the researchers found that respondents who received a telephone consultation indicated that they would prefer a face-to-face consultation to a telephone consultation. One participant who received a telephone consultation said, “It would have probably been much better if I met her face-to-face before surgery rather than just a phone call.” According to another participant who received a telephone consultation, “I feel it would be beneficial for all [preoperative] patients to have a face-to-face consultation because they would be shown what drains are, what a catheter is, etc. I feel this would alleviate fear of [postoperative] expectations. Also, a familiar face [is] so wonderful to have in [the] hospital.” These findings are consistent with the findings from the survey data.

Discussion

The mean age of each cohort (58 years for the face-to-face cohort and 57 years for telephone and no preoperative consultation cohorts) is representative of the wider Australian population, with 75% of new cases of breast cancer developing in women aged older than 50 years (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014). The demographic data collected indicated no differences among the three cohorts studied. The homogeneity of the three cohorts provides increased confidence that the differences observed were because of the different types of consultations received rather than varying characteristics of the cohorts. Recruitment took longer than originally anticipated because of difficulties meeting inclusion criteria and filling the required number of participants for the no preoperative consultation cohort.

Timing of the Consultation

As previously discussed, the BCN is an important member of the team caring for patients with breast cancer (Porter-Steele et al., 2017). What has not previously been reported is the impact of the timing of a consultation. At the study site, patients were offered a telephone consultation when time from surgical consultation to admission was insufficient to permit a face-to-face consultation. With respect to timing of the first consultation with a BCN, respondents who received a face-to-face consultation felt this was more appropriate than respondents who received a telephone consultation. In addition, the timing of the consultation, with respect to the treatment that followed, was reported to be superior in respondents who experienced a face-to-face consultation compared to those who received a telephone consultation. Despite these differences, the majority of respondents were satisfied with the duration of their consultation, regardless of the mode of consultation (face-to-face or via telephone).

Women with breast cancer continue to have unmet needs in their physical and emotional care and knowledge (Akechi et al., 2011; Fiszer, Dolbeault, Sultan, & Brédart, 2014; Watts et al., 2011). This study found that not receiving a preoperative consultation affected women in the areas of knowledge and psychosocial and practical support. The qualitative comments elucidate that these respondents felt that their confidence may have been higher and their overall experience better, had they had the opportunity for a preoperative consultation. This is similar to the findings of Eley and Rogers-Clark (2012), who found that receiving the support of a BCN improved patients’ perception of their care, quality of direct patient care, and continuity of care.

Consultation Mode

With respect to the mode of the consultation, respondents who had a face-to-face or telephone consultation felt more assured in their treatment choices, less anxious, and more confident in their recovery than respondents who did not have a preoperative consultation. Evidence in the literature suggests that higher levels of self-efficacy in patients with cancer are associated with improved quality of life and decreased psychological distress (Philip, Merluzzi, Zhang, & Heitzmann, 2013; Rottmann, Dalton, Christensen, Frederiksen, & Johansen, 2010). Respondents who experienced a face-to-face consultation reported it to be superior regarding the amount of information they received about their cancer and treatment from the BCN, compared to those who experienced a telephone consultation. Sharing knowledge and providing education are reported to be key aspects of the BCN role (Dickerson et al., 2011; Luck et al., 2017).

Face-to-face and telephone consultations provided an opportunity for preoperative support, with respondents stating that they were grateful for advice regarding postsurgical emotional care (such as access to support group information) and practical support (such as brassieres and prostheses). However, the current results demonstrate that respondents who had a telephone consultation felt that a face-to-face consultation preoperatively would have been preferable to alleviate fear of postoperative expectations. Although it is acknowledged that different women have different needs (Porter-Steele et al., 2017), the current findings support the provision of a face-to-face consultation when a BCN is included in a patient’s healthcare team.

It was clear that a preoperative consultation (face-to-face or via telephone) provided respondents an opportunity to answer questions and clarify their understanding of their diagnosis and course of treatment. Respondents who did not have a preoperative consultation tended to report a lack of understanding regarding their treatment, further illuminating the unmet needs of women (Akechi et al., 2011; Fiszer et al., 2014; Watts et al., 2011). In addition, respondents who did not receive a preoperative consultation had clear ideas of what a preoperative consultation with a BCN could have provided them, reporting that they felt they had missed out on an opportunity for further education and emotional and practical support (Ahern & Gardner, 2015; Luck et al., 2017).

Implications for Nursing

Evidence in the literature shows that the BCN is an integral member of the interprofessional team caring for patients undergoing breast surgery (Ahern & Gardner, 2015; Halkett et al., 2006; Luck et al., 2017). The current study suggests that the timing of a patient’s first consultation with a BCN and the mode of that consultation are determinants of the patient’s overall outcomes, particularly in the areas of understanding diagnosis and treatment, feeling psychosocially supported, and receiving relevant practical support. As such, the authors recommend that patients who are to be admitted for breast surgery, regardless of the reason, should be referred to a BCN for a face-to-face, preoperative consultation before admission. Early referral to a BCN and effective communication with the breast cancer treatment team is crucial. Ideally, the BCN should participate in the patient’s surgical consultation. BCN support commencing prior to surgery is essential to ensure holistic support from the beginning of the patient’s journey. Increased self-efficacy has been demonstrated to improve patient outcomes (Philip et al., 2013; Rottmann et al., 2010), and early involvement from the BCN can assist with this. To facilitate BCN involvement, organizations need to ensure sufficient numbers and availability of BCNs, and flexible working hours should be offered to enable all patients access to a BCN. If a patient is unable to attend a face-to-face consultation with a BCN, a telephone consultation should be scheduled with a BCN before admission. To further enhance telephone consultations, video calls could be used to enable visual communication.

Limitations

The current study had a small convenience sample comprised of only women, thereby introducing a selection bias (Polit & Beck, 2017). In reality, the recruitment of men would be time-consuming, given that only three men per week will be diagnosed with breast cancer in Australia (Cancer Australia, 2017b). In addition, the current study used a self-reported, retrospective design, introducing the potential for recall bias (Polit & Beck, 2017). The authors acknowledge that the small sample size and the fact that the study reports experiences from women who saw a BCN in one private hospital limit the generalizability of the findings. A dearth of evidence supporting the role of BCNs remains (Ahern & Gardner, 2015; Cruickshank, Kennedy, Lockhart, Dosser, & Dallas, 2008). Despite these limitations, the current study adds to the evidence of the importance of BCNs in the breast care journey, particularly with respect to the mode and timing of the consultation.

Conclusion

A preoperative consultation with a BCN reduces anxiety and provides an opportunity for education and counseling, enabling patients and their families to be informed, emotionally supported, and more confident in their recovery. A face-to-face consultation before surgery is preferable; however, if a patient is unable to attend a face-to-face consultation because of time restriction from surgical planning to hospital admission or because of other constraints, a telephone consultation will provide benefit. For women who are unable to access a BCN in the preoperative period, the BCN must attempt to address remaining unmet emotional and physical needs of women in the postoperative period.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the patients who took the time to complete and return their questionnaires and make comments on the consultation they received from the breast care nurse. Their feedback has been invaluable to this study and to the future provision of this service.

About the Author(s)

Janie Brown, PhD, is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Health Sciences at Curtin University in Bentley, Western Australia; Gay Refeld, BN, is a breast cancer clinical nurse consultant at St. John of God Subiaco Hospital in Western Australia; and Alannah Cooper, BSN, is a research nurse at St. John of God Subiaco Hospital and a clinical research nurse at Fiona Stanley Hospital in Murdoch, Western Australia. No financial relationships to disclose. Brown and Refeld contributed to the conceptualization and design. All authors completed the data collection, provided statistical support, provided the analysis, and contributed to the manuscript preparation. Brown can be reached at janie.brown@curtin.edu.au, with copy to ONFEditor@ons.org. (Submitted November 2017. Accepted January 3, 2018.)

References

Ahern, T., & Gardner, A. (2015). Literature review: An exploration of the role of the Australian breast care nurse in the provision of information and supportive care. Collegian, 22, 99–108.

Ahern, T., Gardner, A., & Courtney, M. (2015). Geographical comparisons of information and support needs of Australian women following the primary treatment of breast cancer: A 10-year replication study. Health Expectations, 18, 2678–2692. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12242

Akechi, T., Okuyama, T., Endo, C., Sagawa, R., Uchida, M., Nakaguchi, T., . . . Furukawa, T.A. (2011). Patient’s perceived need and psychological distress and/or quality of life in ambulatory breast cancer patients in Japan. Psycho-Oncology, 20, 497–505. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1757

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2014). Cancer in Australia: An overview. Retrieved from https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/79c940b1-2438-45c8-99e2-a4b593253ccd/1…

Browall, M., Kenne Sarenmalm, E., Persson, L.O., Wengström, Y., & Gaston-Johansson, F. (2016). Patient-reported stressful events and coping strategies in post-menopausal women with breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care, 25, 324–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12294

Cancer Australia. (2017a). Breast cancer statistics. Retrieved from https://breast-cancer.canceraustralia.gov.au/statistics

Cancer Australia. (2017b). Understanding breast cancer in men. Retrieved from https://canceraustralia.gov.au/about-us/news/understanding-breast-cance…

Çömez, S., & Karayurt, Ö. (2016). We as spouses have experienced a real disaster!: A qualitative study of women with breast cancer and their spouses. Cancer Nursing, 39, E19–E28. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000306

Cordeiro, E., Dixon, M., Coburn, N., & Holloway, C.M. (2015). A patient-centered approach to wait times in the surgical management of breast cancer in the Province of Ontario. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 22, 2509–2516. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-4320-3

Cruickshank, S., Kennedy, C., Lockhart, K., Dosser, I., & Dallas, L. (2008). Specialist breast care nurses for supportive care of women with breast cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, CD005634. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD005634.pub2

Dickerson, S.S., Alqaissi, N., Underhill, M., & Lally, R.M. (2011). Surviving the wait: Defining support while awaiting breast cancer surgery. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67, 1468–1479. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05612.x

Driessnack, M., Sousa, V.D., & Mendes, I.A. (2007). An overview of research designs relevant to nursing: Part 3: Mixed and multiple methods. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 15, 1046–1049.

Eley, R., & Rogers-Clark, C. (2012). Consumer perceptions of the effectiveness of a breast care nurse in providing coordinated care to women with breast cancer. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 29(3), 56–61.

Eley, R.M., Rogers-Clark, C., & Murray, K. (2008). The value of a breast care nurse in supporting rural and remote cancer patients in Queensland. Cancer Nursing, 31, E10–E18. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000339246.60700.cf

Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Dikshit, R., Eser, S., Mathers, C., Rebelo, M., . . . Bray, F. (2015). Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International Journal of Cancer, 136, E359–E386. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29210

Fiszer, C., Dolbeault, S., Sultan, S., & Brédart, A. (2014). Prevalence, intensity, and predictors of the supportive care needs of women diagnosed with breast cancer: A systematic review. Psycho-Oncology, 23, 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3432

Fox, J.P., Philip, E.J., Gross, C.P., Desai, R.A., Killelea, B., & Desai, M.M. (2013). Associations between mental health and surgical outcomes among women undergoing mastectomy for cancer. Breast Journal, 19, 276–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbj.12096

Graneheim, U.H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24, 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

Halkett, G., Arbon, P., Scutter, S., & Borg, M. (2006). The role of the breast care nurse during treatment for early breast cancer: The patient’s perspective. Contemporary Nurse, 23, 46–57. https://doi.org/10.5555/conu.2006.23.1.46

Johnson, B., & Christensen, L.B. (2012). Educational research: Quantitative, qualitative, and mixed approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Luck, L., Chok, H.N., Scott, N., & Wilkes, L. (2017). The role of the breast care nurse in patient and family care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26, 3422–3429. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13704

National Breast Cancer Centre. (2001). Clinical practice guidelines: Management of early breast cancer (2nd ed.). Canberra, Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council. Retrieved from https://canceraustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/cpg-cli…

Philip, E.J., Merluzzi, T.V., Zhang, Z., & Heitzmann, C.A. (2013). Depression and cancer survivorship: Importance of coping self-efficacy in post-treatment survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 987–994. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3088

Polit, D.F., & Beck, C.T. (2017). Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice (9th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health.

Porter-Steele, J., Tjondronegoro, D., Seib, C., Young, L., & Anderson, D. (2017). ‘Not one size fits all’: A brief review of models of care for women with breast cancer in Australia. Cancer Forum, 41, 13–19.

Rottmann, N., Dalton, S.O., Christensen, J., Frederiksen, K., & Johansen, C. (2010). Self-efficacy, adjustment style and well-being in breast cancer patients: A longitudinal study. Quality of Life Research, 19, 827–836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-010-9653-1

Schneider, Z., Whitehead, D., Lobiondo-Wood, G., & Haber, J. (2016). Nursing and midwifery research: Methods and appraisal for evidence-based practice (5th ed.). Sydney, Australia: Elsevier.

Watts, K., Meiser, B., Conlon, H., Rovelli, S., Tiller, K., Zorbas, H., . . . Friedlander, M. (2011). A specialist breast care nurse role for women with metastatic breast cancer: Enhancing supportive care. Oncology Nursing Forum, 38, 627–631. https://doi.org/10.1188/11.ONF.627-631